Welcome back to our series on the spiritual disciplines, which explores exercises that can be used to train the soul. The purposes and practices of these disciplines are approached in such a way that they can be adapted across belief systems.

When you hear the word “study,” you probably associate it with your school days — with poring over textbooks, trying to comprehend new concepts, and memorizing facts.

Close reading, critical analysis, and memorization all have something to do with study as a spiritual discipline as well, but they’re marshaled for a very different purpose.

Rather than trying to understand what a subject means generally, the spiritual studier seeks to know what something means for him.

Rather than cramming for a test — filling one’s head with facts that are quickly regurgitated and just as soon forgotten — the spiritual studier aims to deeply absorb knowledge and make it a permanent part of his soul.

And instead of being limited to the study of written texts, the spiritual studier also examines himself — a related exercise that also constitutes a distinct discipline.

Today we will explore both of these exercises — the study of text and the study of self — as ways of training the soul. As you’ll hopefully come to see, their practice can be far more compelling and rewarding than any of the homework you ever did in school.

[aesop_chapter title=”The Spiritual Discipline of Study” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads/2017/09/reading-by-fire-copy.jpg” video_autoplay=”on” bgcolor=”#888888″ revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

What Is the Purpose of the Spiritual Discipline of Study?

“The purpose of the Spiritual Disciplines is the total transformation of the person. They aim at replacing old destructive habits of thought with new life-giving habits. Nowhere is this purpose more clearly seen than in the Discipline of study. . . . The mind is renewed by applying it to those things that will transform it.” –Donald S. Whitney

It’s often been said that a man’s thoughts determine his reality.

But how does he change his thoughts in order to change his life?

As we’ve often advocated, one of the best ways of changing your internal life, is by changing your external one: in taking action, your thoughts shift to match the new reality created by your behavior. Indeed, it can often be easier to change from the outside in, than from the inside out.

But that simply throws us back onto another question: How do you decide what actions to take in the first place?

The truth is that thought and action are inextricably tied, and cannot be separated. This is true on a couple of levels.

First, action and thought form a loop, in which each vitally feeds on the other. Study provides insight on what actions to take; experience then tests the real-world validity of these abstract ideas, and informs one’s future study. Action. Reflection. Action. Reflection.

Second, study and thought should not be understood as entirely passive practices, but — especially when engaged in with mindfulness, direction, and deliberation — as actions in and of themselves. Certainly, study is an action in that it produces an equal and opposite reaction; when you apply your mind to something, it shapes you right back.

Richard Foster puts it this way in Celebration of Discipline:

“Study is a specific kind of experience in which through careful attention to reality the mind is enabled to move in a certain direction. . . . [T]he mind will always take on an order conforming to the order upon which it concentrates.

Perhaps we observe a tree or read a book. We see it, feel it, understand it, draw conclusions from it. And as we do, our thought processes take on an order conforming to the order in the tree or book. When this is done with concentration, perception, and repetition, ingrained habits of thought are formed.â€

Whatever we pay attention to is our reality.

The spiritual discipline of study takes seriously this fact, calling us to be intentional in choosing the things on which we wish to focus, and challenging us to plumb them more deeply. Because while giving any level of attention to something will change you in return, you can control the profundity of this “ricochet†effect: The more intensely you study something, the more your mind will “conform to the order upon which it concentrates.â€

Ultimately, the purpose of the spiritual discipline of study is to take knowledge on the long journey from head to heart — to incorporate it into the marrow of our bones, so that it not only alters our thought patterns, but transforms the contours of our entire self and how we act in the world.

What Things Can Be Spiritually Studied?

Anything, from books to behavior to natural phenomena, can be studied — that is, rigorously focused on and examined.

In terms of spiritual study, nature is one fruitful subject (of which Thoreau offers abundant instruction). As we’ll unpack below, the self is a rich vein for spiritual study as well.

