“Of all the talents bestowed upon men, none is so precious as the gift of oratory. He who enjoys it wields a power more durable than that of a great king. He is an independent force in the world. ” –Winston Churchill

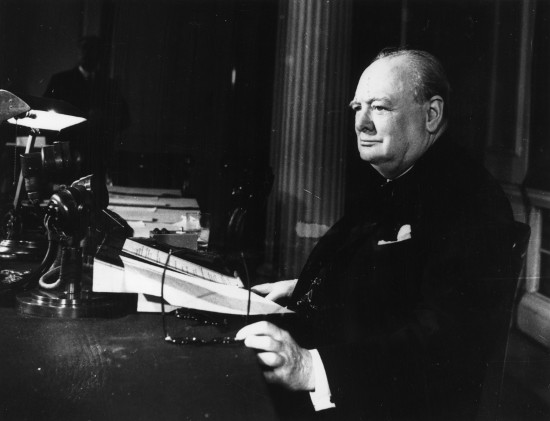

Ask anyone to name the greatest orators of all time, and Winston Churchill will assuredly be on, if not topping, the list.

We think of Churchill leading his fellow Englishmen through the darkest days of World War II, rallying them with calls to “fight on the beaches” and to offer their “blood, toil, tears, and sweat” to defeat the enemy. We think of him standing before the House of Commons, his bulldoggish countenance aglow, praising the RAF’s “finest hour” and unforgettably declaring that “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

Churchill’s talent for public speaking seems supernal — of a quality unattainable by the average man.

And yet his place in the pantheon of oration was far from fated. As a boy he stuttered and stammered, spoke with a lisp, and had a shy and timid temperament that hardly commanded the respect of his peers, much less a nation.

That he had an innate genius for words there can be no doubt. But he had to bring that latent power to life through tireless effort. As a young man, Winston made it his “only ambition to be master of the spoken word” and he honed his prowess like one does any other gift — through consistent nurture and practice.

When he first entered politics in his twenties, this youthful preparation earned his speeches generally good reviews. Yet he still had a ways to go; one observer thought his rhetoric seemed “scholarly and limp,” while another posited that “Mr. Churchill and oratory are not neighbours yet. Nor do I think it likely they ever will be.” Winston continued to sharpen his craft throughout his life, and from a weedy little boy, he grew into an orator whose entrance would hush an audience and prompt its members to lean forward in their chairs and towards their radios in anticipation of his words.

Few, if any of us, will ever become a speaker on par with Winston Churchill. Some people have “it†— that charismatic, irresistible quality in teaching and speaking that cannot be completely learned. But every man can become much better than he is, and magnify his own level of natural talent. While we may not be asked to address Parliament, we all are faced with speaking opportunities throughout our lives. Whether it’s running for student council president, making a presentation at work, having your voice heard at a city council meeting, or offering a eulogy, a knack for public speaking makes you a more persuasive and powerful man.

So the next time you’ve got to step in front of a podium, keep in mind the following advice from the English Bulldog himself. Some of his methodologies were uniquely suited for his temperament and time, but all are rich sources of guidance and inspiration:

1. Write Out What You Want to Say

Early in his political career, when he was 29 years old, Churchill was making a speech before the House of Commons in his usual manner. Up to that point, he had memorized each and every word of his speeches, and performed them without any notes. All had gone well, until this moment.

“And it rests with those who . . .†he begins to say. But he trails off, losing his train of thought.

“It rests with those who…†he repeats. Yet once more he fails at finishing the sentence, or pivoting to another.

For three long, agonizing minutes, Churchill gropes desperately for his next line and cannot for the life of him retrieve it. The House heckles him. His face turns red. Finally, he sits down, putting his head in his hands in utter dejection.

He would never make that mistake again. Henceforth, he wrote out his speeches word for word and had their text ever before him.

Improvising is truly a manly art, but so is admitting a weakness. Churchill had the humility to recognize that he didn’t have the knack for extemporaneous speaking. So he worked around it, so much so, that most listeners didn’t even realize that he was reading from notes.

