When we hear the name “Winston Churchill,” images of the cigar chomping, overweight, elderly aristocrat who led England through their Finest Hour probably come to mind. What few people realize, however, is that as a young man Churchill lived a life of romantic adventure and daring by fighting at the battlefront in three different wars before he was 23 years old. And he capped off his military career by serving as a 24-year-old war corespondent in the Boer War, where he was taken prisoner, made an audacious escape, and returned home to England as a national hero.

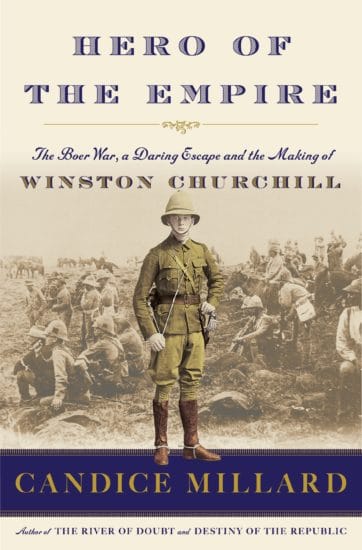

My guest today on the podcast has just published a detailed account of Churchill’s capture and escape during the Boer War and how it launched his career as the statesman we remember today. Her name is Candice Millard, and you may have read her previous book The River of Doubt about Theodore Roosevelt’s exploration of the Amazon. Her latest book is called Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape, and the Making of Winston Churchill.

On today’s show Candice and I discuss the supreme confidence Churchill had as a young man that he was destined for greatness and how he intentionally sought after dangerous military missions that would catapult him to fame. We also discuss the compelling leadership and persuasion ability Churchill displayed during the Boer War that would later propel his political career, as well as the similarities between Churchill and Teddy Roosevelt.

Show Highlights

- The daring military exploits Churchill took part in around the world before he was 24 years old

- Why Churchill loved war so much

- How the Boer War ushered in modern warfare

- The unabashed egoism of Churchill and why he thought he was destined for greatness even as a boy (and what he did to make that happen for himself)

- How Churchill was able to transform himself from a chubby, sensitive boy to a brash, daring, and fit young man

- How Churchill’s sad family life as a boy helped add fuel to the fire of his ambitions

- Churchill’s first run at MP at the age of 24 and how he responded when he lost

- How Churchill became the highest paid reporter in England at the age of 24

- Why Churchill went to the Boer War as a war correspondent and not an officer in the military

- Why and how Churchill was taken as a POW in the Boer War even though he wasn’t a soldier

- How Churchill’s experience as a prisoner influenced the policies in prison reform that he pushed as a member of parliament

- Why people naturally listened to and followed Churchill even when he was only 24 years old and not an officer

- Churchill’s original audacious plan to escape from prison

- Would there have been a Winston Churchill leading England during their finest hour had he not been a POW?

- The similarities between Theodore Roosevelt and Winston Churchill

- And much more!

Resources/Studies/People Mentioned in Podcast

- The River of Doubt

- My podcast with Steve Kemper about American Boer War scout Frederick Russell Burnham

- The Boer War

- The Winston Churchill Guide to Adulthood

- Lord Randolph Churchill

- Lady Randolph Churchill

- Armored trains during the Boer War

The Hero of the Empire is a captivating and insightful read about the makings of one of the West’s greatest statesman. If you want to understand what made Winston Churchill who he came to be, it’s a must read.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Connect With Candice

Tell Candice “Thanks” for being on the podcast via Twitter

Podcast Sponsors

Tecovas. Handmade cowboy boots at half the cost of retail. Check out my go-to cowboy boot, the Cartwright, at tecovasboots.com and get $25 off your first pair of boots by using code MANLINESS at checkout.

Five Four Club. Take the hassle out of shopping for clothes and building a wardrobe. Use promo code “manliness” at checkout to get 50% off your first box of exclusive clothing.

