This article series is now available as a professionally formatted, distraction free ebook to read offline at your leisure. Click here to buy.

Welcome back to our series on manly honor. In my last post, I explained the classic definition of honor: having a reputation worthy of respect and admiration in a group of equal peers. This reputation consists of both horizontal honor (your acceptance as a full member of the group), and vertical honor (the praise you receive from excelling more than other members within the group). This type of traditional, manly honor is a very public and external thing. It requires a man to belong to an honor group and suffer social consequences for not living up to the group’s code. When primitive tribesmen, knights, and the Founding Fathers spoke of great honor, this is the type of honor they meant.

Over the centuries, for a variety of reasons we’ll explore today and next time, this traditional conception of external honor evolved into our modern idea of private, inner honor – a type of honor with synonyms like “character” and “integrity.” Today, a man’s honor isn’t determined by a group of his peers conveying high respect, rather, it’s a very personal thing judged only by himself. Nineteenth century German statesman Otto von Bismarck captured this idea of private honor perfectly when he said in a speech:

“Gentlemen; my honor lies in no-one’s hand but my own, and it is not something that others can lavish on me; my own honor, which I carry in my heart, suffices me entirely, and no one is judge of it and able to decide whether I have it. My honor before God and men is my property, I give myself as much I believe that I have deserved, and I renounce any extra.”

In today’s post, I’m going to begin an exploration of why this change from public to private honor occurred. The transformation was a long and complicated process, involving several political, philosophical, and sociological changes in the West. While I initially hoped to explain this history in a single post, the amount of dense, important information to cover really requires two. In part one, I covered how the seeds of honor’s dissolution began to be sown all the way back in Ancient Greece and continued through the Romantic Period. Then in part two next week, we’ll see how those seeds came to full fruition during the modern era — beginning with the Victorian Era and leading up to today.

A Brief Road Map on Where These Avenues Are Leading

Before we set out on this romp through the history of honor (and dishonor), here’s a short primer on how all of the factors that will be discussed tie together.

There are two main factors that weakened the traditional idea of honor. First, over time honor became based not on courage and strength, but on moral virtues. Honor could have continued in this state – your public reputation could have been based on your honor group’s judgment of whether you were living a moral life (this state of honor was last seen during the time of the Victorian gentleman, which we’ll discuss next time.) But in honor’s evolution, being the recipient of great respect wasn’t just premised on moral virtues, it also became completely private – every man could create his own, personal honor code and decide for himself what honor means, and only he himself could judge whether or not he was living up to it. This dissolved any sense of a shared honor code (“to each their own!”), which meant shame also disappeared – there were no longer any consequences for flaunting the code of honor.

As just mentioned, in this post and the next, we will get into the political, sociological, and philosophical changes that fueled these two factors. While it may be tempting to read these posts as saying that these cultural forces are bad, and that personal honor is bad, my goal is rather to simply delineate as objectively as possible why the traditional ideal of honor disappeared and was supplanted entirely with private honor, and then, to argue that private and public honor need not be mutually exclusive, and can, and should coexist.

From Public to Private Honor: Ancient Greece to the Renaissance

Ancient Greece

While it’s easy to assume that the decline of public honor and the rise of private honor is only a recent phenomenon, the seeds of honor’s transformation from a public to private concept were actually sewn at the beginning of Western civilization.

In societies without formal legal systems, honor serves as a rough enforcer of justice as the desire to be held in high public esteem kept what was considered bad behavior in check. Thus, democracy and the rule of law, two important developments to come out of ancient Greece, are in some ways contrary to traditional honor and made it less vital to the functioning of a community.

This early conflict between traditional honor and democratic ideals was actually the principal theme in a trilogy of Greek tragedies written by Aeschylus. The Orestia recounts the curse that befalls the family of King Agamemnon after he returns home from the Trojan War. A series of inter-familial murders, all in the name of avenging and defending the honor of one slain family member after another, comes to an end when the goddess Athena establishes a jury trial to try Orestes for the murder of his mother. Personal and familial honor is replaced by obedience to democratic law as the governing force in Greek society. This isn’t to say that honor and revenge killings stopped occurring after the establishment of democratic juries, but they did begin to be more frowned upon.

