Welcome back to our series on male status. This series aims to help men understand the way status affects our behavior, and even physiology, so we can mitigate its ill effects, harness its positive ones, and generally get a handle on how best to manage its place in our lives.

In our previous article in this series on male status, we discussed some of the forces that have shaped the cultural evolution of status in the West. Urbanization, Christianity, monogamy, and the Enlightenment all contributed to the development of a greater sense of self and individuality, and the weakening of the walls of status hierarchy. Whereas prior to the 18th century, status had largely been hoarded by a few families who had amassed great riches, and passed those resources on from generation to generation, more paths to power and wealth slowly began to develop. New industries and career options multiplied during the 19th century, allowing men with varying talents to attain status in an expanding number of niches.

This diversification kicked off a transformation in the meaning and routes to status that would fairly explode over the course of the next century. Professor of philosophy Steven Quartz argues that the pathways of status moved through 3 stages during this time: from hierarchical, to oppositional, to pluralistic. Today we’ll take you on a tour through these stages of status evolution, and explore how being “cool” became the major preoccupation of the 20th century.

19th Century to the 1950s: Traditional Hierarchal Status

While the 19th century saw the rise of new paths to status, the prerequisite of that status remained fairly steady and one-dimensional: wealth. Certainly artists, philosophers, and scientists who brought great works and new knowledge to society, and yet weren’t materially rich, were honored and recognized. But typically even creative and intellectual types desired mainstream fame, and the material rewards that came with it.

Wealth conveyed status not simply for its resource value alone, but also because of the traits and behaviors that society supposed undergirded its attainment. This was the era of the Victorian honor code, in which economic success was connected to moral rectitude. Qualities like industry, frugality, and self-control were thought to be prerequisites to getting ahead. And in many ways they were, and not simply for the practical benefits a disciplined work ethic provided. A man with a sullied reputation would have trouble furnishing the letters of recommendation that were often necessary to be hired for many jobs. A reputation for moral virtue gave a man status in and of itself — even before it had been turned into economic success — as it was considered a valuable resource that could someday be transformed into such success.

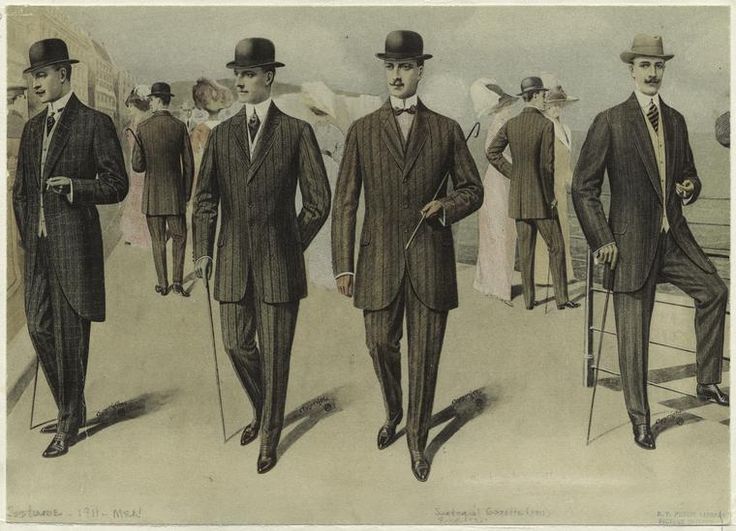

Once wealth had been attained, it was demonstrated materially to others. The growth of large, anonymous cities made the display of social signals that could be read quickly and from a distance more important than ever. Consumer goods of course fit this bill well. A person’s clothing and possessions allowed strangers to assess their place on the social ladder with only a glance. And the rise of mass production at the turn of the 20th century ensured there were plenty of goods available to choose from and new ways to show your neighbors you had made it.

