Come! Enter a banquet hall of the early Middle Ages and sit down to enjoy some dinner. At one end of the table is a whole spit-roasted pig, which seems to be looking at you funny. At the other end are a few game birds, their feathers still intact. Your dining companions sniff at the platters and snort in approval.

The host carves up the meat and passes it down. Each man holds a knife (his only utensil) in one hand and grabs a piece of meat with his other, stuffing it in his face and chewing with his mouth open. After gnawing and sampling the piece for a bit, if he doesn’t find it to his liking, he returns the cut to the platter for someone else to try.

Soup is passed around in a communal bowl, and you can either drink it right from the vessel, or use the single spoon available to slurp it up. A communal goblet of wine is also passed around which you’re welcome to sip on when it’s your turn.

The dining companion on your right occasionally pauses from eating and passing you food to blow his nose in his fingers and wipe his greasy, snotty hands on his shirt. The man to your left periodically spits across the table. The hall is filled with many noises — not only the snorting, slurping, spitting, blowing, and chewing — but also the sound of numerous and uninhibited belches and farts.

Bones and gristle are tossed on the floor, which has been covered in clay and a layer of rush plants. The rushes are supposed to be changed out regularly, but most, like this host, don’t keep up with it, and mixed into the plants are a fine patina of food scraps, vomit, spit, and dog urine. Human urine is scattered here and there as well — the host prefers you’d do your business outside the hall, but it’s not a big deal to relieve yourself in a dark corner.

***

In the modern day, we’re apt to see such a scene as a little embarrassing if not objectively disgusting.

By why exactly? What changed over the centuries in the West to make eating like that unthinkable?

You might initially think it has to do with a greater understanding of hygiene. But table manners began changing even during the Middle Ages, and much of what we consider modern dining etiquette was established by the time of the Renaissance — well before the connection between germs and disease was really understood. Indeed, hygiene would not be forwarded as a rationale for table manners until the 18th century; by then it was simply used as a retrospective justification that bolstered the validity of a set of already adopted manners.

If one actually thinks about how we dine in the modern age, much of the hygiene argument falls apart; even though we eat most solid foods like meat with a fork, we still grab other foods, like rolls, with our fingers. Had table manners developed primarily to cut down on the exchange of germs, we’d be hitting our cupcakes with a knife and fork and eating tortilla chips with tiny tongs.

The truth is that we now simply find things like grabbing meat with your hands, or chewing with your mouth open, or farting at the table, distasteful. Such behaviors feel gross to you and look gross to other people.

And the question again is why. Why do we find certain things gross that our medieval counterparts didn’t bat an eye at?

What was it that created what sociologist Norbert Elias called “an advance in the threshold of repugnance and the frontier of shame”?

You’ve likely never stopped to think about it — it seems like an inevitability that manners would become more refined as a society advanced economically, scientifically, and politically.

Yet the development of manners wasn’t simply a byproduct of these advancements, but was in fact an essential and necessary prerequisite to them.

In many ways, manners made the world.

The Courtly Origins of Courtesy

In The Civilizing Process, Elias traces the nucleus of Western manners to the courts of feudal Europe during the Middle Ages.

As roaming, armed bands conquered more fiefdoms, consolidated their territory, and settled in to rule their holdings, power came to reside in the courts of kings and local magnates. Warriors became courtiers, and status was earned less through physical combat than the shrewd navigation of the court’s social landscape. Words took the place of weapons, as the nobility sought to curry the king’s favor, form alliances, ward off would-be rivals, and rise in the royal household.

Doing so demanded a new kind of orientation to the world and to others; the courts could be full of intrigues, backstabbing, and cutthroat manipulations, and a courtier needed to closely monitor his own behavior and the behavior of others, interpreting people’s motives and anticipating the consequences of making certain moves. He had to maintain constant awareness of his status relative to others — whether he was up or down, what his fellow nobles thought of him, and how much influence he did or did not have. A single misstep — saying the wrong thing, giving the wrong look, allying with the wrong person — could bring down his value. A courtier had to be sensitive to the needs and inclinations of others and careful to react properly and not offend; deft social conduct was his greatest asset.

