“Manhood is the social barrier that societies must erect against entropy, human enemies, the forces of nature, time, and all the human weaknesses that endanger group life.†-David D. Gilmore

There is much discussion these days about manhood and the future of men. Sometimes I will see people try to stop one of these conversations before they even begin by saying something like, “Talking about what it means to be a man is meaningless, because the whole idea of manhood is totally relative. It’s different in every culture and has changed throughout time.â€

There is some truth to that argument, in that the ideals of manhood have indeed varied over the centuries and around the world. But it is quite wrong in the assumption that these ideals have not shared some unvarying commonalities. Manhood has always meant something, and though it may come as a surprise to some, it has always meant pretty much the same thing to nearly every society in the world.

This is the finding of one of the few, if not the only book to have made a thorough cross-cultural study of the many ways masculinity is perceived and lived out around the world: Manhood in the Making by David D. Gilmore. I actually had thought I read this book around the time I started the blog and that I had not gotten much out of it. But I recently picked it up again and found to my surprise that not only had I only skimmed it previously, it turned out to be the most enlightening book on manhood I had ever read. If you’re interested in the nature of manliness and masculinity, I highly recommend giving it a read. It’s helped me think through the meaning of manhood on a new level, and I’m very excited about using it as fodder for a number of posts now and in the future.

Today I’d like to start with one of Gilmore’s primary findings: that the concern for being manly, far from being a peculiarly modern phenomena, an American obsession beget of a frontier past, or a cultural quirk that developed in a few pockets of the world, has instead been shared by nearly every culture in the world, both past and present. Societies as far-flung as Japan and Mexico, New Guinea and India, Kenya and Spain, had and continue to have a cultural conception of a “real man†— an ideal to which all males are expected to aspire.

Not only is the belief in a code of “true manliness†nearly universal, there are, as anthropologist Thomas Gregor puts it, “continuities of masculinity that transcend cultural differences.” While every society’s idea of what constitutes a “real man†has been molded by their unique histories, environments, and dominant religious beliefs, Gilmore found that almost all them share three common imperatives or moral injunctions — what I’ve taken to calling the 3 P’s of Manhood: a male who aspires to be a man must protect, procreate, and provide.

What is so striking is that this triad of male imperatives can be found in cultures that share little else in common. They are the “deep structures of masculinity†and are present in societies that are patriarchal as well as those that are relatively egalitarian, primitive as well as urban, bellicose as well as peaceable.

The 3 P’s are not universal, as there are a few cultures where no ideal of manhood exists at all. But these exceptions are so rare, and so, well, exceptional, that the code is, if not universal, than highly ubiquitous.

Today we will take a look at the first of the 3 P’s: the duty to protect.

A Series Side Note

As you read these three posts, the most pressing question in your mind (since we’re all ego-driven creatures) is likely, “How do I stack up to this criteria?†Even in modern societies where boys are taught that worrying about being a “real man†is silly, many men (and I’d venture to say most men) still want to think they make the cut.

If you identify with the 3 P’s, you’ll probably be nodding your head as you read along. If you don’t, you may experience a strong emotional reaction; we often feel a visceral, physiological fight-or-flight response to a “threat†to our social status.

It is a great truism that men will frame their definition of manhood in a way that most suits their own personal make-up, beliefs, and attributes; they gravitate to a definition of manhood that best describe themselves and criticize molds of manhood in which there is less alignment. Which is to say that a frail nerd is likely to downplay the importance of the protector role and emphasize the smarts needed to be a provider, while a physically fit man who can’t or doesn’t wish to have children is likely to downplay the procreator role and emphasize the strength needed to be a protector.

But defining manhood with yourself as the exemplar par excellence really isn’t the best way to go about it, is it? The kind of man I really respect is one who can frankly acknowledge where he may fall short of the traditional criteria, thoughtfully ponder whether that bothers him or not, and whether it’s a good standard in the first place. Then he can decide from there if it’s something he’d like to aspire more towards or whether he knows he doesn’t meet that traditional standard, but doesn’t really care either.

For example, I’m a real homebody who enjoys reading books and spending time with my wife and kids. Until recent times, this proclivity of mine would have gotten me labeled as a certifiable nancy boy (more on that below). But while getting out into the hurly burly of the world may not describe me personally, I can also understand the value of getting men into the public square to compete and to risk; all of society benefits from such strivings. I’m not going to completely change my ways because of this knowledge, but I’m not going to reject it out of hand either; it encourages me to look for ways to, if only slightly, temper my reticent habits with more social engagement.

All of which is to say, whenever you encounter standards of manliness that don’t fit you personally, fight the emotional knee-jerk reaction to dismiss them immediately, and spend more time thinking about their possible value, whether you might aspire more to them, and, if it is in fact impossible for you to achieve them, whether you might work harder for excellence in the other areas in which you can strive.