Playwrights weren’t the only ones questioning traditional, public honor. The philosophers Socrates and Aristotle raised concerns about the ideal in some of their teachings. For Socrates, it was better for the collective that he subject himself to the rule of unjust state laws than to maintain his honor, or reputation, among his friends by escaping his execution. According to Socrates, concern for reputation was something only for thoughtless men. What mattered to the great philosopher wasn’t the opinion of others (the basis of traditional honor), but rather knowing he lived according to what he thought was just. Put another way, Socrates chose integrity to his personal ideal over the public honor of his followers.

Aristotle showed a similar disinterest in the opinion of others. While he spoke of honor as an external good in his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle was uncomfortable with the idea that it be based solely on the opinion of others. Rather, Aristotle made a tentative argument that honor be based on attaining personal virtue. Excellence meant fulfilling your potential. Instead of being loyal to a group’s code of honor, it was more virtuous to be loyal to virtue itself.

Early Christianity

Three aspects of the rise and spread of Christian philosophy would have a huge impact in weakening honor as a cultural force in the West: 1) its inclusiveness and universality; 2) its emphasis on inner intent rather than outward appearances; and 3) its pacifism.

Inclusiveness and universality. Traditional honor is exclusive. Not everyone is welcome to the club and the code of honor doesn’t apply to everybody – just members. Christ and his disciples taught a doctrine that was just the opposite: inclusive and universal. Open to any who believed. This idea of inclusiveness and universality was summed up nicely in Paul’s epistle to the Galatians when he said, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.”

Inner intent over outward appearances. Traditional honor is based on your public reputation, your “good name.” Christianity teaches that what the world thinks of you is not as important as what God thinks of you. Moreover, it emphasizes the importance of private intent and faith. For example, it’s not enough that you don’t have actual, physical sex with another man’s wife, you can’t even think about it. Because the chamber of a man’s mind and heart can only be seen by him, only the individual (and his God) can judge whether his intent and faith are adequate.

Pacifism. While countless wars have been fought “with the cross of Jesus going on before,” Christianity has also inspired many of its believers to devoted pacifism. Christ’s radical teaching to “turn the other cheek” and to “bless those that curse you” turned honor on its head; a Christian could find ample support in his scriptures that it was more honorable not to retaliate when insulted or attacked than to strike back. The example of Christ submitting willfully on the cross would inspire countless Christian martyrs to lay down their lives rather than fight back physically. For early Christians, the idea that a Christian could receive full military honors at death would have been an oxymoron.

Medieval Europe

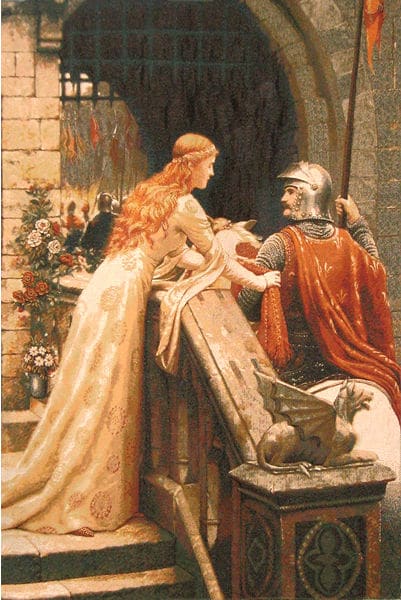

As Christianity spread and became the state religion for kingdoms and empires, the competing demands of traditional honor culture and faith created a moral and philosophical quandary. Traditional honor still had a primal hold on men, but elements of their new religion seemed to run completely counter to it. To bridge this seemingly insurmountable divide, Christian rulers during the Middle Ages “Christianized” traditional honor by developing the aristocratic Code of Chivalry. Chivalry wedded together primitive honor’s emphasis on public reputation, but added new moral virtues to the code that had to be kept to maintain that reputation, and thus keep the honor of one’s peers.

