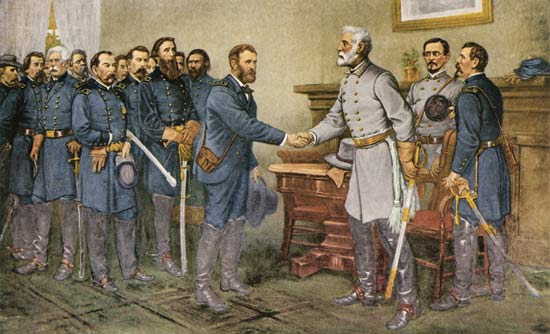

“I cannot describe it. I cannot give you any idea of the kindness, and generosity, and magnanimity of those men. When I think of it, it brings tears into my eyes.†-Charles Marshall, Aide de Camp to General Robert E. Lee

General Lee was wearing a new dress uniform, complete with a red sash and exquisite gold studded sword. Grant, who had not expected the surrender to happen so quickly, was in rough field garb, speckled with mud from riding to the McLean House. When Lee made the decision to surrender, he had said, “there is nothing left me but to go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths.” But not a trace of his anguish could be seen as the two men sat across from each other as the Civil War drew to a close. Grant reflected on that meeting:

“What General Lee’s feelings were I do not know. As he was a man of much dignity, with an impassible face, it was impossible to say whether he felt inwardly glad that the end had finally come, or felt sad over the result, and was too manly to show it. Whatever his feelings, they were entirely concealed from my observation; but my own feelings, which had been quite jubilant on the receipt of his letter, were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing over the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered much for a cause.â€

The men conversed genially for a time before getting down to business. Grant had no desire to add to the humiliation of the man who was 16 years his senior. He did not take Lee’s sword, allowed the Confederate officers to retain their sidearms, the soldiers to keep their horses and mules for spring planting on their farms, and all the Confederate army to return to their homes free men, if they pledged never again to take up arms against the Union. He also offered to give 25,000 rations to Lee’s starving soldiers.

The two generals parted cordially after their meeting. As Lee mounted his horse, Grant doffed his hat in respect, and his officers followed suit. Lee tipped his hat in return and rode off.

4 years. 625,000 deaths. And yet one man was able to accept defeat with dignity. And the other was able to claim victory with grace.

Grant and Lee were examples of true gentleman. And yet how often do we struggle with doing likewise in the comparably small losses and wins of our lives? How often do we fall into the trap of being the angry sore loser or the smug victor?

In this two part series, we will first look at how to lose with dignity. We will then explore how to celebrate with grace.

How to Lose with Dignity

Accept responsibility for the loss.

A boy blames everyone and everything but himself when he loses—the refs made bad calls, the teacher had it out for him, somebody else must have cheated. A man takes responsibility for what happened.

Bow out gracefully.

No one respects the man who’s still howling for another recount even after the votes have been fairly tallied or the man who’s still pleading to go double or nothing once he’s gotten into a hole. Once you’ve lost, bow out with your dignity intact.

When General Lee realized he had no choice but to surrender and informed his officers of his decision, one lamented, “O General, what will history say of the surrender of the army in the field?”

Lee answered:

“Yes, I know, they will say hard things of us; they will not understand how we were overwhelmed by numbers; but that is not the question, Colonel; the question is, is it right to surrender this army? If it is right, then I will take all the responsibility.”

Acknowledge the winner.

At the conclusion of the 2010 Superbowl, Peyton Manning moped off the field without shaking the hand of opposing quarterback Drew Brees and those of the victorious Saints.

Some said this was not unsportmanslike—that Manning was simply disgusted with the loss and should be able to openly show that disgust (the “do whatever you feel like!†argument). But a failure to acknowledge the victory of your fellow competitor shows a lack of respect for him; a man can be your rival, but you can still admire his courage and his fight, and the fact that on this day, he fought harder. Sulking away also shows a lack of discipline on your part—you are so overwhelmed with anger and grief at your loss that you cannot think of anything else but your own pity. Being able to control your feelings in that moment is the mark of strength and self-control, not to mention perspective.