Squarespace. Build a website quickly and easily with Squarespace. Start your free trial today, at Squarespace.com and enter offer code ARTOFMAN to get 10% off your first purchase.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. When we hear the name Winston Churchill images of the cigar chomping, overweight, elderly aristocrat who led England through their finest hour probably come to mind. What few people realize, however is that as a young man Churchill lived a life of romantic adventure and daring by fighting at the battlefront in three different wars before he was 23 years old. He capped off his military career by serving as a 24 year old war correspondent in the Boer War in Southern Africa where he was taken prisoner, made an audacious escape and returned home to England as a national hero.

My guest today on the podcast has just published a detailed account of Churchill’s capture and escape during the Boer War and how it launched his career as the statesman we remember today. Her name is Candice Millard. You’ve probably read her previous book, “The River of Doubt”, about Theodore Roosevelt’s exploration of the Amazon. Her latest book is called, “Hero of the Empire: the Boer War, a Daring Escape and the Making of Winston Churchill. On today’s show Candice and I discussed supreme confidence Churchill had as a young man that he was destined for greatness and how he intentionally sought after dangerous military missions that would catapult him to fame. We also discussed the compelling leadership and persuasion ability Churchill displayed during the Boer War that would later propel his political career, as well as the similarities between Churchill and Teddy Roosevelt. Stay tuned for a fascinating podcast on one of history’s most fascinating figures. After the show check out the show notes at aom.is/millard, that’s spelled M-I-L-L-A-R-D.

All right, Candice Millard, welcome to the show.

Candice Millard: Thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: I’ve long been a fan of your work. I loved your book, “River of Doubt”, about Teddy Roosevelt’s adventure down in uncharted part of the Amazon River. You’ve got a new book out, “Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, Daring Escape and the Making of Winston Churchill”. A lot has been written about Churchill. He’s one of those figures that biographers love to write about, but it’s often about the later parts of his life. What drew you to writing about a younger Churchill’s capture and escape as a prisoner of war in the Boer War?

Candice Millard: Well as you say we all know Winston Churchill. I think there’s something like 12,000 books about him, but a lot of it obviously focuses on his time in World War 2 and his role in it and the fact that he was such an extraordinary leader. What interested me was what made the Winston Churchill we all know. Where did he come from? How did he have this incredible ability and confidence and how was he able to project it to his people and to entire nations? The answer is South Africa.

If you look at it this war not only propelled him to the political stage. He became a national hero during this war because of his escape. He had run for parliament before and lost. He ran again, and on the strength of his popularity he himself says coming out of the South African war won the second time and it launched his political career. More than that you can see him so clearly at this young age with all the qualities we think of him having later in life with his audacity, his determination, his grit, his agility and ingenuity. They all come into play in South Africa.

Brett McKay: Yeah, you’re right, when most people think of Churchill they usually imagine the cigar chomping, overweight, aristocratic statesman leading Great Britain in their finest hour. As a young man, he was 24, 25 during the Boer War, Churchill lived a life of romantic daring that culminated in the Boer Wars. Even before the Boer Wars he had some military escapades. Can you tell us a bit about that and what drove him to put himself in harm’s way like that?

Candice Millard: He had always loved war and been fascinated by it. Even as a child he had 1,500 toy soldiers that he played with. He also was the direct descendant of the first Duke of Marlborough, John Churchill, who is considered to be one of England’s greatest generals. He was very much aware of that legacy. He was born into the highest ranks of the British aristocracy at the height of the British Empire, so he had a lot of wars to choose from. The British Empire ruled over 450,000,000 people at that point, so they were constantly putting down revolts from Egypt to Ireland.

Churchill thought of war as sort of his vehicle to fame and then political power. He called it the glittering gateway to distinction. You’re right, by the time he goes to South Africa he’s 24 years old, but this is his fourth war on three different continents. He went to Cuba right before the beginning skirmishes of the Spanish-American War. He went to British India and fought. He went to the Sudan and fought in the famous Battle of Omdurman. He was a very experienced, seasoned soldier by the time he goes to South Africa.

Brett McKay: I imagine there was something about the culture of Victorian England that compelled him to put himself at the battlefront.

