I’m something of a homebody. I work at home. I like being at home. I’m not really introverted, just lazy.

So when I get an invitation to a social event, unless some really good friends I enjoy are going to be there, I’m usually not that keen to go. I think about getting ready, and having to make small talk, and being bored, and it’s hard to get jazzed to make the effort.

But sometimes I have to go, and in such cases, I’ve developed a way to approach the obligation with a better attitude: I think of it as practice for a skill I want to keep sharp.

I’ve found that when I don’t practice my social skills regularly, they atrophy; effective sociability is less like riding a bike than speaking a foreign language. The ineptitude that results from such neglect wouldn’t matter if I exclusively found myself at events with people I didn’t care about and will never see again. But every once in a while, I do find myself in social situations of actual import, where I do care about making a good impression. And, alas, I’ve found that I can’t perform well in these latter situations, if I haven’t been practicing my skillz in the former.

So, I try to approach social events I’m not excited about with the mindset that they’re “scrimmages” before the “big game.” A low-stakes workout to keep what would otherwise be flabby social muscles “in shape” and ready for a higher-stakes scenario.

Essentially, I reframe the event in a way that changes how I see it, and feel about it, and ultimately, how I experience it — which becomes more positive than it would have been.

Shifting my frame of reference is something I’ve found helpful not only in this area of my life, but many others as well. While mental reframing is a simple concept, it can have a profound effect on your life too — especially in strengthening your overall resilience to life’s pitfalls, curveballs, and garden variety annoyances.

Events Don’t Create Emotions — Your Beliefs Do

If you’re like most people, you probably have an idea — typically unexamined and subconscious — that events cause emotions.

Meetings at work make you bored. Receiving criticism makes you frustrated. Traffic makes you angry. Talking to women makes you nervous.

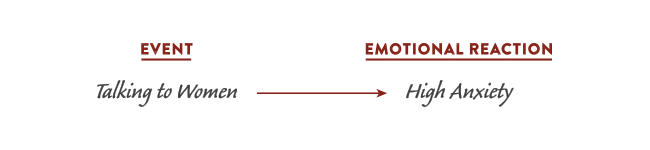

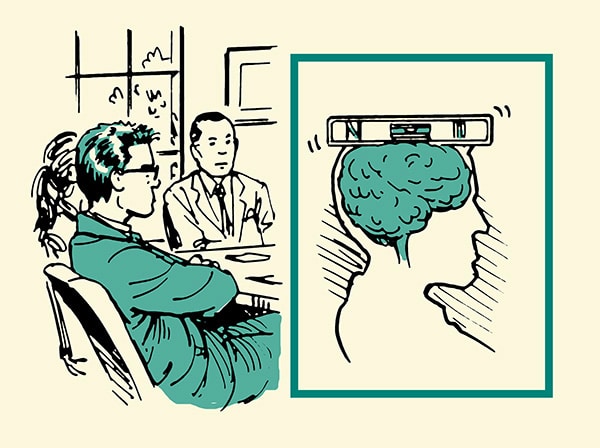

As Alan Garner observes in Conversationally Speaking, the assumption is that there is a direct, linear relationship between events and emotions:

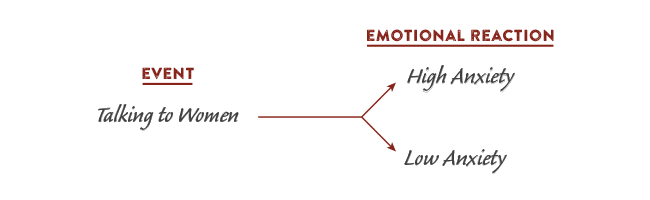

But digging just a little into this idea readily reveals its shaky underpinnings. Think about how two different guys approach women in two different ways, for example.

