Nine years ago, business authors Jim Collins and Morten T. Hansen, along with a team of 20 researchers, set out to answer this question: Why do some companies thrive in uncertainty, even chaos, and others do not?

The group analyzed seven companies that performed not just better than their industry, but ten times better. They discovered a very interesting key finding. The qualities that business gurus frequently tout as being the main difference-makers — things like innovation, creativity, and the ability to quickly pivot in a fast-changing world – were indeed somewhat important, but it was actually discipline, fanatic discipline, that was one of the true master keys of the companies’ success.

Instead of constantly changing course, making really aggressive moves, and taking big risks, “10Xers” (as Collins and Hansen dubbed these greatly successful companies) came up with a plan, and carefully, methodically, and consistently stuck with that plan; they moved ever towards their long-term goals instead of getting side-tracked by short-term temptations, fears, and changing circumstances. They didn’t panic during stormy periods, nor did they expand too aggressively during good times.

For example, Southwest Airlines made it a goal to create a different kind of company culture, and turn a profit every single year. While the airline industry as a whole lost money during the recession, and other airlines axed employees and lost piles of cash, Southwest achieved their goal, keeping themselves in the black for 30 consecutive years without ever having to furlough a single employee. As Collins and Hansen explain in the book that emerged from their research on 10X companies, Great by Choice, Southwest did it through careful, consistent growth:

“Southwest had the discipline to hold back in good times so as not to extend beyond its ability to preserve profitability and the Southwest culture. It didn’t expand outside Texas until nearly eight years after starting service, making a small jump to New Orleans. Southwest moved outward from Texas in deliberate steps — Oklahoma City, Tulsa, Albuquerque, Phoenix, Los Angeles — and didn’t reach the eastern seaboard until almost a quarter of a century after its funding. In 1996, more than a hundred cities clamored for Southwest service. And how many cities did Southwest open that year? Four.”

The 20 Mile March

Collins and Morten dubbed the slow and steady approach taken by Southwest and other 10X companies “The 20 Mile March.” They took this moniker from imagining a man determined to walk across the United States, and how he could accomplish his goal faster by committing to walking 20 miles every single day — rain or shine — rather than walking for 40-50 miles in good weather and then very few miles or not at all during inclement conditions.

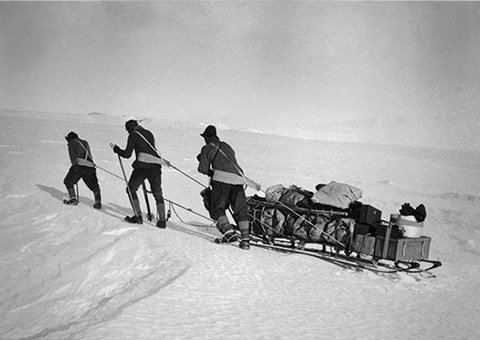

The pair later came upon the story of the race between Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen to be the first to reach the South Pole, and they were amazed to discover how the differences in the way the two expeditions were executed also aligned with their 20 Mile March idea. Amundsen beat Scott to the Pole and had a pretty smooth and uneventful journey both there and back. Scott reached the Pole only to face the crushing realization that the Norwegians had been there first, and he and his four men perished on the grueling 700-mile return trip. Collins and Hansen found that among the many other lessons comparing the two expeditions can teach us, is that much of Amundsen’s success can be traced to creating his own plan, and then carrying it out with methodical, disciplined consistency. In other words, sticking with his 20 Mile March.

Your 20 Mile March

As I read Great by Choice, I was struck by how applicable the 20 Mile March principle was not simply to corporations or polar expeditions, but to individual lives as well. Many of the men I see struggling to improve themselves usually tackle their goals through an inevitably fruitless series of fits and starts. They get all excited about a new goal or program for themselves and throw themselves into it with gusto, only to soon get burned out, sidetracked by the next cool new thing, or demoralized by a setback. This pattern leaves an unending trail of unfinished projects in their wake.

I completely sympathize with these gents, because I’ve done that too! But as I evaluate the times I’ve been successful in life, I notice a pattern. It usually wasn’t through big Herculean efforts, or snazzy new productivity plans that I achieved my goals, but rather through steady, consistent efforts. I reached my goals by throwing on my knapsack every single day and setting off on a 20 Mile March.

