When Odysseus was a young man, the legend holds, he visited his grandfather Autolycus, who had named the future hero as a baby. Odysseus feasts with his grandfather and a group of uncles and then joins them for a hunt on the wooded slopes of Mount Parnassus. When the men and dogs flush a giant boar from his lair, Odysseus, though he is the youngest in the group, is the first to lunge for the beast with his spear. But the animal dodges the blow and gores the brave lad above his knee. Undeterred, Odysseus rebounds and runs his weapon through the boar, slaying it. His uncles take care of the carcass, bind the young man’s deep gash, and bring him back to Autolycus’ home to heal. After Odysseus recuperates, he returns to Ithaca with a new scar, and a new story; when his parents ask him how he got the wound, he recounts with pride the way in which he held his own in a group of men.

It’s a rite of passage for Odysseus — his first big hunt and chance to test his courage and learn the skills and male cooperation essential for success in battle. The episode also ends up playing a role in a much different homecoming decades later.

When Odysseus returns as an older man to Ithaca after 20 years of epic fighting and wandering, he initially keeps his true identity as king a secret. Disguised as a beggar, he plots to kill the suitors who have tried to usurp his position while he’s been away, and works to discern whether his wife Penelope has remained faithful. After telling her he’s crossed paths with Odysseus, and sharing information about his journey, Penelope so appreciates his tales that she asks his childhood nurse, Eurycleia, to wash his feet.

As the still-disguised king places his bare legs into a pot of water and Eurycleia begins to bathe them, she immediately recognizes his old hunting scar and knows who sits before her. The aged nurse’s eyes fill with tears and she exclaims to her former charge: “My dear child, I am sure you must be Odysseus himself, only I did not know you till I had actually touched and handled you.”

As one classicist has observed, “While the scar proves Odysseus’ identity…the episode that produced the scar helped to establish that identity in the first place.”

In other words, gaining the scar helped make Odysseus into a man; and forever after, it marked him as one.

Physical scars have held a long and interesting place in the history and anthropology of masculinity. Scars that resulted from being branded as punishment for a crime could be ostracizing; and ones left from being whipped as a slave were emasculating. But scars earned on the hunt, in battle, and in pursuing various adventures were, and are, often seen as marks of honor and a source of both public and personal pride. Today we’ll offer a few snapshots of how men have viewed their scars through time and around the world.

Scars as Tokens of Initiation

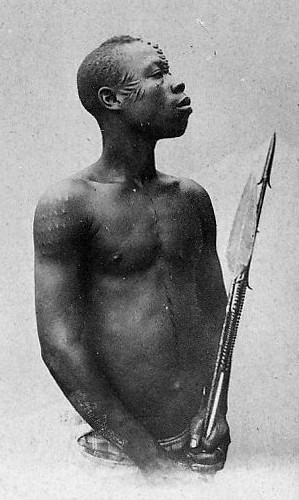

Intentional scarification has been practiced in many cultures around the world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and Australia. Scars were in some ways the equivalent of tattoos for these peoples, as darker skin is more difficult to ink, but more prone to producing visible, pronounced, keloid scars.

Scars were carved into the skin with shells, flints, or sharpened sticks, and could take various forms. The wounds were sometimes rubbed with ash, lime, the down of birds, or the fur of a hunted animal to add color, and to irritate the wound so it would form a more pronounced scar. The particular design of the scar could denote a man or woman’s social and marital status, lineage, and membership in a particular tribe or clan. The scar was a visible symbol of who you were and the people to which you belonged. In fact, when a warrior captured a member of an enemy tribe, he would sometimes superimpose the symbol of his clan onto the scar of the prisoner which symbolized his. The message was clear, and to a man whose lineage was his whole identity, devastating: You’re ours now.

Scars were often given as part of a young man’s initiation into manhood. Enduring the pain of the process without crying out demonstrated courage and self-discipline — qualities necessary to becoming an effective hunter and warrior. A young man who had already experienced the feeling of his flesh being torn and pierced — and endured it well — would be less likely to fear the tip of an enemy’s spear or the tusk of an animal.

For a fascinating look at a scarification ritual, watch this video of the Papua New Guinea receiving their “crocodile teeth” to become men.