Even the news can be worthwhile fodder for spiritual examination. Foster argues that it behooves us to “meditate upon the events of our time and to seek to perceive their significance,†even arguing that “We have a spiritual obligation to penetrate the inner meaning of events†in order “to gain prophetic perspective.†(Keep in mind that while we typically think of “prophesy†in terms of foretelling, it also concerns interpretation and the gaining of insight.)

Of all the sources of study, written texts are of course the medium we most associate with the practice, and we’ll dedicate the first half of this piece to how one can attend to them more fully.

What Texts Are Worth Studying?

“The key to every man is his thought. Sturdy and defying though he look, he has a helm which he obeys, which is the idea after which all his facts are classified. He can only be reformed by showing him a new idea which commands his own.†–Ralph Waldo Emerson

Given the purpose of the spiritual discipline of study outlined above, not all books and articles are obviously suited for the task.

Religious scriptures are the most natural source of fodder for spiritual study, and adherents of many faiths will typically say they are the most important thing to apply one’s mind to.

But there are other texts that reward close, spiritually-oriented study as well.

Ralph Waldo Emerson has some excellent recommendations on this front. When he presented a list of what he considered must-read books to an audience of young college students, he suggested studying many of the Western canon’s “secular†classics in order to build the intellect. But he also argued that certain books were vital for the education of the soul.

First among these was that “class of books which are the best: I mean the Bibles of the world, or the sacred books of each nation, which express for each the supreme result of their experience.†Here Emerson listed the Hebrew Bible, the Christian New Testament, the Zoroastrian Desatir, various Buddhist writings, the Confucian Four Books and Five Classics, and the Hindu Vedas, Upanishads, Vishnu Purana, and Bhagavad Gita.

In addition to these more obvious religious texts, however, he also recommended “such other books as have acquired a semi-canonical authority in the world, as expressing the highest sentiment and hope of nations.†These included the Stoic writings of Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, the works of Indian author Vishnu Sarma, The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis, and Pascal’s collection of “Thoughts.â€

Emerson further commended for closer and more intuitive study anything with “the imaginative element†and a certain “richness†that “leave[s] room for hope and for generous attempts.†That is: “Every good fable, every mythology, every biography out of a religious age, every passage of love, and even philosophy and science, when they proceed from an intellectual integrity, and are not detached and critical.†Such works included:

“The Greek fables, the Persian history, the ‘Younger Edda’ of the Scandinavians, the ‘Chronicle of the Cid,’ the poem of Dante, the Sonnets of Michel Angelo, the English drama of Shakespeare . . . and even the prose of Bacon and Milton, — in our time, the ode of Wordsworth, and the poems and the prose of Goethe.â€

“All these books,†Emerson notes, “are the majestic expressions of the universal conscience, and are more to our daily purpose than this year’s almanac or this day’s newspaper.â€

Emerson’s list is certainly not meant to be definitive. There are many more texts that “have the imaginative element†and “leave room for hope and for generous attempts†(including Emerson’s own!). Anything that feels “devotional†in nature, that offers elevation and inspiration, that challenges our assumptions, that helps us see life in a different way, that explicates myth and archetype — anything that contains an element of profundity and expands the soul — can be on the table for spiritual study.

The apostle Paul offers a good rule of thumb here: “whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable — if anything is excellent or praiseworthy — think about such things.†Emerson adds another helpful guideline, arguing that texts which bear spiritual study should feel as though “they are for the closet, and to be read on the bended kneeâ€:

“Their communications are not to be given or taken with the lips and the end of the tongue, but out of the glow of the cheek, and with the throbbing heart. Friendship should give and take, solitude and time brood and ripen, heroes absorb and enact them. They are not to be held by letters printed on a page, but are living characters translatable into every tongue and form of life.â€

While these general guidelines definitely don’t exclude studying texts we disagree with, if their arguments are forwarded in constructive ways, we would also do well to remember this Nietzschean maxim: “if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.â€

What Is the Difference Between Reading and Studying?

