Note: What you will find below is not so much a long blog post, but a short ebook; approach it as such. At over 20k words, it will probably take an hour or two to read, and surely even longer to process. This is the conclusion and culmination of this long series on manhood, and this short book really defines the concept(s) that we’ve been thinking about and working on since we started AoM back in 2008.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1: Manliness is a Choice. Choose the Hard Way.

Chapter 2: The Manhood Reserve Training Program and Exercises

Chapter 3: The Importance of Our Social Ties

Chapter 4: Virtue — The Capstones of Manhood

Conclusion

Introduction

For the last few months, we’ve embarked on a fairly epic series on the nature of manhood – its origins, historical imperatives, and standing in the modern world. Here’s a look at where we’ve been:

- Part I – Protect

- Part II – Procreate

- Part III – Provide

- Part IV – The 3 P’s of Manhood in Review

- Part V – What is the Core of Masculinity

- Part VI – Where Does Manhood Come From?

- Why Are We So Conflicted About Manhood in the Modern Age?

At this point we’ve reached the most important question of all: where do we go from here?

In my last post, I described three popular positions as to which path modern men should take, all of which I believe are ultimately dead ends.

Today I will lay out my own suggested roadmap for how to live as a man in the 21st century.

I offer this guide with the utmost humility. There is no such thing as an “expert†in manliness, and I make no absolute claims for the authoritative nature of what you’ll find below. Manhood is a big, surprisingly deep subject and my views will likely be refined as I gain further knowledge and understanding over the years to come.

At the same time, it isn’t pulled out of my rear. What you find below represents my earnest and best faith effort to distill what I have learned through six years of studying and reading about manhood and interacting with thousands of men around the world, as well as from my own personal faith, philosophy, and experience. I really believe the principles and steps below can guide a man in making the best possible life for himself.

Chapter 1: Manliness Is A Choice. Choose The Hard Way

You had no control over being born male. But becoming a man – by living the ancient code of manhood – is a choice. It has always been so.

In primitive times, the decision to follow the way of men was essentially made for you. The survival of tribes and clans depended upon all men striving to achieve the “Big Impossible†of becoming a “real man†by fulfilling the imperatives to protect, procreate, and provide. Young boys didn’t get a say as to whether or not they took part in their tribe’s violent and strenuous rites of passage, and all men were expected to hunt and to fight. A man was hypothetically able to opt-out of such endeavors, but the consequence of doing so was great shame. In a harsh environment a man could not survive alone, and so could not afford to become an outcast. Beyond a concern for physical safety, a man’s identity was so tied up with his tribe that to lose his status was emotionally crippling – a blow to his pride to be avoided at all costs. Thus our primitive ancestors were highly motivated to try to pull their own weight and meet their community’s standards of honor.

As danger receded from the perimeter, and life began to be less harsh and dangerous, the necessity of every man giving his all became less acute, and men’s leeway in choosing to live the code of manhood increased.

You may think that the decision of whether or not to strive for the traditional standards of manhood is of recent origin. But it is something men have grappled with ever since the first rays of civilization began to dawn. As life became more comfortable, men were faced with the question of how much of the old, primal ways to hold onto, and how much to cede to the emerging comforts and luxuries of settled society.

Some of the first to wrestle with how to live as men in a more domesticated landscape were the ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, who pondered and debated what constituted the good life. The Stoics argued that it could be found in fighting their society’s emerging trend towards softness and decadence and deliberately cultivating one’s ruggedness and virtue.

Many of the great Stoic philosophers happened to be extremely rich and powerful men — Seneca was the tutor and advisor to the emperor Nero, and Marcus Aurelius was emperor himself. They could have helped themselves to all the indulgences their culture had to offer. Yet despite the temptation of being surrounded by wealth and luxury, these men purposely chose to take a different path from their peers. They chose the hard way of mental and physical toughness.

The Stoics devoted much of their time and energy to developing the ability to remain calm and collected in the face of adversity, as well as cultivating an indifference to pain, fear, avarice, and social approval. They intentionally sought out the kind of challenges their peers avoided. Cold baths, strenuous exercise, wearing plain and sometimes rough clothing, eating simple fare, and even deliberately seeking out ridicule were all methods Stoic philosophers practiced and encouraged other men to adopt. They believed this was the most fulfilling way to live – the only way to grow and progress.

Fast forward to today. The amount and availability of luxuries has increased many times over. But despite the passing of 2,000 years, modern men are essentially faced with the very same decision as their ancient brethren: How much should you indulge in the ease and comfort around you, and how much should you keep yourself apart and maintain your independence, mental sharpness, and physical toughness? Should you take the path of least resistance, or the hard way?

Barring catastrophic societal collapse or another World War, there’s hardly anything in our current season of civilization that will compel men to live the ancient and universal code of manhood. If you wish to live the way of men, you will, just as the Stoics did, have to intentionally choose to buck the tide of our culture, exercise your agency, and decide to live it yourself.

Without some outside force coercing them to live the code, most modern men will follow the path of least resistance and not even try. Naturally, this has and continues to produce social problems in regards to men that governments and pundits wring their hands about.

But a few men will hear the old calls and decide to answer. Doing so in our comfortable and luxurious world requires self-will and inner-discipline. It will require you to be proactive. Instead of expending your energy complaining that today’s culture doesn’t value or encourage manliness, you will need to channel it into swimming against the tide, building yourself into a Nietzschean Superman, creating a familial tribe, and surrounding yourself with fellow men of honor.

Though the task is not easy, I’d argue that because a man who lives the code now does so of his own freewill and accord, rather than because he is compelled by an outside force, this path has never been more satisfying and fulfilling.

Join the Manhood Reserve

How do we resolve the cultural dissonance we have when it comes to manhood? Sure, we don’t really need all 21st century men to be good at being men in our current safe and luxurious environment. But what happens when things get rough and manly men are once again needed? Will we have men who have what it takes to protect and do the hard and dirty work necessary to keep things going? Can living a code of manliness actually enhance our lives and provide a deeper sense of satisfaction and fulfillment than would otherwise be possible?

During my research and writing of this series, there was an unmistakable parallel that kept popping in my head as to how to resolve and explain this conflict we have in modern society when it comes to manhood: the military reserves.

Many militaries around the world have a reserve force. It’s an organization of military personnel who aren’t full-time soldiers, but have undergone basic training and make a commitment to developing and maintaining their military skills so that they are ready to deploy should their country need them.

My proposed resolution to the conflict of modern manhood is something akin to this model of service. We’ll call it the Manhood Reserve. While abiding by the traditional code of manhood isn’t urgent in our current environment, someday it might be and we’ll need men prepared for that moment. Even if our society isn’t hit with some kind of crisis or catastrophe, our training in the Manhood Reserve will still be worthwhile. We will all encounter hard times in our own lives that require the fortitude and strength that living the traditional code of manhood develops. What’s more, living the code will allow men to both scratch the itch of their primal masculinity and achieve eudemonia — the ancient Greek ideal of a life of excellence and full flourishing.

What follows is a framework that lays out the broad principles and specific training course pursuant to an enlistment in the Manhood Reserve. It seeks to wed tradition to the realities of modernity in order to create a pathway that both reaches back and moves men forward. It is positive and proactive. Joining up is voluntary, and can be done by any man, in any circumstances, in any time. It does not require the culture around you to change or women to change. It is only dependent on you and your desire to live semper virilis – always manly.

Manhood Reserve Case Study #1: Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt was born to a wealthy family in New York City. The Roosevelts enjoyed comforts and conveniences in their 19th century brownstone that most Americans wouldn’t see until several decades later. When the Civil War tore America apart, Teddy’s father had more than enough money to pay for a substitute and thus avoid a draft into the Union Army.

If you were to judge the trajectory of TR’s life based on the first ten years of it, you’d probably guess that he’d end up as a smart and capable, but physically weak, natural history professor at some Ivy League university. Roosevelt could have easily settled into a life of cosmopolitan comfort.

But after a stern talk from his father, young Teddy chose a different path for himself.

He chose the hard way. What he called “the strenuous life.â€

In Teddy’s time, the standards of male honor largely revolved around virtues like integrity and industry – being a good man. And Roosevelt kept this code to a T. But he didn’t want to just be a good man, he wanted to be good at being a man, too.

It was a goal he actively pursued.

His adolescence was spent exercising and building up his once frail body. He took up boxing in college and became a competitive fighter. During winter breaks in school, he’d go up to Maine and hunt with the famous guide and timberman Bill Sewell. After his wife and mother died on the same night, instead of wallowing in grief and despair, Roosevelt headed out to the badlands of the Dakotas to take up cattle ranching. Despite being a four-eyed “dude†from back east, Roosevelt quickly earned the respect of rough and hard cowboys by showing he could pull his own weight and wasn’t afraid to jump into the fray: he cleared out stables himself without complaint; he captured a posse of horse thieves after tailing them for 3 days in subzero weather; he knocked out a gun-wielding loudmouth with 3 dynamite punches.