Candice Millard: Right. To England at that time, they didn’t thing really about war, they thought about gallantry. They spend a lot more time sort of working on parades and pressing their uniforms and shining their medals than they did actually thinking about the realities of war, even though they had been in so many of them. Many of them were colonial wars where they had far better weapons and more men and could easily overwhelm their enemies. That turned out to be a serious problem for them in South Africa because they were facing a completely different kind of enemy there.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and we’ll talk about that in a bit. It seems like the Boer War really ushered in modern warfare.

Candice Millard: Yeah, it did. Absolutely. There’s no question it was some of the earliest guerrilla fighting. They even called it the Khaki War because it was one of the first times that the British Army was sort of resentfully convinced to stop wearing their dashing red coats. They hated the khakis. They said it made them look like bus drivers. They were still fighting in these perfect, precise lines, sort of set up for the slaughter. It was also some of the first concentration camps and changing of modernization of weapons. It really prepared the British Army for World War 1.

Brett McKay: We’ve written a lot about Churchill and I’ve read a lot about him. One thing about him is he is an egoist. He’s a self-described egoist. He will cop to that accusation. You talk about this right from the get-go in your book, that from a young age he felt he was destined for greatness. Where did this feeling of certainty that he would be a great man one day come from?

Candice Millard: I think you’re born with it. I think what’s different about Churchill is that he not only believed it, and I think a lot of young people, certainly a lot of young men believe that they’re destined for greatness, that they’re special, that they’re different and they’re going to do something extraordinary, but he didn’t sit around waiting for something to happen to him. He went out and he found his opportunities again and again and again. He threw himself not only into war but into the most brutal battles he could find. He would do these extreme things just to get attention so he would get medals. Then he thought he can turn this into fame and to power.

He, for instance, rode a white pony on the battlefield to the horror of the people around him just to get noticed. As you say he said he had faith in his star. I remember one of my favorite things he wrote to his mother when he was in the middle of a war and he had seen his friends not just killed but slaughtered he said he didn’t think the gods would create so potent a being as himself for so prosaic an ending. He just didn’t think it was going to happen to him because he had this larger life ahead of him.

Brett McKay: Right. One thing he did that was very un-British is he shared with others his premonitions about his greatness.

Candice Millard: He did. Other people around him believed it too, but the funny thing is again and again and again when I was doing research people would say, “I can’t stand that kid Winston Churchill. He drives me crazy. He’s going to be Prime Minister one day, but I just can’t stand him”. He was openly ambitious and that just wasn’t done in the British Military and the British society in which he had been born. I think of it kind of as the American in him, actually the kind of brash pusher, and his mother was American.

Brett McKay: Right. One thing I remember from reading about Churchill, he was sort of a sensitive boy. He was kind of overweight, kind of soft. Even as an older man he liked to wear silk pajamas and he really pampered himself. I can imagine people looking at this sort of aristocrat guy who has kind of a lisp, not super athletic thinking, “Yeah, he’s saying he’s destined for greatness but I don’t know if that’s true”. How was he able to transform himself?

Candice Millard: Well I think that it’s interesting to me, his early life when he was a child because he ends up becoming a writer, an extraordinary writer. That’s how he supported himself for most of his life, and that’s actually how he got to South Africa, as a correspondent. Not only is he sort of not strong physically, but he thinks and is seen as not strong intellectually, which seems incredible to us now. Because he wasn’t a great student they didn’t put him into the Greek and Latin classes which were set aside for the more capable students. They just kind of stuck him in the regular English class, but he had this extraordinary teacher and he came to know the English language inside and out. He had this power actually over other people, which as you know, translated to incredible power. The power of words later on is an incredible weapon, an incredible tool to inspire other people. He had that throughout his life.

As he became a young man he was more fit, and because he had thrown himself into these situations again and again. He was always very, very confident so he believed that he would do fine on the battlefield, and he did.

Brett McKay: Yeah, he did. You mentioned his mother. His mother was American. Churchill had a really interesting family life as a boy and young man. I’m sure it had a huge influence on his ambitions. Can you tell us a bit about his family and his relationship with his parents and how it effected him throughout the rest of his life?