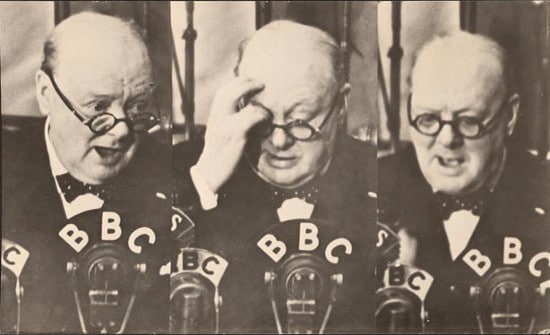

Churchill created this seeming spontaneity by infusing his speeches with all the energy, dynamism, and natural quality of an impromptu address. He rehearsed his remarks beforehand, so he only had to glance at his script occasionally. And his biographer William Manchester describes a technique he employed so that even these glances were scarcely noticeable:

“A consummate performer, he would rise, when recognized by the Speaker, with two pairs of glasses in his waistcoat. Perching the long-range pair on the end of his nose at such an angle that he could read his notes while giving the impression that he was looking directly at the House, he gave every appearance of speaking extemporaneously. If the occasion called for quoting a document, he produced his second pair and altered his voice and manner so effectively that even those who knew better believed that everything he said when not quoting was spontaneous.â€

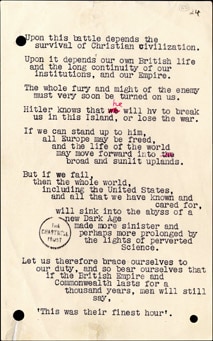

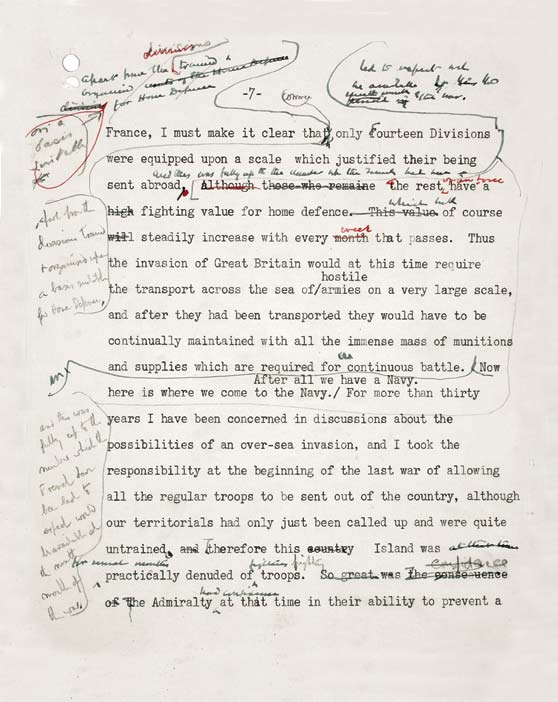

Final text of “finest hour” speech, in “psalm form.”

To aid in the flow of delivery, he would set the text of his speeches in what his staff called “psalm form†— a practice that may have been inspired by his love of the Old Testament. To these haiku-esque blocks, he would add notes for their delivery: where to pause and where to expect an ovation; which words and letters to emphasize; even where to appear to stumble a bit, grope for a word, and “correct†himself. Churchill knew that a flawless, robotic recital would put people to sleep, and that the more naturalistic a speech seemed, the more tuned in his audience would be.