By striving to live the hard way in his younger years, Roosevelt armed himself with the fire and fight he needed to succeed in the political, social, and intellectual challenges of his later life. Even as a middle-aged U.S. president, Roosevelt didn’t let up on his dedication to testing himself and living the strenuous life; he took part in judo and boxing matches in the White House and punctuated his schedule with hunting, skinny dips in the Potomac, and brisk hikes. He stayed ever ready for whatever adventures and exploits might await him.

And what exploits they were. Roosevelt served as police commissioner, governor, assistant secretary of the navy, and president (the youngest ever to assume the office). When war broke out with Spain in Cuba, Roosevelt put together his own volunteer unit and led them in a charge up San Juan Hill. He was a devoted husband and father of six children. He read tens of thousands of books and penned 35 of his own. After his days as President were over, he set out on an expedition to explore an uncharted part of the Amazon River and nearly died in the process.

All throughout his life, Roosevelt had the choice to reject the masculine code, but he never did. He sought to ever challenge himself “in the arena†and to always “carry his own pack.â€

Some historical commentators chalk up Roosevelt’s obsession with the strenuous life to a symptom of the “male anxiety†that many 19th century urban men faced in America. It was the age of machines and steam and a man’s place in society was being questioned: What was the use of masculine strength when new machines could do the work of twenty men? With the frontier closed, what use was there for the old pioneer qualities of ruggedness and self-reliance?

Sound familiar?

Roosevelt and other men of his time ignored the hand-wringing and deliberately chose to live by the code of men even though it wasn’t demanded of them.

I think that’s why I and so many modern men admire Teddy Roosevelt. He showed that it’s possible to live in our modern world of luxury and comfort, but not be softened by it. He showed us that you could proactively choose to be good at being a man even when your surroundings or culture aren’t conducive to exercising your innate masculinity.

In short, TR showed us that it’s possible to live in civilization but not be of it.

Why Enlist in the Manhood Reserve?

Many of you are reading this and probably asking “Why?”

Why bother guiding your life by an idea of manhood that was formed in another time and is no longer suited for our modern, plush, techno-industrial world?

Why live like a man when you won’t necessarily be honored for it? When the failure to do so won’t bring shame? When it’s not required for access to women?

Some say that only a sucker would try to be his best when it isn’t required of him, when you can get ahead by simply getting by. That trying to be a man these days will simply get you taken advantage of by a system that no longer appreciates the effort.

I couldn’t disagree more.

While living the code of man might have once partly, even primarily, been about what you got from others in return, today it is something you need only do for yourself.

If you’re looking for pats on the back, turn back now.

Living the code will enormously benefit your family, your community, and your nation (even if they don’t recognize it). It will lead to friendships with other great men, and assuredly make you more attractive to women.

But it is also simply the best way to live your own life, regardless of whether or not anyone else notices or cares. How so? I submit several reasons for your consideration:

You Were Bred for It

Because of the prevalence of polygamy in early human history, it’s estimated that only perhaps 30% of men ever reproduced.

Who comprised this lucky third?

Those who landed a mate and the opportunity to have children were the men who tried to prove themselves, who dared to take risks, who ventured out and explored, who had the intelligence, strength, and courage to become successful. The men who did not take the gamble, or who did not have the prowess to be successful when they did, died childless.

What this means is that we are all descended from the strongest, fastest, smartest, bravest men of the past: history’s alpha males. Pretty heady, isn’t it? It is not a stretch to conclude that the blood of greatness runs through our veins.

What should we do with this rich, powerful heritage?

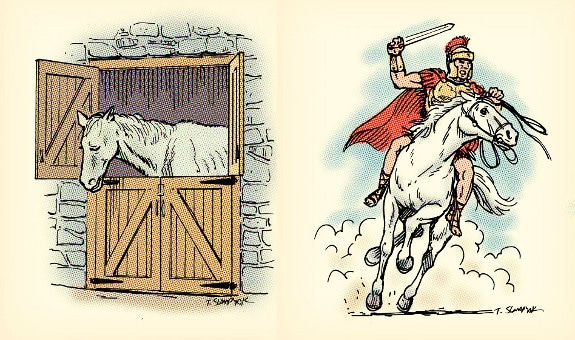

Some men squander it on a mediocre life of porn, video games, and corporate dronism. Their fiery thumos lies neglected and unused; it is as if a fine horse bred for racing was being used for pony rides at kiddie parties. Tethered to a pole, he plods in endless circles, his muscles atrophied, his eyes downcast.

Failing to exercise your primal potential results in feelings of restlessness and malaise.

By activating the switches of your ingrained masculine wiring and programming – even in small ways — all of your being comes online. Keep the flames of your thumos burning, harness the energy, and ride it hard down the rode of excellence.

You are a man. This is what you were made to do. Embrace it.

Always Ready

Men, real men who are good at being men, aren’t needed anymore in our modern world… until they are.

Who knows when the world will need men shaped and molded by the ancient ideal of manliness? Sure, life is for the most part comfortable and pleasant now and we really don’t need every man to be un vero uomo, but it’s hubristic and shortsighted to believe that it will always stay this way. Maybe the doomsayers and zombie apocalypse fans will be right and some natural or human upheaval will shake society so violently that we resort to a Hobbesian state of nature with marauding gangs wandering the grey landscape just like in The Road. I don’t know about you, but I want to know I could hack it in that sort of situation. I want to be able to look my wife and kids in the eye and say: “I’ll protect you and take care of you,†and mean it. I’d also want to surround myself with other good men, who were also good at being men — brothers with whom I could, as Cormac McCarthy puts it, “carry the fire†as we set out to re-build the world together.

But isn’t it silly though to spend one’s life preparing for a contingency that may never come to pass?

It would be if this way of life wasn’t simultaneously the most fulfilling.

Even if society never unravels or blows up, the man who spends a lifetime cultivating the traits inherent to the code will have the confidence, resourcefulness, and mental fortitude to be ready for whatever comes. If his life never intersects with a great crisis, he’ll have the capacity to handle the smaller emergencies in his day-to-day life – from an unexpected death in the family to a tornado razing his house.

He’ll also experience the satisfaction of keeping his body in peak condition and learning the kinds of skills that will allow him to handle any situation. There’s no need to over-analyze it: knowing survival and tactical skills is just plain cool and few things feel as good as being fit and strong.

“Field equipment is a most excellent hobby to amuse one during the shut-in season. I know nothing else that so restores the buoyant optimism of youth as overhauling one’s kit and planning trips for the next vacation. Solomon himself knew the heart of man no better than that fine old sportsman who said to me ‘It isn’t the fellow who’s catching lots of fish and shooting plenty of game that’s having the good time: it’s the chap who’s getting ready to do it.’†–Horace Kephart, Camping and Woodcraft, 1918

Finally, there’s great satisfaction to be found merely in getting ready for something – anticipating it and preparing for it. How many of us have found that the anticipation of Christmas or a vacation is more enjoyable than the occasion itself! Learning new skills, practicing for various scenarios, trying out different equipment is all quite enjoyable. Such preparation also keeps your body strong and your mind sharp.

Manhood Reserve Case Study #2: Dwight D. Eisenhower

When Dwight D. Eisenhower joined the military, he had a great desire to serve his country and to lead men into battle. But after graduating from West Point in 1915, he was given assignments which revolved around training troops and coaching the Army football team.

When World War I started, Ike saw his opportunity to finally see action and was eager to get right into the field. He applied several times for overseas duty, but his requests were denied. Instead, his skill in organization was put to use in preparing regiments to go “over there.â€

Ike fell into a general gloominess. But though he felt his talent was being wasted, he continued to contribute as much as he could, in whatever capacity he could, to the war effort.

In 1918, Eisenhower’s dedication appeared to finally pay off. He was given the opportunity to command a troop in Europe, and he began preparing for every exigency… except one: the surrender of the Germans.

Eisenhower was crestfallen. “I was mad, disappointed, and resented the fact that the war had passed me by,†he recalled. It was said that this was the “war to end all wars†and Ike felt he had “missed the boat†and would never get the chance to test his mettle in battle. He considered leaving the military and entering civilian life, but decided to stay in. For while he hadn’t gotten into the field, his military career was not without his consolations, as it brought him into contact “with men of ability, honor, and a sense of high dedication to their country.â€

And so Eisenhower continued on in the military, doing his best and serving with honor in whatever assignment he was given. Even when given administrative desk jobs, he acted well his part. Though his job didn’t require it, and though he thought he would probably never need it, he continued to study military tactics and strategy, for it kept him physically and mentally sharp and he simply enjoyed it.

And then 30 years – 30 years! — after his career in the military had begun, Eisenhower had his date with destiny.

In 1942, Ike found himself a major general and in command of the European Theater of Operations in WWII. He’d go on to lead the largest amphibious invasion in the history of the world. Because Eisenhower always strived to do his best and remain ever ready to serve in a crisis, he was prepared to rise to the challenge and performed splendidly.

Like Eisenhower, many modern men feel “gloomy†that they’ll never have the chance to test their mettle, to prove that they are really men. But instead of giving up, we should be like Ike by remaining ever ready to answer the call of: “Give us men!â€

The Path to Eudemonia

Besides readying yourself for that unforeseen time when men who are good at being men are once again necessary, there’s just something invigorating, exciting, and — dare I say? — romantic about living by the traditional code of manhood. Striving to live by the code of man and taking the hard way just makes life more satisfying — at least it has for me.

