In case you missed it: Read Part I of this short series.

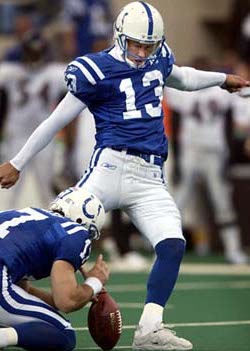

It’s the 2005-2006 NFL Playoffs. The Pittsburgh Steelers and the Indianapolis Colts have battled it out for four quarters. The Colts are down 21-18, and there are 18 seconds left in the game. The Colts’ kicker, Mike Vanderjagt, steps up to nail a 46-yard kick that can tie the game and send it into overtime. The Colts are confident in their man; having made 88% of his previous attempts, Vanderjagt is the most accurate field goal kicker in NFL history. His foot connects with the ball, and it launches into the air, soaring right, wide right, completely missing the uprights. The Colts’ season is over. And so is Vanderjagt’s NFL career; the Colts decline to re-sign him, and he is picked up and consequently dismissed by the Dallas Cowboys.

Vanderjagt had experience and incredible skill, but he choked at a crucial moment. What happened?

During the 2005 season, Vanderjagt began to lose his confidence. “I always approached every kick with the thought that if I miss, I’m out of the league,†he later reflected. Afraid of losing his livelihood, he started to over-analyze his kicks during practice, but that only led to more mistakes.

“I’m not smooth,†Vanderjagt said. And that’s the heart of what happened to him during that crucial game–because the key to being clutch is to keep your smoothness. And how do you do that? By not preventing your procedural memory from–ahem–kicking in.

What Is Procedural Memory?

Procedural memory guides the processes (often motor skills) that we do unconsciously. Situations where you might find yourself using your procedural memory in high pressure situations include making the free throw that wins a basketball game, sinking the putt that wins you the bet between your friends, or playing the guitar for a group of people when you’re put on the spot.

Why We Choke During Tasks That Require Our Procedural Memory

When you practice something over and over again, the knowledge of how to do that task gets burned into your unconscious and into your “muscle memory.” Your body can instinctively remember how it feels to do something right.

When you start to think too much about the task you’re trying to accomplish, you block the pathways to this muscle memory. Over-thinking things shuts off your instincts, which know what to do, from kicking in.

Let’s use playing the guitar as an example. You’ve practiced for years in your room, moving from the three guitar chords every man should know, to some really complicated sequences. You’ve developed serious chops and can lose yourself in killer solos, and your hands and fingers move and press and strum without you doing much thinking about it at all. But when you stand in front of an audience for open mic night, nervousness gets the better of you. You start thinking about how to place your fingers for the next note, and your playing falls apart. You’ve thwarted the power of your procedural memory by over-thinking it.

The Key to Being Clutch When Using Your Procedural Memory

To excel under pressure and be clutch with tasks that require procedural memory, you must distract yourself from the task at hand. Instead of over-thinking what you’re doing or are about to do, you must trust that the hours of training and practice you’ve put in before that moment won’t let you down.

Distract yourself. If you’re lining up for a golf putt, distract yourself from the mechanics of your putt by counting backwards or singing. Our guitarist above can close his eyes when he starts to feel nervous when playing in front of an audience (as an added bonus, scrunching his eyes shut will make the girls think he’s deep).

Develop a mantra. Sports psychologists often counsel their athletes to develop a mantra they can repeat when the pressure is on. Mantras are just another way to keep you from over-thinking what you’re doing in a high-pressure situation. Baseball Hall of Famer George Brett’s mantra when he was up at bat was “Try easier.” A basketball player could use a mantra like “Relaxed and smooth,” for when he steps up to the free throw line. When you’re on the putting green, use the immortal mantra of Chevy Chase in Caddyshack: “Be the ball.”

Focus on the target, not your mechanics. Another tactic you can use to avoid paralysis by analysis is to focus on your target, instead of your mechanics. For example, when you’re trying to bowl a strike, you don’t want to think about your approach, so you should focus and aim at an arrow on the lane instead. When firing a gun, focus on getting a clear sight, not on your trigger pull.

