Welcome back to our series on the nature and power of ritual.

So far, we have talked about ritual’s ability to carve out pockets of the sacred in an otherwise profane world, as well as the way it can create group identity and solidify bonds between people by building shared worlds of possibilities between them.

In this final installment, we will explore ritual’s capacity to help a man make significant transformations and transitions, gain knowledge, and make real and meaningful progress through life.

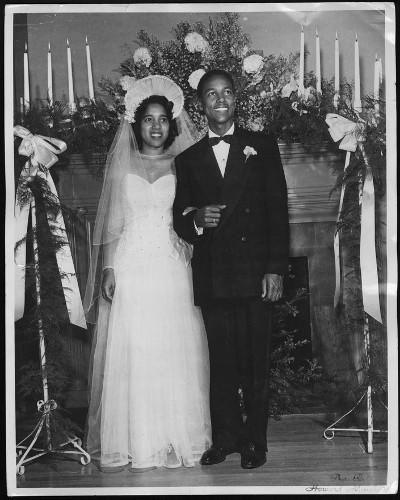

One of the primary functions of ritual is to redefine personal and social identity and move individuals from one status to another: boy to man, single to married, childless to parent, life to death, and so on.

Left to follow their natural course, transitions often become murky, awkward, and protracted. Many life transitions come with certain privileges and responsibilities, but without a ritual that clearly bestows a new status, you feel unsure of when to assume the new role. When you simply slide from one stage of your life into another, you can end up feeling between worlds – not quite one thing but not quite another. This fuzzy state creates a kind of limbo often marked by a lack of motivation and direction; since you don’t know where you are on the map, you don’t know which way to start heading.

For example, young men who do not undergo a rite of passage into manhood often struggle with still feeling like a boy trapped in a man’s body. They want to feel like a man, but don’t, and figure they’ll start acting like one when they start feeling like one. But this feeling never arrives, and the sense of being in limbo continues.

Just thinking your way to a new status isn’t very effective: “Okay, now I’m a man.†The thought just pings around inside your head and feels inherently unreal. Rituals provide an outward manifestation of an inner change, and in so doing help make life’s transitions and transformations more tangible and psychologically resonant. They do so in a variety of ways:

Rituals offer the chance at experiencing multiple “births.†Rituals tap into the timeless archetype of death and rebirth. This archetype — so present in nature, from the seasons to the human lifespan – can be found in cultures and religions all over the world, and is arguably deeply embedded in the human psyche. There seems to be a universal human feeling that one’s natural birth is not enough; there is a desire to regularly wipe the slate clean and begin things anew. “Life itself,†wrote ethnographer Arnold van Gennep, “means to separate and to reunite, to change form and condition, to die and to be reborn.â€

Ritual offers numerous chances to fulfill this deep need for fresh starts, and for feeling as though one is advancing and progressing through different stages of life. This applies to events like New Year’s celebrations and Christian baptism and confession, to various positions and merits like the Boy Scout ranks and the different degrees of Freemasonry.

Rituals make status transitions clearer and more powerful. Rituals help move you from one status to another by creating a multi-phase process that heightens and intensifies the transition. Rites of passage (and many other types of rituals as well) often follow the three-stage sequence laid out by Gennep: separation, transition, and incorporation.

First, you leave behind your old identity; then you exist for a time in an in-between stage; and then finally you are integrated into your new status. Joining the military is a perfect example of this process. When you enter boot camp, you’re stripped of your old clothes, your head is shaved, and you learn a new set of behaviors; for several weeks you exist in an in-between state where you’re not a civilian anymore but not yet a full-fledged soldier either; finally, you graduate as a ranking member of the troops.

By clearly delineating the transition from one status to another, this three-stage sequence is highly effective in shaping your mindset and getting you to leave behind your old identity and embrace and feel confident in your new one.

Rituals enhance the dramatic and narrative structures of our lives. Researchers have found that the human mind has a natural affinity for stories, and this predilection strongly extends into how we view and make sense of our own lives. We all seek to fit our experiences and memories into a personal narrative that explains who we are, when and how we’ve regressed and grown, and why our lives have turned out the way they have. We construct these narratives just like any other stories; we divide our lives into different “chapters†and emphasize important high points, low points, and turning points.