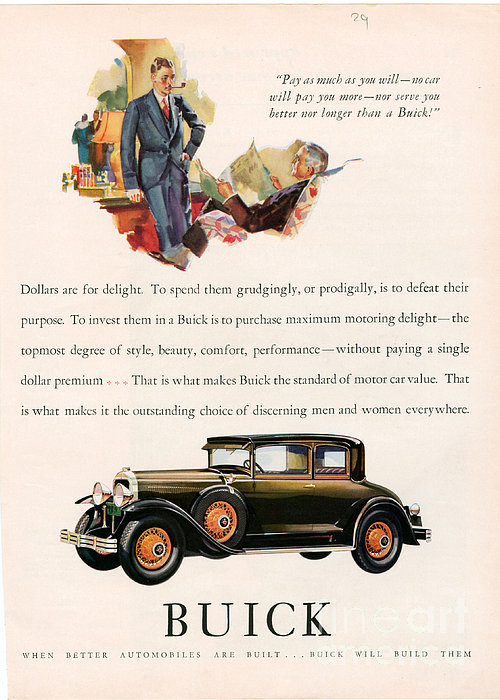

Of course social signals are useless if those who see them don’t understand their meaning. Thus, the rise of mass production and consumption went hand-in-hand with the advent of mass advertising. Anywhere one went in America, one knew that a man with a Model T or a woman with a motorized vacuum was on the up and up.

Within the ranks of the well-off themselves, status was indicated through more complex rules that went beyond simply owning certain possessions. One had to know the proper etiquette of one’s class and be able to show off one’s taste and refinement in things like dining, conversation, and the arts. And even one’s “ascribed†or inherited status mattered. To attain the highest status, it wasn’t enough to have a certain set of possessions, or even the bank accounts to buy them. History and lineage still gave you a leg up when turning your nose up. Hence, the disdain of the old rich for the new.

As the 20th century progressed and society became increasingly democratized, secularized, and diverse, the importance of one’s family name, as well as the connection between wealth and morality, weakened. While the number of routes to status increased, so did competition, as more and more men were free to pursue economic wealth along the same pathways. The rise of “Social Darwinism,†the feeling that it was a dog-eat-dog world, and the spectacle of gangsters and other criminal rogues who had seemingly attained great wealth without following the rules, created a culture where it became more acceptable to do whatever one had to in order to reach the top.

So too, the importance of having a sterling personal reputation became less important in an increasingly anonymous and mobile world. Rather than a letter of recommendation getting your foot in the door, you needed to impress and charm a potential employer who was meeting you for the first time and knew little of your background. Thus, cultivating positive personality traits became more important than cultivating character.

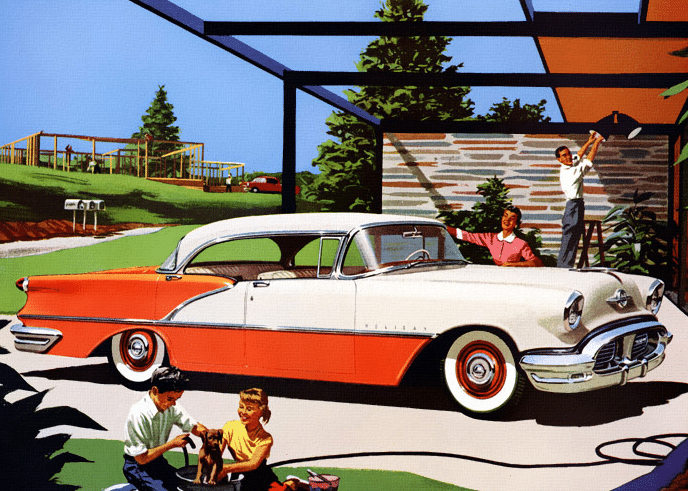

A hierarchy based mainly on wealth and demonstrated through conspicuous consumption remained the dominant status structure through the mid-20th century, at which point it both broadened and intensified. The post-war economic boom lifted many boats into the middle-class, and drove an explosion in consumer goods by which the newly well-off could display their status. Advertisements were filled with wonderfully evocative images of a suburban paradise in which shiny new cars were parked in every driveway and kitchens were filled with modern appliances.

Yet at the same time that consumption opportunities exploded, a more democratic, DIY, middle-class-celebrating dynamic shaped that consumption. Ostentatious displays of wealth — popular with the “robber barons†at the turn of the century — were out, as was the hiring of butlers, servants, and other domestic help. It showed higher status to make one’s consumption conspicuous, but controlled, than to unduly show it off.