Traveling the hard way involves delayed gratification and earning one’s rewards, which makes them all the sweeter once we do partake. And sacrifice and discipline constitute the only route to creating value in the world and leaving a legacy – the only path to true happiness.

The ancient Greek story of “The Choice of Hercules†illuminates well these profound truths. According to the ancient Greek historian Xenophon, Socrates cited this tale while making a case against indolence and in favor of the hard way. The story remained popular throughout the eighteenth century; John Adams used it to guide his life and even wished to make an illustration of the tale the design for the Great Seal of the new nation.

In the story, a young Hercules is very perplexed as to “what course of life he ought to pursue.†He goes out into the wilderness to ponder the question, and is there approached by two goddesses, one symbolizing Pleasure and the other Virtue. Each seeks to convince the young man as to why he should choose to pursue their respective paths.

The goddess of Pleasure goes first, and promises Hercules that he will find happiness in a carefree life of luxury and ease – one in which he can gratify all of his desires, whenever he wishes.

Then the goddess of Virtue steps forward and makes her case:

“Hercules, I offer myself to you, because I know you are descended from the gods, and give proofs of that descent by your love to virtue, and application to the studies proper for your age. This makes me hope you will gain, both for yourself and me, an immortal reputation. But, before I invite you into my society and friendship, I will be open and sincere with you, and must lay down this, as an established truth, that there is nothing truly valuable which can be purchased without pains and labor. The gods have set a price upon every real and noble pleasure. If you would gain the favor of the Deity, you must be at the pains of worshiping him: if the friendship of good men, you must study to oblige them: if you would be honored by your country, you must take care to serve it. In short, if you would be eminent in war or peace, you must become master of all the qualifications that can make you so. These are the only terms and conditions upon which I can propose happiness.”

The goddess of Pleasure here broke in upon her discourse: “You see,†said she, “Hercules, by her own confession, the way to her pleasures is long and difficult; whereas, that which I propose is short and easy.â€

“Alas!†said the other lady, whose visage glowed with passion, made up of scorn and pity, “what are the pleasures you propose? To eat before you are hungry, drink before you are athirst, sleep before you are tired; to gratify your appetites before they are raised. You never heard the most delicious music, which is the praise of one’s own self; nor saw the most beautiful object, which is the work of one’s own hands. Your votaries pass away their youth in a dream of mistaken pleasures, while they are hoarding up anguish, torment, and remorse, for old age.â€

“As for me, I am the friend of gods and of good men, an agreeable companion to the artisan, a household guardian to the fathers of families, a patron and protector of servants, an associate in all true and generous friendships. The banquets of my votaries are never costly, but always delicious; for none eat and drink at them, who are not invited by hunger and thirst. Their slumbers are sound, and their wakings cheerful. My young men have the pleasure of hearing themselves praised by those who are in years; and those who are in years, of being honored by those who are young. In a word, my followers are favored by the gods, beloved by their acquaintances, esteemed by their country, and after the close of their labors, honored by posterity.â€

Hercules, of course, chooses the way of virtue – the hard way – the path to real pleasure, true happiness, and immortality.

It’s important to remember too that the code of manhood isn’t simply about what we sacrifice and strip out of our lives in the pursuit of excellence. It’s also about adding the good things – creative work, strong, close relationships, mastery of knowledge and skills. All things modern researchers have told us are the keys to a satisfying, happy life.

In short, living the code of man pushes us to be our best, to use all our potentialities, and so to achieve eudemonia – full flourishing.

The Overarching Principles of the Manhood Reserve

So you’ve decided to enlist in the Manhood Reserve. Congratulations! By choosing the hard way, you have decided to place yourself among the elite of men.

As you pursue this course of life, you will need to seek to incorporate specific elements of the code of manhood into your life. As you do so, you should guide your actions and decisions by a set of overarching principles. Let us here discuss the latter, and devote the next chapter to laying out the former.

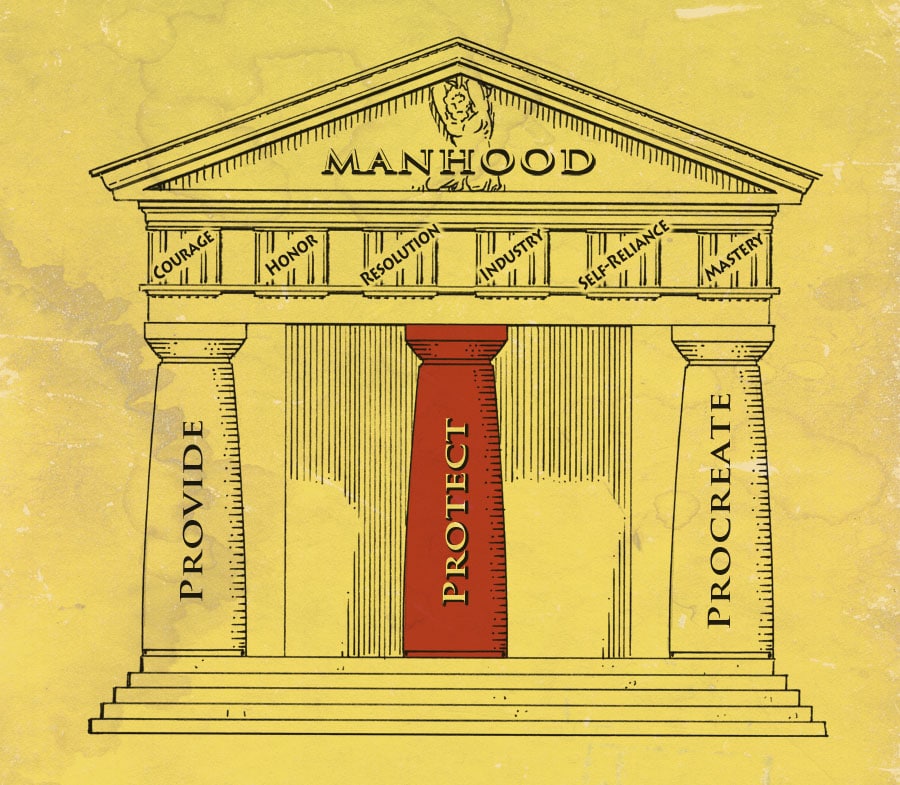

Find a Balance Among the Three P’s

As you think about crafting your own roadmap to manhood in the 21st century, keep in mind the Three P’s of Manhood: Protect, Procreate, and Provide. Remember that each of the pillars is important and each interacts and relates with the other. It may be tempting to focus on the pillar of manhood that appeals to you the most or is simply the easiest to achieve, but you do so at your own peril. As we’ve noted throughout the series, when one or two of the P’s of Manhood are weakened or non-existent, greater stress is placed on the remaining pillar(s), causing them to twist and contort.

Becoming what the ancients called a “Complete Man†requires developing each pillar to your fullest capacity and in balance with one another. Building all three pillars of your manhood awakens all the dimensions of primal masculinity, ensures that all of your human potentialities are exercised, and leads to a life of eudemonia.

Neglect Not the Protector Pillar

As you seek to balance the 3 P’s in your life, you must make a special effort not to neglect the Protector pillar.

Much of this roadmap applies equally well to females who are seeking to live a good life, and there are certainly women who are drawn to traveling the hard way. There is a good deal of overlap, particularly in the Provide and Procreate pillars, that men and women alike should pursue.

Thus, as we argued previously, the imperative of the 3 P’s that is most distinctly masculine and represents the core of manhood is the Protector role. It is this imperative that most calls upon men’s unique biological and psychological attributes. Men are (generally) stronger than women, more expendable, and have a tendency for risk-taking, exploration, and dominance. The way we think is geared towards systemizing and strategizing, which is vital for success in violent skirmishes, and even a man’s desire for male camaraderie and status can be traced back to our evolved role as warriors.

For this reason, the Protector role really acts as the cornerstone of the edifice of manhood. The twisting and contorting of the pillars mentioned above is most apt to happen when it is weakened or missing in the lives of men.

We see that today in the United States. With only .5% of citizens serving in the military, fulfilling the Protector role is more abstraction than reality for most men. Far too much of the weight of manhood has shifted to the Procreation pillar, and sex has become the primary source of a manly identity for many young men. Instead of playing a part in a healthy, well-rounded life, we have a society of young men who devote all their time and energy to becoming master pick-up artists or who stare dead-eyed all day at online porn.

Our wise ancestors foresaw this inevitability, and sought to strengthen the Protector pillar in order to strengthen manhood, and society as a whole. As I’ve read the works of history’s greatest minds on what it means to be a man, there’s always an emphasis on maintaining the attributes of the warrior. These statesmen and philosophers understood that martial qualities carry over and make possible the other roles of manhood (you can’t procreate or provide if you’re dead), and also stave off cultural decadence; the adoption of the hard, tactical virtues not only prepares men to serve in times of war, but counteracts the emasculating pull of luxury and comfort in periods of peace.