It is from aristocratic court life that we get the pithy, surprisingly modern maxims on behavior offered by French nobleman Francois de la Rochefoucauld and the Jesuit priest Baltasar Gracian. It’s also where we get our word courtesy — which basically meant “the manners of the court†or “how to behave at court.â€

Courtesy was not only a code of behavior that helped the landed aristocracy gain and maintain status and influence, it was a way of distinguishing their whole class from the bourgeoisie and the peasants below them. Nobility, who didn’t have to work to earn a living, had the time to refine their taste and manners, and the way they talked, walked, dressed, and ate, separated them as the elite and gave them a special identity. Their refinement set them apart from all that was “vulgar†— i.e., common.

Courtesy Becomes Civility: Manners Move Down (And Up)

An interest in manners greatly expanded during the Renaissance, as merchants, clerics, and other emerging professionals slowly began to form a nascent middle-class. This tier of society began to mix a little more with the landed aristocrats, and while the nobility knew how to demonstrate courtesy from lived experience, the bourgeoisie had to intentionally study and practice their courtly manners. Thus, etiquette books proliferated during this time as self-help manuals for middle-class strivers who wished to be able to visit court and mix comfortably with their social betters. Schools and tutors adopted such texts to help children learn the conduct necessary for rising in the world and getting ahead.

As courtesy began to be more democratized, it started to be called civility — the proper conduct for all citizens to embrace. The democratization of manners also led to their further and further refinement. Etiquette had started as a status symbol of the nobility, but as the middle-class began to adopt its code as well, the old manners lost their prestige and value as a marker of class identity. So aristocrats refined their manners further, in order to continue to distinguish themselves from commoners. But of course, in time the common people simply came to imitate those newly refined manners too, forcing the nobility to refine theirs even further. And on the cycle went, until both the upper and middle classes lived an elaborate and detailed set of rules for their conduct.

While the movement of manners was generally from the top down, it sometimes worked the other way round, especially during the Victorian Age. Reform bills during this period expanded the franchise to millions more men, creating a greater sense of egalitarianism and fostering the idea that gentility (which had referred to one’s noble birth), and the title of “gentleman,†could transcend class. In fact, middle-class gents perceived themselves to be the leaders of virtue and etiquette — examples to the aristocracy, which they perceived as having become vain, decadent, frivolous, and foppish.

Middle-class Victorians strove for more soberness and rectitude than their aristocratic peers, particularly in demonstrating modesty in matters of money and sexual morality. Much of etiquette came to center on that which is needful in a productive economy (e.g. punctuality), and while the aristocracy had formerly prided themselves on their disdain for labor and love of leisure, doing some kind of work, whether charitable or profit-seeking, became a central component of respectability for the rich and poor alike. Thus, upper-class manners moved down, and middle-class mores moved up, so that the culture of etiquette became a melding of the two, and eventually trickled down to the lowest classes as well.

From Fingers to Handkerchiefs: Examples of the Advancing Standards of Etiquette

If we look at a few examples of what exactly the refinement of manners and the “advance in the threshold of repugnance†looked like in some different areas of behavior, we can get a better grasp of how manners fundamentally re-shaped the social structure of Western society.