The good life had never seemed so attainable, but there were some still unable to climb the status ladder at all, and others who were beginning to think it wasn’t a ladder they wanted to climb in the first place. Both groups would begin to tear down the traditional route to status — creating new pathways that were oppositional rather than hierarchical, and giving birth to our conception of “the cool.â€

The 1950s & 60s: Oppositional Status and the Rise of Rebel Cool

Sociologists posit that humans and primates share a common impulse — the instinct to rebel in the face of perceived domination. In a chimp colony, low status chimps will generally accept their position and go along to get along. But if an alpha starts treating his subordinates too harshly, beta chimps will sometimes band together and stage a coup to topple him and institute another in his place.

A similar dynamic has been observed in humans. People will take a certain amount of oppression in exchange for physical and economic security — when it seems rebellion isn’t worth the risk of increased vulnerability. But in two paradoxically divergent scenarios — utter desperation and comfortable prosperity — people will rise up and push back against the forces keeping them down.

In times of consistent (but not desperate) scarcity, when resources are hard to come by and must be defended from external threats, societies tend to revert to a stricter hierarchical structure. Such power structures provide less freedom, but are more effective for maintaining order and security; everyone knows and carries out their role. In a post-scarcity culture, on the other hand, in which resources are abundant and external threats are negligible, there is more leeway for everyone to march in their own direction. Low status people feel freer to challenge elites, while those on top feel less inclined to crack down on such uprisings.

So it was in the secure prosperity following WWII that two movements of rebellion began brewing. The post-war boom lifted many into the middle-class, but the wave did not reach all groups equally. Minorities, who were resigned to the bottom of the status hierarchy, were legally and institutionally blocked from ascending to higher ranks on the ladder. Women, who had been assigned by default to whichever rung their husbands managed to attain, wished to have more autonomy and an opportunity to seek status on their own terms. Thus was born the civil rights movement, in which formerly marginalized groups agitated for both equal status as citizens, and the chance for an unfettered rise up the traditional status totem pole.

On the other side, you had largely white, middle- and upper-class men who were well-positioned in the traditional status hierarchy, and couldn’t claim to be unfairly dominated by the existing power structure. Yet they felt that the structure had created a culture that was itself too dominant, conformist, and stultifying. They weren’t looking for an easier path up the ladder, but rather eschewed the desire to climb the ladder altogether.

To move up the traditional status hierarchy, those on the lower rungs seek to emulate those above them. But since there’s only a limited amount of status available, it turns into a zero sum game; to rise higher, you’ve got to knock down someone above you. Furthermore, as soon a lower strata adopts a certain set of behaviors or goods from the upper strata, those on top abandon those behaviors or goods for new ones that will more clearly signal their distinctiveness and wealth. This forces those below to buy those things too, and on and on the cycle goes. Quartz calls this dynamic the “Status Dilemma.â€

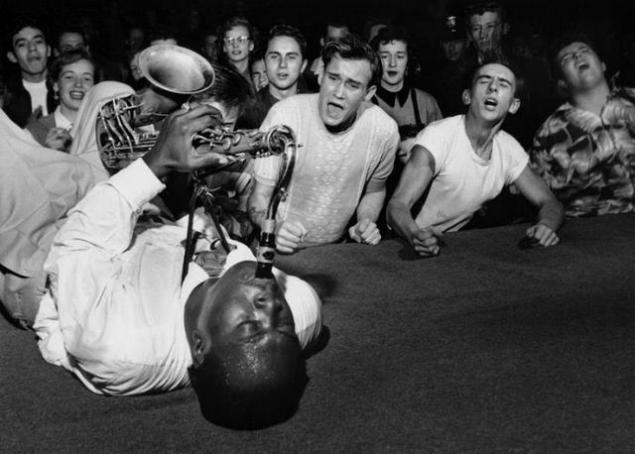

The beats and then hippies of the 1950s and 60s wanted to throw a wrench into this merry-go-round. They inverted and subverted the traditional status hierarchy by appropriating the values and culture of those on the bottom — African-Americans, blue collar laborers, and drifters of all kinds. These types were celebrated in the idea that though they were poorer and more oppressed, they operated outside the conformity of mainstream society. Just as importantly, they were more virile and masculine than the emasculated cogs content to sublimate their passions to the corporate machine. Quartz marks this inversion of the status hierarchy as the birth of “Rebel Cool.â€

With Rebel Cool, status came not through wealth and striving to become a “man in the gray flannel suit,†but in the amount of scorn you got from the dominant culture. The more you didn’t give a f**k about what mainstream society thought about you, the more status you gained from your fellow nonconformists. If wearing a leather jacket, riding a motorcycle, and listening to rock n’roll upset your parents and preacher, that was cool.