For example, Socrates and Aristotle argued that a strong body made a strong mind and that courage on the battlefield or in the wrestling ring translated to courage in the intellectual and moral arenas. Renaissance and Enlightenment philosophers such as Montaigne, Rousseau, and the Founding Fathers urged men to beware of effeminate-inducing luxury by taking part in vigorous bodily exercise, living Spartanly, and being well-versed in martial skills.

All of this is to say that to truly live the code of man in our modern world, an emphasis on the Protector or warrior role is required.

I’ll admit that this conclusion surprised even me. I’ve never been one to equate manhood with physical strength and martial courage, but after years of reading, writing, and thinking about the subject of manhood, it’s hard for me to deny the Protector pillar’s importance in a robust and complete idea of manliness. I sincerely believe that this dimension of masculinity is what modern men lack most acutely in their lives. At least, I know it’s lacking in mine and from my own experience, focusing on developing the traits of the Protector role has made me better and more capable in my other roles as a man. It’s also given me a renewed energy as well as intellectual, philosophical, and spiritual vigor. The fire and fight of the Protector pillar carries over to the pursuits and battles of the soul.

Activating the energy of the Protector pillar isn’t easy in our peaceful world (unless of course you’re a soldier, firefighter, etc.). But it is doable: as you’ll see in my specific steps on living the code of man, most of them emphasize attributes related to the way of the warrior.

Emphasize the Concrete Over the Abstract

“Man’s kinship with the gods is over. Our Promethean moment was a moment only, and in the wreckage of its aftermath a world far humbler, far less grand and self-assured, begins to emerge. Civilization will either destroy itself, and us with it, or alter its present mode of functioning. And culture…will of course continue but likewise change. The realm of ideas and symbols will have to be lived closer to the bone.” — Terrence Des Pres

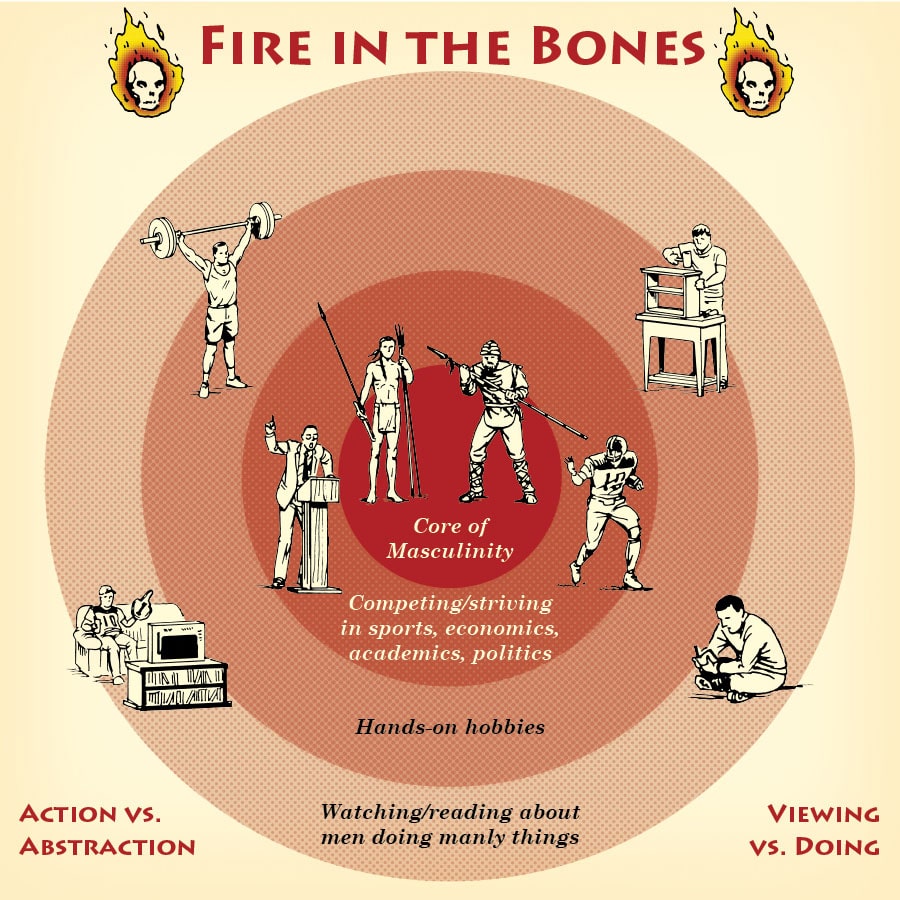

Another thing to keep in mind as you chart your own roadmap to manhood in the 21st century: most aspects of the traditional code of men have become abstractions in our modern world — particularly as they relate to the Protector role.

At the very core of the ancient code of manhood is hunting and fighting. These were/are the most distinctly masculine of imperatives and the main channels through which men competed for dominance and sought to prove their prowess and status. But they are also, of course, no longer activities most men participate in on a regular basis.

Instead, men spend their time engaging in abstractions of these traditionally manly pursuits. In the first layer out from the core, men “battle†for dominance in the arenas of sports, politics, and business. Such competitions, though they do not require the level of fire and fight of true battle, can still be quite fulfilling. So too can hands-on hobbies that challenge our minds and bodies and lead to the pursuit of mastery.

“The machine age has, of course, already supplied an unexampled wealth of leisure and what happens? The average man who has time on his hands turns out to be a spectator, a watcher of somebody else, merely because that is the easiest thing. He becomes a victim of spectatoritis—a blanket description to cover all kinds of passive amusement, an entering into the handiest activity merely to escape boredom. Instead of expressing, he is willing to sit back and have his leisure time pursuits slapped on to him like mustard plasters—external, temporary, and, in the end, “dust in the mouth.â€

Granted freedom, many men go to sleep—physically and mentally, organically and cortically. Not having the drive for creative arts they turn to pre-digested pastimes, prepared in little packages at a dollar per. This has literally thrown us into the gladiatorial stage of Rome in which the number of participants becomes fewer and the size of the grandstands, larger. Spectatoritis has become almost synonymous with Americanism and the end is not yet. The stages will get smaller and the rows of seats will mount higher.†–Jay B. Nash, Spectatoritis, 1938

This satisfaction decreases as a man moves further away from the core of manhood, and starts dealing in abstractions of abstractions. Instead of playing a sport, men will watch other men play sports on TV or play the sport on a video game. Instead of setting off on their own adventures, they browse through the adventures of others on their Instagram feed.

The abstractions of manhood don’t just occur in the Protector role, either. You can see it in the Procreator role when instead of having actual sex with real, live women, men watch other men have sex with women on their computer. In terms of the Provider role, some men endlessly read about starting successful businesses, but never pull the trigger and actually start their own.

In short, modern men too often fall victim to the plague of spectatoritis.

This isn’t to say you shouldn’t spend any time in abstractions of masculinity. Abstractions of hunting and fighting have always been a part of men’s lives – even when they spent their time actually hunting and fighting! Even primitive tribes had sports and good-natured brawls and sat around the fire listening to storytellers spin the tales of the manly deeds performed by their ancestors.

Sports and hobbies and creative work are all highly enjoyable pursuits that contribute to your becoming a well-rounded man. And pondering, studying, and even watching other men do manly things can lend our lives needed direction, guidance, and inspiration. It’s all about balance, and spending more of our time in the heat of the arena, and less of our time in the cold and gray of the grandstands.

If you really want to experience the ancient code of manhood at its most concrete, primal core, hunt, fight, and procreate. If you can’t do that, do activities that are close stand-ins. Instead of spending all day Saturday watching other men play basketball, get a group of guys together for a pick-up game. Instead of watching UFC, join an MMA gym. Instead of masturbating to porn, have sex with your wife. You get the idea.

Just Flip the Switch

Too often manliness is presented as an all or nothing proposition: either we must give up on living the code of manhood altogether or return to primitive times when “men were men.†For those in the latter camp, true masculine fulfillment isn’t possible unless we’re living right in the core of things — hunting and fighting for our lives. Anything else is just empty pretend play that cannot ultimately satisfy.

For most men, neither proposition is desirable (or practical), and they thus find themselves stuck between what seems like a rock and a hard place: they cannot fully access the old ways nor completely embrace the new ways, and so they decide to do nothing at all. They end up drifting along and feeling a deep sense of malaise that’s difficult to shake.

I strongly reject this all or nothing proposition. You don’t have to become a sensitive ponytail guy or a Neanderthal.

It is possible to wed the best of tradition with the best of modernity.

As we argued in our series on the 5 Switches of Manliness, it’s not necessary to abandon all the comforts and progress of the modern age and return to a complete state of nature in order to experience full masculine and human fulfillment. Instead, think of your primordial male characteristics as power switches that are either on or off.

While we often think that throwing those switches requires arduous, perfectly “authentic†tasks, they can in fact be activated by surprisingly small and simple means. Just because you cannot live exactly like your manly ancestors, does not mean you cannot do something.

