So after being on hiatus for nearly a year, I’ve decided to bring back the Art of Manliness podcast. Thanks to all those who emailed and messaged me asking that I bring it back. Your desires have been granted!

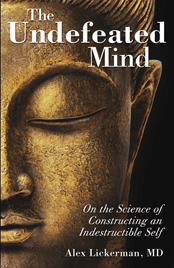

To kick off the resurrection of the AoM podcast, I talked to Dr. Alex Lickerman. Dr. Lickerman is a practicing physician and author of a recently published book entitled The Undefeated Mind: On the Science of Constructing an Indestructible Self. If you enjoyed our series on the power of resilience, you’re going enjoy my conversation with Dr. Lickerman and his book, Undefeated Mind.

Highlights from the episode include:

- How to not only survive adversity, but thrive in it

- What Buddhism and Stoicism can teach us about building resilience

- Why perception is key to building the undefeated mind

- How you underestimate your ability to face adversity

- How to turn poison into medicine

- And much more!

Listen to the Podcast!

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast so, yeah we have been on hiatus with the podcast for almost a year. I stopped doing it because we just got too busy with other projects and other things, but I have had a lot of people e-mail me, Tweet me, Facebook me asking, hey, when are you going to bring the podcast back, so we’re doing it now. And, I’m really excited about our guest that we have on today. His name is Dr. Alex Lickerman. He is a physician, a practicing physician, but he is also the author of a book that just came out last November, it’s called The Undefeated Mind: On the Science of Constructing an Indestructible Self it’s all about building your resilience, something we have talked about on the site before and he goes into depth, brings in a lot of scientific studies that talk about how you could become more resilient, how you can strengthen your I guess your mental fortitude to handle whatever challenges that come your way. Well, Alex, welcome to the show. We appreciate you taking time on of your busy schedule to talk to us.

Dr. Alex Lickerman: Thanks so much for having me.

Brett McKay: So, Undefeated Mind that’s what the title of your book is called. How would you describe a person with an undefeated mind and why is it so important that we try to develop this undefeated mind you talk about?

Dr. Alex Lickerman: So, I think about an undefeated mind is basically a mind that is resilient and by resilient I mean two things and they are sort of the two sides of one coin. The first side is that when bad things happen, when adversity strikes, when tragedy lands on you that you are able to not just survive it, but actually thrive in the face of it, so that may mean you go through it maintaining, you know, your poise and your confidence or maybe you go through it and you’re horribly discouraged and even depressed and anxious, but that at the end of it, you come out of it, sort of not just back to where you were, but even stronger in some way. The other side of that coin though is that when you are striving to achieve something you have a goal that you don’t know if you can do it, that when the obstacles arrives, that invariably arise whenever people try to achieve something great, when those arise that even if you become discouraged, it does not stop you, as you continue on no matter what, but you don’t give up when everything is telling you to give up and you feel like you need to give up, but that it’s hopeless, but you go on and then even if you don’t achieve your goal, the reason you don’t achieve isn’t because you quit, but just because it didn’t work out.

Brett McKay: So resilience and hardihood is how you describe some of the undefeated mind?

Dr. Alex Lickerman: Yeah. That’s basically it, personality hardiness, yes.

Brett McKay: So, what experience is in your life led you to discovering the principles and practices that you talked about in your book. I found that very fascinating, you talk about some of your experiences what were some of those principles and personal experiences that led to the book?

Dr. Alex Lickerman: Yeah so I – as I talk about in the book, I’m a Buddhist and I started practicing Buddhism, my first year of medical school and frankly up until that point, I hadn’t really encountered any obstacles or tragedy in my life out of the ordinary and then the woman who introduced me to Buddhism in my first year of medical school was a woman I then began dating, she was the first great love of my life and when we broke up I was just absolutely devastated. I was in retrospect now absolutely probably depressed, but since it was on my first year of medical school, I had not yet learn to diagnose that, so I didn’t know I was depressed and I was just completely shattered by it and the practice of Buddhism involves chanting, it’s a little bit foreign to many of those of us raised in the west, but it’s sort of a form of meditation and it was actually while doing that and chanting about the fact that I was just suffering far out of proportion to what I thought I should be just because I had broken up with my girlfriend and I had a great insight and intensity that the reason I was suffering really had nothing to do with the fact that she and I had broken up, but what I believed that meant, and what I believe that meant I was surprise to discover at that moment was that I could never be happy that without this woman to love me, my chance of happiness was gone. And I was stunned to discover this and from that insight, I realized that the key to being happy you know how can we be happy when so many terrible things happen to us. There is no way any of us gets a little life without having trauma and tragedy happened in our life, which just doesn’t happen. You live long enough things going to happen so, how can we be happy when those things happen and the answer is we have to become so strong that no matter what happens to us we feel we had some power, some ability to overcome whatever it is that’s happened even if it is not overcoming in a way we want to overcome it, but still in some way achieve some kind of victory, so that we can say we’re done with this, we got through it, we overcame it and we’re moving on and maintain our ability to be happy. It’s really – the bottom line is it comes down to happiness and strength.

