For Henry David Thoreau, the summer of 1854 had brought the onset of a stifling malaise — one that had left him feeling “trivial,” “cheap,” and “unprofitable.” The air was dry, the heat was unending, society was pressing in too close around him, and he missed the intensity with which he had lived during his Walden years. So it was with much relief that he greeted the cool nights that arrived with fall, and took advantage of them by taking long walks in the moonlight. Thoreau already thought of his regular, hours-long daytime walks as akin to heroic pilgrimages in which the crusader reconquered “this Holy Land from the hands of the Infidels,” and he brought a similar questing spirit to his moonlit saunters through the woods.

The enemy here was spirit-suffocating triviality, and Thoreau found his night walks to be potently effective in beating back the scourge. He reveled in the cool dampness and mist, thought about how the same moonlight had fallen on humans stretching back thousands of years, and contemplated the way the darkness aroused one’s primeval instincts and symbolized the human unconscious. He often walked along a river, exulting in the way “The sound of this gurgling water…fills my buckets, overflows my float boards, turns all the machinery of my nature, makes me a flume, a sluice-way to the springs of nature. Thus I am washed; thus I drink and quench my thirst.”

While Thoreau’s nocturnal, sense-heightening walks became a regular occurrence, they never became pedestrian. They were never simply a way to get from point A to point B. Rather, they had a purpose beyond their mere mechanics; they were sacred opportunities to re-create himself.

His walks were rituals, rather than routines.

If your life has been feeling trivial, cheap, and unprofitable, the cure may be taking one of your own daily routines and turning it into a spirit-renewing ritual. How exactly you do that is what we’ll be exploring today.

What’s the Difference Between a Routine and a Ritual?

Both routines and rituals consist of repetitive actions undertaken on a regular basis. But there are a couple important differences between them.

One of the defining elements of ritual is that it lacks a strictly practical relationship between its enacted means and its desired ends. For example, there is no direct, empirical causality between shaking hands and making an acquaintance, throwing one’s graduation cap in the air and closing a chapter in life, or making the sign of the cross and receiving divine grace and strength. All of these rituals have historical, cultural, and theological reasons behind them, but the actions themselves do not have efficacy in the absence of this context. There is a meaning and purpose behind a ritual that transcends its observable components.

Routines, on the other hand, employ means that are practically connected with their ends. When you brush your teeth or drive to work, you’re solely aiming at removing tartar and getting to the office, and the actions involved empirically move you towards these goals. The efficacy of routines lies in the actions themselves. There is no deeper meaning or purpose behind a routine; it’s done for its own sake.

Second, routines can be accomplished without much thought. You may arrive at work with little awareness of how you got there. In some rituals there is a different kind of submersion of self-consciousness as one loses oneself in the act, but oftentimes rituals require not a cessation of cognition, but a heightening of it. The efficacy of a ritual is often found in its exact and undeviating performance. Carrying it out thus requires careful focus and presence of mind.

Because of these differences between a routine and a ritual, each is capable of accomplishing different ends. The result of a routine is external and tangible: clean teeth or a timely arrival at work. The effect of a ritual is inward and transcendent: a centered mind, expanded spirit, or renewed dedication to a goal. A ritual cannot be merely a routine, but as we’ll see, a routine can be turned into a ritual.

What Are the Benefits of Creating Rituals in Your Life?

There’s a lot of resistance to ritual in our modern world — both on the institutional and personal level. Some see rituals as boring and pointless, empty and meaningless, or just plain too much work. Others look askance at rituals as being too superstitious and insufficiently rational.

But there are many reasons to view rituals in a new light — as highly effective ways for enhancing your life on a variety of levels. We’ve previously offered an in-depth exploration of the numerous benefits of rituals, particularly on the institutional level. Let’s today look at those benefits as they apply to creating your own:

Rituals center your mind and build your focus. Much of our life is spent going through the motions of mindless routines, tackling a swarm of endless to-dos, putting out “urgent” fires, and surfing from website to website and social media feed to social media feed in a spaced-out haze. Rituals bring you back to the present moment, renewing your awareness of that which is before you, and directing your focus to certain objects, physical sensations, and thoughts. You must concentrate on what you’re doing, and act with care and deliberation.

Set rituals not only quiet the daily frenzy of your mind, but can also help carry you through times when greater irruptions have burst upon your life. A morning shaving ritual, for example, can become a salve — a single daily pocket of calm and centering — in an otherwise grief-stricken or stressful period.

The exercise your focus receives from engaging in ritual will extend out to other areas of your life as well, improving your attention span for other tasks that require keen concentration. In his forthcoming book, Deep Work, professor Calvin Newport notes that many famous men used rituals as preparation for immersive work sessions: “Their rituals minimized the friction in this transition to depth, allowing them to go deep more easily and stay in the state longer.”

