This is the second in a series on classical rhetoric. In this post, we lay the foundation of our study of rhetoric by taking a look at its history. While this post is in no way a comprehensive history of rhetoric, it should give you enough background information to understand the context of the principles we’ll be discussing over the next few months.

Humans have studied and praised rhetoric since the early days of the written word. The Mesopotamians and Ancient Egyptians both valued the ability to speak with eloquence and wisdom. However, it wasn’t until the rise of Greek democracy that rhetoric became a high art that was studied and developed systematically.

Rhetoric in Ancient Greece: The Sophists

Many historians credit the ancient city-state of Athens as the birthplace of classical rhetoric. Because Athenian democracy marshaled every free male into politics, every Athenian man had to be ready to stand in the Assembly and speak to persuade his countrymen to vote for or against a particular piece of legislation. A man’s success and influence in ancient Athens depended on his rhetorical ability. Consequently, small schools dedicated to teaching rhetoric began to form. The first of these schools began in the 5th century B.C. among an itinerant group of teachers called the Sophists.

The Sophists would travel from polis to polis teaching young men in public spaces how to speak and debate. The most famous of the Sophists schools were led by Gorgias and Isocrates. Because rhetoric and public speaking were essential for success in political life, students were willing to pay Sophist teachers great sums of money in exchange for tutoring. A typical Sophist curriculum consisted of analyzing poetry, defining parts of speech, and instruction on argumentation styles. They taught their students how to make a weak argument stronger and a strong argument weak.

Sophists prided themselves on their ability to win any debate on any subject even if they had no prior knowledge of the topic through the use of confusing analogies, flowery metaphors, and clever wordplay. In short, the Sophists focused on style and presentation even at the expense of truth.

The negative connotation that we have with the word “sophist” today began in ancient Greece. For the ancient Greeks, a “sophist” was a man who manipulated the truth for financial gain. It had such a pejorative meaning that Socrates was executed by the Athenians on the charge of being a Sophist. Both Plato and Aristotle condemned Sophists for relying solely on emotion to persuade an audience and for their disregard for truth. Despite criticism from their contemporaries, the Sophists had a huge influence on developing the study and teaching of rhetoric.

Rhetoric in Ancient Greece: Aristotle and The Art of Rhetoric

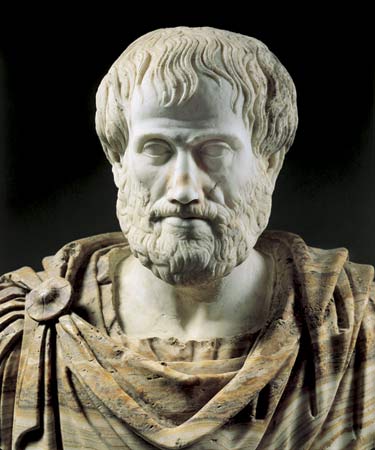

While the great philosopher Aristotle criticized the Sophists’ misuse of rhetoric, he did see it as a useful tool in helping audiences see and understand truth. In his treatise, The Art of Rhetoric, Aristotle established a system of understanding and teaching rhetoric.

While the great philosopher Aristotle criticized the Sophists’ misuse of rhetoric, he did see it as a useful tool in helping audiences see and understand truth. In his treatise, The Art of Rhetoric, Aristotle established a system of understanding and teaching rhetoric.

In The Art of Rhetoric, Aristotle defines rhetoric as “the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.” While Aristotle favored persuasion through reason alone, he recognized that at times an audience would not be sophisticated enough to follow arguments based solely on scientific and logical principles. In those instances, persuasive language and techniques were necessary for truth to be taught. Moreover, rhetoric armed a man with the necessary weapons to refute demagogues and those who used rhetoric for evil purposes. According to Aristotle, sometimes you had to fight fire with fire.

After establishing the need for rhetorical knowledge, Aristotle sets forth his system for effectively applying rhetoric:

- Three Means of Persuasion (logos, pathos, and ethos)

- Three Genres of Rhetoric (deliberative, forensic, and epideictic)

- Rhetorical topics

- Parts of speech

- Effective use of style

The Art of Rhetoric had a tremendous influence on the development of the study of rhetoric for the next 2,000 years. Roman rhetoricians Cicero and Quintilian frequently referred to Aristotle’s work, and universities required students to study The Art of Rhetoric during the 18th and 19th centuries.

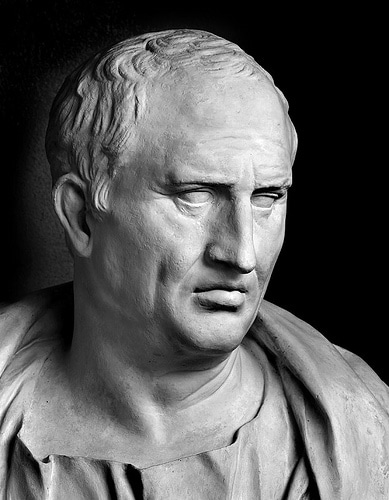

Rhetoric in Ancient Rome: Cicero

Rhetoric was slow to develop in ancient Rome, but it started to flourish when that empire conquered Greece and began to be influenced by its traditions. While ancient Romans incorporated many of the rhetorical elements established by the Greeks, they diverged from the Grecian tradition in many ways. For example, orators and writers in ancient Rome depended more on stylistic flourishes, riveting stories, and compelling metaphors and less on logical reasoning than their ancient Greek counterparts.