Brett McKay: Yeah. What I found fascinating was your practice of Buddhism, and you practice a particular kind of Buddhism I never heard of what’s it’s called again?

Dr. Alex Lickerman: It’s called Nichiren Buddhism.

Brett McKay: Okay.

Dr. Alex Lickerman: And it’s – the practice is chanting a phrase, which is Nam-myoho-renge-kyo and the idea the Buddhist will tell you that the reason chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo has the power it does it because you’re tapping it in to a mystic life principle. I don’t actually believe that I have to say, but I have still found that chanting that phrase over and over again with – it’s not like meditation, we were trying to focus on the moment and clear your mind of thoughts, it’s actually in a sense it’s a war cry, you are making determinations when you are chanting that you are going to solve your problems because a lot of times problems occur to us or happen in our lives and we think we know how to solve them and we try those things and they don’t work and then we tried something else and it doesn’t work and when we exhaust those possibilities typically what we do is go back and start trying same thing we tried the first time even though it didn’t work the first time because we’re out of ideas. What I’ve learned through the practice of Buddhism is that there often are answers buried within me somewhere that either haven’t occurred to me or they have, but I haven’t truly opened my mind to the possibility of trying to employ some of those answers because they’re either too fearful, I’m too fearful or they seem to risk too much. What I have learned is that when I chant with a focus determination to overcome a particular problem answers will often come to me and it just sort of pop up just the ways thoughts do that are surprising that are not things I would have thought of on my own, but that end up often being the very things I need to do and sometimes things I don’t want to do, but if I could only master the courage to the man end up being the things that enable me to solve the problem.

Brett McKay: What I found fascinating was the insights you gained from Buddhism and the ancient philosophy, what I found fascinating throughout the book you show how cognitive science is actually confirming the insight to these, you know, ancient philosophers had thousands of years ago.

Dr. Alex Lickerman: That’s what actually sparked my interest in writing the book was that you know in studying Buddhism for all these years I have done and being a physician and taking care of patients, I’m very much evidence based. I need something prudent to really believe it and I have started looking into a lot of research and then ended up sort of supporting a lot of these 2500-year-old ideas and, you know, we finally applied modern scientific methods to asking these questions and that the answers end up being what the Buddhism has been taking about all long, so it’s kind of a neat synergy.

Brett McKay: Yeah so, going back to where you talked about your experience with breaking up with the first love of your life and you said that thing that really I guess the epiphany you had was your change of perception, right, you had this perception change and it seems like that was a main thread throughout your book, that’s a main principle, what I found interesting, I’m not very familiar with Buddhism, but one philosophy that I’m familiar with is stoicism of the ancient romans you know Seneca and Marcus Aurelius and that’s something they talk about too that are the pain that we experience in life often isn’t caused by a tragedy, it’s our perception of that tragedy and it’s kind of a hard, I guess a hard concept for us moderns to swallow this idea that our perception is what causes us pain.