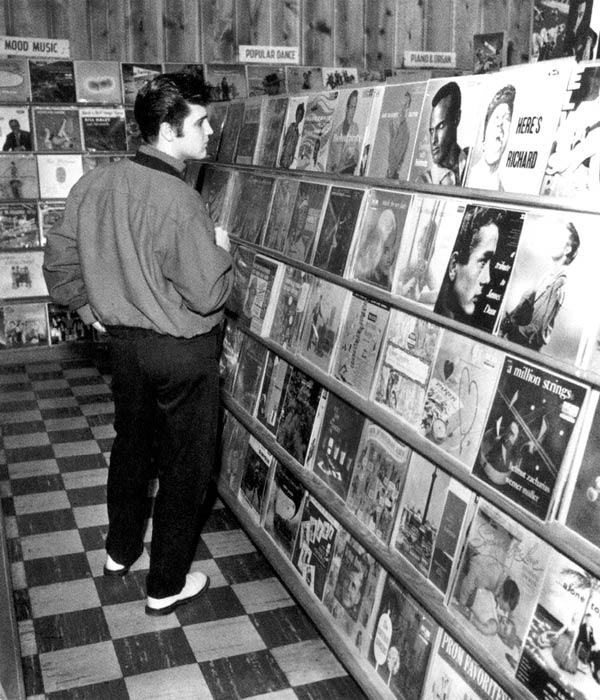

While being cool ostensibly began as a rebellion against consumerism, consumerism is what ironically allowed it to take off. Mass production and mass media delivered wearable, watchable cool in the form of rock’n roll albums, leather jackets, motorcycles, and movies like The Wild One. Almost as quickly as cool arose as an attitudinal cultural stance, it became a purchasable “lifestyle.â€

Fueling the rise of Rebel Cool were shifts in psychological thinking. The principles of Freudian psychology had dominated the early part of the 20th century; the mainstream view of the mind was that it was filled with animalistic and contradictory impulses, which induced anxiety and neuroses and had to be sublimated in productive ways for the good of society. New “renegade†psychoanalysts, however, were beginning to posit an opposite view — that the repression of one’s emotions and sexuality is what was really making people unhappy. People needed to throw off their social conditioning, express their feelings directly, and have as many orgasms as possible.

Rebel Cool thus expanded to include all kinds of self-expressive avenues that had previously been curtailed by mainstream societal norms. Hippies, who had taken the beats’ baton and ran with it, grew their hair long, experimented with drugs, and engaged in plenty of casual sex. Hippies and their sympathizers also rebelled against the conspicuous consumption they had grown up with. The emerging Left disdained the way corporations and advertisers had for decades employed Freudian psychology to peddle their products and entice customers — forming focus groups that asked participants to free associate about products and targeting ads at people’s unconscious desires and fears. This, the cry went, was tantamount to rank manipulation — brainwashing which was turning citizens into corporate tools.

Erhard Seminars Training — a famous weekend course in which participants were challenged to throw off artificial roles that had been imposed by society, and become their real selves. And to roll around on the floor and scream out their emotions.

If psychoanalysis had repressed one’s healthy emotions and desires, and its use by advertisers had reduced people to expressing their feelings and identity through material objects, then the answer was to strip one’s mind of these implanted ideas — tearing back these false layers in order to find one’s true self and then expressing that self apart from consumerism.

This idea naturally struck fear into corporations who worried that young people’s rejection of mainstream culture and old school consumerism might torpedo their bottom line.

As it turns out, they needn’t have worried.

1960s to the 1990s: Oppositional Pluralistic Lifestyle Status

The paths of the civil rights fighters and the self-expressive rebels would come together and become intertwined. Minority activists increasingly rejected hegemonic social norms and embraced new ways of expressing themselves, often looking to their cultural heritage for inspiration. At the same time, the cool white kids often got involved in social activism and joined the fight for civil rights. Together these groups formed the counter-culture movement.