Psychologists have found that just like all good stories, the coherence of our personal narrative matters, and the more coherence our life story has, the greater our sense of well-being. But unfortunately, real life tends to happen slowly, moving in non-dramatic fits and starts that don’t fit together tightly nor have the kind of clear cause and effect that makes for a good tale. Turning points are often only recognized as such in retrospect. When bigger things do happen in our lives, they don’t feel as significant as we thought they would; ironically, real life often seems less real than what’s in our books and imaginations.

Rituals help make life’s transitions feel as substantive and interesting as you think they should. They can take a psychological, biological, or spiritual change that happens very gradually and non-dramatically — and thus wouldn’t make for a great movie or book scene — and turn it into a salient and tangible event. For example, while spiritual conversion is often a gradual and drawn-out process, one’s baptism day lends the story of your faith a clear and unforgettable turning point, adding vivid pages and a clear chapter to the book of your life.

By tapping into the archetype of death and rebirth and helping mark off different stages in our lives, rituals essentially take us through an encapsulated “hero’s journey.†And this micro hero’s journey in turn adds to our macro journey; in other words, rituals lend narrative structure to our lives by creating symbolic passages that weave strong, colorful threads into the fabric of our entire life’s odyssey.

Rituals create landmarks in our personal histories. The creation of these salient and indelible turning points not only lends a narrative structure to your experiences, but also creates permanent landmarks in your memory – signposts to which you can orient yourself throughout your life.

Something we have touched on repeatedly in this series is the way in which ritual can serve as an antidote to the flatness of our modern world and culture. Ritual not only adds texture to our culture as a whole, but to the landscapes of our individual pasts as well. When we feel lost in life and go gazing through the mists of time for clues on how to proceed, rituals are like prominent mountain peaks that we can always see, and that help us remember where we are and where we need to go. If our lives our like storybooks, rituals are like braille bumps; instead of our fingers blindly brushing over smooth pages when we go searching for direction, these bits of texture help us “read†and remember.

For example, if your marriage is feeling shaky, you may look back on your courtship as you think through what to do, but your love and commitment grew gradually and the memories are a little fuzzy and run together. Your wedding day, on the other hand, will stand out vividly, and you can look to that peak, remember how you felt standing at the altar and the vows you made, and re-orient yourself on your journey.

Rituals keep us from getting too far off track from our goals and purpose. Many rituals are designed to be engaged in regularly and act as reminders of one’s “landmark†experiences. Such “echo†rituals can keep us from even getting lost in the fog of life in the first place.

As we’ve talked about before, while we often know who we are and want to be, it’s easy to forget and lose hold of that vision as we go about our busy lives. Our purpose and values are like a rope that runs through our life and that we must keep ahold of day in and day out. Rituals of remembrance help us keep our grip on that rope through life’s dark tunnels.

For example, when members of the Church of Jesus of Christ of Latter-Day Saints take the sacrament (similar to the Christian Eucharist) each Sunday, they reflect on their baptism day, and spiritually renew the covenants they made with God during that “landmark†rite.

Tattoos are an even more literal example of a rite that creates a landmark with a very tangible echo; the act of getting the tattoo itself establishes the landmark, while taking time to look at it each morning continually reminds you of its meaning.

Rituals activate the act-to-become principle. The act-to-become principle basically says that instead of waiting for the right feelings to become something or someone, you act first as someone of that status would, and the feelings will follow. So for example, instead of waiting to act like a man until you feel like one, you act like a man first, and soon find that you feel like a man by doing so. Dr. Tom F. Driver argues that the act-to-become principle is so effective because “human lives are shaped not only, not even principally, by the ideas we have in our minds, but even more by the actions we perform in our bodies…we constitute ourselves through our actions.â€

In our first post in this series, we discussed the fact that all rituals are performance – actions in which there is an intended audience, even if that audience is just yourself. When you see yourself doing something, even if you don’t feel like the kind of guy who would do such a thing, you think, “Look at me doing X. I must be the kind of guy who does X.†Your mind closes the gap between your feelings and your actions; by acting, you become. Driver puts it this way, “There is a certain sense, an immensely important one, in which who we are waits upon who we say we are. When we perform ourselves, we do not simply express what we already are. We perform our becoming, and become our performing.â€

Rituals encourage embodiment. One of the maladies of our age is a feeling of disconnect from our physical selves. We spend much of our time interacting as disembodied personalities online, and don’t navigate the tangible world or connect with other people in the flesh as much as we used to. This can lead to feeling restless and untethered.