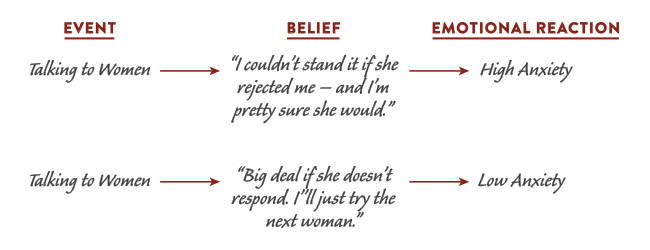

Whenever Jack sees an attractive woman, he goes up to talk to her. He tries to get some conversation going, and if she ignores him, he just shrugs his shoulders and tries talking to someone else.

Andy has had his eye on a pretty gal in his classes all year. But whenever he thinks about talking to her, he feels a pit of anxiety in his stomach. “What if she blows me off and makes me feel like an idiot?” he thinks. “I couldn’t handle it if she did.” At the end of the year, Andy’s crush graduates, and he never sees her again.

For both Jack and Andy, the event/situation is exactly the same: talking to women. But their emotional reactions are exactly opposite:

Clearly then, situations in and of themselves do not cause emotions.

Clearly then, situations in and of themselves do not cause emotions.

Instead, there’s another factor that resides in between the event and the emotions it produces: your belief about the event. It’s your mindset regarding a situation that in fact produces your reaction to it:

Thus, if you want to change your feelings about a situation, you don’t actually have to change the situation itself (which isn’t always possible), or try to avoid it entirely (which can be detrimental); rather, you simply have to change your beliefs about it.

You have to reframe your perspective.

Why Reframing Increases Your Resilience

The idea of reframing your thoughts isn’t a new concept. It goes back at least to the Stoic philosophy of ancient Greece and Rome, as encapsulated in Epictetus’ observation that “Men are disturbed, not by things, but by the views they take of them.”

Reframing doesn’t mean completely ignoring the downsides of situations or being naively Pollyanna-ish in looking for silver linings that don’t exist; it doesn’t require a denial of reality or life’s stressors. Instead, it’s an acknowledgement that reality is, in fact, somewhat subjective. Things really do objectively happen, but the meaning of those things is open to interpretation, and this interpretation changes how you experience them, which changes your reality, which can affect your mental health and how you behave.

Have you ever seen that “optical illusion” drawing where if you look at it one way it’s a pretty lady, and if you look at it another, it’s an old woman? Which is the “real” or “right” way to look at the picture? Either one is entirely legit.

Likewise, there often isn’t one “right” way to look at the things that happen in your life. Much of what is “true” about a situation is up to you, and there are typically several equally valid ways to see something.

Given this fact, it’s obviously most beneficial to come at things from a frame of reference that avoids fueling the negative emotions and negative thoughts that lead to dejection, anxiety, and frustration and stymy growth and action, and instead cultivate one which facilitates positive emotions that work towards building resilience to keep you moving forward.

How to Reframe for Resilience

So how do you go about changing your beliefs/perspective about something?

By asking yourself two questions:

- In what context could this be useful?

- What else could this mean?

The example I shared in the introduction of thinking about less-than-enticing social events as practice for performing well at important ones, illustrates a shifting of context. In the context of fulfilling a mere obligation, the situation holds little benefit for my life. But in the context of sharpening a skill, my attendance becomes more useful, and thus more palatable to me.

If you lose your job, this could constitute a terrible, depressing turn of events that will torpedo your life and well-being. But, what else could it mean? Could it also be an opportunity — a chance to finally start that business you’ve been dreaming about?

Below are some more examples where reframing the context and meaning of life’s twists, turns, and speed bumps identifies a more positive and useful reality, which consequently allows you to react with greater resilience. As you’ll see, coming up with a vivid analogy for the framework of your new perspective can be quite helpful; the process of reframing essentially involves replacing one narrative with another, and the more memorable you make the new story, the more it will stick in your mind, and influence your thoughts and behavior.

Dealing with Setbacks/Rejection

When a project collapses or a girl you ask out says no, or you don’t get a job you were going for, it can feel like absolute failure, and most people believe that failure is a wholly negative thing.

Of course, it’s not. Sure, it definitely feels terrible, and it can involve the loss of money, time, and relationships (potential or real). But failure is never a total wash. You always learn things — about you, about other people, about how things work. It narrows your field of options; you get closer to zeroing in on the technique or solution that will actually beget success. Or it helps you come up with options you previously didn’t know existed. You always end up knowing something after, that you didn’t know before.

