We live in a world that’s highly technical and specialized. When a man goes to college these days, he spends his time learning the skills that will allow him to seek gainful employment. Little time is spent studying art or literature. These subjects are often seen as “pointless” because they don’t have any practical application when it comes to paying the bills. On top of that, many men see art appreciation as wussy and effeminate and thus steer clear of it.

But it’s a shame that many men feel this way about art because they’re missing out on poignant insights about what it means to be human and what it means to be a man. Art can capture the emotions of the human experience when words fail us, give us insight into positive madness, expand our minds, and help us learn more about the world and ourselves.

If you feel like you missed out on a basic art education or if you learned plenty about art history, but you need a refresher, this series we’re starting today is just for you. Over the next few months, we’ll be covering some of the simple basics of the important periods of Western art. Next time you’re on a date at a museum, you’ll have a few things to add to the conversation. But more importantly, you’ll be able to get more out of the art yourself and hopefully be inspired to delve deeper into the fruits of man’s infinite creativity. As you take time to ponder and mediate on some of history’s greatest works of art, you’ll gain a deeper appreciation for art’s manly heritage, experience uplift and edification, and find yourself closer to becoming a true Renaissance Man.

Speaking of the Renaissance, let’s get started talking about that period’s art.

An Introduction to the Basics of Renaissance Art

Time Period: 1400s-1600s

Background: The 14th century was a time of great crisis; the plague, the Hundred Years war, and the turmoil in the Catholic Church all shook people’s faith in government, religion, and their fellow man. In this dark period Europeans sought a new start, a cultural rebirth, a renaissance.

The Renaissance began in Italy where the culture was surrounded by the remnants of a once glorious empire. Italians rediscovered the writings, philosophy, art, and architecture of the ancient Greeks and Romans and began to see antiquity as a golden age which held the answers to reinvigorating their society. Humanistic education, based on rhetoric, ethics and the liberal arts, was pushed as a way to create well-rounded citizens who could actively participate in the political process. Humanists celebrated the mind, beauty, power, and enormous potential of human beings. They believed that people were able to experience God directly and should have a personal, emotional relationship to their faith. God had made the world but humans were able to share in his glory by becoming creators themselves.

These new cultural movements gave inspiration to artists, while Italy’s trade with Europe and Asia produced wealth that created a large market for art. Prior to the Renaissance Period, art was largely commissioned by the Catholic Church, which gave artists strict guidelines about what the finished product was to look like. Medieval art was decorative, stylized, flat, and two-dimensional and did not depict the world or human beings very realistically. But a thriving commercial economy distributed wealth not just to the nobility but to merchants and bankers who were eager to show their status by purchasing works of art (the Church remained a large patron of the arts as well). Artists were allowed greater flexibility in what they were to produce, and they took advantage of it by exploring new themes and techniques.

Things to Look for in Renaissance Art:

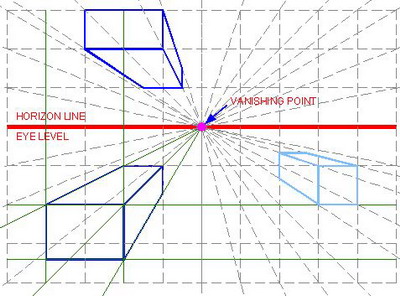

- Perspective. To add three-dimensional depth and space to their work, Renaissance artists rediscovered and greatly expanded on the ideas of linear perspective, horizon line, and vanishing point.

- Linear perspective: Rendering a painting with linear perspective is like looking through a window and painting exactly what you see on the window pane. Instead of every object in the picture being the same size, objects that were further away would be smaller, while those closer to you would be larger.

- Horizon line: Horizon line refers to the point in the distance where objects become so infinitely small, that they have shrunken to the size of a line.

- Vanishing point: The vanishing point is the point at which parallel lines appear to converge far in the distance, often on the horizon line. This is the effect you can see when standing on railroad tracks and looking at the tracks recede into the distance.

- Shadows and light. Artists were interested in playing with the way light hits objects and creates shadows. The shadows and light could be used to draw the viewer’s eye to a particular point in the painting.

- Emotion. Renaissance artists wanted the viewer to feel something while looking at their work, to have an emotional experience from it. It was a form of visual rhetoric, where the viewer felt inspired in their faith or encouraged to be a better citizen.

- Realism and naturalism. In addition to perspective, artists sought to make objects, especially people, look more realistic. They studied human anatomy, measuring proportions and seeking the ideal human form. People looked solid and displayed real emotions, allowing the viewer to connect with what the depicted persons were thinking and feeling.

Examples:

Let’s start out by looking at two different paintings of the Virgin Mary, one from the Byzantine period, and one from the Renaissance period, so that you can get a feel for the profound transformation art went through during the Renaissance:

Madonna and Child on a Curved Throne, 1200’s. In this wood panel painting from the Byzantine period, the bodies of Mary and Jesus are bodiless and hidden in drapery. The folds of the drapery are represented by gold leaf striations; even where you would see knees, you have an accumulation of gold instead of light and shadow. The picture lacks the feeling of depth and space. Also, Jesus is portrayed as an infant, but looks like a miniature adult.

