On the fourth day of the voyage, he woke up early and relaxed in the top bunk of his cabin. Looking through a porthole positioned near his pillow, he could see over the deck, and out into the ocean. As he languidly gazed at the Mediterranean, and watched the sun begin to peek over the horizon, he suddenly saw the blur of a naked man rush by the glass. Startled and perplexed, he wondered if the figure had been some kind of apparition, and stuck his head out the porthole to get a better view.

The deck seemed quiet and empty, making Dahl feel he had perhaps being seeing things after all. But when a short, stocky, mustachioed figure rounded a corner, and once more came bounding by, it became clear he was not a ghost at all, but Major Griffiths, a fellow passenger of mature age.

With his flesh flapping and his slight pot belly jiggling as he ran along, Griffiths enthusiastically called out to Dahl:

“Come along my boy! Come and join me in a canter! Blow some sea air into your lungs! Get yourself in trim! Shake off the flab!â€

Dahl, who was quite taken aback by the sight, couldn’t manage to formulate a response to this surprising entreaty. As he relates in his memoir — Going Solo — he was simply left to shake his head and reflect on his conflicting feelings:

“I smiled weakly at the Major as he went prancing by, but I didn’t pull back. I wanted to see him again. There was something rather admirable about the way he was galloping round and round the deck with no clothes on at all, something wonderfully innocent and unembarrassed and cheerful and friendly. And here was I, a bundle of youthful self-consciousness, gaping at him through the porthole and disapproving quite strongly of what he was doing. But I was also envying him. I was actually jealous of his total don’t-give-a-damn attitude, and I wished like mad that I myself had the guts to go out there and do the same thing. I wanted to be like him. I longed to be able to fling off my pajamas and go scampering around the deck in the altogether and to hell with anyone who happened to see me. But not in a million years could I have done it.â€

The site of a naked man sauntering around a ship initially provoked Dahl to shudder with disapproval. But when he dug down into his feelings, he realized that his critical judgement really masked feelings of jealousy.

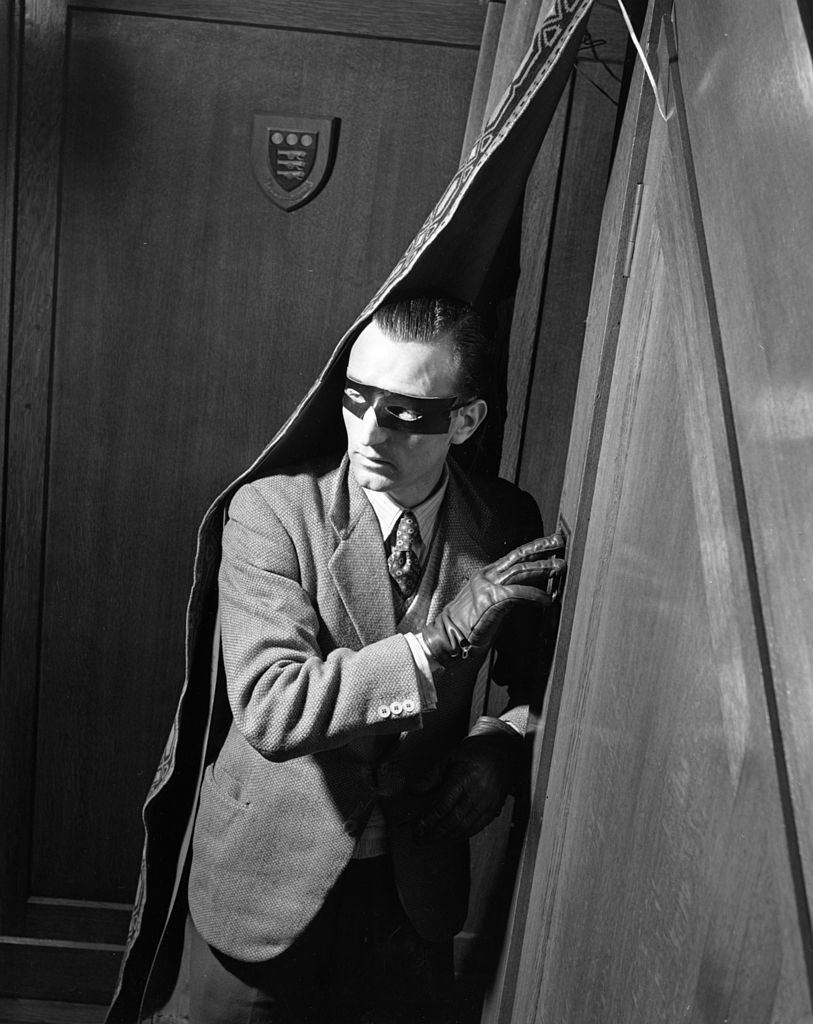

That’s the insidious thing about the specter of the green-eyed monster: it often wears various disguises that make it hard to recognize for what it is. We think our thoughts and behaviors are motivated by one thing, when it’s really envy that’s got the reins.

Today we’ll talk about a few of the guises jealously takes. Learning to identify them contributes to healthy self-awareness and can prevent us from doing and saying things that may ultimately be detrimental to our relationships, progress, and happiness.

3 Disguises of Jealously

“Repent!â€

I knew a couple of guys in college who were best friends and fairly devout in their faith. One was more attractive and got more dates than the other fellow, who had never even kissed a girl.

The former landed a steady girlfriend who he spent a fair amount of time making out with. Nothing at all scandalous, by most people’s standards.

But his friend saw fit to call him to repentance. Said he was disappointed, and that he thought the smoocher wasn’t living uprightly and ought to court his lady more purely.

