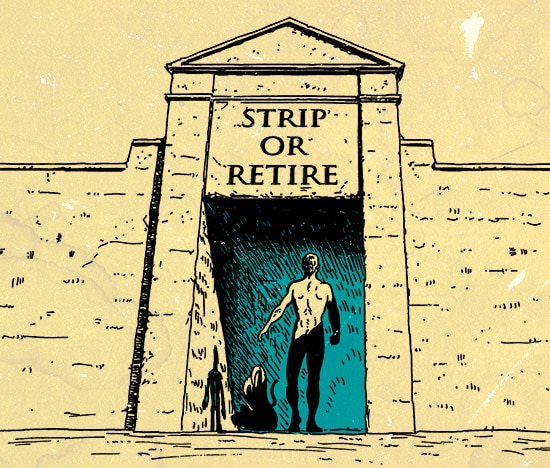

Over the entrance to a small paelstra –– a wrestling school — in ancient Greece was emblazoned this short phrase: Strip or Retire.

During this period, men competed in sports and exercised in the nude. Thus the inscription served as a challenge to each man entering the gymnasium: come in, participate, and struggle — or keep out. Mere spectators were not welcome.

To be part of this wrestling school, you were literally required to put your skin in the game.

In antiquity, such a requirement extended far beyond athletics; a man could not participate in civic life, business transactions, war, or philosophical debates unless he had metaphorical skin in the game — unless he was willing to risk his life, and what was even more valuable, his honor.

Honor and Skin in Antiquity

In classical honor cultures, a man’s honor centered on his reputation — a reputation that had to be proven and tested in the public arena. To be taken seriously, you had to show your face to others, and be open to constant challenges to your credibility. Whether or not your words and reputation could be backed up was never permanently decided and was instead constantly open to question. As Dr. Carlin Barton puts it in Roman Honor, participating in the everyday life of ancient Rome required that “one gambled what one was.” The level of risk you accepted in your actions and words directly correlated to their weight and power and the degree of respect your peers bestowed on you. The more risk you incurred, the more you showed yourself to be invested in what you said, the more status and trust you earned.

It’s for this reason that Roman orators would often open their tunic to reveal the scars they had earned in battle; these tangible badges of honor served as irrefutable appeals to their authority and ethos. Scars showed an audience a man had been in the arena — that he wasn’t advocating for others to take risks he was unwilling to undertake himself. His bonafides were indisputable: the skin he had literally sacrificed in the fight.

As Barton explains, the ancient Romans were in fact so invested in maintaining their honor, they were willing to kill themselves to verify their words:

“The Romans judged the weight of a person’s word not against an abstract standard of truth but how much was risked in speaking; they considered the stakes (the sacramentum, the ‘deposit’ or ‘forfeit’ that backed up one’s words). Words had weight when the speaker’s reputation, persona, fama, nomen, life were risked in speaking. When Vitellius refused to believe the intelligence reports given him by the centurion Julius Agrestis, the latter declared, ‘Since you require some decisive proof…I will give you a proof that you can believe.’ He slew himself on the spot, thereby, according to Tacitus, confirming his words. When a common soldier arrived at camp Otho bringing news of defeat, he was called a liar, a coward, and a runaway by the other soldiers. To certify his words, he fell on his sword at the emperor’s feet.”

In short, the Romans honored the man who held absolutely nothing back — who put all he was as stake in everything he did and said.

Conversely, the man with nothing to lose, who risked nothing in his speech and behavior, was considered to be literally shameless (that is, unable or unwilling to be shamed). A shameless man acted without the check of honor and was thus regarded as contemptible, dangerous, and unworthy of trust. His whole being was considered a vanity; as Roman writer Petronius put it, a man who would not submit himself to test and challenge became nothing more than a “balloon on legs, a walking bladder.”

Why, the ancients, thought, should any man be taken seriously if he can act without consequence? Why should a man be listened to and followed if he has no skin in the game?

Why indeed? And yet in the modern world, we operate by the very inverse equation. Those with power and influence issue missives from a safe position far from the front. They risk little to nothing; if they are wrong, they lose little face, and continue on unashamed.