Madonna del Cardellino, by Raphael, 1506. Now we’re well into the Renaissance and the changes in style are readily apparent. Mary has become much more realistically human; she has a real form, real limbs, a real expression on her face. Not only does she look natural, but she is placed is a natural setting. Jesus and John the Baptist look like real babies, not miniature adults. Raphael utilized perspective to give the painting depth. He also captured the Renaissance’s love of combining beauty and science-bringing back things like geometry from the ancient Greeks: Mary, Christ, and John the Baptist form a pyramid.

Tribute Money, by Masaccio, 1425. Masaccio was a pioneer in the technique of one point perspective; the painting is an image of what one person looking at the scene would see. Notice how Peter, next to the water, and the mountains are paler and less clear than the objects in the foreground. The lines in the painting meet atop Jesus’ head in a vanishing point. It appears that the figures are lit by light from the chapel, as their shadows all fall away in the same direction. Such a touch seems basic to us today, but incorporating a light from a specific source and using it to lend figures three-dimensionality was groundbreaking for the time.

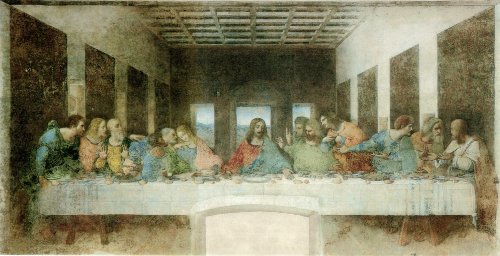

The Last Supper, by Leonardo da Vinci, 1498. An example of the way in which Renaissance artists wished to draw the viewer into the painting by depicting a vibrant scene filled with real psychology and emotion. All the apostles have different reactions to Christ revealing that one will betray him. Like in the Tribute Money, Jesus’ head is located at the vanishing point for all the perspective lines.

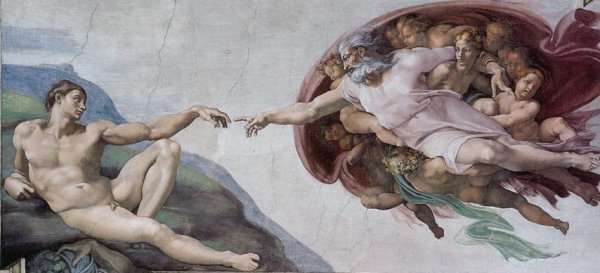

The Creation of Adam, by Michelangelo, 1511. In this most famous section of the Sistine Chapel, the personal nature of faith, the divine potential of man, and the idea of man being co-creator with God is vividly depicted. So is the Renaissance interest in anatomy; God is resting on the outline of the human brain. Michelangelo, like Leonardo, performed numerous dissections of human corpses in order to gain an in-depth and realistic look at the parts and structure of the human body.

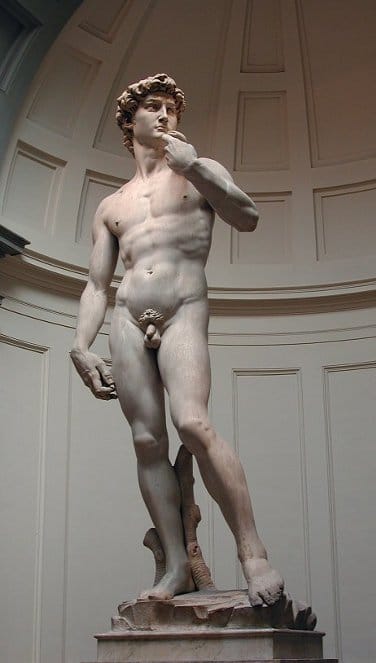

David, by Michelangelo, 1504. Renaissance artists created the first free-standing nude statutes since the days of antiquity. Michelangelo believed that sculpture was the highest form of art as it echoes the process of divine creation. His David is the perfect example of the Renaissance’s celebration of the ideal human form. The statue conveys rich realism in form, motion, and feeling. The upper body and hands are not quite proportional, perhaps owing to the fact that the work was meant to be put on a pedestal and viewed by looking upwards. Michelangelo was a master at portraying subjects at moments of psychological transition, as if they had just thought of something, and this statue is often believed to be depicting the moment when David decides to slay Goliath.

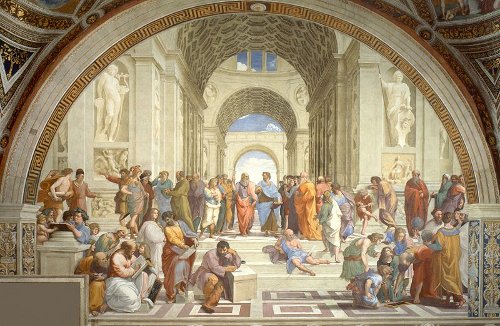

School of Athens, by Raphael, 1510. This painting, which depicts all the great philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome, serves as an example of the way in which Renaissance artists were inspired by and hearkened back to the days of antiquity. The perspective lines draw the viewer to the center of the painting and the vanishing point where history’s two greatest philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, stand. In line with their philosophies, Plato points to the heavens and the realm of Forms, while Aristotle points to the earth and the realm of things.

The Basics of Art Series

The Renaissance

The Baroque Period

The Romantic Period