The Seven Elements of a Good 20 Mile March

In the book, Collins and Morten lay out seven elements that create a good 20 Mile March:

- Clear performance markers

- Self-imposed constraints

- Appropriate to the enterprise [or individual]

- Largely within your control

- A proper timeframe — long enough to manage, yet short enough to have teeth

- Designed and self-imposed by the enterprise [or individual]

- Achieved with high consistency

Below we take a look at each of these elements one-by-one. Because I think it’s so instructive, we’ll first take a look at how each of these elements played out in the race to the South Pole. We’ll then explore how we can apply these elements in our own lives to create our own 20 Mile Marches.

1. A good 20 Mile March uses performance markers that delineate a lower bound of acceptable achievement. These create productive discomfort…and must be challenging (but not impossible) to achieve in difficult times.

How this element applied to the race to the South Pole. Roald Amundsen and his team of five men skied and sledged for 5-6 hours and went an average of 15 nautical miles a day.

Yet Amundsen did not measure his daily progress in hours, or even individual miles; instead, he used degrees. Fifteen nautical miles represents one-quarter of a degree of latitude, and Amundsen realized that knocking off one degree of latitude every four days and being able to imagine themselves inching their way across the map would be highly motivating for the team. One-quarter of a degree of latitude every single day: this was Amundsen’s clear performance marker.

Fifteen miles a day wasn’t a walk in the park, but it wasn’t exhausting either. Although it took grit and discipline, it was a pace that was doable in fair conditions as well as foul; whether it was calm or foggy or freezing, whether it was smooth sailing over flat terrain, or a team member and his dogs fell into a crevasse and had to be pulled out…on the men went, getting in their fifteen miles a day.

Scott, on the other hand, did not have a consistent goal for how far he hoped to go each day — letting the daily weather conditions and his fluctuating feelings of motivation dictate the pace. On a day with ideal conditions, he might push the men to trudge for 9 hours at a time. When the weather turned ugly, he might decide to not leave his tent at all, even though Amundsen was out in similar conditions.

How this element applies to your own life: Your performance markers basically set out your pace en route to your goal: the minimum effort you’re committed to making every day/week to get to where you want to be. This pace has to be hard enough to stretch you when conditions in your life are ideal, but still doable — as long as you exercise grit and discipline — during times when the poop hits the fan, or you’re simply not in the mood.

So for example, if your goal is to start exercising regularly, and you don’t exercise at all right now, creating a goal to work out for 90 minutes 6X a week is probably going to be impossible to stick with. Instead, pick a goal that’s going to be difficult for you, but still doable if you’re willing to work hard — say 45 minutes, 5X a week.

If you’re looking to write the next great American novel, consider setting a number of words you will write every day. Author JG Ballard (and many other writers) took this approach: “All through my career I’ve written 1,000 words a day — even if I’ve got a hangover. You’ve got to discipline yourself if you’re professional. There’s no other way.”

2. A good 20 Mile March has self-imposed constraints. This creates an upper bound for how far you’ll march when facing robust opportunity and exceptionally good conditions. These constraints should also produce discomfort in the face of pressures and fear that you should be going faster and doing more.

How this element applied to the race to the South Pole. Amundsen kept up his 15-mile-a-day pace for three-fourths of his journey to and from the Pole. When he was nearing 90 degrees south, he increased the pace a little to 20 miles a day, and did the same thing as he got close to his base camp on the return trip.

But other than these small deviations, it was 15 miles the whole way for him. It’s not that he couldn’t have easily pushed the team and their dogs to do more — they were healthy and eager — but he deliberately chose this pace so as to not exhaust his team and run the risk of injuries and sickness. Amundsen’s men passed most of their “down time†resting in their sleeping bags — up to 16 hours a day. But Amundsen saw this rest as a vital part of the overall plan.

For Scott, impatience was one of his weaknesses; he didn’t like sitting around and any kind of delay made him feel anxious. He also felt that if an effort didn’t tax you completely, it hadn’t been enough. Even after a long day of marching, he might decide to keep on pushing. Apsley Cherry-Garrard, who accompanied him part of the way to the Pole, recalled: “After nine or ten hours on the march, Scott would say, ‘Oh, well, I think we’ll go on a little bit more’…It might be an hour or more before we halted and made our camp: sometimes a blizzard had its silver lining.â€

Because Scott always liked to be going, it was harder for him to see how equally important rest was in the short-term in achieving his long-term goal. Scott pushed his men so hard on the way out to the Pole that the men did not have enough strength left for what turned out to be an even more arduous return journey.