A 19th century observer of a tribe in South Australia described one such ritual, noting that it followed giving the men a new name, and acted as the finale of their coming-of-age ceremony:

“Everything being prepared, several men open veins in their lower arms, while the young men are raised to swallow the first drops of the blood: they are then directed to kneel on their hands and knees, so as to give a horizontal position to their backs, which are covered all over with blood: as soon as this is sufficiently coagulated, one person marks with his thumb the places in the blood, where the incisions are to be made, namely, one in the middle of the neck, and two rows from the shoulders down to the hips, at intervals of about a third of an inch between each cut. These are named Manka, and are ever after held in such veneration, that it would be deemed a great profanation to allude to them in the presence of women. Each incision requires several cuts with the blunt chips of quartz to make them deep enough, and is then carefully drawn apart; yet the poor fellows do not shrink, or utter a sound.”

While the scar a young man received when he was initiated into manhood was significant, it was only a foretoken — a symbol that he was ready and capable of earning a set of even higher marks: spontaneous scars won in the course of fulfilling his foremost roles as hunter and fighter. These were the scars in which men in cultures around the world took the most pride.

Scars as Badges of Honor

Anciently, honor was seen not as an inner virtue, but as a reputation worthy of respect and admiration. A man’s claim to honor was judged by his peers, and thus his actions, and the visible proofs of such, were highly valued.

At its most basic, manly honor was predicated on strength, toughness, and courage, as well as the readiness to stand up to an insult or attack. A man had to show that if someone hit him, he’d hit back. The resulting showdown often took place not in the heat of the moment, but in arranged duels or rounds of single combat.

The Amazonian Yanomamo provide an evocative example of how this played out at the primitive level. If a Yanomamo man felt another had seriously slandered him, stolen his tobacco or food, or tried to seduce or abduct his wife, the insult would be redressed via a club fight. Two men would square off, and one would allow the other to deliver the first blow. The initiator would arc the end of his club all the way from the ground, through the air, and onto the top of his opponent’s head. The recipient of the wallop was tasked with bearing the blow stoically, without moving or falling over. As anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon reports, the recipient, now with “large chunks of their scalp bashed loose, flapping up and down on their crania,” would then get to deliver a counter blow to his opponent. Whoever remained standing the longest, was the victor.

As a result of these brutal duels, Chagnon observed that “many accomplished and persistent club fighters have scalps that are crisscrossed with as many as a dozen huge, protuberant, lumpy scars two or three inches long after their scalps are healed.” And they’re quite proud of this disfigurement:

“Men with numerous club-fighting scars like these are not bashful about displaying them prominently. They shave the tops of their heads in a tonsure and then rub red pigment into their numerous deep scars, to exaggerate them. Such a man, if he lowers his face and head to you, is usually not showing deference: he is conspicuously advertising his fierceness.”

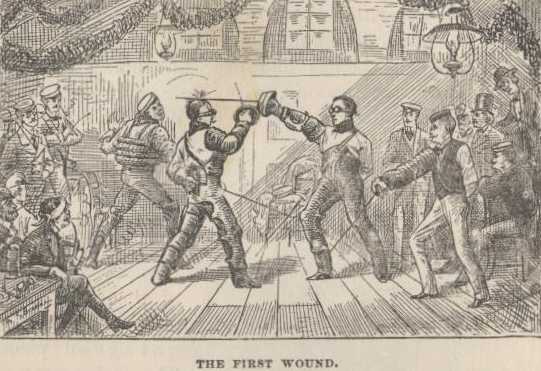

Though duels took a different, more formalized form in Western culture, the very same dynamic of honor — and pride in the scars that resulted in defending it — was very much a part of the culture of manhood in both Europe and America. The currency of dueling scars was particularly high amongst Prussian and Austrian youths in the 19th and 20th centuries. For these young men, sporting a visible dueling scar was honorable and gentlemanly, and not having one was a point of shame.

Prussian students liked to walk around in public sporting the bandages that covered their dueling wounds.