Traditional honor found a place among a pacifist Christian religion by marshaling honor’s historic emphasis on the qualities of strength and courage towards the defense of the “least of these” in Christ’s kingdom. Knights swore oaths to protect the weak and defenseless, particularly women. Honesty, purity, generosity, and mercifulness — virtues taught by the Gospels — were part of the knightly code. In keeping with Christ’s admonition to lay up your treasure in heaven and not in the world, some groups, like the Templars, even required their members to take a vow of poverty.

Beyond these small adaptations, medieval Christian chivalry was still primarily a traditional code of honor. Knights vowed to defend their own honor and the honor of their fellow knights. If his honor, or reputation, was besmirched by an equal, a knight had a duty to retaliate. For the medieval knight, might still made right. A knight could indeed be lacking in virtue, but as long as he could defeat the man who brought to light his moral defect in “single combat,” he remained a man of honor. The story of Sir Lancelot’s adulterous relationship with King Arthur’s wife, Guinevere, illustrates this; when the other knights discovered his sin, Lancelot insisted that his indiscretion didn’t exist because he was able to fight and best his accusers.

The Renaissance

Beginning in the 14th century in Italy, the Renaissance was a period of huge advances in art, science, and philosophy. Alongside these cultural evolutions, there was a transformation in the Western psyche that would eventually greatly weaken the classic concept of honor: the development of the idea of sincerity.

Sincerity demands that a person speak and act in accordance with his inner thoughts, feelings, and desires. It’s such a commonly lauded trait today (and has now morphed into an emphasis on “authenticity”), that it’s easy to think the concept has been around forever. But prior to the 17th century, people didn’t focus on having an inner life as we understand it today – in which you atomize and analyze all your feelings, emotions, and motivations. So as Renaissance men began to plumb the contents of their minds and hearts, they ran into a new contradiction between this inner life and traditional honor — which often requires an individual to place loyalty to the group first, and to speak and act in a way that contradicts his personal thoughts, feelings, and desires. Because traditional honor depends on the opinion of others, it doesn’t care if you feel like a hypocrite when following the code. So long as your outward appearances conform to the honor group’s code of honor, you maintain your honor. To show respect that was contrary to true beliefs and to receive such respect, however, didn’t fit in well with Renaissance values.

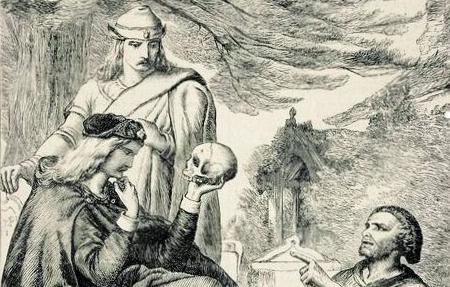

For this reason, Renaissance writers and thinkers began to question this aspect of honor and advocate for sincerity as the true ideal. Shakespeare was a harsh critic of traditional honor and a strong proponent for sincerity in his plays. In many of his works, the characters choose being true to oneself rather than submitting to their tribe’s code of honor. See Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet.

The new societal demands for sincerity during the Renaissance began a rapid shift in how societies perceived honorable people. An honor based solely on public reputation — especially if it demanded dueling or other extreme acts to keep one’s group’s high regard — didn’t seem all that desirable. It wasn’t enough that you acted truthful and others thought of you as honest, to be honorable, you actually had to be truthful to the core of your being. Honoring your parents with your outward behavior was no longer enough; you had to honor your parents in your heart.