The Removal of Skin in the Game and the Outsourcing of Downside

In times past, those in power accrued both privileges and responsibilities — with greater status came greater exposure to risk. It was surely good to be king, but you also had the “Sword of Damocles†hanging over you; your decisions could bring dire consequences, and people were always gunning to take you down. Military generals, rulers, criminal bosses, and even prominent writers and scientists accepted both greater status, and with it the persistent stress, fear, and anxiety of failing and making the wrong move.

In the modern age, this dynamic has been flipped. As philosopher Nassim Taleb argues in Antifragile: “At no point in history have so many non-risk-takers, that is, those with no personal exposure, exerted so much control.â€

Bankers and hedge fund managers make risky investments and trades that contribute to cratering the economy, but avoid punishment while taxpayers pick up the tab.

Corporate CEOs run companies into the ground, but walk away with millions in bonuses.

Journalists write columns that contribute to support for a war or a criminal accusation, but retain their jobs when the claims they made turn out to be false.

Researchers publish “ground-breaking†studies that are later retracted, but do not publicly apologize or admit mistake.

Politicians and media pundits offer analyses and make predictions about current and future events that turn out to be wholly inaccurate, and yet continue to wield power and talk to the cameras night after night.

To the skin-withholders above, Taleb adds news editors who choose clicks over credibility, managers who assume minimal accountability, and paper-pushing bureaucrats of all kinds. These societal elites and cosseted desk-jockeys invert the ancient order of honor; they attain status and influence without risk, and substitute cheap talk for action. They accept the upside of their position, without being exposed to its downside — and in fact outsource that downside onto unsuspecting others. Pundits give opinions and predictions that are trusted by the general population, but suffer no consequences if they turn out to be wrong — even if actual harm befalls those who took their faulty advice. They demand a pound of flesh from others, while protecting their own skin.

Why You Should Put Your Skin in the Game

In contrast to those who keep the upside of risk-taking while foisting the downside on others, are those who continue to stake their very reputation and whole being on their words and actions. Among those with skin in the game, Taleb includes entrepreneurs, business owners, artists, citizens, writers, and laboratory and field experimenters (as opposed to scientists and researchers who work only in the realms of theory, observation, and data-mining). These are the folks who take their own risks, and keep both their own upside and their own downside.

There is also a tier above this group — those rarified few who have put not only skin, but soul in the game. These are they who take risks, accept potential harm and hardship, and invest themselves in something not only for their own sake, but on behalf of others. These are the folks who make up the heroic class. Included amongst those with soul in the game, Taleb posits, are saints, warriors, prophets, philosophers, innovators, maverick scientists, journalists who expose fraud and corruption, great writers, artists, and even some artisans who add insight and meaning to our cultural storehouse through their craftsmanship and wares. Rebels, dissidents, and revolutionaries of all kinds are also of course worthy of the title.

Why might you aspire to join the ranks of those who put their skin, and even their soul in the game? After all, aren’t those who abstain from doing so just acting in their self-interest? If you can transfer the downside of the risks you take to others, while keeping the upside for yourself, why wouldn’t you?

Here are a few reasons a man of honor should either strip or retire:

Influencing others without skin in the game is dishonorable. As Taleb succinctly puts it: “I find it profoundly unethical to talk without doing, without exposure to harm, without having one’s skin in the game, without having something at risk. You express your opinion; it can hurt others (who rely on it), yet you incur no liability. Is this fair?â€

Of course it is not fair. Would you let a friend play poker with counterfeit money while everyone else put in the real McCoy? If you were the one using fake greenbacks, and no one knew except yourself, would you feel comfortable taking your friends’ money, while risking none of your own?

That greater participation and/or power requires greater skin in the game is truly one of the fundamental tenets of human morality.