Dr. Alex Lickerman: It is, but Buddhism and stoicism are very similar that way. The idea is that it really is that what happens to us, how we think about what happens to us that affects the way we feel about it and this is not too hard a concept that grasp, you pause for a few minutes and then examine just your own reactions to things in your life. When something bad happens or something difficult arises in your path when you are trying to reach a goal, if you feel that you can manage it, it may be uncomfortable or it may be depressing to imagine, but you’re not defeated by it if you feel confident to be able to solve that problem if you are thinking about in such a way that you can solve the problem. On the other hand, if something happens where you think I don’t know what to do, the next thought that most of us have automatically is there is nothing that we can do and therefore that’s when depression can set in and so it really is our thoughts about things that govern our emotional responses. It’s our emotional responses that matter, are we suffering over this or are we not, and there is this thing, this really is reflected in modern psychology and cognitive neuroscience, there is this notion of the self-explanatory style that we all bringing to our life, so when things happen we typically explain them to ourselves why did I fail that test or why did that girl turn me down for a date and we come up with our explanations that we don’t notice this, but we quickly settle on them as true without often any evidence whatsoever our first thought often is what we decide this is the reason, the girl turned me down because I am not good looking enough or because she is snobby or I failed that test because I’m just not a good test taker. What we don’t realize is that these ideas are just that, they are just ideas, you know, they may be right, but more often than not, they are wrong and yet we completely believe them without any question, the moment we think the most of the time and that governs not only how we think about what happen and therefore, how we feel about what happen, but also what we’re going to do, you know, so for a test taker, if someone fails a test, they say I’m just not a good test taker. I failed that test because I stink at taking test. They are far more likely to not study for a make-up test and fail it again, but instead if they tell themselves when they fail the test, you know, I failed that test because I just didn’t study hard enough. I got to study harder, but then they’re much more likely to study harder the next time and therefore more likely to pass the test so, it’s not even just how you feel about what happens to you that is determine by your perception, but what you do about it and what you’re able to do about it.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So, do you think as I read this book I started of thinking about, I have ancestors right that cross the plains in covered wagons and you know you read journals entries that they face so much adversity, children died and I just – despite that, they’re able to continue, they’re able to thrive and I look at my life and I think I couldn’t do that, I mean, I can’t believe what they are able to do. Do you think modern society in some ways has made us less resilient in some ways?

Dr. Alex Lickerman: No. No, I don’t. I think that your estimation what you’re able to handle is wrong. You can handle far more than you think you can. It’s interesting because they have done studies on people’s expectations for how they will be affected by trauma in the future and reliably people far overestimate how devastated they will be by imagine traumas and don’t actually predict how well they will be happy in the future either, so you look back at your ancestors who went through some of those trials you see yourself hike, I could never have done this, but in fact where you confronted with it, the answer might be very different and you don’t really know how strong you are, how resilient you are until you are facing the trial that forces you to be resilient, you know, in the sense, you know, strength only appears when you are forced to lift the heavy weight that’s when you know how strong you are, so I suspect that in general the population alive now modern people are actually as resilient as our ancestors we just haven’t had to face the same things, for which we all are very grateful, but if we were to I think we would surprise ourselves.

Brett McKay: So, I guess the takeaway there is whenever you do face a really life changing adversity or life changing challenge, I guess the takeaway is realize you’re going to be able to get through it and you’re stronger than you think you are.

Dr. Alex Lickerman: Absolutely right. Interestingly, when you look at studies that people who have actually gone through horrible things that most people don’t go through and you look and see over time how they do. Most of the time, most people not only get through those things, they come right back to their previous level of happiness whatever that was eventually, but what’s interesting is when you tell people that and you say, you know, there really are great studies that show it outflow that seems today you will eventually be happy again, knowing that even when people believe, it does not by itself made going through that thing easier, it’s not enough just to know it, but sometimes it is, sometimes people will have that thought and they think I will be happy again and when they believe it, that can sort of get them through this, but again that’s why I wrote the book to sort of hand people techniques they can do to sort of maintain their confidence and their resilience when they are going through those really difficult times.

Brett McKay: Definitely. So, another one of my favorite concepts in your book is this idea of turning poison into medicine and can you explain what you mean by this and maybe give an example of turning poison into medicine?

