In the play The Crucible, the character John Proctor, who is innocent of witchcraft, has decided to confess to conspiring with the Devil anyway in order to avoid being executed. He bitterly scratches his signature onto a written confession . . . and just as soon has second thoughts. He begs the colony’s deputy governor, Thomas Danforth, to accept just his oral confession rather than publicly posting this signed one:

PROCTOR: You are the high court, your word is good enough! Tell them I confessed myself; say Proctor broke his knees and wept like a woman; say what you will, but my name cannot—

DANFORTH, with suspicion: It is the same, is it not? If I report it or you sign to it?

PROCTOR, he knows it is insane: No, it is not the same! What others say and what I sign to is not the same!

DANFORTH: Why? Do you mean to deny this confession when you are free?

PROCTOR: I mean to deny nothing!

DANFORTH: Then explain to me, Mr. Proctor, why you will not let—

PROCTOR, with a cry of his whole soul: Because it is my name! Because I cannot have another in my life! Because I lie and sign myself to lies! Because I am not worth the dust on the feet of them that hang! How may I live without my name? I have given you my soul; leave me my name!

This little monologue is amazingly done by Daniel Day-Lewis in amazingly over-the-top Daniel Day Lewis form:

As Danforth refuses to accept anything other than a written confession, Proctor takes the one he signed and tears it up. His signature is such a symbol of himself, and his honor, that he’s willing to die rather than affix it to a lie.

A man’s signature has meant different things, and a great deal both personally and publicly, over the course of the last few centuries.

Still today, while we may not quite have Proctor’s passion for his signature, we frequently remain rather attached to ours.

If you’ve ever wondered exactly why, today we’ll unpack the significance of signatures, and contemplate the disappearance of such in the modern day.

A History of the Meaning of Signatures

The first use of signatures was as a means of authenticating documents, a practice which grew naturally from the ethos of traditional honor cultures, where one’s public reputation, one’s name, mattered supremely.

In the form of stamps, signatures date all the way back to the ancient Sumerians, while the practice of certifying official records with a written signature emerged among the Romans in the fifth century. The first government to codify the practice into law were the English, who in 1677 passed “An Act for Prevention of Frauds and Perjuries” which required that certain transactions be accompanied by “some note or memorandum in writing” that was signed by the participating parties. The act influenced commercial law throughout the West and set the standard for how documents were to be validated.

A meaning to signatures that transcended their more political/economic function has a more recent origin and really begins to take shape during the 18th century alongside the spread of literacy. The history of this social/personal significance of signatures (in the cursive form we know them today) not surprisingly tracks the same history for handwriting itself; the former represents a kind of distilled pinnacle of all the values that became associated with the latter.

The Signature as Self-Presentation

The first printing press in the British colonies was set up in 1639, and by the 1700s, printed publications began to overtake handwritten ones. But the rise of machine-created texts didn’t diminish the importance of the handwritten variety; on the contrary, the contrast lent the latter greater significance as a more human and personal means of communication. As Tamara P. Thornton points out in Handwriting in America, this is not to say that handwriting at this time served as a vehicle of self-expression, but rather of self-presentation; identity in the 18th century was not about individuality, but one’s sex, occupation, and class — one’s role and place in the social order. In the same way that dress and deportment delineated one’s position in society, so did one’s style of handwriting.

Initially, handwriting, and thus the ability to sign one’s name, was largely limited to literate, high class gentlemen, making it a mark of rank, breeding, and wealth. The illiterate could not write, and could only sign their names with an “X.”

Literacy, as well as handwriting, expanded through the 18th century and into the 19th, as a middle class of professionals (doctors, lawyers) and merchants began to emerge. Handwriting was particularly associated with commerce, as merchants had to do extensive record keeping, transaction making, and agreement formulating.

The social classes distinguished themselves by what style of “hand” they chose to write in. Men of business wrote with a bold, straightforward, crisp and accurate script, evidencing the command and efficiency appropriate to their profession, and the impression they wished to make on others.

Aristocratic gentleman, desirous to differentiate themselves from the common, mercantile classes — from those who had to work for a living — adopted a style of script befitting their leisured lifestyle. In writing only for personal pleasure, they could afford to be a little more decorative in their hand, a little more careless and illegible. As a book on penmanship from 1741 put it, the handwriting “admire[d] in fine Gentlemen” showed “an Easiness of Gesture, and disengag’d Air.”