Candice Millard: His father was Lord Randolph Churchill, who had been the Chancellor of the Exchequer and had been leader of the House of Commons, so a very famous and powerful man who was actually very, very hard on his son and didn’t spend much time with him. It was, I think, one of the great regrets of Churchill’s life. He later said that he wished he had been a shopkeeper’s son because he would’ve had a chance to get to know his father, which would’ve been a joy to him.

As it was his parents sent him off to boarding school when he was seven years old. They just never made time for him. His father was very, very busy with his political career and his mother was very busy with her social life. As you say she was this incredibly beautiful American socialite, born Jennie Jerome. When she came to England she became the star, sort of the glittering center. Of course there were people who resented her because of who she was, because she was American for one thing, but she just didn’t care. She loved life, she loved being the center of attention and she was really too busy for him often.

I’m a mother myself and I actually found it really heartbreaking to read his letters home to his parents from boarding school, begging them to visit him, and they just never did. Again and again he would even figure out what trains they could take and what the schedule would be and how they could then quickly get back to London and then they just didn’t take the time. Then Churchill’s father died when he was just 45 years old. He died a very public and tragic death. Then Churchill himself became interesting actually to his mother. He became a young man of consequence. She had all these relationships, she had all this power with very powerful men, all this influence. He told her, he said, “This is a pushing age. We must push with the best, and I want you to get me these military appointments because I want to be able to go anywhere in the world where the most interesting fighting is going on”. She helped him again and again and again.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that was interesting, his mother was very influential in helping his political career. Even she tried to pull strings while he was a prisoner of war as well. You’re right, I’ve read those letters that Churchill wrote when he was in boarding school and it just breaks your heart, it’s super sad.

Candice Millard: Absolutely.

Brett McKay: When Churchill was a young man, I guess he’s about 24, he begins his foray into politics by running for a member of Parliament in Oldham in 1899. He loses. How did someone with so much unbridled ambition like Churchill respond to that defeat?

Candice Millard: Well he was completely disappointed. He felt like he had all this promise and he believed strongly in himself, but it was a different thing to try to convince everybody else. It was difficult to get there. Nothing had worked. He had tried war and he had tried politics and here he was, he had no income, he had been born in Blenheim Palace with all this incredible opulence around him, but they didn’t have any money. Even the people who … He didn’t inherit the title of the palace, but even those who did they were desperately selling of the gems and the library and the art collection just to try to stay afloat. His father had left him very little money. His mother had spent most of it. He needed to find another way, and he believed that he needed another war, he needed another opportunity to prove himself.

When he had heard the rumblings of war happening in South Africa, he saw that as his opportunity.

Brett McKay: Okay, let’s go there. Before we talk about Churchill’s involvement in the Boer War, let’s talk a little about the background of the word for those who aren’t familiar with it. It took place in South Africa. Who were the British fighting exactly during the Boer War?

Candice Millard: The Boers were this group of largely Dutch, Huguenot and German immigrants who had been living in South Africa for centuries. They were very religious. They were unabashedly racist and they were stubbornly independent. Most of all they just wanted to be left alone. They were trying to get away from the British Empire by moving into the interior of Africa. In 1834, just two years after the British Empire had abolished slavery, which was sort of the final straw for the Boers, they took what they called the Great Trek which was moving hundreds of miles from the Cape into the African interior. They established three different republics at that time.

Unfortunately for them they found gold and diamonds, especially in an area called the Transvaal, or the South African Republic, one of their three republics. Paul Kruger, who had become president of the Transvaal said that “this gold will cause our country to be soaked in blood”, and he was right. Just a few years later, in 1880, the first Boer War took place between the British and the Boers. To the British shock they actually lost. It was a very short war, but they lost. The Boers had sort of temporarily had their independence, but I think they both knew that the British weren’t going to forget about it. The area itself was very interesting to the British anyway because obviously they had to get around the Cape to get to India. Then with the gold and diamonds they just weren’t going to let go. It became more and more tense between the two groups.

Brett McKay: Okay. What’s interesting about the Boer War was Europeans fighting Europeans in Africa. Some people have called it like the American Revolution in Africa. A lot of Americans sympathize with the Boers.

Candice Millard: Right, absolutely.