How this element applies to your own life. A 20 Mile March creates two forms of discomfort. The first is the strain from hitting your performance markers as outlined in the first element. But the second form of discomfort can actually be more difficult to deal with — and that’s holding back, even when conditions are ideal for pushing harder. It’s easy to get excited about a goal and go full throttle after it, but this frequently leads to burn out and exhaustion before you ever reach what you’re after. It’s also easy to panic when you see what other people are doing instead of running your own race. Self-imposed constraints keep your short-term temptations in check in favor of continuing to steadily progress towards your goals.

For example, our newbie exerciser above might set 60 minutes a day as his max workout time, so that he doesn’t work out for two hours on days he’s feeling good and his schedule is free, and then feel so tired he doesn’t work out at all the next day.

This element is especially important to remember when you’re starting your own business or side hustle. You look around at what some other guy is doing, how his website looks, and what features he’s rolling out, and are suddenly beset with anxiety and self-doubt that others are outpacing you and doing a better job. Your panic turns into a decision to expand into things that aren’t really part of your vision, which weakens the enterprise and can lead to failure. Oftentimes, when you actually take a minute to reflect on the reality of the situation, you’re not really trying to do what the other guy is, and you’re unfairly comparing apples and oranges. Make corrections when needed, but try to stick with your own plan.

3. There’s no all-purpose 20 Mile March for all enterprises [individuals]. A good 20 Mile March is tailored to the enterprise [individual] and its [his] environment.

How this element applied to the race to the South Pole. One of the biggest factors leading to the failure and success of the respective expeditions centered on the forms of transportation each leader chose.

Scott, who patterned much of his trek after Ernest Shackleton’s 1907 Nimrod expedition, decided to use horses for a quarter of the trek and then man-hauling (the men put themselves in a harness connected to sledges and pulled them, step by step, through the ice and snow) for the rest, just as his predecessor had. But horses were ill-suited to Arctic conditions; they sweated through their hides, which then froze into sheets of ice and they had to be covered with blankets and covers to be kept warm. Moreover, their heavy weight and narrow feet ensured that they sunk deep into the snow and ice with every step. The man-hauling was disadvantageous simply because it was so physically taxing on the men to pull tons of gear 120 miles, up a 10,000 foot rise.

In addition to using the same modes of transportation, Scott used the same base camp area and followed the same route to the Pole as Shackleton had. Scott even checked his progress every evening against that of the Nimrod expedition.

Amundsen, on the other hand, took a different approach. After studying the ways of the Netsilik Eskimos, he decided that dogs were by far the best option for the Arctic environment: dogs ran quickly in the snow and ice and were low-maintenance haulers, they could be fed a variety of foods (including each other), and they kept warm by digging holes to bed inside.

Amundsen also made his base camp at the Bay of Whales, a spot no explorer had camped at previously, and pioneered a brand new route to the Pole. He didn’t know what terrain he’d face en route to his goal, but it was the straightest way there, and not only saved him 120 miles round-trip, but also ended up being an easier path than Scott’s.

How this element applies to your own life. Don’t simply copy the goals and plans of others. Your 20 Mile March needs to be tailored to your individual personality and the conditions of your environment. What worked for someone else (or even you at a different age), might not work for you now.

For example, the way you tackle a goal will be different when you’re a single, college student, than when you’re a married father. Here’s how I’ve seen this dynamic play out in my own life. Prayer, scripture study, and writing in a journal has been a priority for me for years, but finding time to do it since becoming a father has been tricky. Before Gus arrived in our family (and even for a few months afterwards – newborns sleep a lot), I often had an hour of distraction-free time in the morning to devote to those tasks. It was awesome! But I quickly learned that a toddler doesn’t care about your hour of “me-time.†So I’ve had to adjust. I now pray and write in my journal while Gus plays and Kate’s at the gym. Gus will sometimes come over and pull on the sleeve of my robe, demanding that I “get down on carpet!†(such a tyrannical tot!) to play with him. It’s not an ideal set-up, but it gets the job done (don’t worry — Gus and I have plenty of one-on-one play sessions at other times of the day).