Thus, it’s better to look at setbacks and rejection not in the context of failure, but as the conclusion of an experiment.

Indeed, one of the most resilient ways to approach the world is to see yourself as a scientist, and your actions as endless research trials in this lab called life.

Instead of making your every move something you’re wholly invested in (whether emotionally, financially, whatever) that has to work out, just see your decisions as hypotheses, and their outcomes as new data sets to study and learn from. If I do X what happens? If I do Y what happens? Why did experiment X fail? What can I change about the experiment next time to potentially garner a different, and perhaps more successful result? Form a hypothesis, do an experiment, examine the results. If it doesn’t work out, rinse and repeat.

Let’s say, for example, you ask a woman on a date and she says no. Rather than thinking of this snub as a failure, realize that 1) you took action instead of cowering, and should thus gain self-respect, 2) you eliminated a possibility from your mind, so you don’t have to ask “what if?”, 3) you may have stumbled in your approach, but instead of making yourself sick with embarrassment, you can analyze what you did wrong, and figure out how to approach a woman better next time. Each time you talk to a woman becomes a learning experience, where you can discover what works and what doesn’t, and refine your technique over time.

Reframing your approach to life as that of the scientist helps failures to feel less unexpected, less personal, less emotional — just par for the course. It thus enables you to feel confident taking more risks; that’s your job as a scientist, after all!

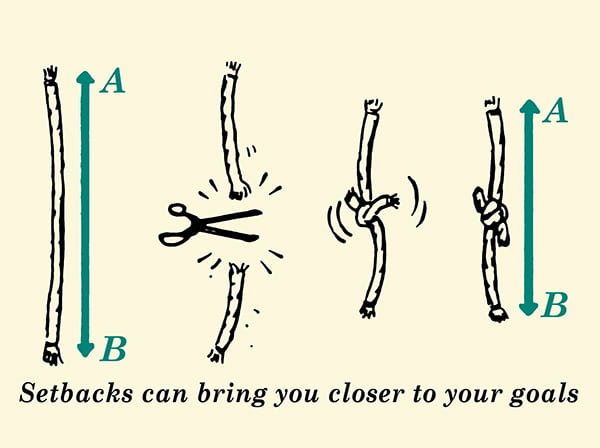

Another helpful way to envision the beneficial nature of setbacks is to see a failure as the cutting of a string that reaches between where you are now and your goal; if you make the effort to retie the string, the distance between your position and your goal shrinks.

Encountering an Annoying/Frustrating/Anger-Inducing Human Being

When you encounter an annoying/frustrating/anger-inducing person, there are a couple different methods you can use to “flip the script” and see him or her through a lens that keeps you from reacting in a negative and possibly destructive way.

The first reframing option is to see the provocation as a chance to hone your patience and willpower. Self-control is like a muscle that can be strengthened through exercise, and an encounter with something that tests it, constitutes just such a “workout.” View keeping your cool as akin to cranking out as many reps as possible on the bench press. You can even see it as playing a kind of game with yourself. When Kate and I “parent like a video game,” we imagine the struggle to stay as Stoic as possible in the face of our children’s misbehavior as a kind of contest between our impulsive, reptilian brains, and our higher-level mastery over emotion. Enjoy the challenge of forcing the latter to come out on top!

If it’s an annoying grown-up you’re dealing with, you can play the How-Stoic-Can-I-Be game with them, or work to change your frame of reference as to what’s causing their headache-inducing behavior. Whenever we do something wrong, we tend to attribute our actions to external circumstances: we’re driving like a crazy person because we need to get to an important interview on time; we act short with our kids because our boss rode us hard at work; we forgot our friend’s birthday because we were running around trying to get ready for a trip that day.

In contrast, we tend to attribute other people’s bad behavior to their inherently flawed character: the guy driving like a bat out of hell is an egoistical maniac; the mom snapping at her kids is a terrible parent; the friend who forgot our birthday is self-absorbed.

Thus, all you have to do if you want to become more patient with people’s foibles, is to reframe their mess-ups in the same flattering light you cast on yourself.