Don’t slow down. Remember how with tasks that require working memory you should slow down? Well, forget that bit of advice for tasks that require procedural memory. Studies show that the faster you get going, the better you do. Football coaches understand this and will often try to throw off opposing kickers by calling a time-out right before they kick the ball. This technique is called “icing the kicker.” The idea is that giving the kicker more time to think about the kick will increase his analysis and anxiety, thus blocking his procedural memory from guiding the ball through the uprights. If you’ve ever mountain biked, you’ve probably witnessed the truth in this. If you see an obstacle up ahead on the trail and cautiously slow down in anticipation, you will often awkwardly hit the obstacle and fall over. But, if you swallow your fear and keep up a quick pace, more often than not the bike will sail right over the obstacle.

High Pressure Tactics for Both Working and Procedural Memory Tasks

So we’ve talked about tactics tailored for situations that involve your working memory and for those that engage your procedural memory. But there are also things you can do that can help you no matter the high-pressure mission you’re trying to accomplish.

Practice tactical breathing. Tactical breathing was developed by Lt. Col. Dave Grossman. It’s a technique that soldiers and police officers use to quickly calm down and stay focused in high-pressure situations like firefights. Here’s how to do it:

- Slowly inhale a deep breath for 4 seconds.

- Hold the breath in for 4 seconds.

- Slowly exhale the breath out for 4 seconds.

- Hold the empty breath for 4 seconds.

- Repeat until your breathing is under control.

Simple. What’s hard is having the discipline to do this when you start feeling stressed out. Before delivering that big sales pitch or negotiating your new raise, take a few minutes to do some tactical breathing to clear your mind and keep yourself calm, cool, and collected.

Practice under pressure. Practice under the same conditions that you’ll face when you have to perform for real. While you can’t replicate the stress level of real-world situations in a practice setting, even training under mild stress can improve a person’s ability to thrive in clutch situations.

A great example of the power of practicing under pressure comes from Southern Utah University’s basketball team. Before coach Roger Reid arrived in 2007, the team ranked 217th in free throw percentage. By 2009, the team was ranked number one. What did Reid do to help his players thrive in the often high-pressure stakes of free-throw shooting?

During practice, Reid would randomly stop everything and bring his players to the free throw line. If the player made the shot, he got to take a breather. If he missed, he had to sprint around the court. By putting something on the line for failing to miss a practice free throw, Reid was able to help his players better handle game-on-the-line free throws.

If you’re preparing for a test, do your practice exams under the same time limit you’ll have on test day and without the use of study aids. If possible, practice in the same room in which you’ll be taking the actual test. If you’re preparing for a speech, practice in front of a friend or even a camera. Studies have shown that athletes or performers who practice in front of the watchful gaze of the lens perform better than those who practice in isolation.

Stay active and outwardly focused. In the book War, by Sebastian Junger (which I highly recommend), he shares an interesting study done on a Special Forces team during the Vietnam War. The team was stationed at an isolated base along the Cambodian border and knew there was a good chance of the base being completely overrun by a force of Vietcong. Surprisingly, researchers found that in contrast to the officers, the stress levels of the enlisted men actually dropped before an expected attack, and rose when the attack failed to materialize. Researchers offered this explanation: “The members of this Special Forces team…were action-oriented individuals who characteristically spent little time in introspection. Their response to any environmental threat was to engage in a furor of activity which rapidly dissipated the developing tension.” This activity included laying C-wire and mines around the base, which as Junger notes, “was something they knew how to do and were good at, and the very act of doing it calmed their nerves.”

When you’re facing a threat of a less deadly variety, take a cue from the men of the Special Forces; instead of sitting around navel-gazing, bouncing your leg up and down, and working yourself into a ball of nerves, keep yourself occupied with preparations. Read over your notes again, shine your shoes, take some practice shots…

Stay humble. Remember, “Pride goeth before a fall.” We’ve all seen examples where over-confidence in sports resulted in choking when the pressure was on (cough, Miami Heat, cough). Over-confidence can kill your performance because it keeps you from striving to improve. If you want to be clutch, you need to strengthen your skills and prepare every day for those high-pressure moments. Stay hungry and humble.

Listen to our podcast with Don Greene about performing under pressure:

Sources and Further Reading

Clutch: Why Some People Excel Under Pressure and Others Don’t by Paul Sullivan

Choke: What the Secrets of the Brain Reveal About Getting It Right When You Have To by Sian Beilock (I thought this was the better and most informative of the two)