Scroll through some young guy’s Tumblr or Instagram feed and you’re bound to find a picture of a menacing-looking wolf with blood around its chops or a lone wolf howling at the moon. Superimposed on this image is invariably a quote in big bold lettering — some kind of edgy, muscular platitude about ignoring your haters, striking out on your own, and dominating everyone in sight.

You know, being a straight up alpha wolf.

The idea of there being alpha (and beta) wolves originated from Rudolph Schenkel of the University of Basel in Switzerland, who studied a pack of wolves living at a zoo in the 1940s. Schenkel observed that the wolves competed for status within their own sex, and that from these rivalries emerged a kind of “alpha pair†— a “lead wolf†that was the top male dog, and a “bitch†that was the top female dog.

Then in 1970, American scientist L. David Mech wrote a book called The Wolf, which expanded on Schenkel’s research and popularized the idea of alpha and beta wolves and the leader/subordinate social dynamic of wolf packs.

Both researchers described this dynamic as a competition for rank, with alphas being those who were domineering, aggressive, and violent, and used these qualities to fight off rivals to become the supreme leader of the pack.

Popular culture soon took this conception of the alpha wolf, along with the whole alpha vs beta distinction, and applied it to humans — especially men. Hence, the idea that to be an alpha male, you’ve got to take no prisoners, f*** s*** up each and every day, take what’s yours, and never say sorry.

There’s just one problem with this idea.

The research it’s based on turned out to be hugely flawed.

Below, we’ll explore the myth and reality of the alpha wolf. As we’ll see, looking to wolves for inspiration for human conduct can actually be useful and inspiring, but only if you’ve got a correct conception for what that behavior consists of. Here’s what it really means to be alpha like the wolf.

The Myth and Reality of the Alpha Wolf

For most of the 20th century, researchers believed that gray wolf packs formed each winter among independent and unrelated wolves that lived near each other. They had reached this conclusion from observing groups of wolves that had been taken from various zoos and thrown together in captivity.

Under these circumstances, researchers observed that wolves would organize the pack hierarchy based on physical aggression and dominance. The alpha male wolf, indeed, was the wolf that kicked ass and took names.

But then some researchers decided they should actually try to observe how pack formation happens in the wild.

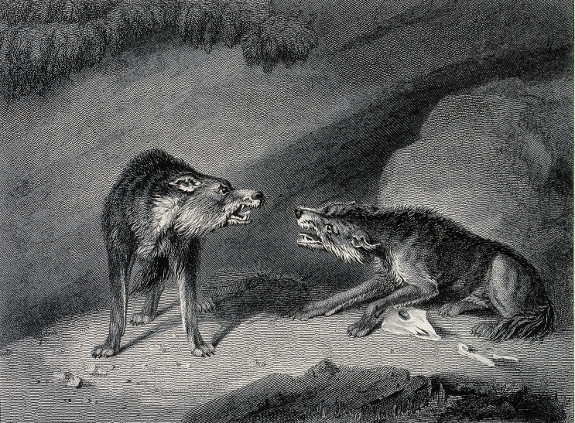

Based on their studies on confined wolves, they thought they were going to see this:

But were instead surprised to see this:

Instead of forming packs of unrelated individuals, in which alphas compete to rise to the top, researchers discovered that wild wolf packs actually consist of little nuclear wolf families. Wolves are in fact a generally monogamous species, in which males and females pair off and mate for life. Together they form a pack that typically consists of 5-11 members — the mate pair plus their children, who stay with the pack until they’re about a year old, and then go off to secure their own mates and form their own packs.

The mate pair shares in the responsibility of leading their family and tending to their pups. In 21st century human terminology, they “co-parent.†And by virtue of being parents, and leading their “subordinate†children, the mates represent a pair of “alphas.†The alpha male, or papa wolf, sits at the top of the male hierarchy in the family and the alpha female, or mamma wolf, sits atop the female hierarchy in the family.

In other words, male alpha wolves don’t gain their status through aggression and the dominance of other males, but because the other wolves in the pack are his mate and kiddos. He’s the pack patriarch. The Pater Familias. Dear Old Dad.

And like any good family man, a male alpha wolf protects his family and treats them with kindness, generosity, and love.

After observing gray wolves in Yellowstone for more than twenty years, wolf researcher Richard McIntyre has rarely seen an alpha male wolf act aggressively towards his own pack. Instead, an alpha dad sticks around until his pups are fully matured. He hunts alone or with his mate and children to provide food for the family (and sometimes waits for them to get their fill before he digs in himself), roughhouses with his pups (and gets a kick out of letting them win), and even goes out of his way to tend to the runts of his pack.

This isn’t to say male alpha wolves are all cuddles and kisses. They’re of course fierce predators, and can take down large prey like moose and bison. And when his family is threatened by outside enemies and competitors, the alpha male will fiercely defend it — sometimes sacrificing his own life to save his mate and pups.

This also isn’t to say male wolves don’t sometimes engage in displays of social dominance. Mature male wolves do have dominance encounters with other male wolves – fathers will stand up to a stranger alpha, or sometimes show their own kids who’s boss, and an older wolf brother will demonstrate his superiority to his little wolf bro.

So an alpha wolf can indeed be violent and assertive when the situation calls for it. Yet for the most part, he leads not with noisy brashness and teeth-bared aggression, but steady strength, mettle, and heart; as McIntyre told another wolf researcher:

“The main characteristic of an alpha male wolf is a quiet confidence, quiet self-assurance. You know what you need to do; you know what’s best for your pack. You lead by example. You’re very comfortable with that. You have a calming effect.â€

After learning how wolves actually form packs, researchers like L. David Mech retracted their original theory of alpha wolves and now eschew terms like “alpha male†or “alpha female†altogether when describing wolf hierarchy, instead preferring to classify the leader wolves as “breeding males†and “breeding females.â€

Unfortunately, the old conception has stuck around, and many men today have a mistaken notion of what it means to harness your inner alpha wolf. The reality of being an alpha is truly much more multi-faceted, and even more inspiring.

Making the Wolf Your Totem Animal of Manhood

I love the idea of animal totems, or at least finding inspiration from animals on how a man should live his life. Animals can serve as powerful symbols to us humans. The symbols become all the more powerful and meaningful when we have a correct understanding of how the animal actually behaves.

The gray wolf’s proclivity to roam and its prowess as a predator has for thousands of years made it a powerful symbol of the warrior, and of the freedom, wildness, and ferocity of masculinity. But that’s just one side of the wolf, and one side of what it means to be a man.

Yes, alpha male wolves are wild, aggressive, and savage. But they’re also protective, nurturing, and tender.

So if you want to truly become alpha like a wolf, you’ll need to do more than become a beast in the gym, and strive to overcome your competitors. You’ll also need to become a committed and dedicated family man — a loving and protective father.

While I’ve always loved wolves and their wildness, after learning more about the nuances of their social dynamics, I’ve fallen in love with them even more. The wolf is a nearly perfect symbol of the ideal of masculinity that I’m trying to get across here at Art of Manliness. Like alpha wolves, I want to see men who tackle life’s adventure with their mates by their side, and lead their families with heart and strength. I want to see men who have the ability to marshal the hard tactical virtues of masculinity when needed against external threats, but temper that ferocity with softer virtues like compassion and gentleness, particularly towards those they love.

In short, the male alpha wolf is the totem animal of the Gentleman Barbarian.

So by all means, continue sharing your savage wolf memes on Instagram and Tumblr. Wolves are awesome. But know that gray wolves howl to assemble their mate and pups before and after a hunt, to warn them of danger, and to locate each other during a storm, when traversing unfamiliar territory, or when separated over a great distance. It’s the call not of the angry, antisocial lone wolf, but of a father who’s leading, guiding, and lovingly gathering his pack.