Roman gladiators occupy a special place in the minds and imaginations of modern men. The imagery of the man in the arena spans millennia, reaching from Ancient Rome itself to the 20th century and beyond. In his famous speech Citizenship in a Republic, Theodore Roosevelt spoke of that man…a man whose face was “marred by dust and sweat and blood” and who will never share his place with “those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.” The image is striking. But who were the gladiators of Rome, really?

The gladiator in ancient Rome was a paradox of sorts. Most were criminals and slaves who could not even feed themselves, and yet, through talented swordplay and a knack for survival, they could attain great fame in the arena. Indeed, even Rome herself was a paradox. The city was the center of the world, the height of civilization, and yet Roman culture often manifested itself in quite a bloodthirsty and barbaric manner, gladiatorial combat being the prime example. Let’s take a look at the men in the arena and see who they were and what their lives were like.

Origins of the Games

The gladiatorial games as we know them originated out of earlier Roman funeral customs. Starting in the 3rd century BC, Roman warriors were believed to have been honored after their death through the sacrifice of prisoners of war. Eventually, the practice morphed from simply sacrificing prisoners of war to having them engage each other in mortal combat. Over time, the practice took hold in society outside the military as well. Gladiatorial matches to honor the dead became so common, in fact, that it was not unusual for wealthy men to set aside funding for the games that would commemorate their own passing. Known as bustiarri (funeral men), these early gladiators not only entertained the crowds, but brought notoriety and honor to the families of the men at whose funerals they performed their deadly art. As many an emperor would later realize, the Roman mob loved the thrill of combat, and the popularity an aspiring politician could obtain through sponsoring games made the gladiators worth their weight in gold.

As the popularity of these funeral games increased, this form of ritual in time grew into common entertainment. By the 1st century BC, gladiatorial games had become big business across the Roman Empire. At the peak of the gladiatorial era, even Emperors themselves sponsored matches featuring hundreds of gladiators competing in extravagant games lasting weeks at a time.

The Men Beneath the Armor

Gladiatorial ranks were filled mainly through the capture of prisoners of war, though many were also criminals from Rome itself. All, save a fortunate few, were considered slaves. There are documented cases of free men volunteering for the games, however. Some were simply desperate men looking for direction, while others sought adventure. All shared the common desire for wealth or freedom, and though the potential for great reward did exist for the gladiator, the only guarantee in such a lifestyle was bloodshed.

Whether the gladiators were slaves or volunteers, the men prepared for the games by undergoing grueling athletic and combat training in schools that were often run by successful retired gladiators. The owners of enslaved gladiators leased their fighters to the schools, criminals were condemned to enroll in one, and volunteers had to obtain permission from a magistrate to join their ranks.

As you can imagine, the more successful a gladiator was in the arena, the more popular he became among the masses. This, in turn, made the gladiator all the more valuable. A proven fighter, particularly if returning from retirement, could earn a considerable sum of money from a single event. Moreover, the most entertaining and courageous gladiators could even hope for rewards from the Emperor. Spiculus, a gladiator under the rule of the Emperor Nero, was gifted with lands and riches equivalent to those given to generals returning triumphant from battle by Nero himself. For prisoners of war or condemned criminals, the most valuable reward was emancipation from their sentence.

Variations of Gladiators and Games

Modern perceptions of gladiatorial combat are often drastically oversimplified. We imagine two men in the arena, bashing at each other with swords until one bests the other with a mortal blow. The movie Gladiator likely expanded many people’s notions of gladiatorial combat to include staged group battles and other formats. In reality, there were countless variations of gladiatorial combat. Historical reenactments of great battles from Rome’s history were common, but these were typically carried out by lesser trained slaves who could not put on as good a show as the more highly skilled combatants. Well-trained fighters often took on a character role, ironically similar to today’s entertainment wrestling organizations, and each role would play a critical part in the show. Let’s take a look at some of the more prominent “roles.”

Retiarius – Considered an inferior class of gladiator, the retiarius was based on the look of a fisherman and was equipped with a net, a trident, and a knife. Armored sparsely for mobility, they did not even wear a helmet and used their mobility and unimpeded vision to trap their opponent with their net and then spear them to death.

Myrmillonis – Known as the “fish men,” these gladiators were almost always matched up against the retiarius. Their armor was often stylized with fish-like characteristics such as scales and fins, and they often carried a large shield and short sword.