4. A good 20 Mile March is designed and self-imposed by the enterprise [individual], not imposed from the outside or blindly copied by others.

How this element applied to the race to the South Pole. This element largely reiterates the previous one. While Scott blindly copied the plan used by Ernest Shackleton, Amundsen designed his own plan to arrive quickly and safely at the South Pole.

How this element applies to your own life. In order for your 20 Mile March to be truly effective, you need to be the architect of it. Studies show that goals that are imposed by somebody else are decidedly less effective than goals that originate from within the person. Creating our own 20 Mile March 1) gives us a sense of autonomy, which is highly motivating, and 2) allows us to craft it to our specific needs, which ups the chances we’ll actually succeed.

Don’t should on yourself by creating a 20 Mile March you think will please your parents, girlfriend, or friends. By all means, listen to their advice when they give it, but take what they say simply as that — advice. You decide whether to follow it or not. If it fits in with your individualized 20 Mile March, use it. If not, ignore it.

Also, following this element and the one above doesn’t mean you should never look at the 20 Mile Marches of other successful people. On the contrary, I highly recommend studying the lives of people you admire to discover what they did to achieve success. The key is to not simply copy the 20 Mile Marches of these folks wholesale, but rather to use them as inspiration and then to modify them to make the March your own.

5. A good 20 Mile March has a Goldilocks time frame, not too short and not too long but just right. Make the timeline of the march too short, and you’ll be more exposed to uncontrollable variability; make the timeline too long, and it loses power.

With this element and the next, because they don’t have a strongly resonant parallel to the race to the South Pole, I’ll keep it short and simply talk about how they apply to your own life.

It’s necessary to create a concrete timeframe in which to complete your goals – one that’s long enough to accommodate any unforeseen setbacks, but short enough so you don’t lose motivation and/or experience burn out. For example, if you have a goal to lose 60 pounds, a two-month timeframe to achieve that goal is too short in order to achieve lasting success. Two years is too abstract and long. Nine to twelve months is likely the Goldilocks Zone — long enough to allow you to overcome any setbacks, but short enough that the tangible deadline will keep you pushing yourself.

6. A good 20 Mile March lies largely within your control to achieve.

Don’t set goals where you’re not entirely in control of the outcome. So instead of setting a goal of getting into Harvard, or getting ten new clients – goals that depend somewhat on the behavior/decisions of others — set a goal to get straight A’s your senior year, or to call 100 new business prospects. Those are the kind of things you have complete control over.

7. A good 20 Mile March must be achieved with great consistency. Good intentions do not count.

How this element applied to the race to the South Pole. As discussed above, the key to Amundsen’s success was consistency. Even if there were gale-force winds, Amundsen traveled his daily 15-20 miles. “Travelled completely blind,†he wrote in his journal, “nonetheless we have done our [daily] 20 miles.” With slow, methodical, and dogged consistency Amundsen achieved his goal.

Scott on the other hand was inconsistent. Some days, when he was feeling strong, and conditions were good, he traveled 45 miles; other days he stayed huddled in his tent, unwilling to brave the harsh elements outside.

How this element applies to your own life. Just as in the race to the South Pole, the victor in life’s race is usually the doggedly consistent tortoise and not the sprint-and-snooze hare.

Barring life-threatening sickness or a family tragedy, put in your 20 Mile March each day. You’ll have days when you won’t feel like doing it. Maybe it’s too cold for your daily 3-mile run or maybe you’re too tired to write your daily 1,000 words for your book. Doesn’t matter. Put on your knapsack and get marching.

Conclusion

I promise you that as you apply the 20 Mile March concept in your own life, you’ll find greater success in achieving your goals. You’ll gain confidence in your ability to succeed even when adversity strikes because you’ll be putting in your 20 Miles even on days when it’s hard and you’d rather not. While you can’t control everything that happens in your life, you can control whether you put in your 20 Mile March for the day. As you see yourself steadily, consistently marching towards your goal, your motivation and drive will begin to increase, and will keep you going until you see your goal through.

What’s your 20 Mile March?