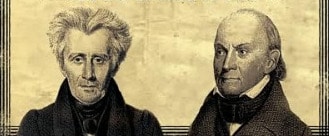

The presidential election of 1824 was a particularly bitter contest between Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams. Jackson had won the popular vote. But without a majority from the electoral college, the decision was thrown to the House, which chose Adams to be the next president. On the night he lost the election, Jackson attended a party at the White House where he came face to face with his rival. The moment was tense as the two men stared at one another. With his wife on his arm, it was Jackson who made the first move, extending his hand to the president-elect and cheerfully inquiring, “How do you do, Mr. Adams? I give you my left hand, for the right, as you see, is devoted to the fair. I hope you are very well, sir.†Answering with what an eyewitness recalled as “chilling coldness,” Adams responded. “Very well, sir; I hope General Jackson is well.†A party guest was struck by the irony of the exchange: “It was curious to see the western planter, the Indian fighter, the stern soldier, who had written his country’s glory in the blood of the enemy at New Orleans, genial and gracious in the midst of a court, while the old courtier and diplomat was stiff, rigid, cold as a statue!â€

Of course if your rival is so despicable that he does not warrant even an iota of respect, then you need not give him the respect of your acknowledgement. But be absolutely sure of that–in the heat of the moment you’re apt to think he won through nefarious means, only to realize later, once your anger has cooled, that he bested you fair and square. This goes for contesting the results as well–unless you’re pretty sure that your case can be proven, it’s best to be quiet; causing a row is apt to simply make you look like a petty, sore loser, hurting your reputation further.

And in some cases, even support the winner.

You’ve been putting in overtime at work. Doing the crappy jobs nobody else wants. Kissing butt and taking names. But when an upper-level position opens up, you get passed over for a new hire. You’re livid. You think about quitting but don’t really want to. So you stay, but how will you treat the new hire? Will you rejoice in his foibles as he learns the ropes? Will you seek to sabotage his success? Or will you put aside your bruised ego for the good of the team?

In 1940, England had lost faith in Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and his appeasement policies. He was forced to step down, and Winston Churchill took his place. In the late 1930s, the two men had been rivals; Chamberlain was the admired up and comer and Churchill was the political pariah. Both had fervently desired to be Prime Minister, and while Chamberlain had achieved the goal first, now he was out of the job and his rival was in. But what many don’t realize is that Churchill’s position was tenuous as first; there were those in Parliament who did not trust this man who had for so long been known as a reckless adventurer. It was Chamberlain who reassured the ranks of the Conservative Party and brought them into line behind Churchill, Chamberlain who accepted a position in Churchill’s war cabinet, chaired it during Churchill’s frequent absences, and administrated domestic affairs, and Chamberlain who helped persuade Churchill not to negotiate with Germany and to fight on. The sharp turn in Chamberlain’s fortune greatly depressed him, but his fellow cabinet members noted that he never showed any animosity towards them and always worked as hard as possible. It is thought that if this “loser” had not swallowed his pride and supported Churchill, the British Bulldog might not have lasted in office, and history could have turned out quite differently.

Learn from the loss and move on.

Some men manage to put on a dignified face immediately after a loss, but later proceed to question the victory of their rival—“He caught a lucky break,†“I don’t think he really did the project himself.†Instead, maintain your dignity and move on.

As we discussed earlier this week, losses and failures can be used as lessons and building blocks for getting better. Instead of using your energy to continually stew over the past and bad mouth your rival, focus on preparing for the next challenge, the next contest. Figure out why you lost. Find out what your competitor did differently. Ask your boss for honest feedback on why you were passed over for the promotion. And if a re-match is not possible or desirable, then get on with your life and fill it with new pursuits.

Do you have stories from your own life or from history of men losing with dignity? Share them with us in the comments!