As the definition of a gentleman changed in the Victorian era, so did the connotations associated with handwriting. “Gentility” shifted from being an exclusive function of lineage, to being a meritocratic quality of character. One’s honor became a matter of possessing inner traits like frugality, industry, discipline, and integrity, and it was thought that proper penmanship not only served as outward evidence of these inward virtues, but helped develop them as well.

Around the mid-19th century, the Spencerian style of script emerged as a standard model for penmanship, and its teachers and adherents made promises concerning its adoption that transcended the merely functional. This form of cursive necessitated exact physical positioning — the posture erect, the arm bent just so, even the feet pointed properly. The physical discipline required to write well, along with the mental discipline required to keep after the drills and practice necessary to perfect what was called a “noble and refining art,” was thought to build a man’s self-mastery, strengthening the will that made the development of all traits of good character possible. At the same time, his perfect penmanship furnished proof of his possession of such traits. In the negative sense, as a Boston school principal put it, “to write illegibly or badly is almost to forfeit one’s respectability,” while a penmanship copybook offered students a more positive maxim to repeatedly inscribe: “A neat handwriting is a letter of recommendation.” Just like his dress and manners, a man’s handwriting, and signature, were thought to be a calling card to his reputation (and were in fact used on his literal calling cards).

While handwriting was popularly seen during this period as outward evidence of inner values, it was still largely a matter of self-presentation, a manifestation of one’s public reputation and adherence to society’s honor code, rather than one of personal self-expression. But there was a group emerging at the same time which did see handwriting in just this way.

The Signature as Self-Expression

As society became more mechanized and urbanized, there were those who sought to counter these trends by elevating the power and value of the human, individual self. And among these Romantics, there were those who started to view handwriting as a notable expression of this unique self — a reflection of a person’s singular personality and mind. The way an individual’s handwriting deviated from standard scripts was thought to evidence unconscious manifestations of his energy, imagination, passion, creativity, and that most prized trait — originality.

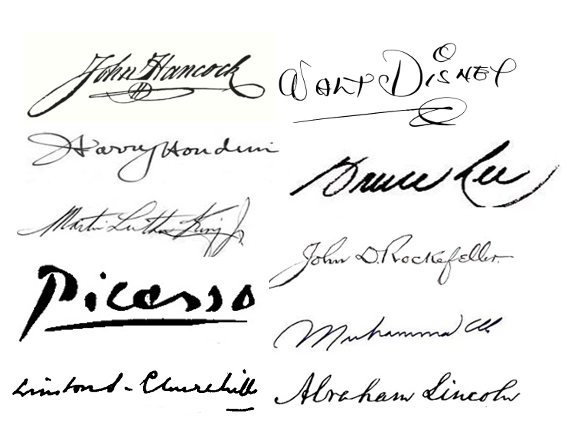

At the same time, the “hobby” of autograph collecting emerged, along with the belief that one could make contact with the above qualities by obtaining the signature of a genius who embodied them. If handwriting was an emanation from the unconscious of a person’s mind, then his signature — the very marker of his identity — was the most concentrated, tangible token of it: a magical, mystical talisman. As one autograph collector put it: “The characters of most men are commonly assumed to ooze out of their fingertips, else whence this pleasing hope, this fond desire, this longing after–an autograph?” Authors and artists often lent their signatures the same significance, making them loathe to share their autographs with hobby hunters; as one writer put it:

“An autograph is a manifestation–an exhibition of one’s private personality . . . It is a spiritual knock, given at the invitation of one who desires to piece out his inward life at our expense, refraining even thanks, because he thinks it costs us nothing . . . It is a lock of one’s mental and moral hair . . . It is a subtraction from our potency.”

By the latter third of the 19th century, the practice of autograph collecting had spread from focusing on the signatures of eminent creative types, to including those of one’s ordinary friends and family. It was popular to have a personal autograph book into which one’s intimates would inscribe their name (along with a clever saying, maxim, or line of poetry), not so much to capture their genius, but to hold onto a meaningful memento of their selves. The practice of classmates signing each other’s yearbooks developed for the same reason.

At the same time that signatures began to be seen as a medium of unique self-expression in popular culture, they also became increasingly admissible in court as proof of informed consent, intent, and authentication. An individual’s handwriting came to be viewed both commonly and legally as being as distinct as his voice, face, and even fingerprints; it was thought that no two were exactly alike.