Duels were particularly common amongst Prussian university students, who couldn’t be fully initiated into the school’s fraternities before participating in one, and earning a resultant scar. The affairs were a frequent source of amusement, and considered a good-natured test of skill rather than a deathly serious encounter. The object for a participant was in fact not to kill his opponent (though fatal accidents did occur), but simply to cut him on the face. Students ended up with cheeks criss-crossed with scars, lined foreheads, split noses, and ears sliced off at the tips. Such marks were not felt to mar one’s handsomeness, but to add to it; as a man’s scars were a source of pride, the more visible and pronounced they were, the better. Theology students, on the other hand, preferred to duel with pistols; though this increased the danger, it wasn’t befitting for a future man of the cloth to sport a mincemeat mug.

As anthropologist David D. Gilmore reports in Manhood in the Making, no matter the culture in which duels were fought–

“What seems to matter most is not winning the fight necessarily, although that counts, but rather the readiness to engage or to respond to challenge and the show of indifference to pain. A real man cares nothing about personal injury, laughing at the sign of his own blood. In fighting, win or lose, if he acquits himself bravely in the heat of combat, a man corroborates his claim to manhood, simultaneously bolstering his group’s reputation for strength. An honorable defeat is not itself a loss of face; what seems to matter most is to show a willingness to receive blows, to shed blood. Bruises and scars only add to a man’s prestige and that of his lineage.”

A man’s scars not only demonstrated his gameness for combat, but also worked to bolster his identity as a leader in other capacities as well.

Scars as Marks of Authority, Credibility, and Respect

According to the ancient historian Arrian, when the troops of Alexander the Great mutinied against him in 324 BC, he sought to rally their support with a speech in which he pointed to his scars as tangible evidence of the legitimacy of his leadership:

“Which of you is conscious that he has labored more for me than I did for him? Come now! Whoever of you has wounds, let him strip and show them, and I will show mine in turn; for there is no part of my body, in front at any rate, remaining free from wounds; nor is there any kind of weapon used either for close combat or for hurling at the enemy, the traces of which I do not bear on my person. For I have been wounded with the sword in close fight, I have been shot with arrows, and I have been struck with missiles projected from engines of war; and though oftentimes I have been hit with stones and bolts of wood for the sake of your lives, your glory, and your wealth, I am still leading you as conquerors over all the land and sea, all rivers, mountains, and plains.”

Alexander’s message to his men was clear: I have not asked you to do anything I haven’t been willing to do myself; and here are the scars to prove it.

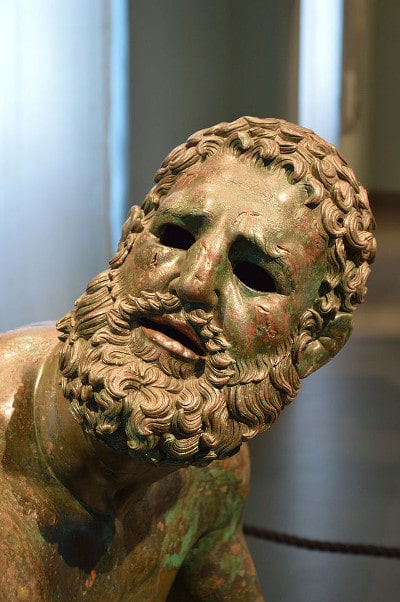

Before Alexander, ancient Greek culture had been somewhat wary of any disabilities or disfigurements, including scars, that marred one’s outer beauty — which was thought to be a reflection of inner beauty. But the epic conqueror’s unabashedly battered body transformed war wounds into an unfettered source of pride.

Yet it would be the Romans who would take the practice of boasting about one’s scars off the battlefield and into the halls of government — elevating the practice into an irrefutable means of establishing ethos and a rhetorical showstopper.

For the Romans, the most important quality of manhood was virtus — or martial courage. As members of an honor culture, each man wished to excel his peers in this quality, and his reputation for it had to be earned through visible, concrete deeds. Exposing oneself to risk on the battlefield — in actions that went above and beyond the call of duty — displayed a man’s virtus. This was particularly true of engaging in hand-to-hand combat; it was thought braver and more honorable to fight an enemy mano-o-mano, than to shoot him from afar with an arrow or impale him with a javelin while mounted on horseback.

Close combat situations were also more likely to earn a man a nice set of scars, which Plutarch called “inscribed images of excellence and manly virtue.” A Roman’s battle-won scars were marks of honor that signaled his status as a man. To have smooth, unmarred skin was shameful, as it signified overweening caution and cowardice. Scars on a man’s back were equally disgraceful — there was nothing laudable about being wounded while running away.