Ritual provides an ample antidote to this malady, for as Driver notes, “no good ritual is disembodied.†In fact, physicality is one of the linchpins of ritual’s effectiveness in advancing our personal progress and transformations. This power of embodiment provides the boost on several different fronts.

First, ritual offers the chance to get back in touch with our physical bodies and the tangible world. For example, primitive people had many hunting-related rituals – pre-hunt rituals to increase chances of bagging game, rituals for how to kill the animals, rituals for how to cut them up and handle the corpse, and rituals for how to eat the meat. Such rituals connected them to the rhythms of life and death. Today, we wolf down our food without even tasting it. We’re disconnected from the process of how we obtain and consume our sustenance, and this can have detrimental effects on our health. Rituals – such as saying grace before a meal or making coffee with a French press – can help us slow down and connect with what we are doing in the moment – settling our minds and reorienting our bodies in time and space.

The physicality of ritual can also work to bring us into a state of “flow.†Once you master the repetitive movements of a ritual, your body can perform them without thinking and you lose a degree of self-consciousness, opening your mind to insights from another level of existence. It is not a coincidence that many monks and ascetics ritualize nearly every aspect of their lives; by putting basic functions on autopilot, their minds are free to ascend to a spiritual plane.

Third, putting your body in a certain physical position can change the way you feel and alter your mindset, enhancing the effectiveness of the intended act. For example, if you wish to lose yourself in fervent prayer, kneeling or lying prostrate will immediately make you feel more reverent and humble than slouching in a chair.

Finally, the combination of thought + action can help us gain an understanding of truths in a profound way. As Driver argues, “we learn by doing; this includes the doing of ritual.†In the same ways that practicing, say, drawing a gun, can become part of your instinctive muscle memory, repeatedly performing a physical movement can help move the truths it symbolizes from your mind to the very sinews of your character. This “ritual knowledge,†anthropologist Theodore Jennings argues, “is gained by and through the body…not by detached observation or contemplation but through action. It is in and through the action (gesture, step, etc.) that ritual knowledge is gained, not in advance of it, nor after it.”

When you learn to use a tool (like swinging an axe), you bring your own knowledge of the technique to the tool, but the tool also “teaches†you as you practice – giving feedback to your hands, arms, and mind on how it is to be properly used. Gaining ritual knowledge, Jennings argues, works in the same way – when you handle symbolic physical objects during a ritual, they send messages back to you about their deeper meaning. This is why, Jennings argues, “ritual may serve as a mode of inquiry and discovery.â€

Looked at more simply, ritual makes gaining knowledge, especially of the esoteric variety, more effective than, say, reading a book or attending a lecture. Its physicality engages all the senses and activates the imagination. For example, learning about the ancient Israelites’ exodus from Egypt in Hebrew school is one thing, while sitting down to Seder and eating matzo and bitter herbs another.

Rituals invoke special powers. Rituals can summon and channel special forces that intensify and electrify an act, thus enhancing its intended effect. Driver explains this phenomena well:

“A ritual is an efficacious performance that invokes the presence and action of powers which, without the ritual, would not be present or active at that time and place, or would be so in a different way. The most obvious examples of such powers, no doubt, are divinities, demons, ancestors, and other spirits that may be called ‘supernatural’; but they may also be certain powers of nature, of society, of the state, or of the psyche.â€

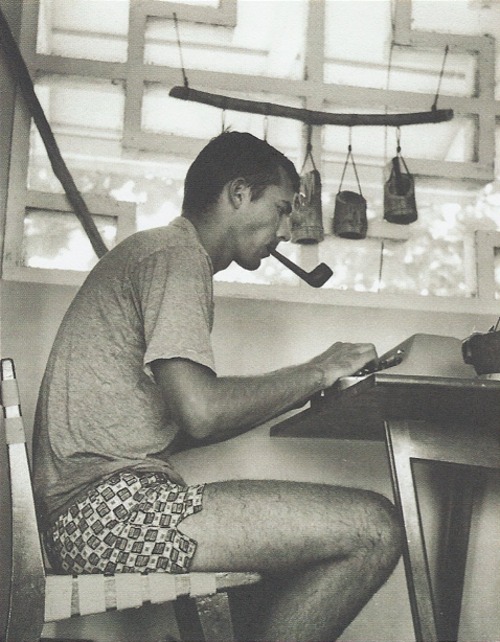

A perfect example of this are the various rituals many writers perform before they get down to work in hopes of priming their mind for inspiration. Some brew a fresh pot of strong coffee, go for a walk, or clear their desk of everything but their laptop. In The War of Art, author Steven Pressfield describes the pre-writing ritual he uses to prepare his mind to overcome “The Resistanceâ€:

“I get up, take a shower, have breakfast. I read the paper, brush my teeth. If I have phone calls to make, I make them. I’ve got my coffee now. I put on my lucky work boots and stitch up the lucky laces that my niece Meredith gave me. I head back to my office, crank up the computer. My lucky hooded sweatshirt is draped over the chair, with the lucky charm I got from a gypsy in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer for only eight bucks in francs, and my lucky LARGO name tag that came from a dream I once had. I put it on. On my thesaurus is my lucky cannon that my friend Bob Versandi gave me from Morro Castle, Cuba. I point it toward my chair, so it can fire inspiration into me. I say my prayer, which is the Invocation of the Muse from Homer’s Odyssey, translation by T.E. Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia, that my deal mate Paul Rink gave me and which sits near my shelf with the cuff links that belonged to my father and my lucky acorn from the battlefield at Thermopylae. It’s about ten-thirty now. I sit down and plunge in.â€

Rituals create structured pathways that facilitate the creation of personal identity and expression. While rituals constrain our options for behavior, and require subordinating some aspects of one’s individuality to the group, at the same time they paradoxically free up expression and make it easier to discover a greater sense of self.

Rituals set up what Driver calls an “economy of behavior†– routines that prescribe what to do in some aspects of our lives. Birthday party: balloons, cake, candles. Christmas: tree, lights, gifts. Choosing behaviors without these guideposts is like hacking your way through a dense, gnarly forest; exhausting work. Rituals provide a few pre-blazed trails; rather than using up all our energy on constantly re-inventing the wheel, we can use it for exploring further and deeper into the forest.

Stripping rituals from life was supposed to be liberating, but in a time when we are awash in personal freedom, an awful lot of people seem awfully dull and unexceptional. Worn out from having to choose their behavior in every situation with little guidance, and from creating every aspect of their own meaning and identity, people give up and seem passive and defeated, content to let the currents of consumerism carry them along. Carlin Barton, author of Roman Honor writes of a similar psychological fatigue that occurred as ritual disappeared from ancient Roman culture:

“Because for the cosmopolite, limits, like definitions, had to be chosen, morality and adhesion to particular traditions and limits required a prodigious act of will. Preserving a sense of being, of identity, thus became a continuous–and ultimately exhausting–assault on the will…For the Romans of the Late Republic and early Empire, too much relied on the will. As in a play by Seneca, there were not enough areas of life where one could submit; there was no psychic rest, no catharsis. It is much easier, as Mary Douglas points out, to maintain a sense of one’s own existence, of the expressiveness of one’s words and actions, in a world with stubborn bonds and traditions than in a world without them, however burdensome those bonds.â€

Rituals develop our practical wisdom. One of the most important ways that ritual actually facilitates rather than curbs expression is in the way it helps develop our practical wisdom – what the Greeks called phronesis. John Bradshaw, author of Reclaiming Virtue, defines practical wisdom as “the ability to do the right thing, at the right time, for the right reason.†Practical wisdom involves knowing the best way to respond in every situation – reacting neither too much nor too little and always choosing the balanced path of virtuous moderation.

How does ritual help you find that proper path? The authors of Ritual and Its Consequences give the example of teaching a child to say “please†and “thank you.†As we discussed last time, rituals create a shared world of possibilities – shared “as ifs†— and the rituals of social etiquette create a shared world of politeness. When you first teach a child to say please and thank you, you have to constantly remind them to do it, and it eventually becomes ingrained simply through the process of rote repetition. If you succeed in making the expressions of these pleasantries nearly automatic for them, they will for the rest of their lives make a small contribution towards creating that shared world of politeness whenever they interact with others. But the effect of the ritual often extends farther – helping them see all of life through a gracious and grateful mindset. Because they have for so long inhabited a subjunctive world of politeness, that world’s structure serves as a guide for how to act in situations where a ritual structures does not exist; practicing the please/thank you ritual develops their “ability to express gratitude effectively when simply saying ‘thank you’ would be inappropriate or insufficient.â€