Through preparation and practice, Churchill never again acted like the kind of orator he detested, who “before they get up, do not know what they are going to say; when they are speaking, do not know what they are saying; and when they have sat down, do not know what they have said.â€

2. Craft Your Speech With Great Care

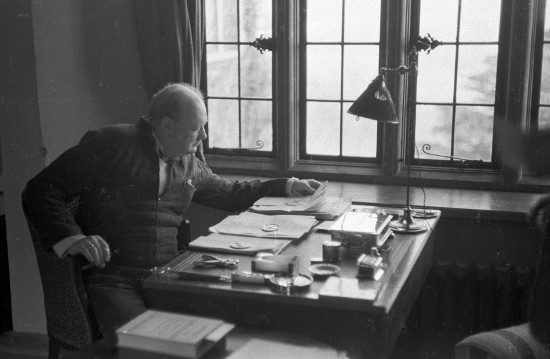

Churchill did not just scribble down the drafts of his speeches and call it good. A single 40-minute speech would take 6-8 hours for him to craft, and be subject to numerous revisions.

Churchill’s keen mind was always thinking of pithy phrases to insert into his speeches, and he came up with new lines in the spare moments between his daily duties. Even his famous witticisms and put-downs were rarely improvised on the spot; he had usually thought of the quip a ways back and filed it away to be retrieved and aired at just the right moment.

Once Churchill’s thoughts had marinated in his cranium for a sufficient amount of time, he dictated them to his secretaries, often while pacing the room in his dressing gown or soaking in one of his two daily baths.

An original draft of Churchill “Finest Hour” speech.

He would then pore over the first draft, studying each sentence and weighing whether the phrasing might be changed to add impact, or whether an adjective might be swapped for better effect. Multiple drafts, each sharper and tighter than the last, were produced.

In fact, Churchill’s revisions often continued until he was literally running out the door, late again to another appearance in Parliament.

3. Choose the Right Words

“Knowledge of a language is measured by the nice and exact appreciation of words. There is no more important element in the technique of rhetoric than the continual employment of the best possible word.†–WC

An average person’s vocabulary contains about 25,000 words.

Churchill’s has been estimated at 65,000.

Winston absorbed reams of words from his voracious appetite for books, which he had picked up as a young man. Though he struggled in most subjects in school, he found an interest, a gift, and a deep and abiding love in reading and writing the English language.

During his lifetime he would read over 5,000 books, ranging from literature and poetry to history and science fiction. His prodigious memory allowed him to remember whole passages from these texts, and recite them verbatim decades letter. His brain was like a fleshy version of Evernote — its folds containing endless notes on endless subjects. When he needed just the right anecdote, and just the right word to get his point across, he simply reached into a file and pulled out the needed pith.

He hardly viewed this mental warehouse as a dusty, musty card catalog either. Words thrilled him, fascinated him. He delighted in language’s musical, magical qualities; as Manchester writes, “Churchill’s feeling for the English tongue was sensual, almost erotic; when he coined a phrase he would suck it, rolling it around his palate to extract its full flavor.†Yet he also liked to use words with laser precision, and got great satisfaction from the feel of them “fitting and falling into their places like pennies in the slot.â€

Churchill felt that most often, the right word for a given groove was the most simple and homespun one you could find, arguing:

“The unreflecting often imagine that the effects of oratory are produced by the use of long words. The error of this idea will appear from what has been written. The shorter words of a language are usually the more ancient. Their meaning is more ingrained in the national character and they appeal with greater force.â€

Instead of saying “agreed to cooperate†he said “joined hands.†Instead of saying aeroplane and aerodrome (as was popular at the time), he said, “aircraft†and “airfield.†Others said “prefabricated,†he said “ready-made.†And when he first took office as prime minister, he changed the “Local Defense Volunteers†to the “Home Guard.â€

Can you imagine “blood, toil, tears, and sweat†rendered as “hemoglobin, exertion, lamentation, and perspiration�

Doesn’t have the same ring to it, does it?

Churchill not only disliked unnecessarily long and flowery words, but bureaucratic jargon and toothless euphemisms as well. Where other politicians referred to “the lower income group,†he said “the poorâ€; where they said “accommodation units,†he said “homes.â€

Though Churchill preferred shorter, punchier words, if such a one could not “fully express [his] thoughts and feelings†he didn’t hesitate to pull out a longer, meatier expression.