There is no growth and joy without risk and struggle. While putting one’s skin in the game is both moral and honorable, it is not an entirely altruistic endeavor. It also greatly benefits yourself — not always monetarily (though it can), but in refining your character and your manliness. Manhood is struggle — full stop. Outsourcing the risk side of your pursuits puts you in the position of spectator rather than doer. As Jay B. Nash writes in Spectatoritis, while sitting in the stands is safer, it is far less satisfying than being in the arena:

“The process of adding life to years involves a doing existence. It means facing the current. The same process brings joy to the individual as it brings richness to the group. ‘Strip or retire,’ as in the days of Greece, is still the motto. The individual who strips for action is the one who has fullness of life. The looker-on, the victim of spectatoritis, brings neither joy to himself nor heritage to his people.

Living is a struggle, competition — a hope-fear relationship. Remove that and you remove satisfaction. Competition exists not only in post, but in every zestful act. In this struggle, the relationship between the possibilities of success and the fear of failure is the balance which is the essence of interest.â€

The more you invest of yourself, the greater your chances of success. Now it’s true that those who head up huge bureaucracies — big banks and government agencies — have no problem moving up the ranks and making big bucks by keeping the upside of their endeavors for themselves, and foisting the downside on others. But for most of us — the little guys — success in our arenas is predicated on having ample skin in the game. If you’re a writer, artist, artisan, athlete, entrepreneur etc., nothing is more motivating than knowing that your success is almost entirely dependent on yourself, and that if you fail, you’re going to lose big — physically, emotionally, and financially. It’s do or die. Nobody will ever care more about your pursuit than you do, and the more you start outsourcing its risk, the less completely invested you become in the outcome.

If you watch the show Shark Tank (and you should — a lot of great lessons to be learned!) you’ll notice that Mark Cuban will often decline to invest in companies that have already received too much venture capital from other sources. There’s not enough skin in the game for him to sufficiently care about taking the business to the next level, and he knows the owner/founder likely doesn’t have enough skin in the game either. The entrepreneur usually vehemently disagrees — “I do care! I am passionate and highly motivated!†But it’s the folks with skin in the game — those with everything to lose — who are up at 3am working on their business and their art, not those with an ample safety net.

The difference ultimately comes down to ownership — you treat and invest in that which you own in a much different way than that which you rent or borrow. The satisfaction you get from taking care of that which is wholly yours is of a far different caliber as well.

Those with skin in the game are the legacy leavers. Today’s hedge fund managers, blowhard media pundits, and bozo politicians will one day be resigned to a footnote in our history books. The folks who get things done, who are remembered with reverence and respect — by books or by grandchildren — are those who lived with soul in the game. Heroes. Soldiers. Revolutionaries. Fathers. They accepted a disproportionate share of downside, in order to build a brighter upside for others. They change the world in ways both big and small — by transforming the culture, or simply changing individual lives.

Why You Should Only Trust Those With Skin in the Game

Taleb argues that our modern “absence of skin in the game†is “the largest fragilizer of society, and the greatest generator of crisis.†It is a phenomenon all the more insidious because of the complexity of our modern political and financial sectors. People on the ground can’t see the ways in which those in power are feasting on the upside of risk, while foisting its downside onto others. It’s only when something finally breaks and the vulnerable system comes crashing down, that we realize what went wrong. By that time it’s too late, and the average citizen is left holding the bag.

If one truly wishes to revive classical honor in the present age, it’s essential to make skin in the game a requirement of trust and influence. Having skin in the game doesn’t mean a man will never make mistakes, just that if he does, he accepts their downside, including personal shame. In antiquity, if someone messed up, the restoration of their status and reincorporation into society was predicated on their public contrition; there was no place for the shameless in civic and cultural life.

In modern society, we do a bang-up job of shaming folks through the power of social media, but the Twitter mob generally only gins up its mindless, insatiable outrage machine in response to inflated trivialities — off-color jokes and slips of the tongue. Yet at the same time, we leave pundits and politicians who unapologetically make false promises and predictions in their places — giving our passive blessing for them to continue behaving in ways that weaken and fragilize our world.

Lending trust and support only to those with skin in the game would not only help strengthen society as a whole, but also helps us make better decisions in our individual lives. In choosing whom to take advice from and invest emotion, time, and money in, ask yourself questions like:

Do they live their own advice and beliefs (and accept the downsides of those positions)?