Dr. Alex Lickerman: Sure. So, it’s a Buddhist idea and the notion is that it seems to be inherent within the human mind and the human heart that when tragedy or trauma adversity strikes, we are so quick to judge the final value of those events as all bad that in fact we have within us the capability of transforming events that appeared to be all bad and wants into something that create a value for us. Now, this doesn’t mean that you can reverse necessarily the bad thing that’s happened to you know if your son dies of horrible thing, it doesn’t mean that you’re going to bring your son back to life by any means nor does that mean necessarily, you’re going to be as happy as you were or that you are going to ever stop hurting or missing your son, but what it means is that there is nothing that could happen to you, no matter how often you could imagine from which you cannot create value, some value and in fact you know at really most extreme circumstance you talk about, parents losing children studies have actually shown that parents actually do get surprising benefits from that, as almost kind of perverse that sounds that they become closer to their surviving children that they become more courageous in general. I’m not for a minute suggesting that those benefits make up for such a loss, but a lot of times in more mundane, more common loses and traumas that we may suffer; you actually can come out actually ahead. You just can’t predict the future so, you know, the example that I would give, which I think I read about in the book as well is my – when I was a second-year medical student right after my girlfriend’s, first love we talked about when I broke up, I became so depressed. I couldn’t concentrate, I couldn’t study and I failed part 1 of the National Board Exam and I thought my life was over, I thought you know if you don’t pass part 1, you can’t graduate medical school. I was already in debt and I thought I’m not going to become a doctor. I don’t know what to do because I didn’t have time to study for, you’re supposed to launch into the third year, which is where you do all your work with patients, a year that is renowned for swallowing days at a time, of a person’s time so, you know I thought this is the worst possible thing that could have happened to me, but so rather than giving up, I just decided okay so my choice is to drop out of medical school or I am going to find some way to study of this test take it again and pass it and I decided that’s what I was going to try to do and ultimately did it by completely eliminating any free time, any social time whatsoever for a year and got through it and scored actually above the mean, which I have never done at any test prior in medical school and then, so I thought okay I got to that. I graduated got a great residency and ended up as a teaching attending at the University of Chicago and then one day a student had come to see me who had failed for third year internal medicine clerkship rotation up on the wards again you could imagine just devastated and I found myself telling her the story of how I had almost completely walked out of medical school, but I persevered and was able to succeed and eventually passed the test and I told her you know I realized that being forced to go back and study there material made me a better doctor that I as a result of that I am learning the material again. I learned it and could sort manipulate it and think about medicine and science in a way that I was looking around and seeing my peers really weren’t doing and in many instances, it was leading me to make diagnosis, I really didn’t think I otherwise would have made, but then the real benefit, the real medicine of that constant experience was then suddenly, I had the story to tell her and in telling her I could see I really was watching her hearing my story and her face changing thinking, I know what she was thinking, she was thinking if he could do it, then I could do it and I think you know even we can’t find some benefit in horrible tragedy or trauma that’s happened to us, so we don’t you know actually created some real victory that we feel in some way we won, we could always use those experiences to encourage other people and in that way create a value that can be surprising to us and really actually enable us to one day say, I’m almost glad that happened because I have been to encourage some many people with that story and I have with that story.

Brett McKay: That’s fantastic. So, what do you think is one of the more counter intuitive principles or practices that you talk about in the book that if someone applied they would become more resilient, more hardy, but if you told them that hey you need to do this they would think, no that wouldn’t work and I’m not going to do that. Are there any counterintuitive principles or practices like that?

Dr. Alex Lickerman: So, one of the them that I consider counterintuitive at least it was to me when I sort of stumbled across it is the notion of accepting pain. People who likes to lift weights really hard, they get this already. They understand that pain is gained, but when you apply that sort of to your life, it becomes a little less obvious how that can be beneficial, but it basically works like this. So, it turns out that a lot of suffering that people experience in life is not as a result of bad things happening to them, but it’s as a result of them trying to run away from the bad feelings that bad things happening causes. So, people turn to drugs and alcohol because they’re anxious about things and end up destroying their lives when you know really just trying to avoid the feeling of anxiety or men will try to sabotage relationships with women to prevent the women from breaking up with them because they have such a fear of rejection and so they ruin particularly healthy and happy relationships because of their fear. They are trying to avoid something that feels bad. And so, you know, the idea is that there is legitimate pain for us to feel and that when we feel it, we should allow ourselves to feel it. It can be very powerful because we all have goals in life and it is often our own uncomfortable feelings that prevent us from achieving them. So for example, if a man wants to ask a woman out or maybe go to parties to meet women, but has horrible social anxiety just really has a hard time doing that. It’s actually the feeling of anxiety that they want to avoid and so they learn to avoid by avoiding the circumstances that trigger it, meeting, you know, asking women out and going to parties. On the other hand, they have this goal of wanting to meet somebody. So, what do they do? Well, there is this new therapy called acceptance and commitment therapy that basically talks about this notion of acceptance, which is that you say to yourself my goal is not to stop feeling anxiety, I’m going to allow myself to feel anxiety and I’m going to actually take the action that’s going to get me towards my goal even if it makes me feel anxious. I’m going to accept. I am going to anxious. Just that mental 180 where you stop reflexively trying to avoid those painful feelings and allow yourself to feel them is incredibly empowering and adds to resilience and interestingly and paradoxically, what studies have shown is that when people actually approach say anxiety that way, it actually reduces anxiety, which importantly is not the goal, it’s not the goal. The goal is to actually to become more comfortable feeling it and not allowing it to stop you from doing what you need to do to accomplish the goals that you have. And so, I have actually you know done this, introduced this principle to many patients of mine who have told me that it really does work when you suddenly transform yourself from someone who does everything they can to avoid whatever pain you’re feeling, you know, it can be even physical pain to someone who sort of bucks up and say yeah I can withstand this, it’s really awful, it’s really uncomfortable, but I’m just going to suck it up. Suddenly, you become really powerful and the things you were able to do will surprise you.