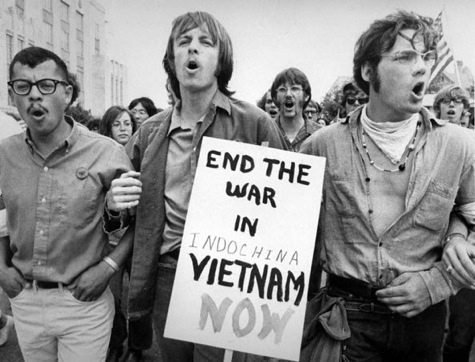

The initial goals of the movement were to truly transform society — to fundamentally alter economic, cultural, and political institutions in order to create a new, more liberated, egalitarian, inclusive, creative, expressive, and peaceful culture. This fight had two fronts — external and internal. The rebels would protest and work to institute new laws, while also opposing the status quo through personal self-expression that countered traditional mores and norms.

The movement made many strides, but when it eventually ran into armed resistance from the state — riots outside the ’68 Democratic Convention; shootings at Kent State — wholly toppling “the man†began to seem like an impossible goal.

Motivation for waging battle on the external front thus waned, and a new guiding principle for the movement emerged. Rather than concentrating on activism and fighting corporations and the state directly, it might be better, the thinking went, for each person to focus on improving themselves. If you couldn’t topple the dominant economic and political systems, then you could still work to remove their social controls from your mind. As each individual got healthier and happier, and made their way into positions of power, society would slowly transform from the inside out. The political became personal.

This impulse gave rise to the human potential movement in which individuals were encouraged to dive deeper and deeper into the self in order to discover their true identity. Since concentrating on oneself might ostensibly lead to a better society overall, such introspection and search for positive self-esteem wasn’t considered a selfish pursuit, but rather one’s highest duty.

But as the idea of self-actualization — of becoming the best possible you — took hold, collective concerns began to be forgotten altogether. Personal happiness became paramount, while changing society began to seem pointless and irrelevant. And what started as a challenge to state and corporate power, ended up playing right into their hands.

Advertisers were initially flummoxed as to how to market to this new generation of self-actualizers who declaimed an interest in mainstream, “conformist†consumerism. But they soon realized that what seemed like a threat to business, was in fact a huge opportunity.

What marketers found is that while the rising generation was indeed uninterested in mass-produced products, they were quite keen on purchasing goods that expressed their individuality. Having spent time and effort in discovering their true self, they wanted to be able to express that self to others.

One thing the countercultural movement was very successful in, was creating the freedom for people to live in different ways. But to their relief, marketing researchers found that while the perception was that everyone was now marching to the beat of their own drummer, modes of self-expression were in fact not infinite and could be sorted into identifiable types. This was true even among those at the top of the self-actualization hierarchy — those who were “inner-directed†and sought to make their own choices apart from societal pressures.

Using just a 30-question survey, researchers found the entirety of the American public could easily be sorted into a dozen or so different categories based on patterns of behavior. These patterns were dubbed “lifestyles,†and included groups like the “I-Am-Me’s†(“searching for new values, breaking away from traditions and inventing their own standardsâ€) and the “Experientials” (“seeking inner growth through new experiencesâ€).

Each identifiable type manifested a predictable purchasing pattern, giving rise to “lifestyle marketing.†Advertisers learned how to surround their products with the values that resonated with different lifestyles, so that consumers could readily identify which products were “for them.†At the same time, new technologies allowed companies to cost-effectively manufacture products in a variety of different styles. In the days of mass-production, Henry Ford famously quipped that “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black.†Now, vehicles not only came in a rainbow of hues, but could be had in sporty, rugged, or sleek builds, and customized in a variety of ways. Infinitely expanding options allowed consumers to make purchases that felt like expressions and extensions of their personal identity.

Lifestyle-oriented products and marketing fundamentally changed the landscape of consumerism and the use and meaning of goods as social signals. Whereas consumer goods had formerly been used as signals of wealth, they now became markers of one’s values and personality, and symbols of the lifestyle tribe with which you claimed membership. While we often think of things like how we dress, what car we drive, and what music we listen to as choices designed to express our individuality and set us apart from others, consumption is also a social impulse. It identifies us as part of certain group, and builds bridges to others within that group.