Encountering an Annoying/Frustrating/Anger-Inducing Event

When it comes to things not going according to plan, it’s helpful to change your frame of reference as to how you see life as a whole.

A huge part of what makes annoying events annoying is that we see them as unexpected and unfair. We have a subconscious belief that life should go smoothly, and in just the way we believe we deserve; when these beliefs are violated, we flip out.

Expectations are the king of our reality: When you’re hoping for an A on a test and get a D, you’re devastated; when you thought you’d get an F and instead get a C, you’re thrilled. If your girlfriend dumps you, and you thought you’d be together forever, you’re devastated; if she saves you from doing something you had been working up the gumption to do yourself, you’re thrilled.

Far better it is then to set reasonable, rational expectations for things; in terms of one’s expectations for life, you change your belief that things will usually go according to plan, since in reality, they so rarely do. Unexpected twists and turns should be readily and zen-fully anticipated.

So too, life just isn’t fair. The universe doesn’t owe us anything; we should be more surprised about how much good regularly comes to us, rather than put out by more occasional omissions and withdrawals.

Receiving Criticism

Receiving feedback, no matter how well-intended, is never easy. And when it isn’t well-intended, and craps all over who you are and/or what you do, whew, that can send your motivation plummeting, and your anger soaring.

One way to deal with criticism that does have merit, is to reframe it as the symptom of some “disease” you need to address; as Winston Churchill wisely put it: “Criticism may not be agreeable, but it is necessary. It fulfills the same function as pain in the human body. It calls attention to an unhealthy state of things.” That which the feedback causes to throb, is that which needs to be excised with a knife, or healed with a salve. Criticism is a chance to see where you can improve and get stronger.

If a critique or insult doesn’t have merit, view its origins not as being caused by what you’ve done, but as an effect of it. Doing anything that has an impact garners attention and brings you more into the public eye; the more impact you’re making, the more brightly the spotlight shines. And, since nothing anyone does ever finds favor in 100% of people’s eyes, opposition is inevitable.

Thus, when you find yourself coming under fire from peers, associates, or the public at large, see such missives from the peanut gallery not necessarily as an indication that you’re doing something wrong, but as evidence that you’ve stepped “into the arena” and are taking action, rather than following the path of least resistance, and playing it small, like the majority of folks are wont to do. As Elbert Hubbard famously put it, the only sure way to avoid criticism is to “Do nothing, say nothing, and be nothing.”

Feeling Stressed Before an Event

Stress gets a pretty bad rap.

It’s charged with causing heart attacks, obesity, and sicknesses of all kinds. Plus, most people simply don’t think it feels very good, what with all the adrenaline pumping, cortisol releasing, blood vessel dilating, glucose discharging, heart rate amping, pupil expanding effects it causes. They often blame this physiological thunderstorm for sabotaging their performance.

But our beliefs are partly wrong about stress, and our negative perception of it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Certainly, chronic stress — living a life that induces a strong stress response day after day — can have deleterious effects on one’s health, regardless of how good your health care is.

Stress can debilitate one’s performance as well.

But, when it is activated as intended — in response to dealing with occasional, short-term events — and viewed in a positive way, stress can in fact enhance both your health and your execution of high-stake activities.

The charge that stress applies to one’s hormones and nervous system are designed to improve your body’s physiological and psychological functioning, so that you can perform at your best in situations that will stretch your mental and/or physical capacities. The stress response focuses your attention and energies on the task at hand.

It’s because of these performance-enhancing qualities that neuroscientist John Coates argues that the stress response should really be called “the challenge response.”

In fact, research has found that stress isn’t just good for your external performance, but for your inner health as well, and “can fuel physiological thriving by positively influencing the underlying biological processes implicated in physical recovery and immunity . . . the experience of stress elicits anabolic hormones that rebuild cells, synthesize proteins, and enhance immunity, leaving the body stronger and healthier than it was prior to the stressful experience.”

Researchers refer to the fact that stress can either be a positive or negative thing as “the stress paradox.”

So how do you experience stress as enhancing rather than debilitating?