Take the parts of masculinity that have been an integral part of manliness for thousands of years and try to have some semblance of them going on in your life. Not to the extent that they were manifested in primitive times, but present nonetheless. So you can’t live in a cave – go camping regularly. So you aren’t hoisting heavy rocks on a daily basis – lift weights. So you aren’t running down a Mastodon with your bros – hang-out often with an all-male group of friends. You’ll be surprised how “basic†changes in your lifestyle will increase your virility and feelings of fulfillment.

If you’re familiar with the paleo or ancestral health movement, this approach towards manhood is very similar. Contrary to popular belief, paleo adherents don’t advocate for living just like cavemen. Rather, they argue that in order to build the strongest and healthiest body, we should eat a diet and take part in activities similar to our ancestors because that’s what our genes were evolved for. So instead of eating a modern “balanced†diet, paleo practitioners eat fewer processed carbs and higher amounts of protein and fat — a diet similar to our tribal forebearers. This doesn’t mean paleo folk are out killing their own bison with a spear; most just buy beef at their local organic food stores. Paleoists look to the past for the spirit, not the letter of the law. We should do likewise with manliness.

So don’t get hung up on the idea that to live the code of men you have to go out into the wild and build your own cabin – though, you certainly can. Use the traditional code of manhood as a framework, modify it to fit our modern landscape, and simply flip the switch.

Chapter 2: The Manhood Reserve Training Program and Exercises

When men do terrible things in our modern society – wreck the economy, thwart political compromise, commit violent crime – their masculinity is to blame.

Yet when men do great things – make technological and scientific breakthroughs, jump from space, kill terrorists — their masculinity is seen as irrelevant to the accomplishment.

In truth, both of these are sides of the very same coin: masculinity is simply raw energy. Energy cannot be created nor destroyed and can be used for either good or ill.

Societies around the world for thousands of years understood this truth, and wisely constructed outlets to exercise and channel masculine energy towards the collective good.

Today, such built-in outlets have largely vanished from the landscape. Competition, recess, and physical education have been stripped from schools; military service is not compulsory; strength-requiring labor, both in the workforce and at home, is no longer necessary; fighting over honor, outside a gym or ring, will get you hauled into court.

Just as with all aspects of the traditional code of manhood, if you want to exercise your innate masculine energy, you’re going to have to purposefully and proactively find ways to do it yourself.

Below I outline the elements that should be part of the training program of every recruit to the Manhood Reserve. Each is essential in flipping the switches of your innate masculine energy. So far we’ve talked in more general terms – now I want to get more specific. For each element, I have suggested some concrete ways to incorporate it into your life. But exactly how you go about activating the elements is really up to you. The most important thing is to read this and do something – to take action on it.

Note: What I offer here is a framework. In writing this chapter, I quickly discovered that to give each element a complete treatment would turn this short book into a huge one. So I’ve described the essentials of each element relatively briefly, and then pointed to further articles of ours on the subject for those interested in learning more.

1. Increase Your Testosterone

Testosterone is the fuel that will power you along the road to manhood. It’s what makes men strong, daring, and aggressive. If you want to get the most out of the suggestions below, you’ll do well by topping off your testosterone tank before you start out.

Action Steps:

- Read our thorough Testosterone Series and follow the suggestions outlined in the post on how to naturally increase your T.

Further Reading:

- The Declining Virility of Men and the Importance of T

- The Benefits of Optimal Testosterone

- A Short Primer on How T is Made

- What’s a “Normal†Testosterone Level and How to Measure Your T

- How I Doubled My Testosterone Levels Naturally and You Can Too

2. Build Your Physical Strength

It’s easy to dismiss strength-building as brutish – something “bros†are concerned about but not “real men.â€

I know when I first started the Art of Manliness, I didn’t put too much stock in physical strength as an important component of manhood. Strength of character, sure, but physical strength was more of a secondary pursuit. Maybe it was because I started AoM partly to get away from the overdone fetishization of getting ripped that was (and is) promoted by other men’s magazines. Maybe it was because I wasn’t in shape myself at the time. (As I’ve mentioned in this series, we often construct our definition of manhood in accordance with that which describes ourselves best, and I’m certainly not immune to this temptation!)

Yet over the years, as I’ve studied masculinity more and starting building my own body, my attitude towards the importance of physical strength has changed. I’ve come to see it as a defining characteristic of manhood.

Physical strength constitutes one of the few and most significant differences between men and women. If the Protector role represents the core of masculinity, then physical strength forms its very nucleus. It’s the fundamental factor as to whether a man can hold his own in a fight – whether he can push back when pushed. It’s thus central in how humans viscerally judge a man’s manliness. You can call it stupid or silly or archaic, but it all goes back to the way we evaluate men — could they keep the perimeter in a crisis? Though we now live in a comfortable time of peace, that hasn’t changed the fact that men and women alike (even the most progressive of them) find men who appear physically strong and fit more respectable, authoritative, and attractive than men who aren’t. Thus, if you want to feel more like a man (and be treated like one), seek to build your body.

Granted, strength isn’t much needed in today’s world where men sit behind desks at work all day. But being strong is never a disadvantage. Even in our safe environment, strength still comes in handy. I want to know that I’m strong enough to save my own life or the life of others; I want the strength to lift heavy bags of cement or mulch when I’m working around my house; I want to be strong enough to put an attacker to the ground.

As I’ll argue below, strength of character and virtue is vital to manhood. But are you prepared to fight for your principles? Likewise, can you truly say you’re a “good family man†if you could easily be outmuscled by a bad guy trying to get at your wife and kids? Strength and virtue are not mutually exclusive pursuits; strength is what secures our virtue onto us.

Beyond the idea of building strength for its own sake, and for its practical benefits, I think there’s a case to be made for doing so in order to fortify the mental, moral, and spiritual aspects of your life. Just as we sometimes set up a false dichotomy between virtue and strength, so do we too often present brains and brawn as mutually exclusive. Many great men in history, including philosophers and men who made their living with their minds, rejected this phony divide, and emphasized the importance of building bodily strength and mental strength. Physical strength boosts one’s mental determination, and mental strength increases physical fortitude. We would do well to follow the ancients’ goal of achieving mens sana in corpore sano: a sound mind in a sound body.

Finally, besides the practical and spiritual benefits that accrue to the physically strong, it just feels awesome knowing you can hoist a lot of weight off the ground. The first time I deadlifted 450 lbs and saw the bar bending in the mirror, I felt like a beast. I let out a primal shout of achievement and carried that feeling with me the rest of the week.

Not every man has the physiological make-up to get huge and ripped. But every man can become stronger, than he is now. Whatever your other interests, no matter your build, if you want to feel your most virile, get acquainted with the iron.

Action Steps:

- Start a strength training program. The program I have long recommended for beginners and used myself is StrongLifts 5X5. More recently I have had great success with making gains by using the Critical Bench Program.

- Purposefully incorporate more physical activity into your day-to-day life – use a reel mower instead of a gas-powered one, chop your own wood, etc.

Further Reading:

- AoM’s Fitness Section

- The 5 Switches of Manliness: Physicality

- How to Establish an Exercise Routine

- Why Every Man Should Be Strong

3. Develop Your Physical Toughness

“Soft lands tend to breed soft men.†– King Cyrus the Great

If you’re already strong, the next question is, are you tough?

Even though we often conflate these attributes, they’re two different things.

Khaled Allen defines toughness as “the ability to perform well regardless of circumstances.†It’s being able to handle adversity without breaking down and surmounting obstacles instead of turning back. It’s about having an indomitable will, being a man who’s able to take a hit and come back for more — a scrapper who’s “game†no matter the odds. If you want to travel the hard way, you’ve got to be hard!

We certainly admire toughness in women (as did primitive cultures around the world). But, a greater degree of mental and physical toughness is expected from men. Even if it is no longer demanded of them.

We live in a society where you practically never have to spend a single minute of your life uncomfortable. Our day is spent going from a climate-controlled house, to a climate-controlled car, to a climate-controlled office and back again. Ample, calorically dense food is never more than a few feet away. We can go an entire week without a piece of our shod and clothed skin touching a patch of dirt or brushing against a plant. Opportunities to develop your toughness are thus something you’ll have to intentionally create for yourself. (Are you seeing a common theme here?)

Toughness is a skill that can be honed like any other, and can be broken down into two aspects: physical and mental. The two are intertwined and feed each other, but let’s tackle each in turn, beginning with physical toughness.

Allen argues that “being physically tough is very different from being strong, fast, or powerful. Physical toughness includes the ability to take abuse and keep functioning, to recover quickly, to adapt to difficult terrain and contexts, and to tolerate adverse conditions without flagging.â€

It’s awesome to be able to deadlift 3X your weight, but can you lift a giant, uneven rock? It’s great to be able to do pull-ups on a bar, but could you pull yourself onto a tree branch? You can run on a treadmill, no problem. How would you do running up a rocky, root-strewn hill? Everybody can take a hot shower – can you turn the knob all the way to cold without screaming like a little girl? How far could you backpack in a single day before crying uncle?

Work to develop your physical toughness by increasing your strength in a wide variety of environments and boosting your tolerance to pain and discomfort.

Actions Steps:

- Get out of the gym and exercise outside in a variety of environments.