Brett McKay: Churchill goes to South African, but he goes not as a soldier but as a war reporter. For a guy who loved and romanticized battle why not go as an officer in the military?

Candice Millard: He had already left the military and he knew, again he’s trying to make money and this was his ticket to South Africa. He had done this unusual thing when he was taking part in these other wars earlier on. He had been both a combatant and a correspondent. In fact, because he had so openly criticized those who were in command, especially Kirchner, they had had to make a rule that you couldn’t be both. You couldn’t both write about the war and fight in it. He very quickly got offers from all of these newspaper publishers asking him to write for them because he was an incredibly skilled reporter. Not only was he incredibly ambitious and intrepid so wherever something was happening he was the first person there. He was also obviously brilliant. His analysis was incredibly insightful. Most of all his prose was absolutely beautiful.

I read a lot, a lot, a lot of newspaper articles from that time covering this war and without question Winston Churchill’s writing is head and shoulders above everybody else. He was smart, so he has all these offers. He takes it to different people and he’s like, “Look, this newspaper is going to give me this. What will you give me?” In the end he ends up becoming the highest paid correspondent that England had ever had.

Brett McKay: That’s crazy. How much was he paid in today’s dollars?

Candice Millard: He was paid a huge amount. I can’t remember to be honest. It was something like close to $100,000 to cover this war. He also had a huge stipend, so they would cover all of his expenses while he was there. As you were saying earlier he was willing to risk his life and throw himself into these dangerous situations but he didn’t see the point in being uncomfortable or uncivilized while he was there so he brought with him his valet and he also bought all of this alcohol to take with him, so a very nice selection of wines and something like 18 bottles of 10 year old Scotch whiskey to take along and the newspaper paid for it all.

Brett McKay: That’s crazy. What’s amazing too, I think people need to keep in mind, he was only 24 when this happened.

Candice Millard: Right. This is not only his fourth war, he has already written three books and run for parliament, so he’s a little ambitious.

Brett McKay: Right. That makes me feel like a slacker.

Candice Millard: Me too.

Brett McKay: A complete slacker.

Candice Millard: Can’t keep up with this guy.

Brett McKay: Right. How did he become captured as a POW? If he was a journalist you would think that he’s not really a combatant so the laws of war would say you can’t hold him as a prisoner of war. Why did the Boers treat him like a combatant?

Candice Millard: He acted like a combatant, because he’s Winston Churchill and he couldn’t help himself. He gets to this little town called Estcourt, which is as close you can get to the front. The front was in Ladysmith, which was just south of Pretoria. Ladysmith was completely surrounded by the Boers, it’s under siege, you can’t get in or out. The only thing that they have in this campus, they have this armored train that goes out for reconnaissance. Every person in the camp, all these soldiers, all these officers hate this armored train. It seems like, oh that’s a great idea, it would be protective, but it’s a sitting duck. It’s an obvious, easy target for the Boers. They know where it’s going, they know it has to come back on the same tracks.

The men hated it, they called it a death trap, but a friend of Churchill’s, Ulmer Holden, who was in charge of a regiment in Estcourt was ordered to take the armored train out for reconnaissance. He invited Churchill to go with him. Both of them knew that it was just a disastrous decision to take the train out, especially that day. They had just spotted the Boers just outside of Estcourt, just the day before. Holden didn’t have a choice. Churchill had a choice but he was restless, he was frustrated and he would later say that he was eager for trouble. He didn’t hesitate for a minute when Holden invited him along.

He gets on the train and the Boers of course are watching. As soon as it goes past them they got to the bottom of a hill and they pile rocks on the tracks. Then they go to the top of that hill, they wait for the train to come back because they knew it would. As soon as it gets to the top of the hill they have this hailstorm of shells and bullets. The train does exactly what they want it to do, it goes down the hill as fast as it can to try to get away from the attack and it crashes into these rocks at the bottom of the hill. The first two cars are catapulted off the tracks and several men are killed, many are horribly wounded. Winston Churchill, who’s one of the few civilians on the train, and again is only 24 years old, he jumps out and immediately takes charge of the defense.

