Are men everywhere alike in their concern (and desire) for being manly?

Is the concept of manliness meaningless and entirely culturally relative?

For the last several weeks we have been exploring the answers to these questions by discussing the findings contained in Dr. David D. Gilmore’s Manhood in the Making.

Twenty years ago, Gilmore set out to conduct an exhaustive cross-cultural analysis of how masculinity is perceived and lived around the world.

What he discovered was that far from being exceptional and widely divergent, conceptions of what constitutes a “real man†have been common and consistent through time and around the world. A distinct code of manhood has not only been part of nearly every society on earth — whether agricultural or urban, premodern or advanced, patriarchal or relatively egalitarian — these codes invariably contain the same three imperatives; a male who aspires to be a man must protect, procreate, and provide.

As the subject is a fascinating and vital one, we have given each of these “3 P’s of Manhood†a thorough treatment. It was definitely a lot to take in; it’s really turned into a kind of Manhood 101 course! So today, for those who didn’t make it through the beastly posts, and for those who did but could use a quick re-orientation, today we’re providing a crib sheet that distills what we have covered thus far down to the basic fundamentals.

The 3 P’s of Manhood in Review

Protect

The essence of protection is the “need to establish and defend boundaries.” Boundaries create a sense of identity and trust. Should that line be crossed, men will spring into action. Men are called on to guard the perimeter between danger and safety, protecting tribe and family from predators, human enemies, and natural disasters.

A man adds to his individual honor by developing and demonstrating prowess in the protector role. At the same time, he bolsters his community’s reputation for strength as well, as the tribe’s overall reputation serves as a form of protection in and of itself — functioning as a deterrent to attack.

The protector role requires:

- Physical strength and endurance.

- Skill in the use of weapons and strategy.

- Courage – the ability to stand one’s ground, even when inwardly scared.

- Physical and emotional stoicism – an insensibility to physical pain and coolness under pressure.

- Voluntary, graceful acceptance of one’s expendability – a man glories in the fact he may have to lay down his life for his people.

- Public demonstration of one’s aptitude in the protector role, as shown through physical contests (wrestling, sparring, competitive sports). It is important not only to demonstrate strength and skill in these contests, but to show one’s gameness – that you’re a scrapper who’ll keep coming back for more even when battered.

Why men were historically given this role:

- Men have on average greater physical strength than women.

- Wombs are more valuable than sperm.

Procreate

The imperative to procreate essentially requires that a man act as pursuer of a woman, successfully impregnate her, and thus create a “large and vigorous family†that expands his lineage as much as possible.

The procreator role requires:

- Acting as the initiator in the seduction/courtship of women.

- Virility and potency – the ability to “get it up.”

- The ability to sexually satisfy a woman.

- Fecundity and having as many children as possible.

Why men were historically given this role:

- Higher testosterone and thus sexual drive.

- Ability to have numerous children and higher desire to spread seed.

Provide

The essence of provision is the ability to tame nature, to turn chaos into order, to take the raw materials of life and transform them into something of value. It involves, as Gilmore puts it, “purposive construction†— “commanding and assertive action that adds something measurable to society’s store.â€

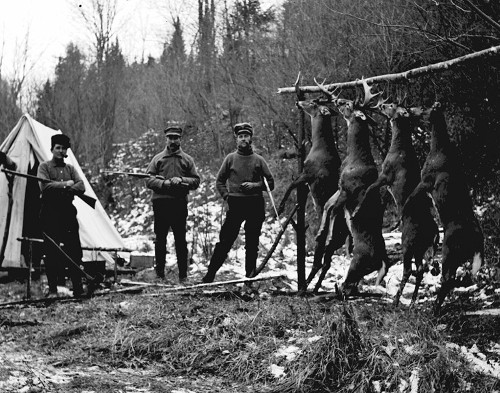

Hunting is the “provisioning function par excellence,†for it involves all the manly attributes (physical strength, mastery of tools, discipline and determination, initiative, etc.) and is a creative act that parallels battle, sport, and sex.

The provider role requires:

- Contributing the lion’s share of sustenance to one’s tribe/family (about a 70/30% split between husband and wife across times and cultures).

- Resourcefulness – cleverness, the ability to maneuver around obstacles, come up with creative solutions to problems, turn scarce resources into something of value.

- Becoming self-reliant – dependency is seen as shameful in a man, because he cannot be fully autonomous and provide for others if he is still dependent on his childhood family for care. It is seen as especially important to become independent of one’s mother.

- Being generous with your community – a man who does well for himself is expected to give back.

