Today we will cover the second of three archetypes of American manliness proposed by Michael Kimmel in his book, Manhood in America. But before we delve into describing the Heroic Artisan, I think it would be beneficial to briefly review just what an archetype is. I noticed some confusion in the comments about the Genteel Patriarch stemming from reading the description of that archetype as straightforward history.

An archetype is a symbol, an ideal example, a model or prototype. These symbols stand in for a set of qualities and characteristics and are part of the cultural consciousness; we pattern ourselves after them. Archetypes may arise from real historical circumstances, but their correspondence to “reality” varies. An example of a distinctly American archetype would be the cowboy. Just hearing the word cowboy conjures up images of the rough and rugged loner, trotting along on his trusty steed in the desert, playing cards, and getting into shootouts in town. The reality of the American cowboy was quite different-“real” cowboys entered into unions, worked long, unglamorous hours on cattle drives, and rarely, if ever got into showdowns. But the archetype of the cowboy says something about how we think of ourselves as Americans-gritty and self-reliant, forged in a wild past. And this symbol informs our identity.

So it is with these three archetypes of American manliness. What we are describing in this series is both the history which beget and diminished the archetype and the ideal that the archetype represented. These archetypes are symbols of manliness-part history, part idealized legend.

With that out of the way, let us dive into the Heroic Artisan archetype.

The Heroic Artisan

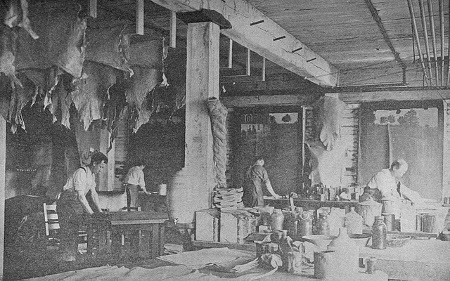

According to Kimmel, the Heroic Artisan, like the Genteel Patriarch, was an ideal of masculinity transplanted from Europe to the American colonies. He was the honest craftsman, sleeves rolled up, apron tied around his body, toiling away in his small, independently-owned shop. The Heroic Artisan could be found working and tinkering in breweries, printing houses, and blacksmith shops throughout the new nation. Farmers who owned and worked small pieces of land (unlike the Genteel Patriarch’s vast estates) could also be counted among the ranks of the Heroic Artisan.

For the Heroic Artisan, manliness meant primarily independence and self-reliance. His independence made him an invaluable citizen of the new republic: a man whose vote could not be bought or sold. Although fiercely independent, the Heroic Artisan also valued community. He was loyal to his fellow craftsmen, treated his customers/neighbors fairly, and embraced his civic duties. He was the patriarch of his family, and with his shop often located in or near his family’s house, was able to oversee his household throughout the day.

Work relationships were very personal for the Heroic Artisan. He didn’t hire random strangers to work in his shop, but took in the sons of neighbors and friends as apprentices, teaching them all the secrets of his craftsman’s guild. Thus, the Heroic Artisan didn’t see himself as merely a boss, but rather as a mentor who had a responsibility not only to mold his young apprentice into a master craftsman, but also to initiate him into manhood.

The Heroic Artisan was driven by a philosophy of producerism, a code which said that manly virtue was only earned though hard work and creating more than you consumed. The Heroic Artisan made real, tangible, quality goods with his hands; there was a direct link between his labor and the final product. His work not only provided a living but also gave him an identity of which he could be proud. His products were made to last; they had to be-his personal reputation as a craftsman, and as a man, period, was on the line.

The Heroic Artisan saw the Genteel Patriarch’s decadent wealth as a corrupting influence on manliness. Extreme wealth, to the Heroic Artisan, made men lazy, slothful, and effeminate. And even if the Genteel Patriarch created more than he consumed, it didn’t count in the Heroic Artisan’s book because the Genteel Patriarch didn’t create that wealth with the sweat of his own brow, with his own rough worn hands. How one made his living was paramount to the Heroic Artisan.

The Decline of the Heroic Artisan

At the beginning of the 19th century, America was a nation of Heroic Artisans. Nine out of every ten American men owned their own shop, store, or small farm. However, this ideal of manliness would soon move from reality to archetype. As the United States became more industrialized throughout the 19th century, the Heroic Artisan quickly became nearly obsolete. Work that once required the knowledge and skill of a master craftsman could be done cheaper and faster with a machine.