It’s all about how you channel it, and that comes down to the mindset you have about stress. Yup, your beliefs and expectations again. Studies show that when people simply think that stress is a positive force, it becomes such, having a salubrious effect on health, elevating performance, and leading to greater personal growth. Regardless of the amount of stress experienced.

So the next time your heart starts racing, your breathing gets heavy, and you feel butterflies in your stomach before beginning a job interview, taking the field, or asking someone out, instead of thinking that your body’s telling you not to do something, or that it’s a sign you’re going to fail, or that your nerves will sink your chances, imagine that your body is simply powering up to meet the challenge at hand. Your senses are heightening. Your mind is sharpening. Your energy is increasing. Your body’s getting ready to go into a fight, and come out on top.

The fact that you’re nervous signals that you’re doing something meaningful instead of being a passive spectator — that you’re truly invested in something. It’s a sign not of something bad, but that you’re about to do something out of the ordinary. It’s evidence you’re alive.

Sitting Through a Boring Event

Now that we all carry limitless, instant entertainment centers in our hands, situations that are low on stimulus and that ban or discourage phone-twiddling, seem all the more tedious. Our monkey minds cry out for the ability to swipe through thousands of digital voices and images, while IRL a single monotonous one drones on and the backdrop remains stubbornly fixed.

Being at a boring meeting, lecture, or church service can seem like a waste of time, and this attitude only deepens our feelings of disgruntlement and malaise.

Reframing can help alleviate this funk, at least a little.

Try thinking about the fact that your mind is constantly bombarded by input and noise during 98% of the other waking hours of your life. See the situation as an opportunity to recalibrate your fragmented attention span. Try to really focus on what the speaker is saying. Come up with interesting questions you could ask them (even if you’re sure they wouldn’t have interesting answers). Or use something they said as a jumping off point to have your own session of personal contemplation. Or, just stare at the wall, attempting to keep your mind concentrated on tracing the contours of the spackling.

Maybe the speaker or teacher won’t end up imparting a new insight to you, but at least you’ll walk away feeling a little more mentally centered.

Conclusion and Caveats

Mental reframing may seem like a squiggy exercise in positive thinking — a “Is the glass half full or half empty?” cliché — but it’s rooted both in ancient philosophy and modern empirical research. Over and over again, studies have demonstrated the huge effect mindset can have on behavior, psychology, and well-being. To cite just a few examples: people with a negative perspective on aging are less proactive about preserving their health and die sooner; students who believe intelligence is malleable rather than fixed increase their motivation, improve their GPAs, and enjoy learning more; housekeepers who think of their work as also being good exercise lose more weight than those who see it only as work.

Mindsets matter.

If you feel like stuff happens to you, and that events/situations cause your emotions, you’re not going to feel very in control of your life. You’re not going to be very resilient.

It’s empowering to realize that you can change your beliefs about things — that the frame you choose will determine how you react to situations/events, how you experience them, and ultimately your whole reality. Reframing is about more than looking at things in a positive light; it’s about intentionally choosing the path of most growth.

The examples cited above are just a sample; you can reframe just about everything, as just about everything has more than one legitimate context and meaning. You are free to choose the one that is most useful to you. As you do so, work to come up with a vivid analogy for this new frame of reference — a new narrative that will help it stick in your mind.

Just remember that life should never be reframed in ways that seek to take the responsibility that belongs to you, and place it on someone else. It should never be about making excuses, or lying to yourself, or avoiding negative but legitimate feedback, or trying to form a reality out of materials that objectively do not exist. After all, you can be “in the arena” but still be acting like a clown that people are rightfully throwing peanuts at, and seeing yourself as a warrior in a noble fight does not automatically make it so.

Reframing thus requires greater self-awareness, not less.

In general though, every problem is also a challenge; every setback is also an opportunity; every situation that fails to stimulate one capacity provides practice for another. Everything’s got something to teach. As long as you’re looking at it through a framework of learning.

______________________

Diagrams in the “Events Don’t Create Emotions” section taken from and inspired by those in Conversationally Speaking by Alan Garner.

Illustrations by Ted Slampyak