Rituals encourage embodiment. In the digital age, we can often feel like disembodied non-beings, floating around untethered to reality. Because physicality is one of the essential components of ritual, it counteracts these feelings by encouraging greater embodiment and renewing our connection with the tangible world.

For example, primitive people had many hunting-related rituals — pre-hunt rituals to increase chances of bagging game, rituals for how to kill the animals, rituals for how to cut them up and handle the corpse, and rituals for how to eat the meat. Such rituals connected them to the rhythms of life and death. Today, we wolf down our food without even tasting it. We’re disconnected from the process of how we obtain and consume our sustenance, and this can have detrimental effects on our health. Rituals — such as saying grace before a meal or making coffee with a French press — can help us slow down and connect with what we are doing in the moment, reorienting our bodies in time and space.

The greater sense of embodiment encouraged by ritual isn’t only beneficial in and of itself, but also enhances the effectiveness of the intended act. Making certain movements and putting your body in certain physical positions can change the way you feel and alter your mindset. For example, if you wish to lose yourself in fervent prayer, kneeling will immediately make you feel more reverent and humble than lying in bed. Similarly, walking can often spur your thinking in a way that sitting at a desk does not.

Rituals invite special powers and inspiration. While we often feel that inspiration is a mysterious, spontaneous force we must wait around for, it can in fact be coaxed into paying us a visit. In fact, strict consistency has proven time and again to be a greater enticement to the muses than irregularity. Special forces of mind and spirit flow better through a controlled conduit — or in other words, a ritual.

A perfect example of this are the various rituals many writers perform before they get down to work in hopes of priming their minds for inspiration. Some brew a fresh pot of strong coffee, go for a walk, or clear their desk of everything but their laptop. In The War of Art, author Steven Pressfield describes the pre-writing ritual he uses to prepare his mind to overcome what he calls “The Resistance”:

“I get up, take a shower, have breakfast. I read the paper, brush my teeth. If I have phone calls to make, I make them. I’ve got my coffee now. I put on my lucky work boots and stitch up the lucky laces that my niece Meredith gave me. I head back to my office, crank up the computer. My lucky hooded sweatshirt is draped over the chair, with the lucky charm I got from a gypsy in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer for only eight bucks in francs, and my lucky LARGO name tag that came from a dream I once had. I put it on. On my thesaurus is my lucky cannon that my friend Bob Versandi gave me from Morro Castle, Cuba. I point it toward my chair, so it can fire inspiration into me. I say my prayer, which is the Invocation of the Muse from Homer’s Odyssey, translation by T.E. Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia, that my dear mate Paul Rink gave me and which sits near my shelf with the cuff links that belonged to my father and my lucky acorn from the battlefield at Thermopylae. It’s about ten-thirty now. I sit down and plunge in.”

Do Pressfield’s invocations and various totems actually extort a force on his writing? Far be it for me to rule it out, but much of their power lies in the way they prepare his mind for the task ahead. Going through the steps of the ritual enhances his receptivity to inspiration, and any other mysterious forces and powers that may be hanging around his office.

Rituals create sacred time and space. Religion historian Mircea Eliade made famous the idea that there are essentially “two modes of being in the world”: the sacred and the profane. The profane constitutes our natural, secular lives, while the sacred represents fascinating and awe-inspiring mystery — a “manifestation of a wholly different order.”

In a traditional society, all of man’s vital functions not only had a practical purpose but could also potentially be transfigured into something charged with sacredness. Everything from eating to sex to work could “become a sacrament, that is, a communion with the sacred.” In the modern, thoroughly profane world, such activities have been desacralized and disenchanted.

The creation of personal rituals can help you revive some of that enchantment in your life. And it isn’t just something for the religious to seek. Even if you wouldn’t term it the “sacred,” we all crave moments of deeper significance — moments that are special and extra-ordinary and open an insight into the greater meaning of things. Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly, the authors of All Things Shining, call this experience in which “the most real things in the world present themselves to us” a “whooshing up.”

In creating the circumstances by which we become more receptive to extra-ordinary feelings and inspiration, rituals can help more of life whoosh up to us. As Eliade puts it, rituals allow participants to “separate themselves, partially if not totally, from the roles and statuses they have in the workaday world” and cross a “threshold in time and space or both.” In this they add not only more mystery and magic to one’s life, but also a greater feeling of texture. When the landscape of one’s existence consists of an unbroken expanse of the profane, life can feel flat and one-dimensional. Rituals allow us to move between the ordinary and the sacred, opening up richer dimensions of experience.