Why were men were historically given this role:

- Greater physical strength than women (hunting could be strenuous).

- More expendable than women (hunting could be fatal).

- Required journeying far from home (it would have been difficult for pregnant/nursing mothers and mothers with small children to undertake lengthy, arduous trips).

The Elements that Underlie the 3 P’s

There are several shared standards and necessary prerequisites that are common to all three of the P’s of Manhood:

- An earned status. Manhood is different from biological maleness, and it does not accrue to a man naturally through maturation. Rather it is a status of honor that must be earned through merit – by demonstrating excellence in the manly imperatives.

- Autonomy. Autonomy involves the “absolute freedom of movement†— “a mobility of action.†It means being able to make your own decisions, call your own shots, create your own goals, set your own pace, carve your own path. If restrictions are placed on the ability of man to strive for excellence in the 3 P’s, the chance to achieve manhood, and the existence of a true culture of manhood, disappears.

- Energy. A man is expected to overcome passivity, to always be up and doing, and to ceaselessly strive to achieve. A man is charged with taking the initiative in any endeavor, be it courtship or business.

- Danger and risk. All of the imperatives are set up as win/lose propositions. Risk may take the form of bodily harm or simply the blow to one’s manly reputation that comes from the failure to demonstrate competence in the standards of manhood. Most seriously, “losing†may mean losing one’s life. To win means gaining greater access to resources and the respect and honor of one’s fellow men and tribe. Mens’ greater amounts of testosterone fuel the desire to take these risks.

- Competition. Each of the manly roles involves competition between men to be the best – to bag the most game, accumulate the most wealth, give away the most wealth in the provider role; to marry the most wives, have the most kids, seduce the most women in the procreator role; to demonstrate the greatest strength, courage, mastery in the protector role. Men want to best their fellows, rise to the top, and be crowned with honor. Again, men’s higher testosterone fuels this drive to compete.

- Public affirmation. When it comes to excellence in the 3 P’s — talk doesn’t matter, results do. You have to put your money where your mouth is, and thus competence in all the manly pursuits must be demonstrated in the public square and affirmed by others. You must be willing to sally forth into the fray, to compete with other men, and show how you stack up against them. A man must be “in the arena.†For this reason a man who is a homebody, who avoids public contests, and desires to spend most of his time with wife and children is considered effeminate. As Gilmore puts it, “One wins or loses, but…one must play the game. The worst sin is not honest failure but cowardly withdrawal.â€

- Create more/consume less. The ultimate standard for each of the imperatives, and for the mantle of manhood itself, is to create more and consume less. To be a man is to demonstrate competence in the manly role – to pull one’s own weight, to be a contributor rather than a sponge, a boon rather than a burden to one’s people. This means adding to your tribe’s reputation for strength instead of detracting from it through physical frailty and cowardice, choosing fecundity over sterility, and providing something of value to society’s pot instead of only taking from it.

The Nature of the 3 P’s

The 3 P’s of Manhood emphasize and exaggerate the distinct biological potentialities of men, motivating them to channel that potential in service to the greater good.

The manly imperatives can be seen as having a dual nature and purpose: they are both civic duties and personal development pathways that (if the prerequisites above are met) simultaneously benefit both a man’s community and the man personally.

We’ll explore this dynamic and its implications in a modern world where manhood isn’t honored or valued in the final two posts in this series.

Manhood: A Three-Fold Path

Across cultures and time, the journey to manhood has been considered a three-fold path. Manhood can be viewed as a mighty edifice that must be built with three pillars of support. If one of the pillars is missing or weakened, too much stress is placed on the remaining pillars, twisting and contorting them.

For example, in a time where most men aren’t called upon to be protectors, and may have an unsatisfying, uncreative job, the procreator pillar (at least the sex part of it) can seem the only remaining way to demonstrate one’s manhood. Designed to be just one part of a man’s multi-faceted life, the pillar of procreation is forced to support much more weight than it was intended, turning sex into an unhealthy obsession.

Each of the pillars is important, and each interacts and interrelates with the others. For example, a man who demonstrates prowess as a protector can win the respect of his fellow men who then wish to partner with him in hunting/business, offering him the chance to become a better provider. And a man who is a better provider will attract more women, leading to the opportunity to become a procreator. The pillars cannot be completely separated either; a man will not be considered manly if he, say, fathers a brood of progeny, but fails to provide for them.