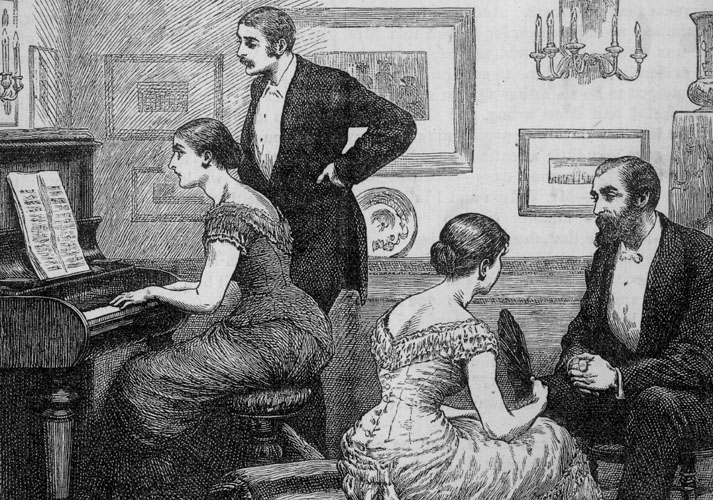

The evolution of table manners is one of the most evident cases. Up until the 17th century, forks were essentially a luxury item; made of silver or gold, they were a status symbol reserved for the upper class. But as the centuries progressed, and forks became de rigueur for the lower classes as well, the rich upped their dining game, and developed special utensils for each dish — salad fork, dinner fork, dessert fork; soup spoon, teaspoon, dessert spoon; dinner knife, bread knife, etc. And all the utensils were to be placed on a certain side of your plate and used only during the appropriate part of the meal. Of course special plates, napkins, glasses, and an assortment of other refined details and rules were added as well.

In modern times, all these accouterments are only used in formal dining settings, but the way in which upper class manners trickled down and proliferated all tiers of society remains indelible: today everyone considers it gauche to eat most solid foods with one’s fingers and uses a set of at least several utensils to eat their meals.

The refinement of manners centered not just on eating, but all other bodily functions as well.

In the 16th century, for example, how one blew one’s nose broke down by class lines, as the social critic and etiquette book author Erasmus observed: “the common people blow their noses without a handkerchief, but among the bourgeoisie it is accepted practice to use the sleeves. As for the rich, they carry a handkerchief in their pockets; therefore, to say that a man has wealth, one says that he does not blow his nose on his sleeve.”

Handkerchiefs became more and more popular as the centuries progressed, and additional rules were developed, like not looking into your hankie after blowing to see what had come out of your nose. These days, a great many men find even the idea of blowing your nose into a reusable handkerchief disgusting, and insist upon the use of disposable tissues.

Medieval toilets, called garderobes, typically consisted simply of a bench and a hole that connected to a chute. Waste dropped into a moat or cesspool below. As one can see, citizens of the Middle Ages had less concerns about privacy than we moderns.

Then there was the etiquette of waste elimination. In the early Middle Ages, people urinated and defecated over outdoor pits, and even when buildings had dedicated areas in which to do one’s business whilst indoors, folks sometimes relieved themselves in closets, hallways, and staircases anyway. It was also considered perfectly acceptable for men and women to see each other going the bathroom, and to greet and talk to folks while they were pooping and peeing.

People were way more comfortable handling and sniffing their excrement as well. In 1558, the poet and etiquette author Giovanni della Casa felt it necessary to lay out this rule for going #2: “It is far less proper to hold out the stinking thing for the other to smell, as some are wont, who even urge the other to do so, lifting the foul-smelling thing to his nostrils and saying, ‘I should like to know how much that stinks,’ when it would be better to say, ‘Because it stinks do not smell it.’â€

By the 18th century, etiquette books said that if you came upon someone doing their business, you should pretend not to see them. And asking others to smell your feces was definitely out. Communal toilets in the outdoors evolved into indoor throne rooms and public, lockable stalls where you could take care of business in complete privacy.

Even the etiquette of farting underwent distinct phases of development. Passing gas in public warranted no attention in the early Middle Ages, as it was considered unhealthy to hold it in. By the 16th century, some farting proscriptions began to emerge, mainly that you should try to release your gas as quietly as possible, squeezing your butt cheeks together to suppress it if necessary. If a noisy toot could not be avoided, Erasmus’ advice was to “Let a cough hide the explosive sound.†But by 1729, another etiquette expert superseded that guideline, intoning that “It is very impolite to emit wind from your body when in company…even if it is done without noise.” Silent or not, the time for the public passing of gas had passed.

