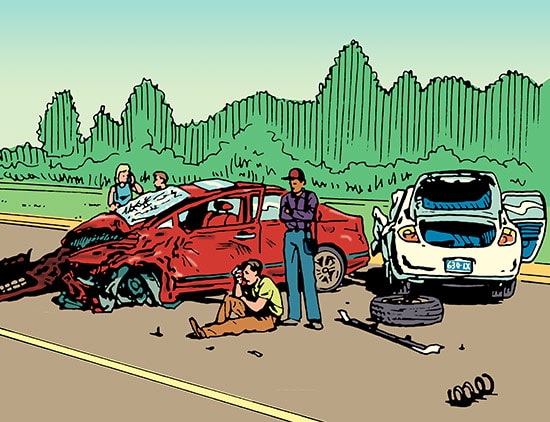

STOP: BEFORE YOU READ ON, STUDY THE PICTURE ABOVE FOR 60 SECONDS.

THEN, SCROLL DOWN AND SEE IF YOU CAN ANSWER THE FOLLOWING QUESTIONS:

- How many people total were involved in this accident?

- How many males and how many females?

- What color were the two cars?

- What objects were lying on the ground?

- What injury did the man on the ground seem to be suffering from?

- What was the license plate number of one of the cars?

How did you do on this little test? Not as well as you would have liked? Perhaps it’s time you strengthened your powers of observation and heightened your situational awareness.

Enhancing one’s observational abilities has numerous benefits: it helps you live more fully in the present, notice interesting and delightful phenomena you would have otherwise missed, seize opportunities that disappear as quickly as they arrive, and keep you and your loved ones safe.

Today we’re going to offer some games, tests, and exercises that will primarily center on that latter advantage: having the kind of situational awareness that can help you prevent and handle potentially dangerous and critical situations. But the benefits of practicing them will certainly carry over into all other aspects of your life as well.

Ready to start heightening your senses and building your powers of observation? Read on.

Situational Awareness and Your Senses

Strengthening your situational awareness involves making sure all of your senses are turned on and fully tuned into your environment. It seems like your mind and body do this automatically — aren’t you seeing, smelling, and hearing everything around you, all the time?

But when someone asks you something like, “What’s your license plate number?†and you draw a blank, you quickly realize that it’s possible to have looked at something hundreds of times without ever seeing it.

In fact, while our brain gives us the feeling that we’re taking in the whole picture of our environment from moment to moment, this is an illusion. We’re really only paying attention to some sets of stimuli, while ignoring others.

Thus, if you want to strengthen your situational awareness, you have to be truly intentional about it — you have to consciously think about utilizing and directing all your senses to a greater degree. You have to train for observation. And the first step in doing so, is getting reacquainted with the powers and pitfalls of your senses:

Sight

Seeing is what we typically think of when we think of observation, and it’s what we lean on the most to make sense of our world. Yet what our eyes take in is also not as accurate as our brains would have us believe. Eyewitness accounts of crimes are notoriously unreliable, and famous studies — like the one in which folks are asked to concentrate on people passing a basketball back and forth, and in so doing miss a man in a gorilla suit walking through the picture — show us that we can look right at something, without actually seeing it.

These blind spots are due to the fact that our eyes don’t operate like cameras that record scenes just as they unfold; rather, our brains take in a number of different shots, and then interpret and assemble them together to form a coherent picture. Left on autopilot, our brain ignores many things in our environment, deeming them unimportant in creating this image.

Nevertheless, sight is an incredibly vital part of our situational awareness arsenal — especially if we train ourselves to look for things we’d normally miss. Our eyes tell us if someone looks suspicious or if something is out of place in our hotel room (indicating someone’s been there in our absence); they spot peculiar features of a landscape to help us create a mental map to guide us home from a hike; they take footage of the exits in a building or of a crime that we can remember later.

Hearing

As sight-driven creatures, we take in a ton of information with our eyes (as much as a third of our brain’s processing power goes towards handling visual input), and most of us feel we’d rather lose our hearing than our sight.

But hearing is far more essential to keeping track of and understanding what’s going on around us than we realize — especially when it comes to staying safe. Our hearing is incredibly attuned to our surroundings and functions as our brain’s first response system, notifying us of things to pay attention to and fundamentally shaping our perception of what’s happening around us. As neuroscientist Seth Horowitz explains:

“You hear anywhere from twenty to one hundred times faster than you see so that everything that you perceive with your ears is coloring every other perception you have, and every conscious thought you have. Sound gets in so fast that it modifies all the other input and sets the stage for it.”

Our hearing is so fast because its circuitry isn’t as widely dispersed in the brain as the visual system is, and because it’s hooked into the brain’s most basic “primal†parts. Noises hit us right in the gut and trigger a visceral emotional response.

The quickness and sharpness of our hearing evolved from its survival advantage. At night, in dense forests, and underneath murky waters, our sight greatly diminishes or completely fails us, and we can’t see anything beyond our field of vision. But our ears can still pick up sensory input in darkness, around corners, and through water in order to build a mental picture of what’s going on.