The idea that handwriting conveyed a person’s psyche and temperament went truly mainstream at the turn of the 20th century. As the typewriter took over the production of more and more written texts, the significance of handwriting only deepened. Because public documents were almost uniformly typed, handwriting became ever more associated with the realm of the private, the human. Even on typed correspondence, one’s name continued to be signed in ink, a personal touch that certified the sender’s intent, and sincerity.

At the same time, while people were largely self-employed in the 19th century, in the 20th they increasingly became the employees of large corporations, and, feeling their identity subsumed in this bureaucracy, looked to handwriting to find evidence of their unique individuality.

In answer to this desire, “graphology,†which purported to be a “science” that could deduce a person’s personality by analyzing the tiny nuances in the lines and curves and slant of their script, came to great prominence. Through the 1950s, graphology remained enormously popular with the public — being demonstrated at Rotary luncheons and traveling shows and explained by experts in newspaper columns and radio programs.

Given that handwriting became such a strong symbol of who you were, in a time in which people worried about losing themselves in the anonymity of the masses, it became increasingly acceptable to allow one’s personal penmanship, and particularly one’s signature, to deviate from the standard scripts. The Spencerian model and the popular Palmer method which followed it had never called for complete uniformity, and handwriting experts had long felt that people would naturally and unavoidably end up tweaking these standards into their own style. But cultivating that unique flourish now became a bit more intentional.

Professionals like lawyers, doctors, and academics, who held themselves above the common, more conformist fray, followed in the footsteps of the gentlemen of old by often deliberately cultivating a little illegibility in their signatures. As one 20th century penmanship teacher noted, “No doubt there comes a time in the life of every student, when he feels there is a certain amount of prestige attached to the ability to create an indecipherable signature.”

As we can see in this brief history of signatures, one’s “John Hancock” has held some weighty associations through the centuries: a public sealing of one’s honor, a way of certifying legal and business transactions, a sign of status and education, a marker of discipline and character, a reflection of mind, an expression of personality, a human bulwark against the homogenizing effects of mechanization. Echoes of all these meanings remain with us today, so that it is no wonder we remain a little attached to our signatures. But could that attachment finally be slipping away?

The Signature as Disappearing Symbol

If the fortunes of signatures have ever been tied to that of cursive handwriting, then it is unsurprising that the importance of the former has sunk in tandem with the latter.

First came the rise of manuscript or block lettering in the 20th century as an alternative to cursive. Today some schools have stopped teaching cursive to students altogether.

But the real downfall of script, of course, came with the advent of the personal computer. No longer were public documents typed and private handwritten — even personal correspondence began to be produced with a keyboard rather than a pen.

A blow fell to signatures in particular in 2000, when the U.S. Congress passed the Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act, which made eSignatures as legally binding as the handwritten variety.

Today, you can “sign” something with the click of a mouse or the scribble of a stylus on a credit card machine — even a meaningless squiggle is accepted.

Because young people may have received little instruction in cursive in school, and then not often had to practice writing their signature while growing up, when it comes time to sign something like a check or passport or application, they sometimes struggle to do so, and may inscribe their name with block letters instead.

The significance we lend signatures has diminished alongside their prevalence. Trying to get a selfie with a celebrity has replaced trying to get their autograph. Students still often “sign†each other’s yearbooks, but rarely do so in cursive.

Still, an attachment to real signatures remains. We still hold press events to watch a president hand sign a new congressional bill. When someone sends us some kind of correspondence, we still look to see if the signature is real, and feel a little disappointed when it’s the work of an autopen. A handwritten signature still signifies a personal touch, extra time, attention, and sincerity. Something with a handwritten signature on it still feels like you’re holding a piece of the person, still makes for a memento you’re more likely to hold onto and preserve. We still say we’re “signing off” on an idea, even if it’s just in a metaphorical way, to voice our consent.

Some say the disappearance of the signature is no great loss; it’s only been around for a relatively short time in the grand scheme of things, and our modes of communication are always changing. Which is true enough. But one can’t help wondering if there might be something special in this particular mode of expression that isn’t entirely replaceable. Indeed, one wonders if John Proctor had only to click his mouse to submit his confession, whether he would have agonized as much over the decision . . .

Listen to our podcast on the power of penmanship:

_____________________________

Sources:

Handwriting in America: A Cultural History by Tamara Plakins Thorton

The History and Uncertain Future of Handwriting by Anne Trubek