A year later, the chastiser finally got himself a girlfriend. They started making out on the second date, and on every date thereafter. His untested principles, which he had felt so sure of in the abstract, rapidly changed once his position changed — once he had the opportunity to experience a situation firsthand that he had previously only deliberated on hypothetically.

He later realized that the self-righteousness he had felt about his friend’s behavior had really been a manifestation of his jealousy, rather than his conviction. He wished he had a girlfriend himself, but by engaging in a holy crusade, rather than confronting that fact, he was able to not only avoid feeling inferior to his friend, but could in fact feel superior to him.

Of course, this certainly doesn’t mean that every religious or moral principle a man upholds is really underlain by jealously. Nor does it mean that if you do feel jealous of someone breaking a value you’re committed to, it isn’t a right principle, and you should feel free to break it as well; you could feel a pang of envy that a friend gets to play the field after dumping his wife, for example, but that doesn’t mean you should follow suit.

It is simply wise to examine your feelings of personal righteousness to be sure that your standards haven’t been adopted and/or stretched beyond the mark for reasons you think are of born of piety, but are in fact fueled by envy.

“I hate that guy.â€

Is there someone that bothers the crap out of you? Maybe it’s a public figure, a writer, musician, or pundit. Maybe it’s just a former colleague or friend, a business rival, or an acquaintance you critically watch from afar.

Maybe you kind of hate them because they’re out and out a contemptible person, who says dumb things and has objectively done you and others wrong.

But it’s also worth looking under the hood of those acrimonious feelings. Sometimes, even when the person is a d-bag in a hundred different ways, in a least one way, you envy them. They’ve got something you want. They took an idea you kept in your head, and acted on it first. They’re doing something better than you are. It’s this envy that, if it hasn’t caused your dislike for them, has significantly deepened it.

This jealously disguise particularly crops up when it comes to business competitors.

Maybe there’s some guy who’s operating in the same space as you. Maybe there’s some area where he’s beating you. Rather than acknowledging that fact, though, you just focus on all the things you don’t like about your rival, all the ways your contempt for him is justified. Any anxiety you might be feeling over his maneuvers in the market are subsumed when you say, “I hate that guy.â€

While the relief offered by contempt may be sweet, temporarily, failing to diagnose the real cause of your resentment deprives you of the opportunity of candidly assessing a weakness, and working to get stronger in the long-term.

If someone’s got something you want, rather than ignoring this desire by blanketing it in all the things he does wrong, hone in on it, and figure out how to achieve it yourself.

“I don’t want it anyway.â€

When there’s a gap between how you’d like to see your life and how it really is, between your ideals and your behavior, between what you want and what you have, you experience cognitive dissonance.

This dissonance can be alleviated in one of two ways.

You can move your behavior to be closer in line with your goals. You can work to close the gap between how you’d like your life to be, and how it is.

Or, you can eliminate the distance between your ideal and your reality, by eliminating the ideal. You can decide that some goal you used to desire is stupid, pointless, not worth the time after all. This is the classic dynamic of sour grapes: “I can’t get this thing? I don’t want it anyway.â€

The trouble with option #2, is that it’s very difficult to get rid of a deep desire. To keep it at bay, you’ve got to constantly assail it and tear it down. Taking a nuanced view of the merits of the goal is out of the question; you must view it as wholly bad and entirely stupid to pursue.

You’d really like to find a girl to settle down with. But those you’ve approached so far haven’t reciprocated your advances. So, you decide that all women are untrustworthy, and that marriage is a stupid, outdated institution that only a fool would commit to.

You’d like to be a part of a college fraternity. But they all turn you down (or, you imagine that they would, and so don’t even try to pledge at all). So, you decide that those who belong to fraternities are all a bunch of dumb, alcohol-guzzling, coed-raping bros.

You weren’t born with a particularly masculine physique or disposition (like, say, our 26th president), but there’s a part of you that’d like to feel strong, confident, virile. Since it doesn’t seem possible, however, you decide that “manhood†is a culturally-relative concept that doesn’t really exist and that thinking about manliness is only for insecure, backwards-looking misogynists who need to redefine old concepts of masculinity for the new age.

Now, is it possible to come to the kinds of conclusions reached by these hypothetical gentlemen through honest examination, analysis, and conviction? Of course.

It’s just that sometimes, yes, sometimes such beliefs have in fact been fueled by jealousy — by sour grapes. All the vigorous efforts one engages in to tear something down have really been born from the feeling of being barred entry.

Unfortunately, the amount of rancor that must be engaged in to keep this acknowledgement from reaching one’s consciousness tends to canker the soul, and create a hobby horse that makes a man one-sided in his interests and personality. The denial of a desire that has only been submerged and hasn’t really gone away, tends towards creating an unhappiness that is hard to shake, because its real root is difficult to trace.

Better it would be, if a goal is seemingly blocked, to try a different strategy in attaining it, to pursue an alternative outlet to the same end — to move as close as you can to a desire within one’s limitations, working to make the most of what you got.

Lifting the Mask of Jealously

We often think we will know when we are feeling jealous; that it is as easily recognized an emotion as sadness or joy. But in fact, the green-eyed monster often sneaks into our lives in a variety of subtle disguises — masks that make us believe that rather than someone else having something we want, we are the superior ones.

Jealously need not be a wholly bad thing; it can act more like a symptom that points to some underlying weakness or unacknowledged desire we ought to address. But in order for jealousy to motivate us in a positive direction, we must recognize it when it arises, no matter what form it takes.