Talk is cheap. It’s easy to advocate for what others should do when you don’t have any skin in the game — when you don’t have to shoulder the downside of such positions yourself.

Taleb recounts meeting a liberal tycoon who advocated for raising the tax rate on the wealthy. Yet later, Taleb found out the man kept his own fortune in off-shore accounts, shielding it from the government’s reach. Taleb compares such a “champagne socialist†to a figure like Ralph Nader, who not only stumps for liberal causes, but lives on $25,000 a year, and gives the bulk of the money he earns on his $3 million in stocks to the dozens of non-profit organizations he’s founded.

Cultural critics who advocate for a return of traditional family values, but still haven’t settled down themselves; married ministers who preach chastity while getting some sugar on the side; childless folks who offer lectures on parenting; people who vote for war, but don’t want their children to fight in it; overweight doctors that dispense advice on diets. It’s not just that these folks are hypocritical — that their beliefs don’t match their actions — it’s that they want to keep the upside of their behavior (the status of their position; the plaudits of stumping for virtue), without shouldering the downside that living their advice requires. They want others to get in the arena, while they hang out at the concession stand.

Nobody is perfect. But one should give heed only to those who admit when they mess up and truly try to practice what they preach.

What’s in their portfolio?

It’s easy for folks to take risks with other people’s money they would not take themselves. Thus, Taleb wisely advises: “Never ask anyone for their opinion, forecast, or recommendation. Just ask them what they have — or don’t have — in their portfolio.” Don’t have someone manage your money — or anything else — who puts your skin in one game, and his in another.

It’s for a similar reason that self-made billionaire Seymour Schulich advises people to buy shares in companies “where the officers and directors own a large amount of stock.†The more that employees’ own pocketbooks are tied to the fortunes of a company, the harder they’re going to work to make it a long-term success, and the better your investment will do in turn.

What would they do if they were in your shoes?

When sick patients are facing death, they often ask for every life-saving measure to be tried to prolong their lives. If they’re incapable of making that decision, families often will avail themselves of every option on their behalf, and doctors will invariably do all they can to keep the patient in the land of the living — if just barely. Yet when doctors themselves are surveyed about their own end-of-life preferences, few would choose to have life-saving interventions performed on them. Unlike patients, they know the risks, pain, and often marginal benefits that come with things like ventilation, feeding tubes, and endless rounds of chemotherapy.

What someone may recommend in the abstract — when someone else is affected — can be much different than what they would choose for themselves.

So when making a decision, ask others what they would do if they were in your exact shoes.

Do they show their face and reveal their name?

“A half-man…is not someone who does not have an opinion, just someone who does not take risks for it.” –Nassim Taleb

In antiquity, a man’s words and deeds had to be proven in the public arena. He had to address people face-to-face, so they could assess his reputation, examine his credibility, and offer challenges to his arguments.

The internet, by contrast, operates by the very opposite principle: it is highly democratic, and yet literally shameless. Writers of articles must use their real name, show their face, list their sources, and, with each thing they post, open their reputation to criticism. In contrast, blog commenters can offer an anonymous, risk-free, drive-by dissent. They are not required to present any evidence for why they should be listened to, and their bonafides cannot be vetted. Anyone can be a “former Navy SEAL†or a “medical doctor†on the web. Anyone can use sarcasm and anger to sound intelligent. And if they’re wrong, they incur no liability, no damage to their personal reputation.

I’ve long been uncomfortable with having comments on the Art of Manliness for this very reason. Yet I kept them around because I felt there were a few pros for both me and for readers; some folks really enjoy them (more clicks for me!), and people occasionally leave comments that are helpful for others (though even on a site like AoM, where the comments were a big cut above the rest of the internet, the ratio of useless to useful comments was still about 5:1). But after pondering the subject, and writing this piece, I have come to the conclusion that while it may annoy or disappoint some, and maybe even hurt my bottom line, I cannot on principle continue to host what is essentially a dishonorable medium of discourse.

So from now on, if you’d like to discuss and debate our content, please do so on Facebook, where you’ll need to use your real name, offer an opinion in front of your friends and the eyes of thousands of others, and back your words with a little more skin in the game.

Strip or retire.