And if no existing word in the language properly fit his intended meaning, he wasn’t even opposed to coining a new one; “summit†(as a meeting), “Middle East,†and “iron curtain†all trace their etymologies to Churchill.

4. Infuse Your Speech With a Compelling and Musical Rhythm

“The great influence of sound on the human brain is well known. The sentences of the orator when he appeals to his art become long, rolling and sonorous. The peculiar balance of the phrases produces a cadence which resembles blank verse rather than prose.†–WC

Churchill not only carefully chose his words, but also intentionally crafted the effect and rhythm that came from putting those words, and then sentences, together. As a result, his speeches had a compelling cadence and rhythm — an almost musical quality.

In addition to an orator’s usual tricks — a well-timed pause, changes in tempo — Churchill employed various other devices to accomplish this effect.

His aim was always to link words together in a way that was pleasing to the ear. When he called Mussolini’s conduct “at once obsolete and reprehensible,†former prime minister Lloyd George criticized the phrase as meaningless. Churchill retorted, “Ah, the b’s in those words: ‘obsolete, reprehensible.’ You must pay attention to euphony!â€

Manchester notes that Churchill also enjoyed the effect of gathering “his adjectives in squads of four. Bernard Montgomery was ‘austere, severe, accomplished, tireless’; Joe Chamberlain was ‘lively, sparkling, insurgent, compulsive.’â€

Winston was famously a fan of repetition as well, and the way it could create a crescendo of emotional impact. See for example:

“You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: It is victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival.â€

And:

“We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall never surrender.â€

Churchill utilized chiasmus — a reversal in the order of words in two otherwise parallel phrases — in highly memorable ways too. In 1942, after the Allies won their first major victory of the war at El Alamein, he said: “Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.†A few more winning examples:

- “I am ready to meet my maker; whether my maker is ready for the great ordeal of meeting me is another question.â€

- “We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us.â€

- “I have taken more out of alcohol than alcohol has taken out of me.â€

On a more macro level, diplomat Harold Nicholson said that of all of Churchill’s devices, “the winning formula†and “the one that never fails†was Winston’s “combination of great flights of oratory with sudden swoops into the intimate and conversational.â€

In The Churchill Factor, author and mayor of London Boris Johnson, posits that Churchill’s “finest hour†speech offers perhaps the best example of this arresting combo. Winston begins with “Never in the field of human conflict…†— what Johnson calls “a pompous and typically Churchillian circumlocution for war.†From here he neatly segues into “has so much been owed by so many to so few†— a string, Johnson notes, of “short Anglo-Saxon zingers.â€

These masterful swoops from the lofty to the homespun are part of what made Churchill’s speeches so engaging; he spoke both to the country’s well-educated aristocrats as well as its salt of the earth laborers. His speeches could fire the emotional imagination and challenge the intellect by equal turns — there was truly something for everyone.

5. Build Your Argument Towards an Inescapable Conclusion

“The climax of oratory is reached by a rapid succession of waves of sound and vivid pictures. The audience is delighted by the changing scenes presented to their imagination. Their ear is tickled by the rhythm of the language. The enthusiasm rises. A series of facts is brought forward all pointing in a common direction. The end appears in view before it is reached. The crowd anticipates the conclusion and the last words fall amid a thunder of assent.†–WC

Churchill called the ideal oratorical flow outlined in the quote above the “accumulation of argument.â€

It begins by placing the most important point first.

Then the audience is swept along as you present different pieces of evidence, one after the other, smoothly segueing between them.

Sometimes the compiling of evidence merely consists of saying the same thing multiple times, in slightly different ways. “If you have an important point to make,†Churchill advised, “don’t try to be subtle or clever. Use a pile driver. Hit the point once. Then come back and hit it again. Then hit it a third time — a tremendous whack.â€

Finally, you reach the resounding, electrifying climax that leaves the audience with but one inescapable conclusion.