Today of course, etiquette books don’t even mention farting at all — it would be too crass to even discuss, and the author takes for granted the fact that the reader would never pass gas around others under any circumstances. Not even if timed with a cough.

Advancements in the refinement of manners and the threshold of repugnance didn’t just occur in areas of human life that concern bodily functions, of course. People became not only more easily grossed out when it came to things like eating or defecating, but also had a higher threshold for that which offended in social exchanges. Rules developed regarding speech, conversation, clothing, courting, parties, work, sportsmanship…anything that involved human interactions.

All of these increasingly detailed and strict codes of conduct had a few things in common. First, they moved anything considered distasteful and/or animal-like behind the scenes. Second, they created greater space, distance, and privacy between individuals. Third, they required that people restrain their natural impulses and exercise greater sensitivity to the feelings of others. To meet these requirements in order for their behavior not to offend, or bring shame, people had to develop a higher and higher degree of personal discipline and self-control.

But Why?

So we’ve discussed where manners came from, and how they spread, but we still haven’t really answered the question of why. Why did a culture of manners arise when it did and why did it win such widespread and vigorous acceptance?

Sure, it’s natural for lower status folks to imitate higher status folks, so it makes sense that the middle class was eager to adopt the mores of the upper. But why did a culture of courtesy become as pervasive and ultimately enduring as it did? After all, European aristocrats engaged in all sorts of practices, like, say, wearing codpieces, that never caught on with the masses. And even given that it makes sense for the lower classes to fall in line with their social betters, why would the upper classes have ever deigned to practice their manners with the common people?

The answer is that the economic/political/scientific changes to the structure of society that began to arise from the Middle Ages onward, necessitated a change in society’s emotional/social structure.

Up until the Middle Ages, people led relatively independent lives. The poor were bound to their lords, but made, grew, or bartered for all that they needed. Lords provided for themselves from their land, and could get anything they lacked simply by using force and riding roughshod over the weaker.

Neither class thus had to worry much about offending their peers. So what if a peasant’s friends were grossed out by something he did? In truth, folks didn’t really think in terms of being grossed out by other people’s behaviors at all, as it just wasn’t how they related to each other and structured their interactions. Their greatest “social fear†was to be physically attacked and defeated/humiliated/tortured/enslaved by a rival.

For this reason, people of all classes could afford to be volatile with their emotions and impulsive in their behaviors. Feelings were given freer reign, were released more spontaneously, and swung between greater extremes. Life was so uncertain that people lived more in the moment, acting without regard to future consequences. You fully embraced whatever inclinations you were experiencing at the time.

But as ruling power was consolidated into fewer hands, and more stable governments were formed, people began to be connected in more and more intimate ways, and a new emotional/social landscape became necessary.

The right to exercise physical force became reserved for those legitimized by the central authority (army/police), which made the chances of encountering violence increasingly rare and calculable. More and more pockets of security and stability were formed. Within these pockets, population, productivity, living standards, and labor specialization went up. As a result, members of society became more and more interdependent. The longer and more complex the chains of connection that developed between individuals, the more the “civilizing process†— the march of manners — took hold.

The more a population increased in density, the greater the division in labor, and the deeper the interdependence of society grew, the more people had to be aware of the sensibilities of others — giving people enough space and privacy, being careful not to offend, monitoring moods, and anticipating reactions.

The fear of physical attack was replaced with the fear of embarrassing oneself in front of others, and right social conduct became a form of weaponry and currency. The fight for status and success was no longer carried out on the battlefield but in the realms of politics, economics, academia, and most of all, within oneself. Behavior was not checked by external force but internal control, and victory — the chance to rise in the world and achieve one’s aims — went to the man with the greatest self-mastery.