- Increase your temperature tolerance by working out on a hot day or venturing out on a cold one scantily clad (always use wisdom in discerning your limits – you want to push yourself, not hurt yourself).

- Take cold showers.

- Increase your mobility and flexibility.

- Thicken the skin of your feet by running barefoot.

- Exercise with your nasal passageways constricted.

- Develop your endurance and ability to “ruck†over long distances.

- Do a GoRuck challenge.

Further Reading:

4. Develop Your Mental/Emotional Toughness

Mentally tough men are able to stay calm, cool, and collected when things in their life – big and small — go awry. They don’t lose their temper or fall to pieces when faced with stress. Instead, they’re able to maintain perspective on the problem and concentrate on how to solve it (or simply ignore it for the insignificant annoyance that it is). They follow the wise way of the Stoics.

This aspect of the code of manhood has long been a target for feminists and cultural critics, who argue that suppressing the open expression of feelings stunts men’s emotional life and leads to psychological and social problems.

I think this proposition comes from a well-intentioned place, but is ultimately misguided. What these social critics and talking heads fail to understand is that it’s not “manhood†that’s the problem, but an incomplete, utterly impoverished modern idea of manhood that’s at issue. The only thing young men today know about the injunction to “Be a man!†is that it represents some kind of hazy standard of tough guy machismo. We have not taught them the rich nuances that were part of the code for thousands of years. Our manly ancient forbearers understood that it’s quite possible to be stoic and cultivate a rich emotional life; the two aren’t mutually exclusive. Even Victorian men, famous for their advocacy of the “stiff upper lip,†weren’t shy about crying over sad poetry, writing highly sentimental letters to friends and lovers, and showing their male buddies a level of physical affection that would make us moderns uncomfortable. True manly Stoicism is not about suppressing one’s feelings entirely; it’s rather a matter of knowing when to turn on the toughness and when to turn it off. You don’t live like a rock every day, you just have access to that firm, steady energy, should you need it.

Thus the solution to men’s supposed emotional problems is not to chuck the code of manhood, but to double down on it! To actually teach it in its fullness.

The highly sensitive man is something people like the idea of in the abstract, but recoil from when encountered in the flesh. People, whether they can admit it or not, want to know they can depend on men when things get hard; even in our “enlightened†culture, they still inwardly cringe at a man who falls to pieces in the face of frustration or adversity. In the midst of a familial crisis, women want their fathers and husbands to stand strong and be able to take action. While we don’t face many physical dangers today, when they do happen, it’s almost invariably left to the men to handle.

While social commentators posit that deep down, men are crying out to, well, cry, I simply haven’t found that the majority of men fervently desire the freedom to disgorge their feelings at the drop of a hat. On the contrary, I think most men very much like to feel a little emotionally tough – it gives them a sense of pride and confidence – a satisfaction equal to, if not superior to, that of being able to tear up without shame during an episode of Grey’s Anatomy.

Developing mental and emotional toughness offers other personal rewards as well. Big goals and the good things in life require hard work, sacrifice, and willpower. Mental resiliency helps us handle the little setbacks and daily annoyances that might otherwise get under our skin and disrupt our happiness and progress.

Mental and emotional toughness can be increased by taking the steps towards physical toughness outlined above. Purposefully creating small discomforts, inconveniences, and tests of willpower for yourself will strengthen it as well. Anything that builds up your powers of discipline and delayed gratification are a boon to all-around toughness. Also learn and practice ways to lower your physiological response to stress and threats.

Action Steps:

- Fast at least once a month for 24 hours.

- Try writing with your non-dominant hand.

- Close and put down a book when it’s getting very exciting and you want to keep going.

- Learn how to manage your day-to-day stress.

- Familiarize yourself with the warrior color code and learn how to manage stress from more serious threats.

- Know how to use tactical breathing to calm yourself.

- Meditate daily.

- Use biofeedback apps to boost your resiliency and take control of your physiological response to stress.

- Do exercises to strengthen your willpower.

- Do exercises to increase your attention span.

- Read a long book or article all the way through without stopping to surf around to other things.

- Keep a strict diet 6 days a week. Make the 7th day a free day where you eat whatever you like.

- Know your purpose and plan in life — as Nietzsche put it, “If you know the why, you can live any how.”

- Understand the way your brain and body lie to you about how much push you actually have left when you think you can’t physically or emotionally go on — talk to yourself about this when you’re tempted to give up.

Further Reading:

- Being the Rock

- Building Your Resilience Series

- Be Clutch, Don’t Choke: How to Thrive in High Pressure Situations

- The Power and Pleasure of Delayed Gratification

- Discipline: The Means to an End

- Willpower: The Force of Greatness

- The Kingship of Self-Control

- The Majesty of Calmness

5. Learn to Fight

“In this world, strength of a certain kind–matched of course with intelligence and tirelessly developed skills–determines masculinity. Just as the boxer is his body, a man’s masculinity is his use of his body. But it is also his triumph over another’s use of his body. The Opponent is always male, the Opponent is the rival for one’s own masculinity, most fully and combatively realized….Men fighting men to determine worth (i.e., masculinity) excludes women as completely as the female experience of childbirth excludes men.†-Joyce Carol Oates

Fighting and violence are at the very core of masculinity. Researchers theorize that nearly every part of uniquely male physiology — from our shoulders, to our height, to our faces and hands — evolved expressly for the purpose of man-to-man combat. Yet few male propensities have been as maligned.

“We don’t want people to get hurt,†we say. “Male violence oppresses others.†“Violence is only for the weak.â€

Just like masculinity as a whole, violence itself is thought to be the problem, rather than how violence is used.

When we think about male violence, we think about rape and domestic battery. We don’t think about all the violence that’s done on our behalf so we can live our safe, comfortable existence where we never have to see two men grapple for their lives. The outsourcing and distancing of ourselves from violence has led to the naive belief that it is possible and desirable to try to breed this trait out of men altogether.

Instead of teaching young men: “You’ve got an amazing power and energy inside of you – a force that drove the Vikings and the Spartans and the Minutemen and the GIs,†we teach them: “You have something wrong with you, a dark, bad drive that hurts people. Deny it. Smother it. Exclaim that you’re not like other men and reject it altogether!â€

Nobody likes violence until they’re sitting on a plane that’s been hijacked by terrorists and it’s the men who hatch a plan to take it back and kill them. Nobody likes violence until someone breaks into their house, and a man gets up to confront the intruder. Nobody likes violence until their freedom is at stake and they need men to storm the beaches of Normandy and run a knife through the enemy’s kidneys.

As a society we have this willfully self-deluded hope that we can smother men’s violent tendencies altogether because in our current society we don’t need men who can physically fight; and if we ever do, we’ll just cross our fingers that they’ll be able to instantly turn it back on again.

Far better would it be if we acknowledged the innate energy of violence in men, and both reverenced its potential and cautioned against its misuse — encouraging its principled cultivation and teaching that it should be channeled towards good, moral ends – to protect the weaker, uphold our principles, and guard our way of life.

While it is often thought that encouraging men to take part in structured, controlled violence will lead to a more violent world, the research indicates otherwise. For example, when police officers are trained in a martial art, their use of firearms and other weapons goes down. As philosopher Gordon Marino argues, men “who do not feel easily threatened are generally less threatening.â€

In my experience, those who have actual experience with violence – even simply within the controlled confines of a boxing ring – are most likely to say it should only be employed when absolutely necessary. They intimately understand the unromanticized reality of violence. They have been humbled by it. It is men who have only experienced violence vicariously through stylized video games and movies that are prone to unleash it in a destructive, narcissistic manner.

You need not wait for society to see the wisdom in this (I wouldn’t hold your breath). The individual man has plenty of reason to cultivate his fighting spirit on his own.

Besides its necessity in being able to protect others, physical fighting can help you withstand the mental and emotional blows that every man will experience in his life.

“How much can you know about yourself if you’ve never been in a fight?” asks Tyler Durden, the protagonist in Fight Club. When you get in a physical fight and take that first punch in the nose and find yourself on the mat, it’s in that moment you learn if you’re the kind of man who gets back up after he’s been knocked down. By giving and receiving physical kicks and punches you learn that pain is temporary and physical wounds heal. This knowledge bolsters your confidence outside the ring as well, endowing you with mental and emotional resilience, as well as moral fortitude.

Us moderns have a hard time accepting this idea and reconciling martial and moral virtues. We like to keep the two in separate mental compartments or act like they’re fundamentally different. The ancients didn’t see it that way – they understood that moral courage and physical courage were of the same essence, and that testing one’s physical courage on the battlefield or in the sporting arena would in fact bolster their moral courage faster than a hundred “risky†intellectual or philosophical decisions. It’s telling that Aristotle compared developing the philosophical mind to the boxer developing his physique and that the Stoics would often refer to soldiers and wrestlers as ideals to follow.

Christian churches at the turn of the 20th century understood this connection between physical and moral courage as well. This was another time in our history where the role of men and masculinity was being questioned. Many churches created their own boxing gyms and leagues, rightly sensing that building up their young men’s virility in the ring would help them be all-around better men – able to live their faith more muscularly.