The spiritual discipline of study involves more than simple reading, and that difference goes beyond what you read. Just because you’re reading the Bible, doesn’t mean you’re studying it.

Studying differs from reading in the degree of deliberation, immersion, and focus you bring to the text. Reading is about breadth, while study is about depth. To borrow an analogy from The Shallows, reading is like crossing a lake on a jet ski, while studying is like scuba diving below the surface. In the first instance, we want to see as much of the landscape as possible; in the second, we’re deliberately hunting for treasures below.

Spiritually-oriented study also differs from reading (and “secular†study) in regards to your intentions. You’re not just reading for information or entertainment, but for discernment. You’re seeking to know not just what a text means generally, but what it means for you. You’re open to the idea of it influencing your decisions, your ideas about life, and how you think you should act.

Study is essentially disciplined reading. In a time where we’re prone to distraction, and used to scanning and skimming, it requires an inner muscle that’s typically atrophied from disuse.

Which makes it all the more worth exercising.

How Do You Practice the Spiritual Discipline of Study?

“There is no thought in any mind, but it quickly tends to convert itself into a power.†–Ralph Waldo Emerson

The spiritual discipline of study involves the practices typical of any kind of study, alongside a uniquely meditative element. Critical analysis and contemplation work together to allow the practitioner to dive deeper into the text: search and scrutiny pull forth insights, while meditation extracts further marrow, allowing it to be personalized and internalized.

The practices outlined below incorporate both edges of this blade.

General Tips

- Block distraction. With our screens beckoning, it can be hard to do any “deep work†these days. Consider reading an “analog†copy of the text you want to study. If reading on your phone, use apps that block you from using other apps.

- Highlight/underline. Studying with a pen or marker in hand keeps you more focused on the text, and heightens your expectations of finding a nugget of wisdom within it.

- Take notes. Scribble in the margin, or dedicate a notebook to your spiritual studies. Write down your insights and questions as you read.

- Check cross-references/footnotes. When something confuses you or just catches your attention, check out the cross-references to that scripture verse, the footnote to that sentence.

- Look up words you don’t know/want to know more about. When reading scriptures, see where else a certain word is used, find out the etymology, and look how its rendered in other translations.

- Outline the chapter. Or try to write a summary of it in your own words.

- Think about it yourself first, before you turn to a commentary. See what angles and insights you can come up with on your own, before you reach for the predigested answers of experts. Be self-reliant.

- Read a passage multiple times. Especially if you feel like you’re not getting it. But even if you think you do get it, you’ll discover new things with each pass, and the more you read it, the more it will become ingrained on your soul.

- When your mind wanders, gently bring it back to the text. Don’t get frustrated. It happens.

Take Time to Reflect, Contemplate, and Absorb

Do you ever close a book and shortly thereafter realize you can hardly remember anything of what you just read? The information passed through your mind like water through a sieve.

It’s this phenomenon that leads people to think they’re not good readers, and that the discipline of study isn’t compelling and worthwhile, leaving them as it does so “dry†and unchanged.

In Spiritual Disciplines for the Christian Life, Donald S. Whitney offers the following analogy to explain that the real root of the issue isn’t in the person himself, or the discipline of study, but in how the reader is going about it:

“Imagine that you’ve been outside on an icy day and then come inside where there’s a hot, crackling fire in the fireplace. As you walk toward it, you are very cold. You stretch out your hands to the fire and rub them together briskly during the two seconds it takes to walk past the glow and the warmth. When you reach the other side of the room, you realize, I’m still cold. Is there something wrong with you? Are you just a second-class ‘warmer-upper’? No, the problem isn’t you; it’s your method. You didn’t stay by the fire. If you want to get warm, you have to linger by the fire until it warms your skin, then your muscles, then your bones until you are fully warm.â€

If you rapidly pass over one line in a book after another, never pausing to consider what you’ve read, its words never have a chance to warm you. You’ve got to linger by the heat — taking the time to really ponder what you’re studying.