From Courtesy to Civility to Civilization: Why Manners Are an Essential Analogue to Democracy

In an interdependent society, all classes are forced to treat each other with at least a basic level of respect.

While courtesy began as a high falutin code of behavior that dictated how lower status individuals should act towards higher status ones, and how higher status individuals were to act with one another, it ultimately became a set of manners all classes were expected to follow, regardless of whom they were interacting with. For example, a nobleman of the Renaissance could only feel shame in violating the sensibilities of his equal. So while one courtier wouldn’t have passed gas in front of another, he would have felt no compunction in doing so in front of a servant. But as courtesy became civility, the upper classes came to feel bound to restrain their behavior amongst all classes and became capable of feeling shame even in the presence of their social inferiors; a rich man of the 19th century wouldn’t have farted in an elevator even if only he and the elevator operator were present.

In a pre-civilized culture, might makes right and independent bands of the strong can treat the weak with impunity. But in a civilized culture, where only a few are authorized to exercise violence, you can’t bludgeon someone in the head when they annoy you, or egregiously trample over their rights. Even if you’re rich, strong, and powerful, you rely on a doctor, trash man, electrician, mechanic, etc., as well as a slew of consumer goods made by factory workers, for your life to function. Such folks aren’t your slaves or indentured serfs, so you can’t be completely rude to them and expect them to do whatever you want. They’ve got power now too; the power to walk away from an economic transaction.

So while the rich and powerful always maintain unique etiquette rules that set them apart as elite, the existence of a universal code of basic manners acts as something of a social leveler.

But establishing a code of conduct that applied to all wasn’t the only or most important way manners forwarded democracy: the practice of etiquette also developed the qualities necessary to the flourishing of that type of government.

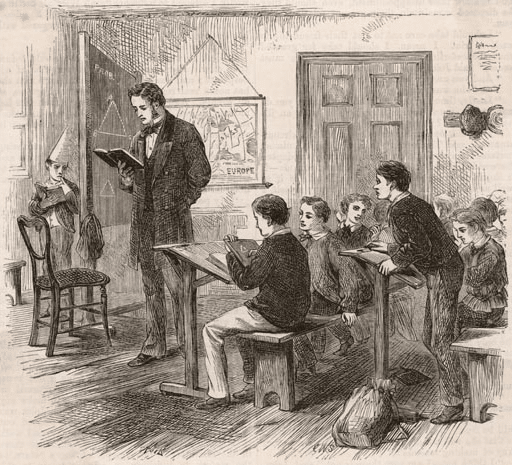

For citizens to be fully engaged, they must be literate, and to become literate, and gain the skills necessary for critical thinking, they must have the discipline to slowly learn how to understand harder and harder texts.

For free market enterprises and government bodies to function and thrive, people need to act in stable and predictable ways and be able to exercise hindsight, foresight, and delayed gratification. They must be able to forward diplomacy instead of insults and violence. They must be able to put aside short-term impulses and plan for long-term goals.

Manners are essentially practices for these skills and qualities — ways to build your foresight and self-control each day. They force you to reflect and look ahead, predicting what kind of behavior will garner what kind of consequences. They make you put your short-term inclinations to the side sometimes: instead of interrupting someone in conversation, you wait your turn to speak; instead of dressing in sweat pants for a wedding, you put on your best suit; instead of demanding or grabbing food, you pause to say please; instead of always acting on impulses, you learn to master them.

In short, individual self-control is the price of democracy, and practicing manners is central to the development of this quality. Manners thus provided the scaffolding that helped move Western society from courtesy, to civility, to civilization.

Or in other words, manners made the modern world.

If Manners Made the World, Could Boorishness Undo It?