How Do You Know If a Routine Can Be Turned Into a Ritual?

That might all sound very heady, as we’re used to thinking of sacred, centering, inspiration-inviting things in conjunction with big, dramatic, religious institutions or more formal spiritual practices. But rituals neither have to be attached to existing organizations nor pulled whole cloth from thin air. They can truly be created out of the most prosaic material, including your already existing daily routines. There are things you do right now each day, that, with some tinkering and greater intention, can be turned into powerful personal rituals.

But not every routine is equally conducive to this transformation. So how do you know if one has the potential to be ritualized? Remember, a ritual has a purpose above and beyond what the mechanics of the routine itself accomplish. The task then is to figure out which of your routines already contain a latent significance that you have previously ignored. Or as Dreyfus and Kelly put it: “The project…is not to decide what to care about, but to discover what it is about which one already cares.” Using the example of deciding whether one’s daily coffee drinking routine might be turned into something more, they offer some guidelines for thinking through the question:

“One cannot expect every moment of one’s existence to be a sacred celebration of meaning and worth. Indeed, there is probably something about us that resists this or even makes it impossible. But to endure the absence of meaning is one thing, to embrace it another. If we are to be human beings at all, we must distinguish ourselves from others; there must be moments when we rise up out of the generic and banal and into the particular and skillfully engaged. But how is one to know whether the coffee-drinking ritual is one of these moments?

The answer is that one must learn and see. That you already care about coffee drinking is something you may have hidden from yourself. To find out whether this is so, ask whether you take the routine to be functionally exchangeable. The morning ritual is delightful in part because it wakes you up. But would anything that woke you up be equally good? Would a quick snort of cocaine substitute in a pinch? Or if that’s too extreme, then perhaps a small caffeine pill that one could swallow on the way to the car? To the extent that these exchanges seem appealing, then the coffee really is just performing the function of waking you up. In that case any form of stimulant would do. But to the extent that these do not seem like appealing substitutes, there are aspects of the coffee-drinking ritual that go beyond its function, aspects about which you already care.”

Think about the daily routines you already perform: getting ready in the morning, having breakfast, working out, reading in the evening, and so on. Identify those in which you could substitute other actions that are functionally equivalent without feeling much loss. Perhaps you shave with a safety razor, but wouldn’t care about switching to the cartridge variety; shaving is just a routine for you. Now think about routines where switching out some of the elements would make a difference. Maybe you’re a runner, and while you could get the same cardiovascular benefits from doing the elliptical machine, you would never think of trading one exercise for the other. Because you care about your daily run in a way that transcends its simple utility, it has the potential to be turned from a routine into a ritual.

How Do You Turn a Routine Into a Ritual?

Once you’ve identified a routine to which you already lend a deeper meaning and purpose beyond its mere functionality, the next step is to tinker with its components in order to heighten its significance and transform it into a genuine ritual.

As Dreyfus and Kelly explain by retuning to the coffee drinking example, you do this by first uncovering the aspects of the routine that are not interchangeable and that are meaningful for you, and then deliberately enhancing those elements:

“The clue to revealing these distinctions lies in further simple questions you must ask yourself. Why exactly do you prefer a cup of coffee to a caffeine pill or to a cup of tea? Is there something in the coffee itself, not just in its stimulating effect but in its aroma, its warmth, the ritual of drinking it, or something else—that drives you to this activity rather than some other? And to the extent that there is, then what kind of coffee-making process, what kind of coffee-drinking companions or coffee-drinking places, what kind of coffee cup would bring these things out best?

These are not questions you can answer in the abstract. You need to try it out and see. If it is the warmth of the coffee on a winter’s day that you like, then drinking in a cozy corner of the house, perhaps by the fire with a blanket, in a cup that transmits the warmth to your hands might well help to bring out the best of this ritual. If it is the striking black color of the coffee that attracts your eye and enhances the aroma, then perhaps a cup with a shiny white interior will bring this out. But there is no single answer to the question of what makes the ritual appealing, and it takes experimentation and observation, with its risks and rewards, to discover the meaningful distinctions yourself.”

As you think through the elements of your routine that could be enhanced to turn it into a ritual, consider what you might tweak in these categories:

Location & Atmosphere. There’s a reason most religions ask their adherents to practice their faith not only in private, but also in houses of worship. Part of it is to gather in community. But it’s also because of the fact that changing one’s physical space can alter one’s perspective and prepare the mind to go deeper in worship.