As you read, pay attention to what impresses your mind or arrests your attention.

Is there a line or paragraph that feels profound, that stirs you inside? Does something you read seem to tangibly expand your mind and soul? Reflect on why this sentence or section is provoking that effect. Do you see a signpost pointing in a certain direction? Is there an invitation somewhere in these words?

At the same time, also consider places that make you feel a sense of discomfort or “resistance.†Reflect on why a section subtly repels you. Does it convey something you genuinely disagree with? Or does it remind you of a duty or desire you know you should fulfill but are stubbornly resisting?

Reflecting on how to apply what you’re studying to your life is crucial. How can you put what you’re learning into practice? How should the insights you’re uncovering change how you see your life, the decisions you make, and your habits?

Reflection and contemplation shore up the holes in the sieve of your mind, allowing you to better understand, absorb, and retain the knowledge you study. And the better it’s absorbed, the more it can transform you.

Use Your Imagination to Enter Into the Text

If what you’re reading includes stories, greater engagement with it can be found by using your imagination to immersively “enter†into the text. Place yourself in a scene, and imagine what each of your senses would be experiencing. As Foster suggests in reference to the Gospels, “Smell the sea. Hear the lap of water along the shore. See the crowd. Feel the sun on your head and the hunger in your stomach. Taste the salt in the air. Touch the hem of his garment.â€

You might choose not just to imagine yourself as a bystander in a story’s scene, but to participate in it, embodying the roles of certain characters. Alexander Whyte explains this exercise: “with your imagination anointed with holy oil, you again open your New Testament. At one time, you are the publican: at another time, you are the prodigal . . . at another time, you are Mary Magdalene: at another time, Peter in the porch. . . . Till your whole New Testament is all over autobiographic of you.â€

By imaginatively immersing yourself in a story, you can notice details and insights that you would have otherwise missed in reading it “clinically.†In an interview he did for On Being, Father James Martin, a Jesuit priest, gave a salient example of what these little discoveries can look like:

“I did a meditation with a group a year or two ago. And it was the multiplication of the loaves and the fishes. And in one of the stories, where Jesus multiplies the loaves and the fishes, and feeds the crowds, there’s a little boy who brings five barley loaves and two fish. And, this one woman in this group I was facilitating, said I never noticed that little boy. She said, I’ve read this story probably hundreds of times, and heard it at Mass, and I never knew he was there. And she said, I spent time just looking at him and noticing how he was able to bring what little he had to Jesus. And that was her insight.â€

Though the above examples center on imaginatively entering the stories of the New Testament, this same practice of course works with any stories and myths.

Meditate on a Word or Phrase

When you think about meditation, you likely think of the Eastern tradition, in which the goal is to empty the mind. But there is another version, in which one seeks to fill the mind. Rather than trying to detach the mind from all desire and distraction, you attempt to attach it to something good.

If a word, phrase, or concept “lights up†for you as you read something, pause to meditate on it. Keep repeating it to yourself or out loud. Whitney offers another salient analogy here: if reading quickly is like bobbing a tea bag in and out of a cup of hot water, this kind of meditation is akin to letting the tea bag sit and steep. You let the words percolate in your mind, releasing their insights into your soul.

How long should you engage in this kind of meditation?

In his Spiritual Exercises, St. Ignatius advises that “If one finds . . . in one or two words matter which yields thought, relish, and consolation, one should not be anxious to move forward, even if the whole hour is consumed on what is being found.â€

Memorize Quotes/Verses/Poems

The practice of memorization — once a fundamental of learning — has fallen out of favor in the internet age. We figure if we want to know something, we’ll just Google it. But when something is stored in an external brain, it doesn’t stay at the top of our own; when it’s embedded in the “cloud,†it isn’t ingrained in the marrow of our bones. And it simply isn’t accessible when our devices aren’t available.