The Enlightenment

The Enlightenment’s focus on tolerance and egalitarianism further diminished traditional honor – which at its core is inherently intolerant and anti-egalitarian. If you live up to the group’s honor code, you’re given rights and privileges; if you don’t, you’re shamed and seen as inferior. You don’t gain respect and praise simply by existing – your honor must be earned by your keeping, and excelling, of the group’s code. But Enlightenment thinkers began to forward the idea that all people had certain inalienable rights that they were born with and which could not be taken away. They also revitalized the ancient Greek ideal of democracy as a superior form of justice to the rewards and punishments meted out by the eye-for-an-eye concept of honor.

The Romantic Period

While Enlightenment philosophy eroded the concept of traditional, public honor, another group of 18th and 19th century thinkers, the Romantics, took up the baton of sincerity passed from the Renaissance and advocated for a new type of honor that was based on personal integrity. The Romantics, led by French writer and philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, believed that the individual and his desires should come before the group’s needs. Rousseau argued that honor based on the opinion of others (amour propre) was inferior to an honor based on what the individual thought of himself (amour de soi). For Rousseau and the Romantics, honor should be individual, internal, and private; not social, external, and public.

To justify this new definition of honor, Rousseau and his fellow Romantics fashioned a theory of human development that sentimentalized solitude. Before man formed tribes and groups, he lived independently in a state of nature, concerned only for his own happiness and well-being. It wasn’t until the Fall of Adam and Eve that man gathered in tribes and began to be concerned about what other fellows thought of him. This theory, of course, has been proven false by anthropologists. Mankind, like their primate cousins, have always been social animals and have always been concerned about their place in the group.

Despite being wrong about the history of human development, Rousseau and the Romantics created a legacy that lionized the importance of the individual, a drumbeat which intensified many times over in the 20th century, and would ultimately be one of the biggest nails in the coffin of traditional honor.

Despite the challenges created by the Enlightenment and Romanticism, traditional honor still had a strong hold on Western society in the 18th and 19th centuries. Aristocratic gentlemen continued to challenge each other to duels when they felt their honor, or reputation, had been impugned, even though the practice was illegal in most Western countries by then. Young soldiers, who had grown up reading epic poems and tales of battlefield glory, went to war hoping to capture that sense of honor that Homer and others wrote of. It would take the trenches of WWI to cool these deep reserves of martial fervor.

Conclusion, or Is Honor Making You Feel Kinda Uncomfortable Right Now?

As we can see, the transformation of honor from a public to private concept isn’t a recent phenomenon. The groundwork was actually laid at the beginnings of Western civilization. Ideals such as the rule of law, democracy, personal sincerity, egalitarianism and individualism fostered an environment antithetical to traditional honor. However, it wouldn’t be until the 20th century that honor would complete its transformation from meaning “having a public reputation worthy of respect and admiration” to simply meaning “being true to one’s personal ideals.”

As I said in the first post in this series, many people give a lot of lip service to honor, but don’t really know what it means, at least historically. Once they do learn more about it, they may begin to feel like it’s not such a good thing after all. Certainly, many of the seeds of the dissolution of honor, talked about here and next time, have become unquestioned Truths in our modern culture, and probably resonated more with you as you read than the idea of honor itself! But if you’ll stick with me, after this history, I’ll come back to explain that while personal, individual honor is a laudatory value, classic honor can also be a powerful and positive moral force as well.

Manly Honor Series:

Part I: What is Honor?

Part II: The Decline of Traditional Honor in the West, Ancient Greece to the Romantic Period

Part III: The Victorian Era and the Development of the Stoic-Christian Code of Honor

Part IV: The Gentlemen and the Roughs: The Collision of Two Honor Codes in the American North

Part V: Honor in the American South

Part VI: The Decline of Traditional Honor in the West in the 20th Century

Part VII: How and Why to Revive Manly Honor in the Twenty-First Century

Podcast: The Gentlemen and the Roughs with Dr. Lorien Foote

_________________

Sources:

Honor by Frank Henderson Stewart

What Is Honor: A Question of Moral Imperatives by Alexander Welsh

Honor: A History by James Bowman

Tags: Honor