Scars not only earned a man an honorable reputation amongst his fellow soldiers, but carried over into public life as well. Opening your tunic to reveal your scars was an effective way of bolstering your authority and credibility while running for office or arguing with a debate opponent. Scars provided definitive proof of a man’s virtus, and as such were often contrasted with the emptiness of mere talk.

For example, when Lucius Aemilius Paullus returned victorious from war against the Macedonians, the senate moved to vote to declare a “triumph” for him — an official public celebration and sanctification of a military commander’s victory. But Paullus’ troops were unhappy because their general had enforced strict discipline during the campaign, and hadn’t given them as much booty as they thought they deserved. Servius Sulpicius Galba, a military tribune whose service has been undistinguished and who had a personal grievance against Paullus, took advantage of this discontent and went amongst the men to encourage them to oppose the vote.

Marcus Servilius, a war hero, spoke up in front of the assembly in defense of Paullus, and against the scurrilous proceedings. He told the troops that in turning on the man who had led them to victory they insulted their former commander and shamed themselves. He then sought to sway the audience away from Galba, and to himself, by first articulating, and then revealing, his manly bonafides:

“Listen to the decree of the senate, rather than to the romancing of Servius Galba. Listen to this that I am saying, rather than to him. He has learnt nothing but speech-making, and that only to insult and calumniate. I have fought three-and-twenty times in answer to challenges; from all whom I encountered I carried off the spoils. My body is covered with honorable scars, every one received in front.”

At this point, Servilius stripped off his tunic, and explained which battles led to each of his scars. He then finished his defense by saying:

“As an old soldier I have often shown this body of mine, hacked with the sword, to the young ones. Let Galba strip and show his smooth skin with not a scar upon it. Tribunes, call back, if you please, the tribes to vote.”

Men from non-aristocratic families were even more motivated than their elite peers to perform brave deeds in battle, as gaining a reputation for virtus could help them win office and join Rome’s political class. In the absence of a storied lineage, a man could gain support by appealing to his valor; if said valor was engraved on this body, all the better.

Thus when Gaius Marius, the son of a plebian farmer, made an underdog run for the office of consul, he staked his qualifications on the authentic virtue he had cultivated and the respect he had earned as a military commander who had continually shown himself willing to share in the same hardships as his men:

“Compare me now, fellow citizens, a ‘new man,’ with those haughty nobles. What they know from hearsay and reading, I have either seen with my own eyes or done with my own hands. What they have learned from books I have learned by service in the field; think now for yourselves whether words or deeds are worth more…

I cannot, to justify your confidence, display family portraits or the triumphs and consulships of my forefathers; but if occasion requires, I can show spears, a banner, trappings and other military prizes, as well as scars on my breast. These are my portraits, these my patent of nobility, not left me by inheritance as theirs were, but won by my own innumerable efforts and perils.”

The common practice of exhibiting one’s scars to bolster credibility could even be turned on its head in comic, but rhetorically potent ways. When Cicero was prosecuting Gaius Verres, the corrupt, decadent former governor of Sicily, he recalled a prior case when a man was let off for his crimes when his lawyer tore open the defendant’s robe and exposed his numerous scars to the judges and gathered audience. Cicero then wryly asked if Verres’ chest would likewise be bared, “that the Roman people may see his scars, inflicted by the bites of women — the traces of lust and luxury.”

Making an appeal based on one’s scars was also done by the common men of Roman society. For example, in 495 the consul Appius Claudius started handing down harsh sentences to debtors, putting them in bondage to their creditors. When this punishment was given to a group of soldiers, they took their grievances to the consul Servilius and presented him with their scars; he agreed to intervene.

Such a display basically said this: “I have been in the arena; I have fought for the Republic; I too, am a man. Treat me as such.”

