Around 4:30am early one August morning in 2005, five 20-somethings decided to go explore a cave nestled in the side of a Provo mountain. When they arrived at the largely unknown and hidden spot, one member of the group, having a bad feeling about the idea, decided to wait outside and wished his friends well as they climbed inside the cave’s rocky mouth.

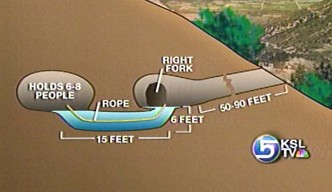

The cave’s unique features made it attractive to daring explorers: 30 yards inside its entrance, you encountered a hole that led into a completely underwater passageway. By swimming through the water-filled tunnel, you could enter another cavern in which you could pop your head up and breathe. A rope led from the entrance to the tunnel to the water-filled room so that people could pull themselves along and safely make their way through.

The young man who had decided to wait outside began to grow anxious as 15, and then 30, and finally 45 minutes passed without his friends reemerging. He called the police, and when rescuers entered the cave they found an awful scene: all four friends, two young men and two young women, had drowned. No one is quite sure what happened, but it seems the group had reached the second cavern safely, but died on the way back to the entrance: all were found facing the same direction in the water-filled passage. Those who had explored the cave previously told reporters that if you let go of the rope connecting the rooms, it was very easy to get disoriented inside the narrow tunnel. The tunnel extended past the exit hole and terminated in a dead end, making it possible to overshoot the opening. And as swimmers made their way through the passage, they would stir up sediment, muddying the normally clear water. Thus if you lost your grip on the rope, it was hard to find again, and panic and confusion could quickly set in.

I heard about this story when it happened seven years ago, and it made a deep impression on me and has come to my mind many times since. Obviously the haunting and truly tragic nature of the accident is part of what made it so indelible – it’s hard not to imagine what the doomed cavers last minutes were like.

But the main reason I have often found myself thinking about this accident has been the way in which from the very start it has seemed to me an arresting metaphor for our lives in general. How our values and goals — our very deepest beliefs — are very much like a rope that runs through our lives and to which we must hold fast, no matter how much our courage falters and distractions and harmful temptations cloud and muddy our vision.

Forgetfulness and Falling Chariots

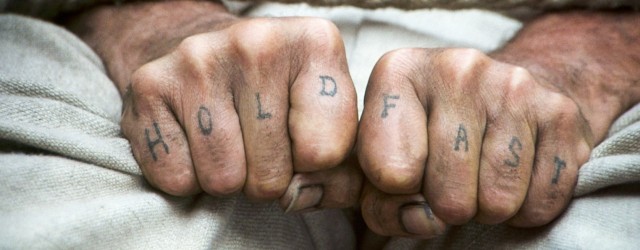

For the sailors of old, “hold fast†was both a noun (used interchangeably with “ropeâ€) or a verb meaning to grab the rope. Sailors would in fact often get the phrase tattooed on their hands – one letter on each finger – in order to remind themselves to stay vigilant in holding the lines, and as a magical protection: superstitious sailors believed the tattoo protected them from falling while climbing up the rigging.

A sailor’s grip on the rope could be loosened and undone by a bout of nerves, a strong wind, or a powerful wave. In a squall, a failure to hold fast could result in the man being swept overboard.

When piloting our metaphorical ship through life, the wind and waves are obviously figurative, but the result is the same: the loosening and dropping of our grip on the rope of our values and beliefs. So how do the figurative storms of life manage to get our grip to slip?

In the Phaedrus, Socrates (via Plato) offers us an answer to this question in the form of his famous Allegory of the Chariot.

In the parable, Plato compares his tripartite view of the soul or psyche to a chariot drawn by two winged horses. One of the horses is white, handsome, and noble and symbolizes spiritedness or the Greek concept of thumos. The other horse is dark, gangly, and rebellious and symbolizes human appetites. The Charioteer, or Reason, is tasked with corralling the disparate steeds into sync and guiding them on a flight into the heavens. Following a procession of gods in their chariots, the Charioteer seeks to soar past the highest ridge of heaven, in order to get a view of the “Forms†– the eternal essences of things like Truth, Beauty, Virtue, and Goodness. The gods have no problem piloting their chariots, but the human-souled Charioteers struggle with taming their dark horses, which try to pull the reins towards the earth. Thus the chariots bob up over the ridge, giving the Charioteers an inspiring view of the Forms, and then sink down again.

If a Charioteer loses this tug-o-war, his horses shed their wings and the chariot plummets to earth, where the soul becomes embodied in mortal flesh and must wait until the wings of his steeds regrow to once again begin a journey into the heavens.

Thus, Plato believed that the soul of every human on earth had once lived in a preexistence, where they had gotten a view of the Forms to a degree which varied according to how well they had guided their chariots. So for Plato, whenever you came to an understanding of some truth in this life, you weren’t discovering it for the first time, but were instead simply remembering what you had known in the preexistence. Therefore, he argued, the only man who is able to perpetually keep his wings is he who is:

“always, according to the measure of his abilities, clinging in recollection to those things in which God abides, and in beholding which He is what He is. And he who employs aright these memories is ever being initiated into perfect mysteries and alone becomes truly perfect.â€

By that same token, Plato argued that what brought a chariot to earth, and retarded the growth of the horses’ wings once there, was forgetfulness – forgetting one’s true nature and the Forms you had at one time beheld in the heavens:

“For as has been already said, every soul of man has in the way of nature beheld true being; this was the condition of her passing into the form of man. But all souls do not easily recall the things of the other world; they may have seen them for a short time only, or they may have been unfortunate in their earthly lot, and, having had their hearts turned to unrighteousness through some corrupting influence, they may have lost the memory of the holy things which once they saw.â€

Plato argued that the key to recollecting the truth we once knew and avoiding forgetfulness was rooted in our ability to recognize the shadows of divinity in our mortal lives. He believed that the Forms of heaven existed as hazy reflections on earth – “they are seen,†he said, as “through a glass dimly.†Whenever we encounter an earthly copy of heavenly truth, Plato said, we feel “rapt in amazement,†but most people are “ignorant of what this rapture means, because they do not clearly perceive.†What Plato meant is that people often have what feel like transcendent, soul-filling experiences when they see something beautiful and gain insight into a great truth, but they don’t realize that what they’re feeling is the reactivation of memories of things they already knew.

One way to look at it is to imagine that while in the preexistence, viewing the Forms embedded magnets of divinity within you. Once embodied as a mortal, a veil is drawn over any memory of that former world and the fact you have those magnets within. But whenever you encounter pieces of divine truth on earth, you feel yourself pulled and drawn to those things, although you may not know why. The more you can recognize that pull, and use it to seek out more divine magnets, the faster you can regrow your wings.

Seeing the Forms

While you can read Plato’s allegory literally as saying that humans experienced a preexistence prior to this earthly one, it can also symbolize the way we gain and forget truths across the course of our mortal lives. What then do the Forms represent in such an interpretation?

To see the “Forms†in your life is to have (and forgive this reference!) what Oprah might call an “ah-ha moment.†You feel as though you have drawn back the curtain on something once locked to you, and finally understand something about how things really are, or about who you are, why you’re here, and where you’re going. John Ubersax put it this way:

“Such an experience has a feeling-like quality, but also an intellectual component: an insight or clear recognition…that this is how things are meant to be; how obvious this all is, etc. This transcends ordinary experience, feeling, and reasoning. It is something you simultaneously see, feel, understand, experience, and participate in…This is our peeking temporarily into the realm ‘above the heavens.'”

Depending on your worldview, you may interpret such experiences as spiritual revelation, contemplative transcendence, or psychological flow and insight. Regardless of how you view it and its source, it imparts to you a truth about your purpose, direction, and/or identity.

You might think that such experiences would be absolutely unforgettable, and that the insights gained from them would forever after guide your life and choices. And yet how many of us, not long after uttering “ah-ha!†have been heard to exclaim: “This isn’t the man I want to be! This isn’t what I want out of life! How did I ever get so off track?!†It seems Plato was quite correct: it is very easy to forget the truths we’ve learned, lose our wings, and plummet to earth. The immediate aftershocks of a moment of insight quickly fade, and without a concerted effort to hold fast to those memories, forgetfulness loosens our grip on the rope of our lives.

Why this is so, and the prescient wisdom of a two-thousand-year-old philosopher, has been explained by modern science.

How We Remember and Why We Forget. Or, Why Becoming the Man You Want to Be Is Not Like Riding a Bicycle

Scientists have identified two main types of long-term memory: declarative (explicit), and nondeclarative (implicit). Nondeclarative memories are memories of how to do something, and are often related to motor skills like running or driving a car. You can’t describe these kinds of memories in words, which is why they’re termed “nondeclarative.†Declarative memories, on the other hand, are memories of what, where, when, and why — facts, people, experiences, ideas, concepts, and the relationships between them. You can “declare†or describe these memories to others.

You don’t have to consciously recall nondeclarative memories from your brain – when you pick up a toothbrush, you know what to do with it without thinking it through. It’s instinctive. And you can retain that instinct pretty much indefinitely without effort – hence the old saying about something being “like riding a bicycle.â€

Some men assume that becoming the man they want to be is like riding that proverbial bicycle. Once they have experiences that give them an understanding of their beliefs, who they want to be, and what they want out of life, they figure they won’t have any problem living out those insights – that they’ll simply set their course and sail straight for their goals. “Alright, I figured out what to do. Now I’ll do it.†One and done.

But the memories of our insights into who we want to be and what we want to do in life are in fact declarative memories; while aspects of your behavior can become habitual, acting in accordance with your values never becomes fully automatic, as it involves the constant making of conscious, sometimes very difficult, decisions.

Unlike nondeclarative memories, declarative memories must be consciously recalled from your brain. And it is in this recollection process that we encounter problems with forgetfulness.

Scientists believe that in general, once a long-term memory is consolidated in the cortex, it is there permanently. When we forget something, we may feel the memory has disappeared, but the problem is not existence but access. It’s there — we just can’t locate it.

When memories are encoded for long-term storage, the different aspects of that memory – everything from your physical location, mood, and level of motivation, to the smell, temperature, and ambient sounds present at the time — are broken up and stored in various locations in the brain. A neural network connects these disparate elements. When you recall a memory, a circuit fires through the network and reassembles those memory pieces into a whole. What this means is that any of these different pieces of memory can act like an entryway or cue that triggers the recall of the entire memory. For example, a memory of a childhood Christmas may have been broken up into the feeling of the fire in the fireplace, the smell of your mom’s cookies, the sound of Bing Crosby’s “Christmas Song,†the sight of lights twinkling on the tree, and the reading of A Night Before Christmas. Experiencing any one of these components separately later in life may cause this network of memories to light up and the whole memory of your childhood Christmas to come rushing back.

The more cues that were present when you first encoded the memory, that are present when you try to recall it later, the easy the memory is to retrieve. Think of the difference between simply imagining your old elementary school, and stepping foot back inside it – the latter will cause many more, and much more vivid, memories to come flooding back to you.

Similarly, scientists recommend that when studying for a test, students replicate the testing conditions they’ll experience on exam day as closely as possible. As they study, the cues in their environment will be encoded along with the information they are learning. When it’s time for the test, seeing the same cues again will help unlock the information the memory of those cues is tied to.

Conversely, in the absence of any of the cues that were present when a memory was encoded, a memory can sometimes be impossible to recall at a later time. It’s like looking for a library book without knowing its call number; it’s somewhere on the shelves but you don’t know where to look. This is called cue-dependent forgetting.

Cue Your Memories of the Man You Want to Be

What we learn from an understanding of cue-dependent forgetting, is that if we want to remember something, we often need to re-experience the same cues that were present when we first formed the memory.

For example, have you ever gotten up from the couch to get something in the kitchen, only to get there and realize you couldn’t remember what you came for? What often works to jog your memory is to retrace your steps, and cue-dependent recall is the reason this is effective. By sitting back down on the couch, the cues that were present when you first formed the memory of what you needed to get will trigger your recall of what it was.

And now at last we return to what it takes to hold fast to our beliefs and values and vision for our lives. We live in a world that prizes the exciting, the new, the original — and the idea of repetition sound pretty boring and unsexy. For the “one and done” folks, once you experience something, it’s on to the next thing. They say things like, “Why go to church every Sunday? The priest says the same things every week.†Or “I never read personal development books. I already know all that stuff already.â€

But if you want to keep the important things you’ve learned at the forefront of your mind, where they can influence your decisions and keep you on track, you have to purposefully keep exposing yourself to the same cues that were around when you first learned those things.

So for example, while I sometimes don’t feel like going to church because, yes, we often do talk about the same things over and over, I find that when I do go, the sound of a familiar hymn or a phrase a speaker uses will activate a whole network of memories about my beliefs and how I want to live my life. And what I hear is of course never exactly the same as what I heard before, and I add these new twists into the neural network that mapped the old insight, expanding it. The result is that I leave feeling reinvigorated about how I want to live my life and refocused on what’s important to me. My grip on the rope of my faith, which had loosened during the week, tightens.

Similarly, while it’s true that most personal development articles or books say the same things I already know and have been said for thousands of years, I find that even when they don’t say anything earthshaking, reading them reactivates a network of insights I’ve gotten in the past (“Oh yeah! I remember that concept. I hadn’t thought about that in awhile.”), renewing my motivation to tackle my personal goals. And again, I add some slightly new angles to my old ideas. My grip on the rope of my personal development tightens.

Cue-dependent remembering works for many other important areas of our lives too. If you’re feeling burned out at work, it may be that with advancements in your position and changes in your responsibilities, you feel cut off from the things that used to make you love your job. Revisiting those old people/places/tasks, can help you remember why you decided on this career in the first place.

If your love for your wife has faded from the heady times when you first fell for each other, revisiting the kinds of things you used to do together back then can provide the missing cues that will dislodge those old feelings of love and affection.

Finally, there’s a bonus to using cues to rejog your memories. Every time you actively recall a memory, it strengthens its pathway in your brain, making it even easier to retrieve next time.

Conclusion

People often ask, “Whatever happened to common sense?†Part of the answer to that question is that cues, basically reminders, on how to conduct your life in an honorable way, used to be built into the fabric of the culture. These moral reminders were included in school curriculums, and in popular songs, movies, and books. And teachers, parents, and neighbors were happy to offer reminders on being a good person if you were getting off track. Thus, it was hard to go very long without a cue triggering a memory of how you were supposed to act.

These days, cues on living a virtuous life are virtually absent from school or popular culture. And there are thousands of other stimuli vying for your attention. What this means is that you can’t hope to accidentally bump into cues every day that will help you remember the things that are most important to you. Instead, you have to purposefully plan for your regular exposure to those cues. You do this by regularly reading your scriptures, or personal manifesto, or books on philosophy and development, and doing other things which continually pull up all your past feelings and insights into the man you want to be, bringing them to bear on your present challenges.

The longer you go between getting those reminders, the more forgetfulness sets in, and the looser your grip on the rope of your values, beliefs, and goals gets. And once you lose hold of the rope, the harder it is to find again – the easiest way to stay on track is to never get too far from it. On the path to becoming the man you want to be, you have to hold fast to the rope that leads the way, no matter how rocky the journey becomes. Remember, remember.