Real wages for skilled labor declined as small craftsmen tried to compete with the large factories sprouting up across the American landscape. No longer able to support themselves or their families, many craftsmen and laborers closed down their shops and went to work in factories owned by another man. Instead of spending hours concentrating on skilled tasks, men were now given a single, mindless job to perform over and over again. Workers lost their physical connection to the final product and became alienated from their labor. The world seemed to have been flipped upside-down; those on the ground who actually made things were underpaid and undervalued while those at the very top, who made their living through invisible deals at an office thousands of miles away, cultivated enormous wealth. The Heroic Artisan had lost the autonomy he valued so much. This loss of independence was equated with a loss of manhood.

Historian Elliot Gorn posed the questions these when were now faced with:

“Where would a sense of maleness come from for the worker who sat at a desk all day? How could one be manly without independence? Where was virility to be found in increasingly faceless bureaucracies? How might clerks or salesmen feel masculine doing ‘women’s work’? What became of rugged individualism inside intensively rationalized corporations? How could a man be a patriarch when his job kept him away from home for most of his waking hours?”

However, the Heroic Artisan didn’t bow out without a fight. Throughout the 19th century, tradesmen formed working man’s political parties and unions in an attempt to hold onto their status, livelihoods, and political power. The pamphlets and literature put out by these parties extolled the virtue of the manly autonomy that trade and craft work provided, while equating factory work with political, economic, and even sexual emasculation. As one tradesman from 1834 saw it, the factory system was “calculated to change the character of a people from bold and free to enervated, dependent, and slavish.”

The battle against industrialization was futile, of course. The market economy demanded efficiency and cost cutting over craftsmanship and pride. The Heroic Artisan would not be the ideal or archetype that would guide American manliness into the 20th century. The Self-Made Man archetype was better suited for the impersonal, fast-paced, and industrialized society that America became after the Civil War.

The Heroic Artisan’s Influence on Modern American Manliness

The outsourcing of manufacturing jobs and the shift to an information economy has turned the Heroic Artisan into much more legend than reality. Many a cubicle-dweller has whiled away the time at work dreaming about owning a little shop, making furniture or repairing motorcycles. Comics like Dilbert and movies like Office Space mine humor from the alienation men feel from their work, and the ridiculousness of jobs which seem utterly unconnected to any tangible product or anything productive at all. Shop classes have been stripped from the curriculum of high schools, and blue collar jobs are undervalued and unappreciated. Learning a trade is sadly seen not as heroic, but as the resort of those who cannot hack it in college.

Yet the pull of the Heroic Artisan archetype is still felt by many men, a standard by which they unconsciously measure their lives. In fact, the further we move away from the Heroic Artisan archetype, the more we seem to long to be connected to it. No matter the ubiquity and prestige of white-collar work, there’s something deep in the male consciousness which longs to be working with one’s hands in some way. It is also what drives the masculine appreciation for quality, well-crafted goods. We admire and wish to support our craftsmen brothers, even if we ourselves will never belong to the guild. We want to know that real brow sweat and passion went into making something.

Savvy marketers understand the influence of the Heroic Artisan stereotype. They pitch products that involve accessorizing (like Toyota Scions) in an attempt to give men the feel of “creating.” Or they market their product as giving men access to the lineage of Heroic Artisans. This commercial for the new Jeep Cherokee is a prime example of this:

Other companies like LL Bean, Eddie Bauer, and Woolrich have started touting their history and heritage while rolling out new items that are modeled on products from their archives. And a new style sensibility has developed, with men ditching their Ed Hardy tees for flannel Woolrich shirts and axe slings. Men are increasingly eschewing cheap, mass-produced goods for those which claim an artisanal heritage are more expensive but made to last. Witness for example the popularity of blogs like A Continuous Lean. While they may not know it, adopters of this trend are really seeking to get in touch with the Heroic Artisan archetype.

3 Archetypes of American Manliness Series:

Part I: The Genteel Patriarch

Part II: The Heroic Artisan

Part III: The Self-Made Man