Scars as Mementos of Adventures Taken

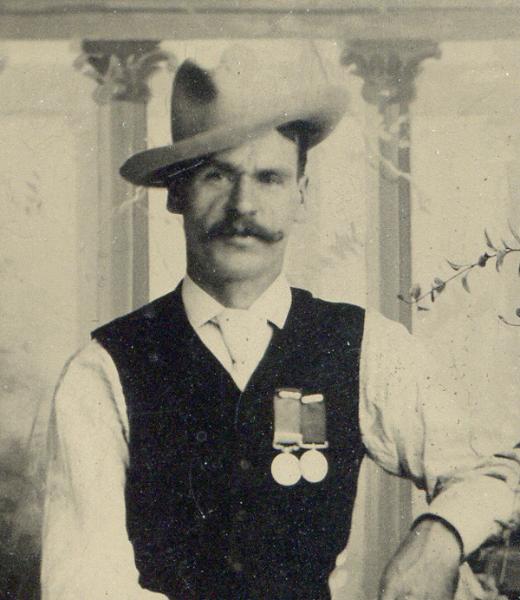

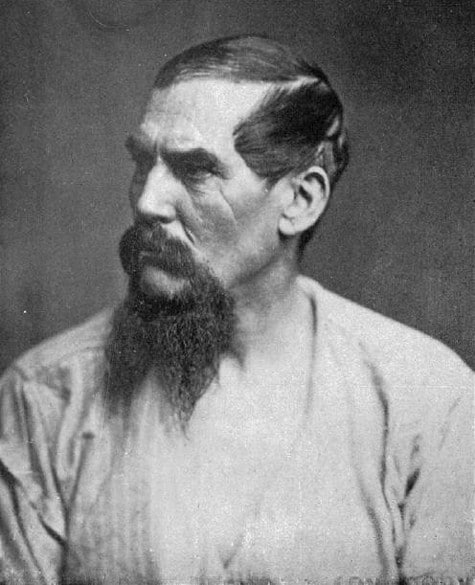

Writer and explorer Richard Francis Burton got this scar while on an expedition in Africa; he was speared in the cheek by a Somali tribesman.

“I am going to my Father’s, and though with great difficulty I have got hither, yet now I do not repent me of all the trouble I have been at to arrive where I am. My sword I give to him that shall succeed me in my pilgrimage, and my courage and skill to him that can get it. My marks and scars I carry with me, to be a witness for me that I have fought His battles who now will be my rewarder.” –The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan (after receiving notice of Theodore Roosevelt’s death, the secretary of his graduating class at Harvard sent out this excerpt to his classmates)

Men earned scars in endeavors other than combat, of course. Scars accrued in the course of dangerous work and risky journeys of many kinds. Such scars became a kind of epidermal relief map, denoting where a man had traveled and what he had done along the way.

As a group, perhaps none carried more such marks than sailors. Ships were full of moving parts, to be managed on an ever-shifting deck. And if the work didn’t scar them, the long journeys provided plenty of chances for breaking the monotony by getting in fights — good-natured or otherwise. Small wonder that a registry of sailors made in the 16th century, which noted significant scars for identification purposes, shows that over half the seamen of the time bore such marks.

Ship owners and captains not only looked to scars to identify their crew members, but seamen used them to read and feel each other out. The number, location, and nature of a sailor’s scars told his mates who were the nautical veterans, who were the defiant troublemakers, and who’d been whipped for mutiny. Scars could thus communicate varying things — that a man was not to be messed with, or that he likely had sage wisdom and was someone to ask counsel from. The marks thus had to be read in the context of other traits of personality and appearance.

Hemingway got this scar when he pulled a skylight down on his head, thinking it was a toilet chain. Because it wasn’t the result of a daring, virile deed, as most of his other scars were, he was reluctant to talk about it.

When it comes to individual men, few embody the nature of adventuresome scars like Ernest Hemingway. As a young man he injured himself in boyhood romps and high school football games; as an ambulance driver and war correspondent he was wounded by mortar shells and machine gun fire; as a traveler he suffered through two plane crashes and three serious car accidents; and as a sportsman he garnered bruises, gashes, and broken bones in boxing matches, bullfighting bouts, safari hunts, and deep sea fishing expeditions. All told, he was wounded hundreds of times, and his body became criss-crossed with scars from the tip of his heels to the crown of his head. His skin became a canvas upon which action and adventure were writ large. And he was quite proud of this “art.”

Wounds and scars unsurprisingly found their way into much of Hemingway’s literary art. The heroes of his books often value self-control, courage, endurance, and love, and they frequently incur scars as part of a kind of initiation into deeper relationships with these dimensions of life. Think of the crusty fisherman Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea, whose “hands have the deep creased scars from handling heavy fish on the cords. But none of these scars were fresh. They were as old as erosions in a fishless desert.” Santiago’s scars foretell the discipline and endurance he will be capable of demonstrating when the wounds of his hands open once more during his epic battle against the marlin; he has been there before, and can do it again.