Man as Protector

“The quintessence of manliness is fearlessness, readiness to defend one’s own pride and that of one’s family.†–Julian Pitt-Rivers, The People of the Sierra

If we can think of the 3 P’s of Manhood as an arch through which a male must pass through to become a man, the imperative to protect is undeniably its cornerstone. The quality that is requisite for its fulfillment — courage — has been recognized as the sin qua non of manliness since ancient times. And it is also the male imperative that has most endured in our modern, otherwise gender-neutral world; even in households where work and parenting is shared equally between husband and wife, if something goes bump in the night, it will almost always be the man who is sent to investigate.

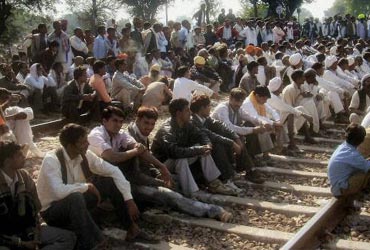

“Among the Jats living in the state capital of Chandigarh . . . courage and the willingness to take risks were the major values of the male and of manliness.”

The staying power and salience of protection as an imperative for manliness can be traced to the fact that, compared to the other two injunctions, it is rooted more firmly in anatomy and physiology. Men, in general, have greater physical strength than women; and in maintaining and growing a population, semen is much less valuable than a womb. Hence, being both stronger and more expendable, men have, since time immemorial, been given society’s dirtiest and most dangerous jobs.

“Manhood is a triumph over the impulse to run from danger.â€

As we shall see, Gilmore argues that all three of manhood’s core imperatives involve a degree of risk and are structured as win/lose propositions. The danger inherent in the protector role is simply more salient than that of the other two, since “losing†in this mission can result in bodily harm or death.

Because of the inherent risk in the endeavors required to become a man, “expendability…often constitutes the measure of manhoodâ€:

“To be men, most of all, they must accept the fact that they are expendable. This acceptance of expendability constitutes the basis of the manly pose everywhere it is encountered; yet simple acquiescence will not do. To be socially meaningful, the decision for manhood must be characterized by enthusiasm combined with stoic resolve or perhaps ‘grace.’ It must show a public demonstration of positive choice, of jubilation even in pain, for its represents a moral commitment to defend the society and its core values against all odds. So manhood is the defeat of childish narcissism that is not only different from the adult role but antithetical to it.â€

From being called to the battlefield in every era, to men putting women and children on the Titanic’s lifeboats while they went down with the ship, to men covering their girlfriend’s bodies during the Aurora movie theater shooting, manliness around the world has always meant a willingness to sacrifice one’s own life for the protection of others.

Standing Watch at the Door

“The real man gains renown by standing between his family and destruction, absorbing the blows of fate with equanimity.â€

The essence of the injunction to protect is the “need to establish and defend boundaries.†A man guards the line between dangers of all kinds and those he loves and feels duty-bound to protect — the boundary between his home and the outside world and that between his village or nation and its enemy. He is roused to action when that line is crossed. Even a man who doesn’t consider himself particularly patriotic or lend much credence to the concept of manhood might very likely find himself grabbing a rifle if invaders started pouring across the border of his country.

Bluff and Bravado

The boundaries a man protects extend past the physical variety to the line between honor and dishonor as well, both for his own reputation and that of his family and lineage. Traditionally, maintaining a reputation for manhood meant responding to any slight to either – protecting one’s good name was paramount.

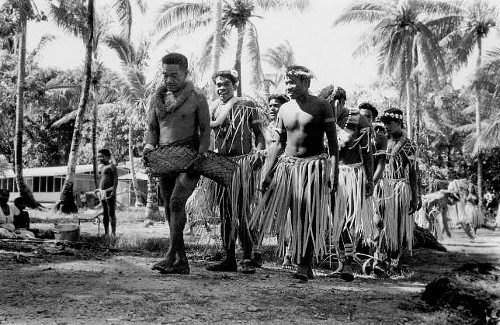

“After this protectiveness toward women comes the Trukese stress of fisticuffs and toughness. Young Trukese men feel they must battle each other to show bravery, to ‘vindicate manhood in physical combat.’ A man who absorbs insults is not a man at all. A common instigation to combat is to insinuate, ‘Come are you not a man?! I will take your life now.’â€

One of the key elements underlying all three of the P’s of Manhood is that a man’s fitness for each duty had to be demonstrated in visible symbols and accomplishments and had to be publicly confirmed. To be a reclusive homebody was considered effeminate – a man had to be out in the public square, “in the arena.†For example, in Cyprus, “a man who lingers at home with wife and children will have his manhood questioned: ‘What sort of man is he? He prefers hanging about the house with women.’” And among the Algerian Kabyle, “A man who spends too much time at home in the daytime is suspect or ridiculous: he is ‘a house man,’ who broods at home like a hen at roost.’ A self-respecting man must offer himself to be seen, constantly put himself in the gaze of others, confront them, face up to them (qabel). He is a man among men.”