Case in point: the fraught war cabinet meetings of May 26-28, 1940. France had fallen. England’s position was perilous at best. Churchill had just assumed the prime ministership but his support was far from universal and his job security was tenuous. Italy began to make overtures, offering to help the British negotiate a peace with Hitler. Viscount Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, thought that given their precarious position, it would be prudent to enter into discussions.

Churchill was, of course, diametrically opposed to any such settlement, arguing that “nations which went down fighting rose again, but those which surrendered tamely were finished.”

The debate between Halifax and Churchill went on and on for many hours over many meetings. Finally, Churchill asked to speak with his “Outer Cabinet,†hoping that shoring up broader support for his position might decide the matter. He made his case to the 25-member board, and then concluded by saying:

“I have thought carefully in these last days whether it was part of my duty to consider entering into negotiations with That Man [Hitler]. But it was idle to think that, if we tried to make peace now, we should get better terms than if we fought it out. The Germans would demand our fleet — that would be called disarmament — our naval bases, and much else. We should become a slave state, though a British Government which would be Hitler’s puppet would be set up…And where should we be at the end of all that? On the other side we have immense reserves and advantages.

And I am convinced that every one of you would rise up and tear me down from my place if I were for one moment to contemplate parley or surrender. If this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.â€

Now, that’s a climax.

Twenty-five seasoned politicians erupted in cheers and shouts, jumping from their seats and slapping Churchill on the back. Winston had won the day. And the future of the world was changed forever.

6. Use Rich Imagery and Analogy

“The ambition of human beings to extend their knowledge favours the belief that the unknown is only an extension of the known: that the abstract and the concrete are ruled by similar principles: that the finite and the infinite are homogeneous. An apt analogy connects or appears to connect these distant spheres. It appeals to the everyday knowledge of the hearer and invites him to decide the problems that have baffled his powers of reason by the standard of the nursery and the heart…the influence exercised over the human mind by apt analogies is and has always been immense. Whether they translate an established truth into simple language or whether they adventurously aspire to reveal the unknown, they are among the most formidable weapons of the rhetorician. The effect upon the most cultivated audience is electrical.†–WC

A speech which consists only of dry facts and figures is neither engaging nor memorable. The human mind longs to have its imagination stirred, and readily latches onto pictures and comparisons.

An analogy can cut through the chaotic and confusing to offer a graspable towrope to understanding. A rich metaphor can often produce a true a-ha moment that removes the veil from one’s eyes and allows the listener to see something in a new way.

Churchill had a painter’s ability to create such imagery and metaphors in his speeches. “His words,†Manchester argues, “became more real than the scenes depicted, and more evocative than the sum of his grammatical strokes and rhetorical shadings.”

Churchill spoke evocatively of the “jaws of winter†and the desire to move into the “broad sunlit uplands†of a peaceful future. He called Germans “carnivorous sheep†and Hitler a “bloodthirsty guttersnipe.â€

His analogies could sometimes be witty; in regards to the growing Nazi threat he said: “A baboon in a forest is a matter of legitimate speculation; a baboon in a Zoo is an object of public curiosity; but a baboon in your wife’s bed is a cause of the gravest concern.â€

Yet for my money, Churchill’s most evocative analogy was one he offered during the 1930s, as Hitler began to seize power and annex territories. Troubling events did not often come one right after another; there would be lulls in-between, lulls in which the Führer declared he was satisfied and would not grab for any more land. These letups coaxed Europeans into complacency, and Churchill wished to snap them out of it:

“When you are drifting down the stream of Niagara, it may easily happen that from time to time you run into a reach of quite smooth water, or that a bend in the river or a change in the wind may make the roar of the falls seem far more distant. But†— here his voice dropped into a forceful, quiet tone — “your hazard and your preoccupation are in no way affected thereby.â€

7. Give Voice to People’s Latent Sentiments and Ideals

“The orator is the embodiment of the passions of the multitude.†–WC

Many have argued that Hitler and Churchill were two sides of the same coin: both were effective, charismatic, glory-hungry, power-seeking, vision-creating leaders. Both were also, of course, talented and compelling orators.

The difference, naturally, is that one used his abilities for good, and one for evil.

Hitler catalyzed peoples’ submerged prejudices and desire for status at the expense of others.

Churchill activated men and women’s noblest proclivities, presenting them with a vision of themselves as courageous heroes, standing as a last bulwark of democracy.

In both cases, these orators merely gave voice to the sentiments and drives already latent within their countrymen. That is why they were so very effective.

Manchester notes that Churchill spoke for his fellow Englishmen, not to them. He helped express convictions they already held themselves, but had trouble putting into words.

On receiving a compliment to this end, Churchill said:

“I was very glad that Mr. Attlee described my speeches in the war as expressing the will not only of Parliament but of the whole nation. Their will was resolute and remorseless and, as it proved, unconquerable. It fell to me to express it, and if I found the right words you must remember that I have always earned my living by my pen and by my tongue. It was a nation and race dwelling all round the globe that had the lion heart. I had the luck to be called upon to give the roar.â€

8. Be Sincere

“If we examine this strange being [the orator] by the light of history we shall discover that he is in character sympathetic, sentimental and earnest…Before he can inspire them with any emotion he must be swayed by it himself. When he would rouse their indignation his heart is filled with anger. Before he can move their tears his own must flow. To convince them he must himself believe.†–WC

During the first part of Churchill’s career, his speeches were effective and mechanically well-done, but lacked a certain something. They had their desired impact in the moment, but their effect wasn’t lasting. As the Liberal MP Edwin Montagu wrote in 1909: “Winston is not yet Prime Minister, and even if he were he carries no guns. He delights and tickles, he even enthuses the audience he addresses — but when he has gone, so also has the memory of what he has said.â€

While Churchill could go through the rhetorical motions on any given subject, and enjoyed seeing how well he could ace his delivery and rouse an audience, the problem was that he wasn’t always deeply invested in his message.

Regular political issues interested him, but at his essence, Churchill was a martial man, most inspired by the life-and-death stakes of battle. Thus, it would take an arena as epic as WWII for Winston to really hit his oratorical stride.

If there was anything Churchill could speak on with a depth of sincerity and true fervor, it was the heroism required of wartime. Its excitement and sorrow, danger and meaning, was not something he had to artificially force — he was moved by it at his core. In fact, when he dictated his speeches, his emotion was so raw and real, that sometimes he and his secretary would both be crying.

He also had the sense not to rely on the ability to conjure up the emotion of an event in its aftermath, but to be a journalist about his experiences — taking note of how certain things felt in the moment so he could later express it to others. For example, after visiting an RAF bunker during the Battle of Britain, Major General Hastings Ismay turned to him to make a comment. Churchill preempted the general, saying, “Don’t speak to me, I have never been so moved.†It was then that the famous line — “never has so much been owed by so many to so few†— came to him. It sounds so genuine, even 75 years later, because it was born of authentic, real-time emotion.

Churchill’s sincerity was also a product of his “skin in the game.†He detested euphemisms offered by those hunkered down in comfortable bunkers far from the front — platitudes contrived by those who had never seen action themselves. In Churchill, the English had a leader of a different sort — one who was right in the arena with them, who was not just calling for sacrifice but living it. They listened more readily because they knew that he was toiling day and night for their benefit; watching the bombs come in firsthand, despite the danger; and going out amongst the wreckage and ruins to personally buoy their spirits.

Churchill was not just a speaker, but a doer, and that made him the most effective kind of orator of all. Said one listener of his “we shall fight on the beaches†speech: “it sent shivers (not of fear) down my spine. I think one of the reasons why one is stirred by his Elizabethan phrases is that one feels the whole massive backing of power and resolve behind them, like a great fortress; they are never words for words’ sake.â€

_____________

Sources:

The Last Lion Trilogy by William Manchester

The Churchill Factor by Boris Johnson

“The Scaffolding of Rhetoric†by Winston Churchill

Tags: Speeches