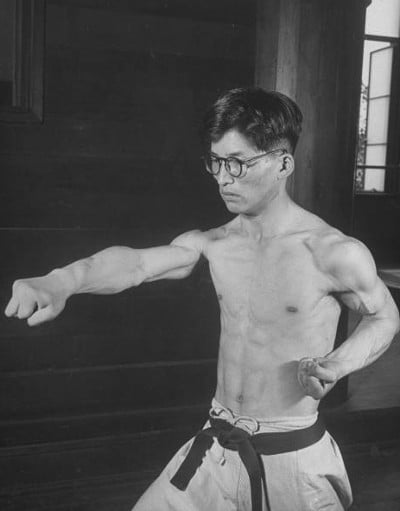

One can compare it to the way judges use the precedents of past cases to deliberate and come up with their own verdict. It is also helpful to reflect upon the forms or katas used in various martial arts. These choreographed patterns of movements are practiced over and over again, until the kicks, punches, and blocks are deeply ingrained in the practitioner’s muscle memory. It is not as if the marital artist will use the kata’s exact sequence in a real world fight, rather, as Wikipedia puts it: “By practicing in a repetitive manner the learner develops the ability to execute those techniques and movements in a natural, reflex-like manner. Systematic practice does not mean permanently rigid. The goal is to internalize the movements and techniques of a kata so they can be executed and adapted under different circumstances, without thought or hesitation.â€

The cultivation of practical wisdom is so tied up with the practice of ritual actions, that attaining the status of sage or prophet in many ancient cultures first required their mastery.

Ritual expresses, releases, and produces emotions. We often feel the need to do something physical in reaction to an event, and rituals can provide a catharsis that releases or at least alleviates anxiety, stress, doubt, anger, sorrow, and fear (not to mention positive emotions like joy as well). Inactivity can intensify negative emotions and deepen gloomy thoughts, and ritual provides a set pathway for behavior that can be chosen without much effort, so that you do not become paralyzed and overwhelmed in times of grief or stress. Barton offers a great example of this from ancient Rome. At the Battle of Caudine Forks, the Samnites barricaded the Roman soldiers in a narrow mountain pass. When they realized they were trapped, the soldiers:

“came abruptly to a halt, a stupor and a sort of torpor having seized their limbs. For a long time the soldiers stood in silence, immobilized, observing one another, each imagining the other to be more in command of his senses. Spontaneously, without having been given orders, they launched into the Roman soldier’s daily and arduous rite of building a stockade. The enemy mocked them and they mocked themselves, knowing full well the inanity of building a fortress within a cage. Still, the automatic and formalized behavior provided a relief from stupor. It allowed them to move and to show energy. The Romans, like Sartre’s Roquentin, needed to suffer in rhythm.â€

In the modern day, simple rituals like shining your shoes before a job interview can alleviate some of the nerves you are feeling and center you. Taking a morning run or slowly shaving with a straight razor can have the same effect, and can put you in the right mindset to tackle your day without stress and anxiety.

Rituals not only express one’s mental state, but can help positively create it as well. A war dance can stir up feelings of aggression, courage, and confidence while suppressing fear in preparation for meeting one’s enemy. Sports teams sometimes have pre-game rituals designed to produce the same effect. For example, New Zealand’s national rugby team famously performs the Haka in front of the opposing team before all their matches. The war dance not only psyches them up, but of also serves the purpose of intimidating their opponents.

Conclusion

If you have participated in rituals, but have not experienced the transformative benefits outlined above, or any of the supposed benefits of ritual touted in the previous articles for that matter, or, if you simply wonder why society has moved away from ritual if it’s really so great, tomorrow we will conclude the series with a short discussion on the nature of ritual resistance.

Listen to our podcast with William Ayot on a man’s need for ritual:

Read the Entire Series:

The Rites of Manhood: Man’s Need for Ritual

The Power of Ritual: The Creation of Sacred Time and Space in a Profane World

The Power of Ritual: Building Shared Worlds and Bonds That Transcend the Everyday

The Power of Ritual: The Rocket Booster of Personal Change, Transformation, and Progress

The Nature and Power of Ritual Series Conclusion: On Ritual Resistance

____________

Sources:

Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions by Catherine Bell

Liberating Rites: Understanding the Transformative Power of Ritual by Tom F. Driver

Ritual and Its Consequences: An Essay on the Limits of Sincerity by Adam B. Seligman, Robert P. Weller, and Michael J. Puet