Something special happens when you learn something by heart. Think about that phrase — by heart. When you memorize a favorite quote/verse/poem, it becomes a part of you. Your understanding of it deepens. Your conviction of its message strengthens.

Plus, memorizing quotes/verses/poems puts them at our disposal anytime, anywhere. When you’re wrestling with a temptation or hard decision, or struggling to maintain your equanimity in the face of a setback, you can recite a backbone-strengthening line to yourself. When a friend needs advice, you’ll have some powerful words at the ready. (It often helps to put things in your own words, of course, but how often have you read or heard something and thought, “That’s put perfectly — better than I ever could have; I need to remember these words exactly and convey them to my friendâ€?) When you have downtime — when you’re driving to work, or waiting in line, or lying in bed at night — a treasury of memorized quotes gives your mind somewhere uplifting to go. A strengthening citadel to visit. At all times, and in all places, you can meditate on what you’ve learned by heart, thereby renewing your heart.

Study With Humility and Persistence

Two of things that most lend themselves to success with the spiritual discipline of study are more attitudes than practices: humility and persistence.

You must approach spiritual study with humility in the sense of being open to the idea that what you read may change you. That if you encounter something that feels like Truth with a capital T, you are willing to adjust your thoughts and actions to align with it.

You must also approach study with proper expectations. Though following the methods outlined above will make your study sessions more engaging and increase the chances of your receiving a fresh insight, studying will not always be an ecstatic or moving experience. You will not always get a charge or feel a sense of peace. Often, you won’t feel much at all. But that doesn’t mean that your studying isn’t having an effect; whether perceptibly or not, seeds are being planted that will eventually bear fruit — especially when they’re nourished by other spiritual disciplines.

So stick with spiritual studying, even when you don’t feel like it, trusting that the breakthroughs you seek will eventually come.

[aesop_chapter title=”The Spiritual Discipline of Self-Examination” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads/2017/09/mirror.jpg” video_autoplay=”on” bgcolor=”#888888″ revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

While written texts can be a rich vein for study, so is your own life.

Such a study has proved compelling for thousands of years. One of the most famous maxims of the ancient Greeks was “know thyself.â€

Yet for as long as this injunction has existed, it has been widely ignored.

Indeed, most of us, though we may protest to the contrary, don’t really want to know ourselves well. We don’t want the left hand to know what the right is doing; we don’t want to look under the hood and examine our motivations, habits, and behaviors too closely. For doing so can be a rather unsettling affair.

We fear that in acknowledging our weaknesses, our hearts will be pricked to amend them.

We fear that in countenancing our ignored desires, we’ll feel prompted to fulfill them, or sorrowed with regret.

We fear to learn that we are other than who we think we are.

It’s much easier to let our day-to-day lives pass in a blur, to hide some parts of ourselves from other parts, to watch ourselves go by through a hazy, and flattering, lens.

Truly, it takes real courage to honestly confront what is and is not true about yourself — to regularly take a good, hard look in the mirror. But committing to do so, through the spiritual discipline of self-examination, is an eminently worthwhile endeavor.

What Is the Purpose of the Spiritual Discipline of Self-Examination?

“The superior man will watch over himself when he is alone. He examines his heart that there may be nothing wrong there, and that he may have no cause of dissatisfaction with himself.†–Confucius

The discipline of self-examination is like a diagnostic test for the soul.

It utilizes self-dialogue for the purpose of self-accountability (and, if one so believes, accountability before God). It tasks you with conducting an internal interview that aims to strip away rationalizations, denials, and blind spots, in order to gain an accurate perspective of who you are, how you act, and what you want. Motivations are scrutinized; biases unearthed; weaknesses confronted. The temptation to cast blame is reined in. Habits are assessed as to whether they are adding to, or detracting from, your life and aims.