He’s running back and forth shouting orders, organizing a way for the train to get away. What’s even more extraordinary is that everyone listens to him. There were plenty of legitimate uniformed soldiers on that train. Holden who was in charge, he is too. He’s also listening to Churchill, he’s taking command and he lets him have at it. Churchill succeeds, the train finally has to shove one of the cars off the tracks. He figures out a way to do that and it gets away. Every man who survives, who gets out alive without being killed or captured credits the saving of his life to Winston Churchill.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that’s crazy. The Boers capture him because he’s acting as a combatant, but I guess you also mention in the book that they were keen on keeping him because I guess his father had kind of rubbed them in the wrong way and they wanted to hold onto this guy because he’s the son of the guy that kind of did us wrong.

Candice Millard: Right. They are thrilled to have Winston Churchill because one, he’s the son of a Lord who represents everything that they hate about the British, their arrogance and their aristocracy. Also, as you say, Randolph Churchill had been there just a few years earlier and had written letters home that were published in British newspapers excoriating the Boers for their backwardness, for not being educated, but mostly for their treatment of native Africans, which was absolutely true, but it didn’t make them hate him any less.

Brett McKay: He got captured as a prisoner but the way you described it doesn’t seem like the conditions were that bad. It seemed like Churchill was able to wander the streets. He was able to buy stuff, hats, clothing, liquor, he made friends with the minister of war for the Boers or something like that. What were the conditions like?

Candice Millard: He wasn’t able to leave but they were incredibly comfortable. The Boers really hated the thought that the British thought that they were these backward bafoons and so they went out of their way to show that they were very civilized. This was a prison just for officers. As you say, he was able to have a barber come in and cut his hair. He was able to order a tweet suit. They got the newspapers in. When it was hot they let them sleep in the hallways instead of in their rooms. They had sort of this comfortable life, but for Churchill it was absolutely unbearable. From the minute he was captured he was determined to win his release, whether it was arguing he wasn’t a combatant, they weren’t listening to that because they obviously had seen it and they had read the newspaper accounts from the other men who had been on the train praising Churchill, or through escape.

He would write about it. He would remember how it felt to be a prisoner for the rest of his life. He would say that his captivity, he hated more than he had ever hated any period in his whole life. He would remember it. Later on in life when he came to power when he was a home secretary he made a point of making sure that prisoners had access to books, had access to the outdoors and to exercise because he remembered it as just being this unbearable situation.

Brett McKay: Churchill had to get out there. He had to start making plans when his channels of trying to talk his way out didn’t come to fruition. His original plans, in typical Churchillian fashion, he came up with this really grandiose and complicated plan. People were like, “Yeah, let’s do that”, but there was a certain point when they were like, “No, that’s actually not a good idea”. Can you talk a little bit about Churchill’s original plan to escape?

Candice Millard: Again, this is Winston Churchill so he’s not going to just have some quiet little plan where just he escapes. No, he wants to take over the entire prison and then take over the prison where the soldiers are kept and then take over Pretoria and kidnap the president and end the war. It’s this really, really elaborate, grandiose plan. Everybody’s like, that’s not going to work, that’s ridiculous. They kind of shoo him away.

He overhears his friend Ulmer Holden, who’s the guy who had invited him to get on the train at the beginning, and this other guy, Adam Brocky, who was a really interesting guy who had been in South Africa for quite a while, knew the train really well and actually spoke Zulu and Afrikaans. He overhears them talking about a plan of their own and he wants in.

Brett McKay: Yeah. They decide to make this plan. The three of them are going to escape together, but it didn’t work out that way. Churchill ended up being alone. He had to get back to, I forget where it was, he had to travel a couple hundred miles to get to safety. The area was teeming with Boers. How did he make that escape? Was it just primarily luck or was there skill and savvy involved?

Candice Millard: As you say he is able to … Their plan is there’s this six and a half foot tall fence surrounding the prison yard and there are armed guards everywhere, but they see that at night when the electric lights come on there’s one corner of the yard that’s still dark. They think that if a guard is turned at just the right moment they can quickly get over. Brocky and Holden had tried and were giving up for the night. Churchill gave it one more try and got over. Holden and Brocky couldn’t join him.

