Since starting the Art of Manliness, I’ve read a lot about the history of masculinity across different cultures and time periods. One of the best books I’ve read on the history of manliness in the US is Michael Kimmel’s Manhood in America: A Cultural History (although my feelings on the conclusions he draws from that history are another story). In his book, Kimmel argues that during the late 18th century, when America was just in its infancy, three ideals of manhood competed for dominance: the Genteel Patriarch, the Heroic Artisan, and the Self-Made Man.

In the end, according to Kimmel, the Self-Made Man won out, and American manliness today is defined by the archetype of the rugged, self-reliant man who through sheer force of will can shape his destiny no matter his circumstances. While the Self-Made Man triumphed as the defining ideal of American masculinity, the Genteel Patriarch and the Heroic Artisan archetypes still influence how Americans think about manhood.

Over the course of the next few weeks, we’ll explore the attributes, history, and modern influence of these three archetypes of American manliness. Today we begin with the Genteel Patriarch.

The Genteel Patriarch

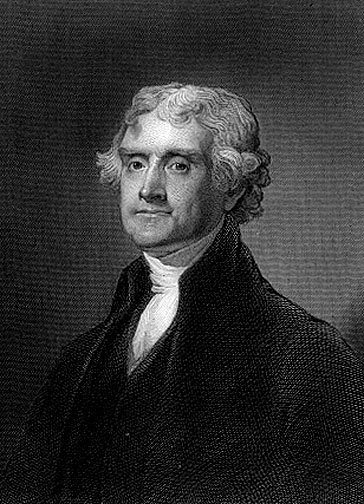

The Genteel Patriarch was an ideal of masculinity transplanted directly from Europe to the New World. The Genteel Patriarch defined manhood in terms of aristocratic landownership. He was an upper-class man who prized honor, character, and etiquette and had refined (i.e. European) tastes in clothing and food. The Genteel Patriarch sought to govern his vast estate with benevolence and kindness, and he spent much of his time doting on his children and ensuring they received the moral education they needed to be active and engaged citizens in the young republic.

The Genteel Patriarch was an ideal of masculinity transplanted directly from Europe to the New World. The Genteel Patriarch defined manhood in terms of aristocratic landownership. He was an upper-class man who prized honor, character, and etiquette and had refined (i.e. European) tastes in clothing and food. The Genteel Patriarch sought to govern his vast estate with benevolence and kindness, and he spent much of his time doting on his children and ensuring they received the moral education they needed to be active and engaged citizens in the young republic.

For the Genteel Patriarch, farming was the only occupation that offered total independence and self-autonomy. Through farming, a man could develop the virtues of honor, self-reliance, and hospitality. Landownership provided the Genteel Patriarch with status, identity, and a tradition on which to build a manly family lineage.

Of course what’s ironic about the Genteel Patriarch is that while he upheld agrarianism as the ideal, manly way of life, he himself rarely tilled the ground or sowed the seeds on his land. Rather, slaves or hired help did most of the manual labor while the Genteel Patriarch stayed busy studying art, philosophy, and literature.

While the archetype of the Genteel Patriarch was noble and virtuous, the reality was racist, discriminatory, and out of reach to the majority of men. Remember, for the Genteel Patriarch manhood meant primarily one thing: land ownership. If you didn’t own property, you weren’t a man. Right away this excluded the lower classes and of course black men, who in many states couldn’t even legally own land. Worse still, black men were often the property of the Genteel Patriarch, and made his leisurely, cultured lifestyle possible.

The Decline of the Genteel Patriarch

While the Genteel Patriarch made a strong start as the winning ideal of American manliness, his lead would not last long. This archetype was diminished by two factors: American Independence and the opening of the frontier. In the period after the Revolutionary War, the new country sought to form its own character and identity; affectations that smacked of monarchy and aristocracy fell out of favor as not sufficiently democratic or American. At the same time, pioneers were heading out West, and making a go at life on the frontier required a tougher, grittier kind of man than the Genteel Patriarch. Thus the Genteel Patriarch began to be seen as an anachronistic ideal, no longer in-sync with the changing culture of the nation. Once praised as the paradigm of stately dignity, he began to be seen as the foppish and effeminate dandy who had a “womanish attachment” to European countries, especially France.

As America shifted from an agrarian to an industrial society, the Genteel Patriarch quickly became an endangered species. His values and traditions didn’t transfer well to the new fast-paced market economy. Seeing that his days were numbered, the Genteel Patriarch made his last stand in the American South.

To the issues of slavery and states’ rights, we can add another question at stake on the battlefields of the Civil War: the competition between two ideals of manliness. The Northern press often characterized the Genteel Patriarch of the South as lazy, effeminate, and dandified, while lauding Northern men for embracing the hardy ideals of the Self-Made Man. Southerners countered that Yanks lacked refinement and honor, and cared for nothing in life other than the all mighty dollar. The South’s defeat in the Civil War brought the inevitable eclipse of the Genteel Patriarch and the ascendancy of the Self-Made Man as the ideal of American manhood.

The Genteel Patriarch’s Influence on Modern American Manliness

While the agrarian society of the Genteel Patriarch has long disappeared, the influence of this male archetype is still evident in American society. As he did in the 19th century, the Genteel Patriarch today serves as a foil to more popular forms of masculinity. Men who seem too cultured, refined, and style-conscious are sometimes dismissed as wimpy and not sufficiently masculine. It is now, as it was then, really a class issue-guided by the belief that only those with gobs of money have the time to attend to the minutiae of etiquette and fashion, while “real men” are too hard at work to notice such things. The Genteel Patriarch archetype remains suspect in many minds because of its perception as non-democratic.

This idea can most clearly be seen played out in the political arena. Ever since Andrew Jackson took the White House with a campaign promising to represent the common man, presidential candidates have had to make of a show of their rugged masculinity while downplaying characteristics that would mark them as the Genteel Patriarch, or in modern parlance, an “elitist.” A candidate must be intelligent, but not snobbishly so, articulate and well-mannered, but able to drink beer with factory workers and eat corn dogs at state fairs.

A familiar tactic in modern campaigns is for the conservative candidate to grab the democratic, common man mantle, while painting his liberal rival as the out-of-touch, dandified, Europe-admiring Genteel Patriarch. Of course both candidates typically have traits befitting this archetype, which leads to a battle to see who is best at spinning their own cultured background and attacking their contenders’. In the 1988 election, George HW Bush characterized Dukakis’ views as “born in Harvard-Yard’s boutique,” while defending his own Ivy League alma mater, Yale, as not being the same kind of enclave of “liberalism and elitism.” In 2004, George W. Bush’s campaign was able to paint the choice as being between a rugged cowboy type of man who cleared brush on his ranch and a stiff Massachusetts liberal, married to a multi-million dollar ketchup heiress. And a minor flap was created in 2008 when then-candidate Obama asked a crowd in Iowa, “Anybody gone into Whole Foods lately and see what they charge for arugula?” Critics immediately pounced on the question as evidence of Obama being a high-falutin elitist. Or in other words, your classic Genteel Patriarch.

While the Genteel Patriarch has fallen out of favor in America, the Heroic Artisan and Self-Made Man continue to live on as ideals of American manliness. We’ll turn our attention to exploring the Heroic Artisan archetype next time.

Source:

Manhood in America by Michael Kimmel

3 Archetypes of American Manliness Series:

Part I: The Genteel Patriarch

Part II: The Heroic Artisan

Part III: The Self-Made Man