These lifestyle tribes essentially formed new alternative routes to status. Rather then having to work one’s way up the dominant social hierarchy, now you could attain status through membership in a diverse array of different social niches — each with their own values. This type of pluralistic status came in two forms. First, you got status simply by identifying yourself with a certain lifestyle. This kind of status is better termed as collective esteem. “I’m a liberal environmentalist.†“I’m a conservative NRA member.†“I’m a break dancer.†“I’m a punk rocker.†Second, you could gain individual status by demonstrating excellence in the traits important to your particular group. Maybe you chained yourself to a tree to keep it from being cut down, or you won your local breakdancing competition.

With a pluralistic status system, you don’t have to compete directly for status with the mass of humanity. Status is no longer a limited resource, and can in fact expand nearly infinitely. To grasp how this works, it’s helpful to think about the world of sports. In the 1896 Olympics, nine sports were represented, and only athletes who excelled in those 9 sports could gain status. Today, the Olympics includes 28 sports, which means the opportunities for athletes to gain status in their respective niches has increased threefold. And of course still more athletes can compete for status in the X Games or even on the Quidditch field.

Or think about the modern high school. In the 1950s, there was one main route for young men to gain status in that social hierarchy — by playing sports. Jocks and cheerleaders ruled the school, while other types of students were marginalized. Today, high schools bear little resemblance to the stereotype still sometimes trotted out in popular culture, where the strapping quarterback gives noogies to the nerds. There are routes to status for everybody — acting in theater, singing in the glee club, playing hackey sack with the druggies, doing Bible study with the super Christians — and each group is usually cool with the others. Students find their identity and status within these niches, rather than competing with everyone to be “king of the school.â€

The grunge music scene of the 90s represents well the final dissolution of the ethos of Rebel Cool. It was right at the tipping point where authentic rebellion was becoming self-aware irony. What was “alternative” and what was “mainstream”? This is encapsulated well in Cobain’s description of his “Smells Like Teen Spirit”: “The entire song is made up of contradictory ideas…It’s just making fun of the thought of having a revolution. But it’s a nice thought.”

Up through the 1990s, all the different lifestyle groups that had emerged in the decades prior still had the whiff of Rebel Cool about them. Part of the status of embodying them remained oppositional — that one was doing one’s own thing rather than conforming to the hazy and increasingly merely symbolic memory of mainstream culture during the 1950s. Raves, profanity-laden music, sacrilegious art displays, and the like could still incur a reaction from the remaining defenders of traditional culture. But as society became more and more diverse, it became increasingly difficult to locate a conformist boogieman against which to set oneself in opposition. Society had become so fragmented, no true mainstream culture existed. Rebel Cool’s dying breath manifested itself in alternative grunge music, and then passed from the scene to the strains of the Backstreet Boys.

Conclusion

The Baby Boomer generation found a way to form an unlikely combination of capitalism and consciousness, Reagan and Woodstock. They became what writer David Brooks calls “Bobos”: bourgeois bohemians. They adopted a suburban, middle-class lifestyle, but retained a feeling of individuality, self-expression, and “rebellion†by driving a SUV instead of a minivan, buying organic and eco-friendly products, and making a yearly donation to the Sierra Club.

It’s easy to criticize and lampoon the way in which the counter-culture movement was co-opted by capitalism. But as we’ll see, while the pluralistic, consumer lifestyle-oriented status system generated a number of serious drawbacks, it did result in some positive effects in regards to status. So too, Millennials have largely followed in their Bobo parents’ footsteps, though in ways they don’t always acknowledge and recognize. A prompt for reflection in the form of a discussion on the nature of status amongst my own generation, coming up next.

Read the Entire Series

Men & Status: An Introduction

Your Brain on Status

How Testosterone Fuels the Drive For Status

The Biological Evolution of Status

The Cultural Evolution of Status

The Rise and Fall of Rebel Cool

A Cause Without Rebels — Millennials and the Changing Meaning of Cool

The Pitfalls of Our Modern Status System

Why You Should Care About Your Status

A Guidebook for Managing Status in the Modern Day

____________________________________________

Sources and Further Reading:

The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History

Cool: How the Brain’s Hidden Quest for Cool Drives Our Economy and Shapes Our World

Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There