The first master rhetorician Rome produced was the great statesman Cicero. During his career he wrote several treatises on the subject including On Invention, On Oration, and Topics. His writings on rhetoric guided schools on the subject well into Renaissance.

Cicero’s approach to rhetoric emphasized the importance of a liberal education. According to Cicero, to be persuasive a man needed knowledge in history, politics, art, literature, ethics, law, and medicine. By being liberally educated, a man would be able to connect with any audience he addressed.

Rhetoric in Ancient Rome: Quintilian

The second Roman to leave his mark on the study of rhetoric was Quintilian. After honing his rhetorical skills for years in the Roman courts, Quintilian opened a public school of rhetoric. There he developed a study system that took a student through different stages of intense rhetorical training. In 95 AD, Quintilian immortalized his rhetorical education system in a twelve-volume textbook entitled Institutio Oratoria.

Institutio Oratoria covers all aspects of the art of rhetoric. While Quintilian focuses primarily on the technical aspects of effective rhetoric, he also spends a considerable amount of time setting forth a curriculum he believes should serve as the foundation of every man’s education. In fact, Quintilian’s rhetorical education ideally begins as soon as a baby is born. For example, he counsels parents to find their sons nurses that are articulate and well-versed in philosophy.

Quintilian devotes much of his treatise to fleshing out and explaining the Five Canons of Rhetoric. First seen in Cicero’s De Inventione, the Five Canons provide a guide on creating a powerful speech. The Five Canons are:

- inventio (invention): The process of developing and refining your arguments.

- dispositio (arrangement): The process of arranging and organizing your arguments for maximum impact.

- elocutio (style): The process of determining how you present your arguments using figures of speech and other rhetorical techniques.

- memoria (memory): The process of learning and memorizing your speech so you can deliver it without the use of notes. Memory-work not only consisted of memorizing the words of a specific speech, but also storing up famous quotes, literary references, and other facts that could be used in impromptu speeches.

- actio (delivery): The process of practicing how you deliver your speech using gestures, pronunciation, and tone of voice.

If you’ve taken a public speaking class, you were probably taught a version of the Five Canons. We’ll be revisiting these in more detail in a later post.

Rhetoric in Medieval Times and the Renaissance

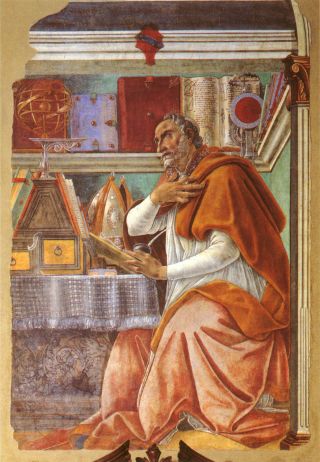

During the Middle Ages, rhetoric shifted from political to religious discourse. Instead of being a tool to lead the state, rhetoric was seen as a means to save souls. Church Fathers, like St. Augustine, explored how they could use the “pagan” art of rhetoric to better spread the gospel to the unconverted and preach to the believers.

During the latter part of the Medieval period, universities began forming in France, Italy, and England where students took classes on grammar, logic, and (you guessed it) rhetoric. Medieval students poured over texts written by Aristotle to learn rhetorical theory and spent hours repeating rote exercises in Greek and Latin to improve their rhetorical skill. Despite the emphasis on a rhetorical education, however, Medieval thinkers and writers made few new contributions to the study of rhetoric.

Like the arts and sciences, the study of rhetoric experienced a re-birth during the Renaissance period. Texts by Cicero and Quintilian were rediscovered and utilized in courses of study; for example, Quintilian’s De Inventione quickly became a standard rhetoric textbook at European universities. Renaissance scholars began producing new treatises and books on rhetoric, many of them emphasizing applying rhetorical skill in one’s own vernacular as opposed to Latin or ancient Greek.

Rhetoric in the Modern Day

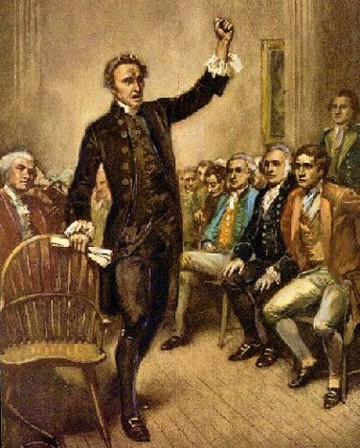

The rejuvenation of rhetoric continued through the Enlightenment. As democratic ideals spread throughout Europe and the American colonies, rhetoric shifted back from religious to political discourse. Political philosophers and revolutionaries used rhetoric as a weapon in their campaign to spread liberty and freedom.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, universities in both Europe and America began devoting entire departments to the study of rhetoric. One of the most influential books on rhetoric that came out during this time was Hugh Blair’s Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles-Lettres. Published in 1783, Blair’s book remained a standard text on rhetoric at universities across Europe and America for over a hundred years.

The proliferation of mass media in the 20th century caused another shift in the study of rhetoric. Images in photography, film, and TV have become powerful tools of persuasion. In response, rhetoricians have expanded their repertoire to include not only mastery of the written and spoken word, but a grasp of the visual arts as well.

Alright, that does it for this edition of Classical Rhetoric 101. Join us next time as we explore the Three Persuasive Appeals in rhetoric.

Classical Rhetoric 101 Series

An Introduction

A Brief History

The Three Means of Persuasion

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Invention

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Arrangement

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Style

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Memory

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Delivery

Logical Fallacies

Bonus! 35 Greatest Speeches in History