Noises are nothing more than vibrations, and we’re completely surrounded by them every day. But just like with sight, your ears can be listening to tons of sounds in your environment, without your brain really hearing them; your antennae are always up, but they don’t always send a signal to pay attention. Such signals only register in your conscious awareness when they’re particularly salient (as in when you hear your name said at a busy party), or when they break the usual pattern/tone/rhythm that your brain expects (like when there’s a scream, crash, or explosion, or someone is talking in a strange/suspicious way).

We can tune into more sounds than we usually hear by “perking up†our ears, concentrating, and trying to distinguish and pull out noises we’re usually “ear-blind†to.

Smell

In comparison to our senses of sight and hearing, smell doesn’t get much attention and respect. It’s our oldest sense, and we tend to think of it moreso with animals than ourselves — like the wolf that can smell its prey almost 2 miles away.

While dogs indeed have a sense of smell that’s 10,000-100,00X more powerful than ours, the human sense of smell is nothing to, well, sniff at. Humans have the ability to detect one trillion distinct scents. And while our other senses have to be processed by numerous synapses before reaching the amygdala and hippocampus and eliciting a reaction, smell connects with the brain directly, and thus gets deeply attached to our emotions and long-term memories. This is why catching a whiff of something from long ago can instantly transport you back in time.

These ingrained, smell-induced memories serve the same kind of survival purpose in humans as they do in animals — to identify family and mates, find food, and be alerted to possible threats. Our sense of smell is able to distinguish blood kin by scent, and not only can it identify danger through picking up the scents of smoke, death, gas, etc., but can even pick up on fear, stress, and disgust in fellow humans.

Indeed, while the human sense of smell isn’t up to par with animals, studies have shown that we can track a scent trail in the same way dogs do, and that the reason we’re not better at it than we are, is that it’s a skill that has to be developed through practice. Consummate outdoorsman of days gone by who were highly observant of their surroundings often reported becoming able to track an animal by scent.

While both animals and humans process smell in automatic ways — when the smell of freshly baked cookies hits you, your tummy instinctively grumbles — human smell is in one way superior to the animal variety: we have the ability to consciously analyze smells and interpret what they might mean.

Smell can thus help you identify friend or foe, navigate an area — if we’re close to a factory or dump or a grove of pines or the campfire of home base, our nose will let us know — and even track game.

Touch & Taste

Touch and taste are two senses that are incredibly enriching for those seeking to live more mindfully and fully immerse themselves in their experiences. But for the purposes of being situationally aware of risk and danger, you won’t use them as much. Touch can come in handy though when you’re trying to navigate in the dark, and must let the sensations of your feet and hands lead the way.

Training for Observation: 10 Tests, Exercises, and Games You Can Play to Strengthen Your Situational Awareness

“As a Scout, you should make it a point to see and observe more than the average person.†—Scout Field Book, 1948

If our senses are truly as amazing as we’ve just described, and what holds us back from using them more is allowing them to default to autopilot, then we have to find ways to intentionally exercise and challenge them in order to give them full play.

Mastering situational awareness involves learning how to observe, interpret, and remember. The following exercises, tests, and games are designed to strengthen these skills while activating the latent powers of your senses.

Some of the games and exercises can be practiced alone, while others would work best in groups, such as a club, gathering of friends, or Boy Scout troop (several of the ideas in fact come from the 1948 edition of the Boy Scout Fieldbook). The games are also great to do as a family — they’ll keep your kids entertained without your having to reach for the smartphone!

1. “Kim’s Game”

In Rudyard Kipling famous novel Kim, Kimball O’Hara, an Irish teenager, undergoes training to be a spy for the British Secret Service. As part of this training, he is mentored by Lurgan Sahib, an ostensible owner of a jewelry store in British India, who is really doing espionage work against the Russians.

Lurgan invites both his boy servant and Kim to play the “Jewel Game.†The shopkeeper lays 15 jewels out on a tray, has the two young men look at them for a minute, and then covers the stones with a newspaper. The servant, who has practiced the game many times before, is easily able to name and exactly describe all the jewels under the paper, and can even accurately guess the weight of each stone. Kim, however, struggles with his recall and cannot transcribe a complete list of what lies under the paper.

Kim protests that the servant is more familiar with jewels than he is, and asks for a rematch. This time the tray is lined with odds and ends from the shop and kitchen. But the servant’s memory easily beats Kim’s once again, and he even wins a match in which he only feels the objects while blindfolded before they are covered up.

Both humbled and intrigued, Kim wishes to know how the boy has become such a master of the game. Lurgan answers: “By doing it many times over till it is done perfectly — for it is worth doing.â€

Over the next 10 days, Kim and the servant practice over and over together, using all different kinds of objects — jewels, daggers, photographs, and more. Soon, Kim’s powers of observation come to rival his mentor’s.