I find it interesting, too, that many of our greatest writers and minds were also fighters and credited their study of martial skills to their success. Aristotle’s famous Lyceum also included a wrestling school; students grappled not only with ideas, but with each other. Ernest Hemingway boxed religiously, as did Jack London. Many modern philosophers, such as Marion, are students of the sweet science as well.

Vivere militare est — to live is to fight.

Are you prepared to live?

Action Steps:

- Learn to fight. Boxing and MMA gyms abound in most cities, as do jiu-jitsu and karate dojos. Sign-up, step into the arena, and learn to give (and take) a punch.

- Learn Krav Maga.

- Learn how to throw a dynamite straight punch.

- Participate in amateur boxing matches.

- Start your own Fight Club.

6. Go Hunting

David D.Gilmore, author of Manhood in the Making, calls hunting the male “provisioning function par excellence†because it calls upon all the elements of the code of man — mastery, skill, risk-taking, and even sexuality.

Hunting and fighting are what men are particularly evolved for, yet so few men hunt today. Consequently, we have a society filled with men (and women!) who have neither connection to the food they eat nor any concrete knowledge of the circle of life.

I’ve talked to a few of my friends who never hunted until they were well into their thirties and asked them about their experience. How did they feel during the hunt? What was it like when you finally killed something? All of them said that while most of the hunt consisted of just long stretches of sitting in nature (a benefit in and of itself!), when they finally shot something and came upon their prey, something clicked in them. They didn’t feel bad nor did the feel any elation at killing. It just felt weirdly natural.

Action Steps:

- Go hunting. Not just for game. Dress and eat whatever you kill.

- Learn how to field dress a squirrel.

- Learn how to field dress a rabbit.

- Learn how to make a small game hunting gig.

Further Reading:

- 3 Reasons Hunting Is Food for a Man’s Soul

- A Primer on Bow Hunting

- A Primer on Deer Hunting

- A Primer On Hunting With Dogs

7. Seek Independence, Self-Reliance, and Autonomy

Independence and autonomy have always been key parts of the ancient, universal code of manhood.

Dependency is slavery. A man is able to stand on his own two feet and make his own choices. He is captain of the ship of his life and master of his agency.

Independence takes a variety of forms.

First there’s economic independence. While there’s an argument to be made that it takes much longer in our modern world for a young person to get out on their own these days, for the young man with pluck and determination it’s still very much in the realm of possibility.

If you’re in your teens and 20s, do all you can to prepare yourself to become self-reliant as soon as possible. Learn basic life skills that will allow you to rely less and less on your parents or others. Learn how to take care of your car and your clothing. Learn how to cook and clean up after yourself. Learn how to make a budget and save money.

Avoid debt as much as you can and eliminate it as quickly as you can when you do acquire it. Don’t cumber yourself with consumer goods that provide little or no value and end up stifling your mobility and options in life. As you earn more money, avoid lifestyle inflation. Practice frugality. Live a life of simplicity.

Second, strive for independence from systems and governments. Obviously all of us rely on government and institution-provided roads, utilities, and consumer goods. I’m not saying you need to go live off the grid on a compound. Rather, make it a goal to acquire the skills and knowledge you would need in order to thrive even if these systems and conveniences broke down. Modern society allows men to be careless and clueless; nature is less forgiving. Don’t be like the grasshopper in Aesop’s fable who dances and fiddles during the bounteous summer only to beg for help from the industrious, forward-thinking ants when winter comes. Take survival courses, plant a garden, learn how to hunt, store up food and water, start a fire without matches, etc.

Third, seek autonomy in your work. This doesn’t necessarily mean you have to become an entrepreneur (though that’s a great way to become autonomous). Even if you work a regular 9-5, look for jobs that allow you greater control over your work. You’ll find more satisfaction and happiness as you do so.

Finally, seek to be mentally and emotionally autonomous, too. Avoid any addictions, as well as attachments that fall short of that label, but still diminish your agency. Do you need drugs or alcohol to feel okay or to have a good time? Can you go 10 minutes, an hour, a day, without checking your phone? Can you go a week, a month, a year without porn? Do you live for the approval of women? Do you often “should†on yourself? Do you read the comments on a blog post to figure out how you should feel about it? Do you care uncomfortably much about how many likes your Instagram pic gets? Form your own opinions, make your own decisions, be your own man.

It’s important to note that becoming totally self-reliant is neither possible nor desirable. It’s a balance — no man is an island. As we’ll discuss later, manhood was never a solitary pursuit. Thinking you can either survive or thrive on your own is complete bullocks. It’s about seeking independence and autonomy where you can, not bunkering down all by yourself.

Action Steps:

- Get out of debt.

- Become an autodidact.

- Learn basic life skills.

- Start a garden.

- Start your own business or side hustle.

- Move out of your parents’ house.

- Ask your employer for more autonomy in your work.

- Do an Input Deprivation Week, and maintain your detachment from devices by taking a weekly Tech Sabbath.

- Build a bug out bag.

- Create an emergency food/water/essentials supply.

- Learn survival and first aid skills.

Further Reading:

- How to Become Self-Reliant

- Being Your Own Man

- Go Small or Go Home: In Praise of Minimalism

- Beyond “Sissy” Resilience: On Becoming Antifragile

- The Autonomous Man in an Other-Directed World

- Win the War on Debt: 80 Ways to Be Frugal and Save Money

8. Become Capable and Competent

Throughout cultures and time manhood has always been about gaining cultural competence so you can be effective. To be a man means to be skilled in as many of the tasks as possible that are important for getting ahead in a particular society. Cultural competence is about gaining a breadth of knowledge and proficiencies so that a man can be deft and adroit in any situation he might find himself in. The French have a phrase that encapsulates this idea: savoir faire (pronounced “sahv-wah fairâ€). James Bond embodies savoir faire. Teddy Roosevelt had it in spades, and so did many of our grandfathers (I know mine did). A man with savoir faire can fix a leaky faucet, dress sharp for a black tie event, converse with truck drivers and diplomats, and immobilize an armed attacker. It’s about being a kind of Renaissance man: smooth, smart, handy, and resourceful.

Having savoir faire aides a man in fulfilling his role as Provider and Procreator because it makes him more attractive not only to businesses, but also to women. Moreover, becoming capable and competent is an important part of attaining the goal of independence and autonomy. Plus, knowing you can confidently walk into any situation and know how to act, how to own the room, and how to solve any problem that arises simply feels awesome.

For a man living in a modern, Western, capitalistic democracy, having cultural competence means primarily focusing on “softer†skills that will allow him to excel in our modern economy and sexual marketplace. A man needs to know how to dress well, how to carry on an engaging conversation about a wide range of topics, how to be charismatic, how to manage information, how to give a public speech, how to persuade others, etc. So work on developing those skills as much as you can. While they aren’t called upon as much, it helps to acquire some “harder†skills too – how to use tools, tie knots, fire a gun, change a tire, etc. You never know when such know-how will come in handy.

Developing savoir faire is definitely one of my favorite aspects of manhood (as you know, much of AoM is dedicated to it!). Spending time learning about all sorts of new skills is just plain fun, rewarding, and empowering.

Action Steps (this is just a sampling of some of our favorites – for more, see pretty much the entirety of our archives and become a subscriber!):

- Learn how to shake hands.

- Learn how to be more charismatic.

- Learn how to write an email that will actually get a response.

- Learns the basics of etiquette.

- Learn how to command a room.

- Learn how to make small talk.

- Learn a second language.

- Learn how to tie knots.

- Learn how to change a tire.

Further Reading:

9. Gain Mastery

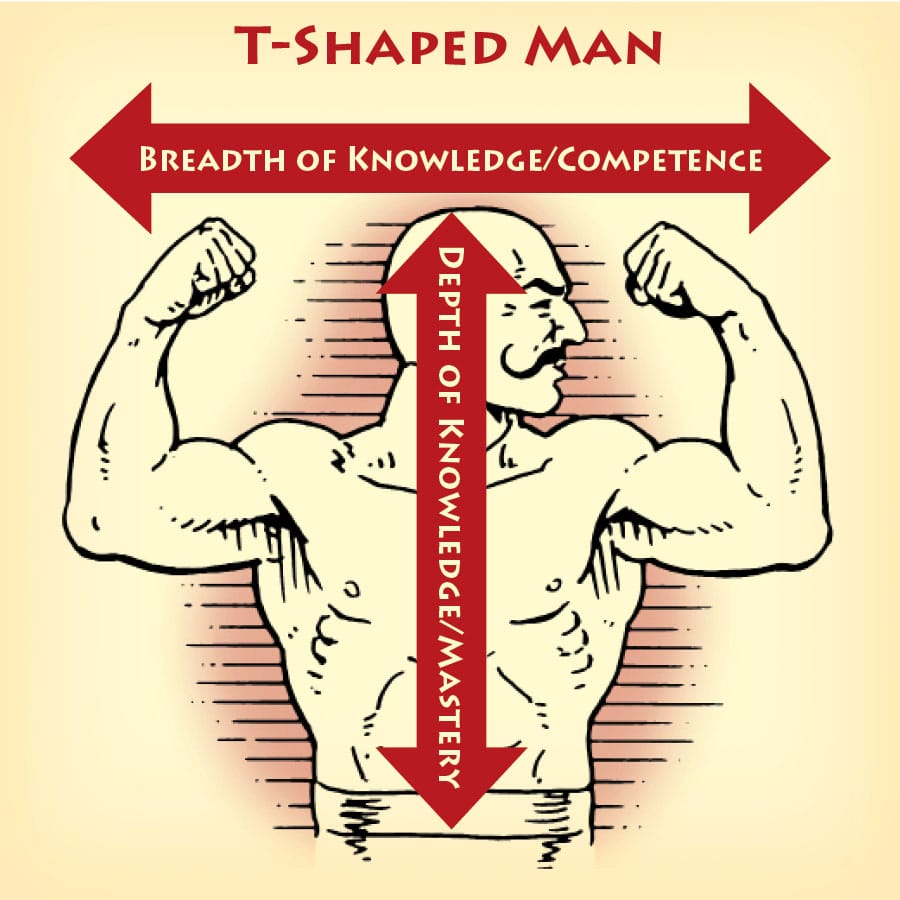

While having a breadth of knowledge is important, having depth in a few skills is also important. Don’t be a “hyphen†or dilettante. These are folks who flit around from one skill or discipline to the next without ever becoming an expert in any of them. They’re the jack-of-all-trades but the master of none. To be truly effective, we need to be Mr. Ts.

“T-shaped†men have a breadth of knowledge, but also have deep knowledge in a specific area. They’re a jack-of-all-trades and a master of one (or two!).

If you’ve spent most of your adult life jumping from one interest to the next without fully immersing yourself in something, make the commitment today to focus your time and energy on gaining mastery. It’s incredibly rewarding in and of itself, but it will also make you more useful, more interesting, and more successful in your vocation.

Action Step:

- I would suggest picking two areas in which to gain mastery: 1) a skill that’s important to your professional life and 2) a tactical skill that’s close to the core of masculinity of fighting and hunting – marksmanship, a martial art, etc.

Further Reading:

- The First Key to Mastery: Finding Your Life’s Task

- Mastery: The Apprentice Phase

- The Secret of Great Men: Deliberate Practice

- Listen to my podcast with Robert Greene, author of Mastery

10. Take Risks and Develop Courage

The ancient Greek word for manliness is andreia; the Latin word for manliness is virtus. In both instances, manliness=courage. The Greeks and Romans weren’t the only cultures to equate courage with manliness. As Gilmore reveals in his cross-cultural analysis of masculinity, courage has been the sin qua non of manhood in every time and place throughout all of human history.

For courage to exist, there must be risk. And so to develop our andreia we must court a little danger in our lives.

As we’ve explored in this series, manhood has always been considered an earned status – an achievement. And just as it can be earned, it can be lost as well. Thus, a manhood that doesn’t risk its dispossession is no manhood at all.

For our primitive ancestors, opportunities to exercise their manly courage through risk were plentiful. Danger surrounded them at all sides in the form of enemy tribes or wild animals. You didn’t have to go looking for trouble, trouble found you.

Contrast that to our modern world in which safety and comfort are plentiful, but risk and danger are wanting. If a modern man wants to experience a visceral life or death risk, he has to purposely seek it out by signing up for military combat or taking part in extreme sports. But even the more subdued forms of risk that men were formerly expected to embrace have diminished. For example, instead of asking a woman out in person or over the phone, men today use technology to blunt and even eliminate the risk of rejection. There’s less sting when a woman ignores your text message than when she tells you “no†to your face.

While we should all find ways – big and small – to court a little danger in our lives, that doesn’t mean our risk-taking needs to be stupid or even excessive. Part of the problem in today’s culture is that we provide and encourage so few positive, pro-social outlets for male risk-taking — particularly for young men. Consequently, we have young men who do needlessly dumb things that provide no real benefits for the man or for society. To make risk-taking rewarding, we need to, as psychologist Nicholas Hobbs puts it, “choose trouble for oneself in the direction of what one would like to become.†Instead of sticking fireworks up your butt and lighting them, start a business, join the merchant marines, take part in an amateur boxing match, or ask out that pretty woman you’ve had your eye on for so long.

Moreover, understand that the amount of risk you take will probably diminish as you enter different stages in your life thanks to naturally decreasing levels of testosterone as well as simply having more to lose than gain. Gilmore notes in Manhood in the Making that in most cultures, risk-taking was encouraged in young men as a way for them to gain the hardihood to tackle the mature tasks of later life. Once a man becomes established and has a family, excessive risk-taking was then seen as boyish and unmanly, because at that point in a man’s life his job was to maintain what he had and gain more.

All of which is to say, that we would do well to seek the Aristotelian mean when it comes to taking risks.

Action Steps:

There are many forms of courage, but physical courage is its highest form, as it requires overcoming our strongest biological drive: self-preservation. As discussed above, the courage one gains in the ring or on the battlefield will extend to one’s moral and intellectual pursuits. But I’m not sure the reverse is true. That is, while taking small risks in moral, social, and intellectual areas will develop your ability to take greater risks in these areas, I’m not sure that turning down a drink to uphold your convictions about alcohol will translate into greater courage to run out under fire. So as you look for risks to take in your life, be sure not to neglect some that involve physical courage.

- Ask a woman out face-to-face.

- Start a business.

- Choose an alternative path to going to college.

- Learn to ride a motorcycle.

- Stand up for your beliefs even in the face of ridicule.

- Take part in sports that involve physical danger (fighting, rock climbing, surfing, snowboarding, etc.).

- Give a public speech.

- Take part in the manly art of haggling.

- Do s**t that scares you and conquer whatever particular fears your have.

Further Reading:

11. Embrace Competition

“With what earnestness they pursue their rivalries! How fierce their contests! What exultation they feel when they win, and what shame when they are beaten! How they dislike reproach! How they yearn for praise! What labors will they not undertake to stand first among their peers!” -Cicero, on Rome’s young men

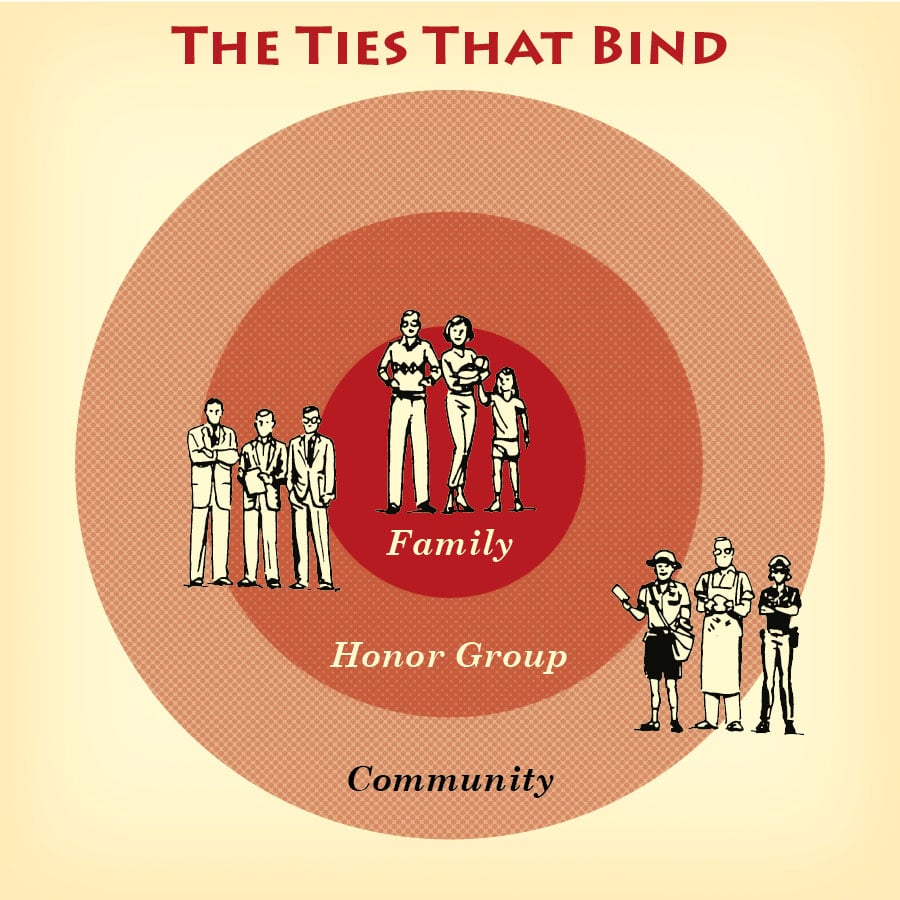

Each of the pillars of manhood involves public competition between men to be the best. Men have always competed for status, to see who could be the superior protector, procreator, and provider. It’s how men gained self-worth and displayed their value to their community, honor group, and possible mates.

Today, however, many social critics bemoan the masculine competitive drive and argue that men and all of society would be better off if we stopped with the “pissing contests†and embraced a more feminine ethos of cooperation.

Hogwash, I say! Hogwash!