The problem was that they had all the provisions. Churchill found himself on the other side. He couldn’t get back in, he would be shot. He was on the other side of the fence with no map, no compass, no food, no weapon, he doesn’t speak the language. The Boers, when they find out are humiliated and enraged that anyone would escape, but especially that it would be Winston Churchill. They are determined to catch him.

He has ahead of him almost 300 miles of enemy territory. He’s trying to get to what’s now Mozambique, was in Portuguese East Africa. A lot of it is luck. He fluctuates between this easy confidence and despair. It’s really just an extraordinary story of survival. It really is incredible that he did come out alive.

Brett McKay: Right. We won’t get into details of his lucky breaks that he got, save that for the book. Churchill indeed had a star shining upon him. He returns to England and he’s a hero, a national hero. If there wasn’t a Boer War and there wasn’t an escape from this prison would there have been a Churchill that lead Britain during their finest hour?

Candice Millard: Absolutely. I think that he would’ve found a way no matter what. He never gave up, he never stopped and that’s what made him so valuable during World War 2. That is what was going to propel him to the forefront of the national stage no matter what. This was a faster and a more exciting way to get there, and it makes for a really incredible story, and it was a pivot point in his life. He would later say “this misfortune”, you know his capture, “had I known it, was to lay the foundation for my later life”, and it absolutely did. There’s no question in my mind at least that he would’ve found a way there somehow.

Brett McKay: Somehow. We mentioned earlier, Candice, that your previous book was about Theodore Roosevelt, his adventure down the river of doubt in the Amazon. Churchill and Roosevelt lived in about the same time period, some of that same era. As you were writing about Churchill, did you find similarities that existed between him and Roosevelt?

Candice Millard: Constantly. I was constantly stunned by how much they were alike. They were both such incredibly ambitious and arrogant men. They were both incredibly well read. They were both extraordinary writers. They were both born leaders. It’s interesting to study people like this because I really believe that to be a great leader you have to be born a great leader. I think like any other skill, you can learn it to some limited extent. I don’t think that you can be a Winston Churchill or a Theodore Roosevelt if you’re not just born that way.

It was really interesting to me just to quickly go back to the attack on the armored train. As he’s giving orders there comes a moment when the train driver jumps out of his cab and he’s been hit by a fragment of a shell and he’s bleeding and he’s furious and he looks at Churchill and he says, “They don’t pay me enough for this, I’m not a member of the military”, and he’s going to make a run for it. Churchill realizes that if he does then they have no hope because nobody else can drive the train. He immediately gives him this sort of mini Saint Crispin’s Day speech. “Look this isn’t a terrible thing this has happened to you. On the contrary, this is an extraordinary and rare opportunity. You can prove your gallantry. You can prove your bravery and your devotion to your country if you get back in that cab. If you do, I will make sure that you’re acknowledged for it”. The guy looks at him and says, “Okay”, and he does.

He turns around and he gets back in the cab and he does everything Churchill says. Churchill is 24 and Churchill is not even a member of the military. Not only was he himself deeply confident, but it was something that was contagious. He could transfer that to whomever he was talking to or entire nations. If he believed in you, if he believed that you were brave, you were resourceful, that you were extraordinary and you could do extraordinary things, you believed it too and you were capable of it.

Brett McKay: Candice, this has been a great conversation. Where can people learn more about your book?

Candice Millard: Thank you very much. They can go to my website, candicemillard.com or they can just pick up a book anywhere.

Brett McKay: Awesome. Candice Millard, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Candice Millard: I really enjoyed it. Thank you very much.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Candice Millard. She’s the author of the book “Hero of the Empires”, available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about her work at candicemillard.com. Also, check out the show notes at aom.is/millard, that’s M-I-L-L-A-R-D.

Well that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. Our show is edited by Creative Audio Lab here in Tulsa, Oklahoma. If you have any audio editing needs or music production needs there’s a place to go. You find that at creativeaudiolab.com. If you’ve enjoyed this show and have got something out of it, I’d appreciate if you’d give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, helps us out a lot.

As always, thank you for your continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.

Tags: Winston Churchill