Did a code of manners create the possibility for democratic, capitalist systems, or did a capitalist, democratic system create the possibility for a culture of manners? It’s a chicken and egg question, and the truth is that they fed back and reinforced each other. Democratic systems help create stable and secure environments where the risk of violence is rare and calculable, and manners can afford to be practiced; people don’t have the space and willpower to concentrate on chewing with their mouths closed and what to wear to a wedding when they live in a world of danger and chaos. But even in a secure environment, people can’t carry out their 9-5 jobs and become involved citizens when they aren’t able to practice self-control and delayed gratification.

Both ingredients are necessary for the system to flourish.

And that brings up an interesting question: if manners made the modern world, then could the cycle be run in reverse — could their disappearance undo it, eventually bringing us back to a more medieval society?

In the Middle Ages there wasn’t much emotional/behavioral distance between children and adults; the young and old wore similar clothes, talked in a similar way, did similar things, and had a similar level of intelligence. Children were more adult-like than they are now, and adults were more child-like.

With the invention of the printing press, and other scientific, political, and economic advances, childhood was transformed into a prolonged and distinct period of life. This was done to give children a training period in which to learn the discipline and self-control they would need to grasp increasingly difficult books, study math and art, debate policies, and so on. A key part of this training was learning manners — learning to master their impulses instead of letting their impulses master them. The self-control they learned by practicing manners then carried over into all aspects of their lives. Step by step, this training initiated them into the “secret society of adults†in which they could take their places as the world’s future analytical scientists, shrewd businessmen, level-headed politicians, disciplined writers, and so on.

Today when people wring their hands about grownups acting no better than children, there’s a deeper concern behind the worry than simply being sad to see the degradation of past traditions.

There’s a concern, even if subconscious, that the failure to say please and thank you just might loosen the threads of civilization itself, and leave us with no steady captains who are ready to step up and pilot the ship.

And it’s not such a crazy thing to worry about after all.

Conclusion: Barbarians at the Gate, or the Possibility of a Manners Tipping Point

We humans are funny about restraints on our behavior. On the one hand, we know that some rules and disciplines can actually enhance our liberty — roads and traffic laws help us get where we’re going; grinding it out at the gym keeps us healthy.

But on the other hand, we all have the desire to chuck it all and be able to do whatever we want, where we want, how we want. We want to run that red light sometimes, and only eat burgers and fries on the couch.

So it is with manners. Sometimes we just want to let it all hang out and forget about all these sometimes seemingly pointless and fuddy duddy rules for social interaction. Haven’t things loosened up in the modern day without there being dire consequences?

What we fail to realize is that this loosening has occurred within a structure of an already well-established system of self-control that’s easy to take for granted. Elias explains it well:

“The freedom and lack of inhibition with which people say what has to be said without embarrassment, without the forced smile and laughter of a taboo infringement…is only possible because the level of habitual, technically and institutionally consolidated self-control, the individual capacity to restrain one’s urges and behavior in correspondence with the more advanced feelings for what is offensive, has been on the whole secured. It is a relaxation within the framework of an already established standard [emphasis mine].”

While it may be fun and entertaining to flirt with a little more chaos, to break, or watch others break, the old fashioned rules of civility and respect, to indulge in a fantasy about a return to barbarianism (in which you’re always on the strong, winning side, never on the humiliated, tortured, enslaved side), one wonders if at a certain point all this loosening up would eventually compromise the integrity of the foundation of self-control that’s been centuries in the building.

That is, is it possible we could reach a manners tipping point?

If those with high status show disdain for manners, and their dismissal isn’t linked to a lack of success; if peers don’t exert pressure on each other to keep the code; if parents don’t teach their children etiquette from a young age; if people stop getting daily training in self-control, could this lack of regular practice and reinforcement contribute to the diminishment of citizens’ discipline in all areas of their lives? Might people in a world of atrophied manners start to have a more difficult time holding in their road rage, staying faithful to their spouse, and reading and discussing hard books/articles/news? And if people lose the ability to digest nuanced information, and thus can’t engage intelligently in the political process, could President Camacho be voted into office, and society regress its way back to the Dark Ages (now airing episodes of Ow My Balls)?

Please discuss.