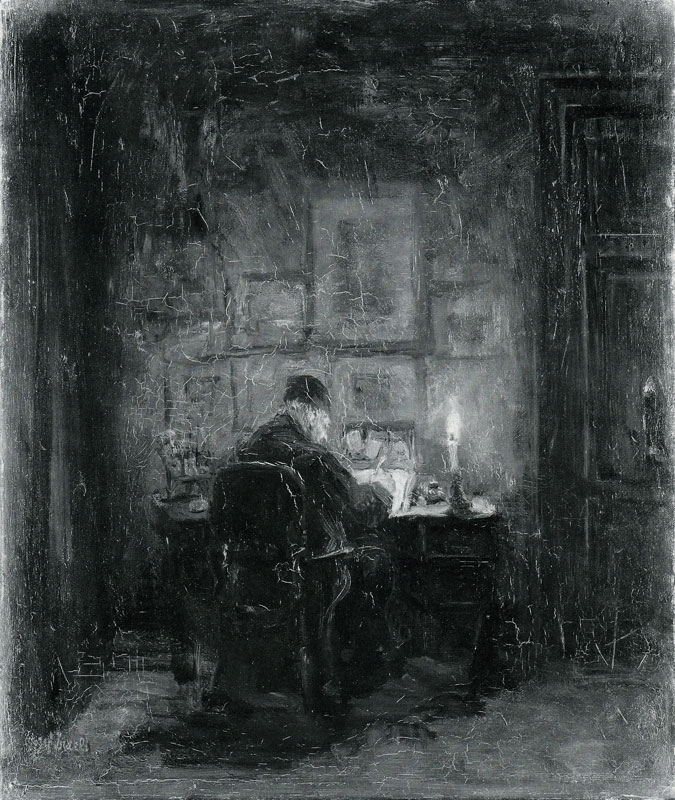

Similarly, intentionally creating sacred space can symbolically help you cross a threshold out of your ordinary life and elevate your personal rituals. Reading on the couch while your wife watches TV is unlikely to feel like a meditative ritual, while reading in a quiet alcove of the house, lit only by a kerosene lantern, likely will.

Sacred space need not be enclosed inside four walls either; if you’ve decided that fresh air and a sense of physical freedom are some of the meaningful distinctions about your running routine that cause you to choose it over the elliptical machine, heighten those elements by not only doing more of your running outside, but moving off the asphalt trails and into the woods.

Objects. We have a tendency to be dismissive of the physical world, writing off all objects as mere “stuff.” But objects — from candles to clothing — have been important elements of spiritual rituals the world over. For they act as extensions of the embodiment of ritual — tools that can greatly enhance the experience. So take the objects involved in your daily routine seriously, and consider how tinkering with them might help you better tap into the deeper meaning you’re seeking in the task.

Take journaling, for example. It might sound silly that swapping out your BIC pen and spiral notebook could turn the routine into a ritual, but it works. If your motivation for journaling is to pass on a record of your life to future generations, then writing in a handsome leather-bound journal — something you can see your great-grandchildren leafing through one day — may help heighten the significance you feel in the task. Or if you journal in hopes of sorting through the thoughts in your head, writing with a fountain pen may improve your feeling of flow.

Shaving is another example where it’s easy to see the difference objects can make in turning a routine into a ritual. If shaving is about more than removing your stubble each morning, and is rather a time you use to get your mind centered for the day to come, you might consider using a safety razor over a cartridge, as it forces you to slow down and concentrate on what you’re doing. And using not just any safety razor, but your grandfather’s, may further serve as a daily reminder to become a strong link in your family’s generations of men.

Timing. There are some routines that may seem more meaningful to you when you do them at certain times of the day. Taking a walk in the morning may seem rather pedestrian, while walking at night may feel a little magical and mysterious. Conversely, shining your shoes may feel like a burdensome chore at night, but a mind-calming ritual in the morning. There are ambient elements present at different times during the day that may work for or against your mood and the greater purpose behind your routine.

Mindset. A big part of what elevates an activity beyond the merely mechanical is what it does for your mindset. And a big part of turning a routine into a ritual is finding ways to heighten this effect. If you value your daily walk for the opportunity it gives you for thinking through knotty problems and receiving insights, prime the pump for inspiration by reading something meaty and thought-provoking before you step out the door. Similarly, if part of why you take cold showers is the feeling of greater grit and resilience they give you, strengthen this confidence boost by reading a passage from Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations right before you disrobe.

The more of the above elements you work to enhance, the more ritualistic your routines will become. Read some Thoreau right before going for a run in the woods. Listen to classical music as you shave with your safety razor. Journal with your fountain pen in the morning in your sunroom. Read your scriptures at night by candlelight with a warm mug of tea. By seeking to turn your ordinary routines into spirit-renewing rituals, you can elevate your ho-hum life into one embedded with greater meaning, purpose, and enchantment.

Listen to our podcast with William Ayot on a man’s need for ritual: