Editor’s note: This is a guest post from Tony Valdes.

Greek mythology might sound like an obscure area of study, as if it is only relevant to wizened old professors in posh offices at Ivy League schools. Or perhaps you associate the topic with vague memories of sensationalized Hollywood summer movies. Ancient Greek culture, however, contributes much more to the modern world than we might realize.

The influence of the Greek mythology on western civilization began when the Romans adopted the pantheon of Greek gods; this subsequently influenced the names of the planets in our solar system. Fast forward through history and you will find evidence of the Greeks in art, books, poetry, movies, television, and popular culture. For example, every time you don a pair of Nike shoes, you emblazon yourself with the name of the Greek goddess of victory, whose name was, of course, Nike. A company that makes athletic clothing is trying to say something about itself and those who wear their products by choosing such a name, don’t you think? Likewise, Midas auto shop, Honda’s “Odyssey” minivan, the Olympic games, and literary heavyweights such as William Shakespeare, Dante Alighieri, and Mary Shelley have all taken cues from the Greeks. And this barely scratches the surface.

Acquiring a working knowledge of mythology can enrich a man’s life and open cultural doors that would otherwise remain locked. I would compare being knowledgeable about Greek mythology to one of my all-time favorite heroes: Indiana Jones. Remember how Indy seemed to have all that really obscure knowledge about myths, legends, and religions from bygone eras? And remember how awesome it was when he could look at some artifact, document, or piece of architecture and connect the dots? With a little bit of effort, we can do the same, and we aim to do just that in this series on the basics of Greek mythology for the modern man. At the end of this series, I will offer you a fun challenge where you can be your own Dr. Jones and impress a lovely lady in your life. Let’s get started…

What Is Myth?

Although we often associate the word “myth” with ancient systems of make-belief religions, a myth is actually a set of stories that is significant to a culture. Although they tend to be fictional, it is not a requirement. Thus Zeus, Superman, Area 51, the Loch Ness Monster, and George Washington can all be considered parts of various mythologies.

George Washington may seem like an odd part of that list, but consider the “larger than life” status that American history has given to our first president. Although he existed in reality, he is no longer simply a man: Washington is a symbol packed with meaning for our nation. Along with fictitious characters like Superman, Washington is a significant part of what defines the American way of thinking. They are eternally linked with who we are and what we believe.

The Problem with Greek Mythology

Before diving into the colorful world of the Greek stories, it is important that we understand that Greek mythology is rife with inconsistencies. In other words, many of the stories are going to sound absolutely ridiculous and, at times, even contradict each other.

When considering these stories, we must remember that the Greeks were creating stories based on their own fallible human nature. Thus the Greek gods are often as cruel, inconsistent, and sinful as humans are. Also keep in mind that the Greeks were not attempting to create a system of absolute truth; they were simply telling stories to explain the world around them. If you were having a good day, then Zeus was a kind and benevolent god. If you were having a lousy day, then Zeus was vengeful and merciless.

We could compare this point to some of our modern mythology. Let’s go back and consider Superman again. In some stories a piece of kryptonite the size of a pebble is enough to bring the Man of Steel to his knees in agony; in other stories it takes a chunk the size of a basketball to induce tortuous pain. It all depends on who is telling the story and his or her view of Superman’s weaknesses and strengths. Likewise, Batman swings on a pendulum that ranges from the campy Adam West portrayal to the gritty trilogy created by Christopher Nolan.

There is one more point that needs clarifying: when the Romans adopted Greek mythology, they gave Roman names to each of the characters. For our purposes here we’ll refer to everyone by his or her Greek name, but when applicable the Roman name will be included in parenthesis.

With that being said, let’s begin exploring the stories.

The War of Deities

According to the Greeks, in the beginning of time there was Father Heaven (Uranus) and Mother Earth (Gaea). Together, they bore children known as the Titans. Cronus (Saturn) and Rhea (Cybele) led the Titans in a rebellion against Father Heaven and Mother Earth. The Titans defeated their parents and became the rulers of the heavens.

In turn, Cronus and Rhea had children known as the Olympians. The Olympians are the Greek gods as we know them, led by Zeus and Hera. Cronus, concerned that his children would overthrow him in the same way that he overthrew Father Time, devoured his children. Rhea, however, defied Cronus by tricking him into eating a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes in place of the infant Zeus.

When Zeus came of age, he was outraged to learn the fate of his brothers and sisters. Zeus ambushed Cronus and forced him to vomit up the Olympians, who had apparently survived and grown to maturity in Cronus’ stomach. With the help of Prometheus, a rogue Titan, the Olympians defeated Cronus and Zeus took his place as ruler of the heavens. Zeus punished most of the Titans by imprisoning them; however, the Titan named Atlas received a unique punishment: he was doomed to carry the weight of the world upon his shoulders. Prometheus, since he aided the Olympians, was not punished.

The Olympians

Although Zeus was the most powerful of the Olympians and thus the leader, he delegated control of the universe to his brothers and sisters. Zeus, Poseidon, Hades, Hera, Demeter, and Hestia were the children of Cronus and the original six Olympians; all additional Olympians were children of Zeus (though not all were birthed by traditional means).

With the exception of Hades, who was often depicted dwelling in Tartarus, all of the Greek gods lived in splendor in a city that they named Olympus. This majestic city hovered high above a mountain, which was named Mount Olympus as a result. Mighty clouds served as the gates of Olympus and it was said that no rough wind or foul weather ever shook the city of the gods.

The Olympians – the sons and daughters of Cronus – and their offspring were center stage of all of mythology and understanding the character of each is crucial to understanding every narrative within Greek mythology, so let’s take a moment to look at the twelve that are referenced most frequently.

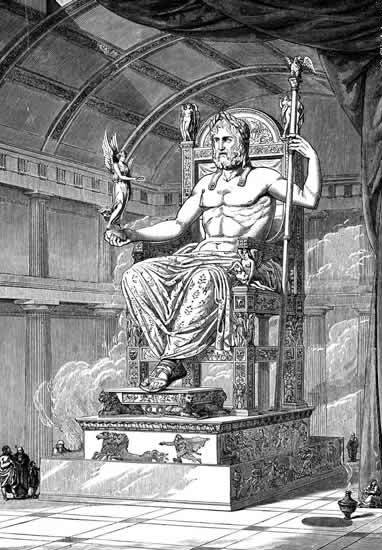

Zeus (Jupiter)

After the overthrow of the Titans, Zeus was not only the leader of the Olympians but also the ruler of the universe. Symbolized by the eagle and wielding lightening bolts as his weapon of choice, there were few who had the courage to challenge even the simplest aspects of Zeus’ will. Those who did often did so through trickery and guile rather than through direct confrontation. Depending on the story, Zeus’s personality could range from a benevolent father figure to detached, all-powerful tyrant. Because the Greek gods mirrored all the same faults and foibles as humanity, Zeus could make mistakes and be deceived. He was often a skirt-chaser as well, taking a variety of bizarre forms (including but not limited to bulls, swans, and golden rain) to seduce mortal woman. Shakespeare recounted one more notable encounter in his poem titled “The Rape of Lucretia.” Super-human demigods like Hercules and Perseus were said to be Zeus’ children with mortal women.

Poseidon (Neptune)

A brother of Zeus and the god of the seas, Poseidon was also responsible for earthquakes, which earned him the moniker “earth shaker.” His was often portrayed wielding a trident, which he uses to churn the oceans and create storms. Though he was certainly not as powerful as Zeus, Poseidon was not to be trifled with. His dominion over the oceans and influence on land could make or break a sea-faring culture like that of the Greeks. Poseidon was credited with the creation of all sea life, but when the other god and goddesses mocked Poseidon’s creations (fish and other sea life), they challenged him to create something beautiful. In response, he created horses.

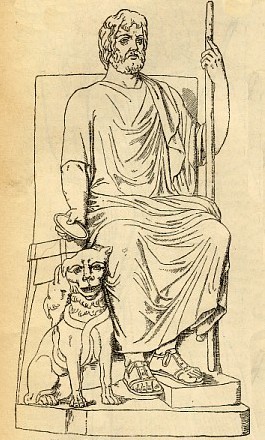

Hades (Pluto)

Contrary to popular belief and Disney’s Hercules, Hades was not the Greek equivalent of the devil in Judeo-Christian tradition. A brother of Zeus and Poseidon, Hades simply got the short stick when the Olympian brothers divvied up their domains. Hades ruled over the underworld, also known as Tartarus. Unlike the Judeo-Christian concept of heaven and hell, all souls – whether good or evil – arrived in Tartarus where Hades was responsible for their care. The only exception to this rule was “Isle of the Blessed,” which we will see when we examine the Greeks’ concept of geography. There was some degree of punishment for the wicked and reward for the just, but not to the same degree as the heaven and hell dichotomy. Hades was the only Olympian who did not make his home atop Mount Olympus. He brooded in Tartarus with his three-headed dog Cerberus, who guarded the gates and prevented the living from entering and the dead from leaving. Hades wife, Persephone, was a mortal woman whom Hades abducted. Persephone’s mother, Demeter, and Olympian, struck a deal with Hades that her daughter would spend half the year with her and the other half in the underworld with him. The Greeks believed that the result of this deal was spring/summer when Persephone was with her mother and fall/winter when she was with her husband.

Hera (Juno)

Hera was the wife of Zeus and, ironically, the goddess of fidelity. As you can imagine, she was particularly irritable when Zeus seduced fellow goddesses or, worse, mortal women. To be mortal and the object of Zeus’ affections was a curse; not only would the woman have to explain the odd circumstances surrounding her child’s birth, but she would also suffer the wrath of Hera, which could be cruel indeed. Furthermore, the child the woman bore would suffer as well. No one knows this better than poor Hercules, whom we’ll discuss in more detail later. Hera was symbolized by the peacock and, though she rarely engaged in any sort of combat herself, she was cunning, stealthy, and held sway over her husband, making her formidable in a way no other Olympian could boast of being.

Hestia (Vesta)

Hestia wasn’t as flashy or dramatic as many of the other Olympians, thus she rarely got the spotlight, but that does not diminish her importance to the Greeks. She was the goddess of the hearth, which meant that if you had a comfortable home and a happy family then Hestia had blessed you.

Demeter (Ceres)

Like Hestia, Demeter was often upstaged by her fellow Olympians. She was the goddess of grain, which made her very important to everyday life.

Pallas Athena (Minerva)

Pallas Athena, usually referred to simply as Athena, was the goddess of wisdom. The Greek hoplite helmet she wore perched atop her head easily identified her. She was frequently shown with a shield and spear in hand as well. Though she is not directly associated with war (that accolade goes to Ares) Athena was nonetheless frequently involved in the Greeks’ battles. If Ares was the savage brutality and strength of war, Athena was the cunning, strategic side of it. She was most famous for her regard of Odysseus, whom was known as the cleverest of all the Greeks. Like much of mythology, there are conflicting stories about Athena’s origin; however, the most widely known is that she sprang full-grown from Zeus’ head, which sounds terribly painful for both parties if you ask me.

Apollo (Apollo)

Apollo was very popular with the Greeks as he was the god of truth and prophecy. Temples and oracles were scattered all over Greece that boasted of having a direct line to Apollo; however, the most prestigious of these was the Oracle at Delphi. It was common for Greek kings to consult Apollo regarding war and political conflicts. The Olympian was no stranger to combat; his weapon of choice was the bow, but he was also frequently pictured with a lyre, which displays the diverse qualities of this particular god.

Hermes (Mercury)

Hermes was a curious looking Olympian: he wore a helmet that looked something like a bowl with wings sprouting from it. In addition, his sandals had wings and he carried a scepter (the winged rod entwined with snakes that we now use as a symbol for medical practice). He was the messenger god, a sort of mailman for Olympus and, like the angels sometimes do in Scripture, declares the will of Zeus to the mortal world. As you can infer from his winged attire, Hermes could move with great speed. Interestingly, Hermes was also the god of thieves. You would think someone more reliable would be chosen as Zeus’ mouthpiece, but as far as I know Hermes never took advantage of his status to pull off any capers.

Artemis (Diana)

Like Hestia and Demeter, Artemis rarely took center stage. She was the goddess of the hunt and preservation of the wild. Like the aforementioned goddesses, Artemis was essential to the daily lives of the Greeks, but didn’t make for very compelling stories.