Brett McKay: Seems like yeah by taking away the uncertainty of pain and accept yeah, you no longer uncertain that there will be pain that anxiety clears up.

Dr. Alex Lickerman: Yes. I mean, you accept the fact and you’re actually in a sense almost embrace it, you know, the way a weightlifter embraces the pain of lifting weights because he understands it’s the pain that represents hard work and therefore growth. And so, the experience of feeling even physical pain when you understand that it does not mean harm that it’s okay to feel it, it’s much less emotionally aversive. It’s interesting they have actually studied when people experience pain that is caused intentionally by someone, it actually hurts more and when pain is caused by someone accidentally, the way we think about has a profound effect on our subjective experience of it.

Brett McKay: That’s really interesting. Well here is the last question. As I read this book, I kind of perceived that developing an undefeated mind is a lifelong process. It’s not something that is going to happen overnight. So, my question is how do you maintain the motivation to develop an undefeated mind or more resilient personality when you face setbacks in the process because I have had this challenge. I’m trying to work on becoming more hardy and more resilient and I’ll do good for a few weeks and then I’ll this something that happens where I just break down and I kind of have this breakdown in my resilience and yet. I begin this like cycle where I get discouraged about, my inability to be resilient and I get sort of this horrible cycle where I just sort of remunerate about things. So, yeah what’s your advice on someone who wants to develop a more resilient attitude, a more undefeated mind, how do they maintain that motivation to do that?

Dr. Alex Lickerman: So, if I use, you know, you just said as an example you would – think about it like a dieter, somebody who’s trying to lose weight. So, what dooms people who are trying to lose weight is not when they cheat on one day and they got, you know, they blown and it turns out that caloric intake on a daily basis does not correlate to long-term weight gain or weight loss, which means if one day out of the week, you eat terribly, but then immediately go back to eat to following your diet, it is just that one day didn’t happen. What dooms people who are dieting is when that one day happens, when they get into temptation and then they blow their diet then they say to themselves, I’ve blown it and they call themselves all types of names and then they say well, I may as well give up because I’ve blown it already, it’s too late. And then, it is the subsequent days that actually ruined them. So, if for example you know when you are trying to become a resilient person you are doing really well and then something happens you get knocked of the horse and then you say, I blew it again and I just can’t do this. First thing is you don’t judge yourself because, you know, being resilient doesn’t mean you won’t get knocked off your horse. You need to get back up on it. So, it’s really hard to practice the things that I talked about in the book to develop yourself into a more resilient person when you are not facing something that makes you need to be resilient and of course if you are not facing that at the moment, it’s okay you don’t need to sort of practice these things other than, sort of be prepared yourself when something does happen you can reflexively go to them, but I view like when things hit you as an opportunity for you to train yourself to be more resilient, sort of like you know when you lift weights, you’re not going to feel your strength, experience your strength, or actually increase your strength unless you’re actually lifting them. There’s got to be some obstacle for you to push against, so in fact it’s those very moments when you feel most discouraged since you have the greatest opportunity to actually become resilient, but even I, you know, I’m being in this place for 20 plus years and I wrote this book when bad things happened often my first reflexive response is oh no! and what am I going to do when I can’t survive this. And then, you start to have to, you have to reflexively get to the habit of examining your negative self-talk and recognize that this is just another voice in your head and say remind yourself I do have the tools to become resilient, I just have to grab hold of them and pick them up. Sometimes, it takes longer, you know, you don’t do it right away, sometimes it takes a week, sometimes longer, but at some point, you do have to say to yourself okay, I have to own the situation, I have to figure out what I can do and take care of myself and puff up or buck up my inner self, so that I can actually manage the situation, so once you suddenly start having those thoughts and then you remember, oh yeah there are these things I can do. I have learned to do that actually will lead me to success and help to buoy my life condition while I’m going through this. So, it is like anything else. It takes continual practice, which means sometimes you’ll be better at it, sometimes not as good, be very gentle with yourself. If you don’t meet your expectations today that’s fine, that’s okay as long as you try again tomorrow you are being resilient.

Brett McKay: Very good. Well, that’s actually really helpful for me. Well, Alex, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us. The book is The Undefeated Mind on the Science of Constructing an Indestructible Self and you can find that on Amazon. Alex, thanks again for being with us.

Dr. Alex Lickerman: Oh, thanks so much, I really enjoyed talking.

Brett McKay: Well that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast, for more manly tips and advice make sure to check out the Art of Manliness podcast at artofmanliness.com and until next time stay manly.