“In Sicily, ‘un vero uomo’ (a real man) is defined by ‘strength, power, and cunning necessary to protect his women.’ At the same time, of course, the successfully protective man in Sicily or Andalusia garners praise through courageous feats and gains renown for himself as an individual. This inseparable functional linkage of personal and group benefit is one of the most ancient notions found in the Mediterranean civilizations.â€

When it comes to the protector role, this public demonstration of fitness takes the form of competitive, combative sports like wrestling and fisticuffs. These contests establish a pecking order within the tribe, showing who is the toughest. Success in a fight earns a man a reputation as someone who should not be messed with. At the same time, these dust-ups reveal which men are prepared for battle and which would be weak links should the tribe have to unite to face an external enemy. For each individual man contributes to the group’s overall reputation for strength, and that reputation can act as a deterrent that prevents enemies from even attempting an attack.

As Gilmore explains, using the frequent brawls engaged in by the young men of Truk Island as an example, the most important thing for men to demonstrate in these kinds of fights is his “gameness†– that even if he’s not the strongest of the bunch, he’s willing to scrap and endure:

“What seems to matter most is not winning the fight necessarily, although that counts, but rather the readiness to engage or to respond to challenge and the show of indifference to pain. A real man cares nothing about personal injury, laughing at the sign of his own blood. In fighting, win or lose, if he acquits himself bravely in the heat of combat, a man corroborates his claim to manhood, simultaneously bolstering his group’s reputation for strength. An honorable defeat is not itself a loss of face; what seems to matter most is to show a willingness to receive blows, to shed blood. Bruises and scars only add to a man’s prestige and that of his lineage.â€

While the bluff and bravado – overt machismo – that all-male groups exhibit is often criticized as being juvenile and theatrical, Gilmore argues that behaviors like brawling and risk-taking actually “overlay an infrastructure of serious social obligationsâ€:

“Beneath the posturing and the self-promotion lies a residue of practical expectations that men everywhere shoulder to some extent…the need to establish and defend boundaries.â€

“Being a man in Andalusia is also based on what the people call hombre. Technically this means manliness… hombre is physical and moral courage… it means standing up for yourself as an independent and proud actor, holding your own when challenged. Spaniards also call this dignidad (dignity). It is not based on threatening people or on violence, for Andalusians despise bullies and deplore physical roughness, which to them is mere buffoonery. Generalized as to context, hombre means courageous and stoic demeanor in the face of any threat; most important, it means defending one’s honor and that of one’s family… The restraint on violence is always based on the capacity for violence, so that the reputation is vital here.

How a Man Wrestles Is How He Does Everything Else

All of the 3 P’s interact and interrelate with each other. For example when it comes to the aforementioned public brawls, they are used by a man’s peers to judge not only his fitness as a protector, but how good of a farmer and husband he will be. The same qualities that make for a good wrestler – discipline and perseverance – are those that will make him a success in these other roles. A man who shows he can scrap will be more trusted and respected by his fellow men, and more likely to be asked by them to be a friend and a partner in economic pursuits. He’s the guy the other guys want when they’re picking teams. For similar reasons, the brawls are watched closely and enthusiastically by the opposite sex.

Physical prowess can thus win a man opportunities to gain material wealth (making him a better provider) and women (thus increasing his chances to procreate), thereby boosting his manly reputation overall.

Conclusion

The big question that will naturally arise from a discussion of the 3 P’s of Manhood (besides how well you personally embody them), is whether these standards are still relevant in a time where drones have replaced men as killing machines, some think the world is already overpopulated, and women make up half the workforce. Is manliness in fact obsolete?

As Gilmore points out, the imperatives themselves aren’t really bad or good as far as being categories of encouraged behavior. It’s how they’re applied, enforced, and segregated exclusively to the male sex that people take issue with. Some who are very traditional will say we should carry these charges forward pretty much untouched. Some will say they are offensive, sexist, and wholly outdated and should be dropped as markers of manhood altogether. And some (and this includes us) will say that they do still have value, and that you should retain the best parts of these manly duties, discard what doesn’t work, and not throw out the baby with the bathwater.

I actually respect someone who will take any of those particular sides more than someone who doesn’t want to have the discussion at all because “manhood is meaningless.†At least have the discussion. And when you do, now you know where to start.

Read the rest of the series:

Part II – Procreate

Part III – Provide

Part IV – The 3 P’s of Manhood in Review

Part V – What is the Core of Masculinity

Part VI – Where Does Manhood Come From?

Part VII – Why Are We So Conflicted About Manhood?

Part VIII – The Dead End Roads to Manhood

Part IX – Semper Virilis: A Roadmap to Manhood

____________

A Note on the Source

Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity by David D. Gilmore is a most excellent and insightful book. Like all authors, Gilmore has his biases, but for a subject like manhood that can often by covered so polemically, the book is refreshingly well-balanced.

The book came out in 1990 and Gilmore cites many anthropological studies that were done in the 60s and 70s. For the sake of style, we have used the present tense as he did when describing the cultures mentioned above. But obviously much has changed since those studies were done, and if any readers reside in the societies mentioned, it would be great to hear from them as to the current state of manhood where they live.

Actually, it would be great to hear from readers all across the world as to how their own culture sees manhood in our modern times.