The honorable connotations of scars began to diminish at the same time that an honor culture as a whole began to unravel: in the aftermath of WWI. The meaning of war wounds became intertwined with the debate over the meaning and value of war itself.

Yet Hemingway also embodies the development of the 20th century’s more complicated relationship with scars. His own physical wounds, as well as those of his characters, often went below the surface to affect the psyche. As a member of the “Lost Generation” he was both fascinated by, and disillusioned with war, and interested in the way it could leave behind hidden scars of emotional trauma.

One can see this tension in The Sun Also Rises. Count Mippipopolous is a veteran of seven wars and four revolutions, and has the scars to prove it. Steady and well-balanced in character, because he’s experienced the crucible of combat and lived life to the hilt, he’s able to relish his indulgences and “enjoy everything so well.” Yet for the book’s protagonist, Jake Barnes, his war wound seems to have crippled his life, rather than enhanced it. He is plagued by an injury that has left him impotent and insecure about his masculinity. His war experiences have unmoored him, and he drifts and drinks through an aimless existence, punctuated by bouts of cruel behavior.

The story bespoke a wider cultural trend in the West; rather than seeing physical scars as the outward tokens of inner strength, they became external signs of psychic distress. Rather than eliciting respect and trust, they began to garner pity and unease.

Scars in the Smooth-Skinned Modern Day

“I just don’t want to die without a few scars… It’s nothing anymore to have a beautiful stock body. You see those cars that are completely stock cherry, right out of a dealer’s showroom in 1955, I always think, what a waste.” –Fight Club

In the present age, men continue to enjoy trading stories about their scars among themselves. But the wider public’s perception of scars can be seen as a continuation of the tension illuminated by Hemingway. A man’s scar still has the ability to elicit some respect and intrigue, but we’re also more apt than ever to wonder if a psychical wound denotes a psychic one. Our increased awareness of PTSD, though needed and well-intended, has had the unfortunate side effect of creating the perception that all soldiers are potential basket cases who might go off at any time.

And of course in some instances, the physical wound and the psychic wound are one in the same; soldiers are increasingly coming home with traumatic brain injuries. These scars make the traditional display and recognition of scars far more complex; neither the veteran nor the public can see them, and both parties can find it difficult to grapple with their meaning.

Our culture’s skittishness with scars hasn’t been helped by the fact that the distance between the general population and the military — or really any dangerous work at all — has never been wider. In the modern age, most men labor and live in such a frictionless world that it’s easy to go through life without accruing any major scars. At the worst, we risk getting a paper cut at work, or slicing a finger in cutting open the plastic wrap around our store-bought meat.

I’ve got a very small scar on my chin from falling on a Christmas ornament as a boy, and a burn on my hand from touching a hot lawnmower as a grown man. And that’s about it. Had I been an ancient Roman, my smooth skin would have been cause for public embarrassment.

It all makes me wonder if the popularity of tattoos in Western culture has at least a little something to do with their being a stand-in for the earning of spontaneous scars. Tattoos throughout history were largely a matter of memorializing actions taken, or a prelude to future deeds. Or they identified a man with a people who he would risk his flesh for. Spontaneous scars were a substitute for the need for such tats (as in ancient Rome), or an accompaniment to them (as in many tribal cultures).

Today, tattoos most often act neither as marks of past actions or as promises of future ones. Of course, sometimes tattoos do memorialize real events. Often, though, we’ve never crawled under barbed wire, but we’ve got it wrapped around our bicep; we’ve never seen a tiger, but we’ve got one on our back; we’re not part of any tribe, but we’ve got tribal symbols on our chest. Without battles and dangerous adventures to mark our skin with wounds showing where we’ve been, and what we’ve done, we paint on symbols of what we’d like to have done, and how we’d like to see ourselves. While scars used to identify us to others, we now use tattoos to identify ourselves, to ourselves.

There are of course still guys out there who have some cool scars, that have been garnered in interesting ways, and constitute well-earned badges of honor and adventure. If you’ve got one, share your story (and a pic!) with us in the comments below!