The goal of this self-examination is not simply to gain greater self-awareness, but to take action on the “data†that is gathered. Weaknesses are identified in order to be corrected. Worthy desires are recognized so plans can be made for their fulfillment. Bad habits are acknowledged so they can be jettisoned; good ones are noted so they can be enhanced.

The ultimate purpose of self-examination then, is to know thyself, in order to better thyself — to live closer to one’s own ideals and/or divine purpose.

How Do You Practice the Spiritual Discipline of Self-Examination?

“The mind must be called to account every day.†–Seneca

“Finding yourself†or “knowing yourself†are vague buzz phrases that sound good in the abstract, but are harder to put into practice. Too often, the process of knowing oneself is left to spontaneous navel-gazing — a thinking process that moves in fits and starts and invariably dissipates into a vaguely emotional, but content-less fog.

For the pursuit of self-knowledge to be effective, it requires concrete structure and direction.

This begins with narrowing the focus of examination. Rather than considering the entirety of one’s life, which is generally too large and unwieldy to get a handle on, you simply review each day. Looking at your daily habits gives you something specific and graspable to audit, and when taken together, these discrete blocks will ultimately reveal macro insights and larger patterns in your life.

In order to keep even these daily reviews from being too vague in result, and to build a collection of consistent data that can be effectively mined for such patterns, it’s best to hone the focus even further, by asking yourself the same set of questions every single day.

The wording and form of these daily self-dialogue questions can vary; below are several examples of the structure they can take.

The Stoic Self-Examination

The spiritual discipline of self-examination goes all the way back to the ancient philosophers of Greece and Rome.

One of its earliest iterations can be found in the Golden Verses of Pythagoras:

“Do not welcome sleep upon your soft eyes

before you have reviewed each of the day’s deeds three times:‘Where have I transgressed?

What have I accomplished?

What duty have I neglected?’Beginning from the first one go through them in detail, and then,

If you have brought about worthless things, reprimand yourself,

but if you have achieved good things, be glad.â€

Later, the Roman philosopher Quintus Sextius drew on this Pythagorean practice to create his own self-examination, which the Stoic Seneca described and commended in his writings:

“This was Sextius’s practice: when the day was spent and he had retired to his night’s rest, he asked his mind:

Which of your ills did you heal today?

Which vice did you resist?

In what aspect are you better?Your anger will cease and become more controllable if it knows that every day it must come before a judge . . .

I exercise this jurisdiction daily and plead my case before myself. When the light has been removed and my wife has fallen silent, aware of this habit that’s now mine, I examine my entire day and go back over what I’ve done and said, hiding nothing from myself, passing nothing by.â€

“Twice a day, or at least once, make your particular examens. Be careful never to omit them. So live as to make more account of your own good conscience than you do of those of others; for he who is not good in regard to himself, how can he be good in regard to others?†–St. Francis Xavier

As part of his Spiritual Exercises, St. Ignatius created a form of prayer known as the “examen†(often today called the “examination of consciousnessâ€), that is done at least once a day — typically in the evening.

Both divine petition and personal audit, Ignatius formulated the examen as a five-point process:

“The First Point is to give thanks to God our Lord for the benefits I have received. The Second is to ask grace to know my sins and rid myself of them. The Third is to ask an account of my soul from the hour of rising to the present examen, hour by hour or period by period; first as to thoughts, then words, then deeds, in the same order as was given for the particular examination. The Fourth is to ask pardon of God our Lord for my faults. The Fifth is to resolve, with his grace, to amend them. Close with an Our Father.â€

In summary, the steps of the examen are: 1) express gratitude, 2) acknowledge your sins, 3) review how you spent your time since the last examen, 4), ask for forgiveness for your sins, 5) ask for grace to amend them.

In The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything, Fr. Martin notes that it’s okay to tweak the examen to your own needs. For example, he personally finds it “hard to identify sinfulness without first reviewing the day†and “easier to ask for forgiveness after thinking about my sins.†So in doing his examen, he rearranges the steps a bit, so that it goes like this:

“1. Gratitude: Recall anything from the day for which you are especially grateful, and give thanks.