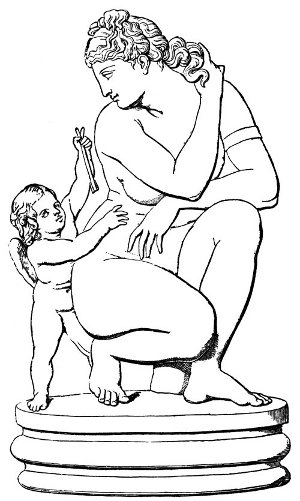

Aphrodite (Venus)

Ah, Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty and love. Much could be said about this Olympian, but let it suffice to say she stood out even amidst the physical perfection of the Olympians. As you can imagine, Aphrodite frequently had her lovely fingers entwined in the more memorable Greek myths. Her long blonde hair strategically covering her lady parts makes her instantly recognizable in many Renaissance paintings; however, she just as often bares all. There are conflicting stories regarding her birth, but the idea that she sprung forth out of the foam of the sea seems to be the most popular due to Sandro Botticelli’s painting titled “The Birth of Venus.”

Ares (Mars)

Ares was the infamous god of war. He was not the sort of god the Greeks would consult like Zeus, Apollo, or Athena, but rather he was a personified savage force of nature. He was quite intimidating on the battlefield until he was wounded, at which point he would bellow in rage and flee to Olympus. Ares also had a torrid love affair with Aphrodite, which came back to bite him in a significant way.

Hephaestus (Vulcan)

Only one Olympian was outright butt-ugly. Poor Hephaestus was so unsightly that his mother, Hera, cast him off of the peak of Olympus when he was born. As a result, Hephaestus walked with a limp. He functioned as the god of fire and forging, and everything he created was flawless, unbreakable, and of tremendous value. To have a goblet made by Hephaestus was an honor, but to have a weapon or armor forged by this Olympian was a privilege. Subsequently, Hephaestus forged the lightening bolts for his father, Zeus. The great irony of Hephaestus was that his wife was the lovely Aphrodite. That marriage – and Aphrodite’s subsequent affair with Ares – did not go unnoticed in the Greeks’ stories. When Hephaestus learned of his wife’s infidelity, he forged a net in which to capture his wife in the act of her betrayal. One day while Aphrodite and Ares were – ahem – “meeting” with each other, Hephaestus burst into the room and cast the net over the top of them, and then called the other gods to openly mock Ares and Aphrodite caught in the midst of their shameful act. All is fair in love and war, I suppose.

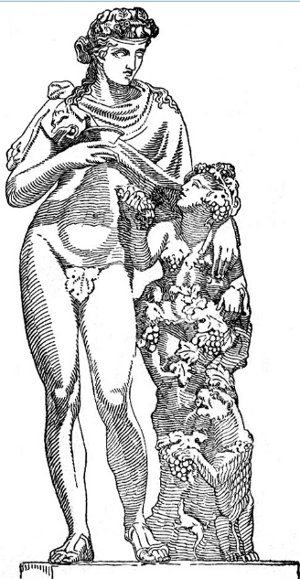

Dionysus (Bacchus)

Lastly we have Dionysus, the god of wine and festivity. Though he may not have been essential to survival like some of the lesser-known goddesses or be featured prominently in the drama on Olympus, Dionysus was by far the favorite of the Greeks. Theatre, celebrations, athletic competitions, and rich wine all fell under the jurisdiction of Dionysus.

Today’s Wrap Up

Every culture and era has its beliefs about deities and their roles in the universe, but only a handful have been as enduring and influential as Greek mythology. Their pantheon was neither a religion nor a set of cultural fables, but rather something that landed right between those marks.

I think that’s more than enough for us to chew on today. We could certainly discuss at length the rest of the Greek pantheon, which includes other gods and goddesses as well as lesser supernatural beings, but these twelve are the necessary pieces. In the next post of this series, we will leave the lofty heights of Olympus and examine the mortal world as seen through the eyes of Greek mythology.

Primer on Greek Mythology Series:

The Gods and Goddesses

The Mortal World and Its Heroes

The Trojan War

The Odyssey and Applying What We’ve Learned