Today this game is known as “Kim’s Game†and it is played both by Boy Scouts and by military snipers to increase their ability to notice and remember details. It’s an easy game to execute: have someone place a bunch of different objects on a table (24 is a good number), study them for a minute, and then cover them with a cloth. Now write down as many of the objects as you can remember. You should be able to recall at least 16 or more.

Here’s an opportunity to play Kim’s Game right now: look at the illustration below for 60 seconds, then scroll past it, and see how many objects you can remember!

How did you do? Better keep practicing!

2. Expand and Enhance Your Field of Vision

Most of us, though we don’t realize it, walk around with tunnel vision. We’re concentrating on a few things directly around or ahead of us, and everything else drops out of our line of sight. So when you’re walking around, remind yourself to take in more than you usually do. Intentionally look for details in your environment you’d ordinarily overlook. Take note of peculiar features in the landscape, what people are wearing, side roads, alleyways, car makes and models, signs, graffiti on the wall — whatever.

To practice expanding your field of vision when you walk, follow these tips from the Boy Scout Fieldbook:

“Learn to scan the ground in front of you…Let your eyes roam slowly in a half-circle from right to left over a narrow strip of land directly before you. Then sweep them from left to right over the ground farther away. By continuing in this way you can cover the whole field thoroughly.â€

3. What’s That Sound?

Put up a blanket in the corner of the room. Then take turns standing behind it and making noises with random objects that the rest of the group has to try to identify. The more obscure and challenging the noises people can come up with, the better — think striking a match, peeling an apple, sharpening a knife, combing your hair, etc.

4. Eyewitness Test

Invite someone who your Scouts/friends don’t know to a group gathering. Have them come in for a few minutes and then leave. Then have everyone write down a physical description of the stranger and see how accurate they are.

5. Navigate by Touch and Feel

Can you dress yourself quickly in a pitch black room? Can you walk through the dark woods without a flashlight? Can you walk around the house blindfolded? Practice maneuvering and navigating without the use of your eyes.

6. Whose Nose Knows?

Have one member of a family/group fill paper cups with a variety of fragrant materials — orange rinds, onion, coffee, spices (cinnamon, pepper, garlic, etc.), grass, Hoppes No. 9 (any of the sources of these manly smells are good candidates) and so on. Then hand the cups to blindfolded participants, who take a sniff, and pass the cup on. Once the cup has been re-collected by the facilitator, the participants write down what they smelled.

7. Feel It

Similar to #6, but place different odds and ends into a box that then gets passed around. The participants have to feel the object and identify it from touch alone.

8. Observation Scavenger Hunt

This is a great one to do with kids, and can turn a long walk in the woods or the city, in which they might be prone to complain, into a fun game, and chance to strengthen their powers of observation! Before you set out, come up with a list of things the kids need to find; for example, on a nature walk you could put down things like a bush with berries, a bird’s nest, moss, a pine cone, etc. As you walk along, the kids will be on the lookout for the listed items, and every time they’re the first to spy one, they can mark another item off their list. See who can find the most things. It doesn’t have to be a competition either; you can all look for the items together as a family and simply keep one checklist.

9. Exit Interview

When you go to a restaurant or other place of business with your family, make a note of a few things about your environment: the number of workers behind the counter, the clothing and gender of the person sitting next to you, how many entrances/exits there are, etc. When you leave and get into the car to head home, ask your kids questions like “How many workers were behind the counter?†“Was the person sitting next to us a man or a woman?†“What color was his/her shirt?†“How many exits were there?â€

10. People Watching With a Purpose

In Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study In Scarlet, Dr. Watson first becomes apprised as to his future companion’s keen powers of observation and deduction. When the pair notices a man walking down the street looking at addresses and carrying a large envelope, Holmes immediately identifies the stranger as a retired Marine sergeant. After the message bearer affirms this identity, Watson is entirely startled at Holmes’ observational powers. “How in the world did you deduce that?†he asks. The detective then offers this explanation:

“It was easier to know it than to explain why I know it. If you were asked to prove that two and two made four, you might find some difficulty, and yet you are quite sure of the fact. Even across the street I could see a great, blue anchor tattooed on the back of the fellow’s hand. That smacked of the sea. He had a military carriage, however, and regulation side-whiskers. There we have the marine. He was a man with some amount of self-importance and a certain air of command. You must have observed the way in which he held his head and swung his cane. A steady, respectable, middle-aged man, too, on the face of him — all facts which led me to believe that he had been a sergeant.”

“Wonderful!” Dr. Watson exclaims.

“Commonplace,” Holmes replies.

If you’d like powers of deduction similar to the resident of 221B Baker St., practice people watching with more deliberation than is usually lent the pastime. Notice the clothing, tattoos, and accessories of passersby, and observe their manners and how they carry themselves. Then try to guess their background and occupation.

With enough practice in this and the other exercises and games outlined above, your senses will be heightened, your powers of observation will increase, and your situational awareness will be strengthened. Soon you’ll be able to say with Holmes: “I have trained myself to notice what I see.â€