2. Review: Recall the events of the day, from start to finish, noticing where you felt God’s presence, and where you accepted or turned away from any invitations to grow in love.

3. Sorrow: Recall any actions for which you are sorry.

4. Forgiveness: Ask for God’s forgiveness. Decide whether you want to reconcile with anyone you have hurt.

5. Grace: Ask God for the grace you need for the next day and an ability to see God’s presence more clearly.â€

Some notes on a few of these steps:

First, when you express gratitude, don’t just think of the big, obvious things that happened during the day, but also the small, subtle, surprising things that made you smile or warmed your heart.

Second, Fr. Martin calls the review step “the heart of the prayer,†and offers helpful detail as to what it consists of:

“Basically you ask, ‘What happened today?’ Think of it as a movie playing in your head. Push the Play button and run through your day, from start to finish, from your rising in the morning to preparing to go to bed at night. Notice what made you happy, what made you stressed, what confused you, what helped you be more loving. Recall everything: sights, sounds, feelings, tastes, textures, conversations. Thoughts, words, and deeds, as Ignatius says.â€

While you think you know how your day went, the truth is that you hardly examine, and thus understand, anything about it at all. It’s just a blur. By really taking the time to review everything you did/felt/experienced each day, you can learn so much more about how you use (or don’t use) your time and how your schedule flows (or doesn’t). You’ll find that certain themes — certain hopes, problems, issues, feelings, doubts, and frustrations — repeat themselves. You can begin to discern patterns you otherwise never would have recognized: highs and lows that occur at roughly the same times each day; bad habits that are having a domino effect that sabotages your goals; moments that bring you joy that could be further extended.

To better uncover these data points during the review segment of the examen, consider asking yourself these additional questions suggested in the Spiritual Disciplines Handbook:

- When today did I have the deepest sense of connection with God, others, and myself? When today did I have the least sense of connection?

- What was the most life-giving part of my day? What was the most life-thwarting part of my day?

- Where was I aware of living out of the fruit of the Spirit? Where was there an absence of the fruit of the Spirit?

- What activity gave me the greatest high? Which one made me feel low?

As insights and patterns emerge from your daily reviews, you’ll need to decide how best to attend to them — to solidify the positive, and turn around the negative.

Third, when you think of your mistakes, identify not just the sins of commission — things you actively did wrong — but those of omission: those things you could have done but didn’t — the times you could have bothered, but decided not to. Most of us aren’t committing grievous sins on a day-to-day basis, but we all have places where we could have done better, where we “turned away from any invitations to grow in love.†Did you lose your temper with your children? Did you only half-listen when a friend engaged you in conversation? Did you fail to give due credit to a co-worker?

Finally, Fr. Martin notes that “The daily examen is of special help to seekers, agnostics, and atheists,†who can easily alter the steps and turn it into a “prayer of awarenessâ€:

“The first step is to be consciously aware of yourself and your surroundings. The second step is to remember what you’re grateful for. The third is the review of the day. The fourth step, asking for forgiveness, could be a decision to reconcile with someone you have hurt. And the fifth is to prepare yourself to be aware for the next day.â€

Whatever exact form your examen takes, write it down on a notecard or in a journal and place it beside your bed. At night, turn off your phone, pick up the card, and work your way through the five steps. Perform the exercise mentally, or if you desire, journal your reflections.

As you engage in the examen consistently, you’ll soon begin to live with more gratitude, identify what habits bring life or death to your soul, and awake each morning committed to doing better than you did the day before.

Benjamin Franklin’s Virtue Chart

While the iconoclastic Benjamin Franklin wasn’t much for organized religion and theological dogma, he did, his biographer Walter Isaacson notes, have an absolute “passion for virtue.†And he ardently believed it was nearly impossible to cultivate that virtue without some kind of structure by which to train the soul.