A failure to contribute in one or more of the manly imperatives is considered shameful, even if this failure is due to a disability or circumstance outside the man’s control. But a man can mitigate this shame if he seeks to find other ways to pull his own weight by striving for greater excellence in the charges in which he can contribute. For example, a frail man might still strengthen his tribe by developing technological innovations. An infertile man might work to become a mighty warrior or a matchless hunter. However he can, a man tries not to be a burden to others.

The greatest shame and scorn is reserved for a man who can’t, or won’t, strive in the pursuits of manhood – and doesn’t care either. He may denigrate the ideals of masculinity, evince indifference to the importance of a manly reputation, or attempt to move the goal posts on manhood to better match his own personal aptitudes and proclivities. For example, a man who is frail but has a keen intellect may say, “There’s nothing manly about being strong. That’s for dumb meatheads. A real man cultivates his mind.†Or a man who can’t, or does not want to have children may say, “What’s manly about being a dumb breeder? Any idiot can knock a woman up. A man knows what he wants, and I don’t want to ever have children.â€

An honorable man says, “I cannot contribute in this manly role, and I admit I fall short in this area of the manly code. But I understand why this standard is part of the code and I respect it. I will strive to be excellent where I can and seek to contribute in other ways.â€

Being A Good Man vs. Being Good at Being a Man

When anthropologist Michael Herzfeld made a study of the culture in a small village in Crete, he found that the men distinguished between two standards of manhood: being a good man and being good at being a man. The 3 P’s are the requirements of earning the latter designation.

Being a good man means living the “higher†moral virtues – having a virtuous character. Goodness involves seeking Beauty, Truth, Wisdom, and Justice, and being kind, honest, and true. It is about utilizing all of one’s human potential, achieving what the ancient Greeks called eudemonia – a truly flourishing life. Being a good man is not much different than being a good woman, and it is thus a definition that has more to do with how a man is different than a child, than how a man is different from a woman.

Being good at being a man means being able to perform the male role competently – to be a proficient protector, procreator, and provider, to be willing to take public risks, face danger, work hard, take action, compete fiercely, seek strength, and solve problems. It is focused on utilizing one’s distinctly masculine potential. Being good at being a man is both about how a man differs from a child and how he differs from a woman.

Being a good man is a philosophical category of manliness.

Being good at being a man is an anthropological category of manliness.

The first emerges from our minds — a desire to form an ideal.

The second emerges from the realities of biology, evolution, and the environment.

It is possible to be good at being a man, without also being a good man. For example a mob boss has a dangerous job, supports his family, and is highly resourceful. He also whacks people on a whim. He’s not a good man, but he’s good at being a man. He does actually live the 3 P’s. Which is why, even though we might not want to emulate him, we still can’t help but to think of him as pretty manly. Think Walter White for a modern pop culture example – audiences still wanted to root for him in spite of all the horrendous things he did (and wanted to lambast Skyler White for her desire to seek the truth and turn in Walt). The moral side of our brains tells us that he’s not a “real man†but at the gut-level we feel a degree of ancient, amoral respect.

While it’s possible to be good at being a man, without being a good man, as we shall see next time, the reverse is not true.

Conclusion and Onwards

In writing this conclusion, and all the posts in this series, I have struggled with whether to use the present or the past tense. On the one hand, what I have outlined here has been true in nearly every culture for thousands of years, and continues to be true in many cultures still today. On the other hand, these tenets of the ancient code of manhood are greatly challenged, changed, and criticized in the modern Western world. But because our modern society represents such a tiny blip in the grand sweep of history, and because there are still strong echoes of this code even today, I ultimately decided to use the language of the present in this piece.

At the start of this series, I wrote that in our current culture some people think manliness is altogether meaningless, and some recognize its reality but fall into one of three camps: 1) the code of manhood should continue on much as it has for thousands of years, 2) the code of manhood is offensive/damaging/irrelevant and should be dropped altogether, or 3) there are some parts of the code that should be retained, while others should be jettisoned.

Hopefully, the first three articles in this series have shown that the first contention – the idea that manliness is meaningless – is thoroughly untenable.

Before you decide where you fall as to the three other possible positions, come along for the last three articles in the series. Here’s where Manhood 101 is going next:

- What is the core of masculinity?

- Where does manhood come from and why has it disappeared?

- Why should you be a man even today?

Read the rest of the series:

Part I – Protect

Part II – Procreate

Part III – Provide

Part V – What is the Core of Masculinity

Part VI – Where Does Manhood Come From?

Part VII – Why Are We So Conflicted About Manhood?

Part VIII – The Dead End Roads to Manhood

Part IX – Semper Virilis: A Roadmap to Manhood