Secutor – A pursuit fighter, these gladiators thrilled the mob as they chased their opponents around the arena. The secutor was essentially a more respectable version of the myrmillonis, and also wore stylized armor symbolic of fish. The Emperor Commodus (161-192AD), known for himself participating in the games, fought as a secutor.

Gallus – Heavily armed gladiators who relied on strong defenses and brute force as opposed to speed and agility. These combatants took their name from the formidable warriors of Gaul, and often fought with the traditional gladiator’s sword (gladius) or possibly a lance.

Bestiarii – Technically not gladiators, these combatants fought against animals. The forerunners of modern bullfighters, they would square up against leopards, lions, and other formidable opponents from Mother Nature’s starting lineup.

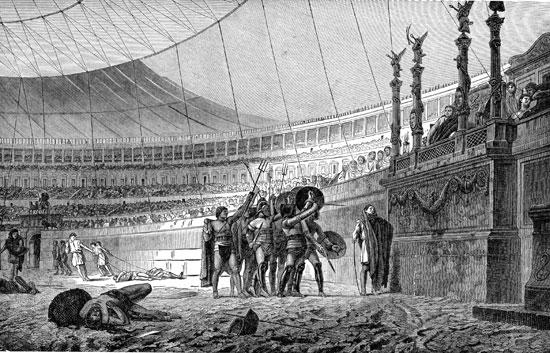

Gladiatorial games would often run for days on end, and would build momentum throughout the course of the event. Opening acts usually involved animals and would include games such as the venationes and the bestiarii. The venationes was essentially a staged, canned hunt where a hunter would pursue wild game throughout the arena to entertain the mob. Bestiarii involved man and beast engaging in mortal combat, and neither was guaranteed victory. As often as not, the beast emerged triumphant from these matches, much to the pleasure of the crowd. Following these games, the attention would turn to the main events, where gladiators would engage in single combat. It was also not unusual in larger venues to stage historical reenactments, placing trained warriors on the historically winning side against poorly armed and untrained criminals on the historically losing side.

The great bloodshed from these bouts was absorbed into the sand that was layered on the arena’s floor for this express purpose. And that is where we get the word “arena,” from “harena,” the Latin word for sand.

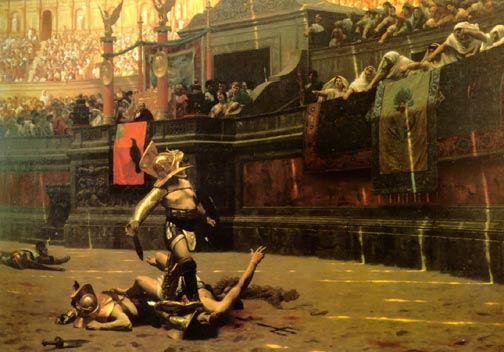

Pollice Verso

Although motivations were mixed when a man stepped into the arena as a gladiator, by the time swords clashed all men shared only one motivation…survival. This decision rested not only on their grit, courage, and skill-at-arms, however, but also with the mob. Should a gladiator be bested by his opponent and find himself about to receive a mortal blow, his fate was often decided pollice verso (with a turned thumb). A victorious and reputation-conscious gladiator would often choose to involve the mob, looking to them for guidance on whether he should finish off his opponent. With the turn of their thumbs, the Roman mob could seal the man’s fate. The common perception is that it was thumbs up for life, thumbs down for a quick end. There are some scholars who argue that the reverse of this was true, and that an upturned thumb towards the throat represented the desire to see the conquered opponent slain, but the truth may forever be lost to history. Regardless, we do know for certain that the mob often held the fallen gladiator’s fate in their hands. For a gladiator who had fought valiantly, the crowd was likely to vote for mercy.

If a gladiator’s life was spared, it was back to training and preparing himself to become once again…the man in the arena.

What is your take on gladiator games? Will future generations look back on our varying forms of entertainment with a similar shock and fascination? Let us know in the comments!

Sources

“Gladiators” by Michael Grant, Barnes and Noble Books, 1967

“The Gladiators – History’s Most Deadly Sport” by Fik Meijer, St Martin’s Griffin, 2007

“Gladiators” by Stephen Wisdom, Osprey publishing, 2001