Franklin personally sought that structure by creating his own system of self-examination.

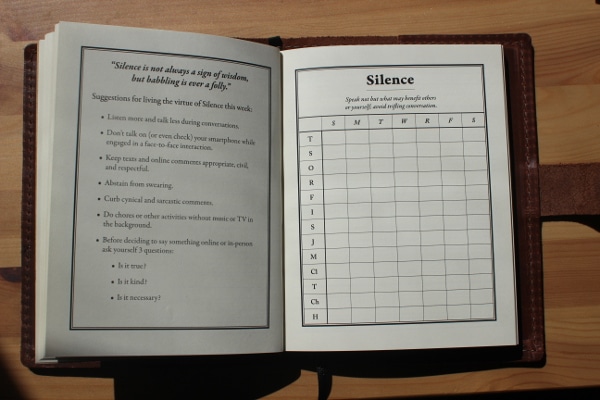

Committed to the idea of continual moral improvement from a young age, when he was twenty years old he conceived of a program that would keep him accountable in his quest to cultivate virtuous habits. Ever the ethical pragmatist, he drew up a list of 13 virtues he wished to develop:

- Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.

- Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.

- Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.

- Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.

- Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing.

- Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.

- Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

- Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.

- Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.

- Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, clothes, or habitation.

- Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.

- Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation.

- Imitate Jesus and Socrates.

Franklin also created a chart on which to keep track of his progress in living each of these 13 virtues. Each week he would specifically focus on one virtue while also keeping track of the others.

When Franklin failed to live up to the virtues on a particular day, he would place a mark on the chart. When he first started out on his program, he found himself putting marks in the book more often than he wanted. But as time went by, he saw the marks diminish.

After a week of examining his particular adherence to one of the virtues, Franklin would then move on to the next, eventually going through four cycles of each of the virtues in a single year.

In addition to tracking his virtuous habits each day, Franklin also asked himself two questions to focus his mind on doing good in the world.

In the morning, he would ask himself:

What good shall I do this day?

This reflection helped Franklin focus on things he could do to serve his fellow man and benefit his society as he went about his daily routine.

Then in the evening, he would return to the question by asking himself:

What good have I done today?

Franklin examined how he had spent his hours and whether he had done the good deeds he had planned on doing, as well as if he had taken action on unforeseen opportunities to lend others a helping hand.

If you’re interested in following Franklin’s self-improvement/examination program, we’ve re-created his virtue charts and good deed prompts as a leather-bound journal.

The ultimate goal of Franklin’s two forms of self-examination — his virtue tracking and good deed prompts — was to obtain to “moral perfection.†And though he fell short of this lofty ambition, he still felt the effort had greatly improved his life and been thoroughly worthwhile:

“Tho’ I never arrived at the perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far short of it, yet I was, by the endeavour, a better and a happier man than I otherwise should have been if I had not attempted it.â€

Putting the Discipline of Self-Examination Into Practice

Did one of the self-examination methods outlined above resonate with you? Adopt it as the form of your personal self-examination practice. Or create your own. You can readily come up with your own list of daily self-dialogue questions, or a list of virtue/good deeds you wish to accomplish each day.

Whatever form of self-examination you choose, use it consistently. It’s easy to say you’ll contemplate your day and your actions each night in the absence of any structure, but your mind will wander, and then you’ll fall asleep.

Life usually doesn’t have big signposts and pivot points; rather it moves in tiny dribs and drabs. If you don’t have a way to keep track of them, it becomes difficult to know if you’re regressing or progressing.

Having a set list of questions to review will focus your intentions, helping you recognize where you’re struggling, where you’re doing well, and patterns in your habits.

By forcing you to stop hiding yourself from yourself, and to confront the specifics of how you’re really doing, you can start taking action to address your weaknesses, facilitate your strengths, and get a little better every day.

Read the Other Articles in the Series

An Introduction

Study & Self-Examination

Solitude & Silence

Simplicity

Fasting

Gratitude