When we cover topics that are a little deeper than say, Frank Sinatra’s slang, there are always some people who pick up what we’re laying down, some who understand it but respectfully disagree, and others who simply misinterpret the article. The latter happens either because they did not have sufficient faculties to understand it or because we failed to write it in an understandable way. Whichever was the case, I noticed some misconstrued conclusions being drawn from last week’s article on “Scarcity, Luxury, and Proving One’s Manhood.” So I wanted to take the opportunity to flesh out the topic a bit more. At the same time, I realized that while this blog is called the Art of Manliness, I’ve never really sat down and explained exactly what I believe manliness to be. So that’s what I’d like to do today. Pull up a chair and let’s get to it.

The Need to Plant Manliness in a Firm Foundation

While there are some ageless principles of manliness, characteristics celebrated by hundreds of different cultures in many different eras, some of the ideals of manhood have varied across peoples and time periods. These aspects of manliness were planted in transitory parts of culture.

For many ancient cultures, manhood was rooted in being a warrior. But it was a battlefield-specific manhood ill-prepared for life during peacetime. In early American history, manhood was connected with being a yeoman farmer or independent artisan. But when the Industrial Revolution moved men from farm to factory, men wondered if true manliness was possible in the absence of the economic independence they once enjoyed. In the 20th century, manhood meant being the familial breadwinner. But during times of Depression and recession, and when women joined the workforce in great numbers, men felt deeply emasculated. And in many cultures in many different times, being a man meant being part of a privileged class or race; in the United States, men owned slaves who were but 3/5 the equivalent of “real men.†When class and citizenship became achievable for anyone willing to put in the work, men felt that not only their position of privilege was under attack, but their very manhood:

Manliness as Virtue

While the definition of manliness has been endlessly discussed and dissected in scholarly tomes, my definition of manliness is actually quite straightforward. And ancient.

Aristotle set out in his Nicomachean Ethics a code of ethics for men to live by. For Aristotle and many of the ancient Greeks, manliness meant living a life filled with with eudaimonia. What’s eudaimonia? Translators and philosophers have given different definitions for it, but the best way to describe eudaimonia is living a life of “human flourishing,” or excellence. Aristotle believed that man’s purpose was to take actions guided by rational thought that would lead to excellence in every aspect of his life. Thus, manliness meant being the best man you can be.

For the ancient Romans, manliness meant living a life of virtue. In fact, the English word “virtue” comes from the Latin word virtus, which meant manliness or masculine strength. The Romans believed that to be manly, a man had to cultivate virtues like courage, temperance, industry, and dutifulness. Thus for the ancient Romans, manliness meant living a life of virtue.

So my definition of manliness, like Aristotle’s and the Romans, is simple: striving for excellence and virtue in all areas of your life, fulfilling your potential as a man, and being the absolute best brother, friend, husband, father and citizen you can be. This mission is fulfilled by the cultivation of manly virtues like:

- Courage

- Loyalty

- Industry

- Resiliency

- Resolution

- Personal Responsibility

- Self-Reliance

- Integrity

- Sacrifice

These virtues are manliness. And they can be striven for by any man, in any situation. From the soldier to the corporate warrior, from the firefighter to the stay-at-home dad. The ways in which men today can demonstrate these virtues may often be smaller and quieter than our forebearers, but that doesn’t make them any less important or vital.

At this point, someone will always jump in and say, “Wait, wait, shouldn’t women be striving for these virtues as well?â€

Absolutely.

There are two ways to define manhood. One way is to say that manhood is the opposite of womanhood. The other is to say that manhood is the opposite of childhood.

The former seems to be quite popular, but it often leads to a superficial kind of manliness. Men who ascribe to this philosophy end up cultivating a manliness concerned with outward characteristics. They worry about whether x,y, or z is manly and whether the things they enjoy and do are effeminate because many women also enjoy them.

I subscribe to the latter philosophy. Manhood is the opposite of childhood and concerns one’s inner values. A child is self-centered, fearful, and dependent. A man is bold, courageous, respectful, independent and of service to others. Thus a man becomes a man when he matures and leaves behind childish things. Likewise, a woman becomes a woman when she matures into real adulthood.

Both genders are capable of and should strive for virtuous, human excellence. When a woman lives the virtues, that is womanliness; when a man lives the virtues, that is manliness.

This is not to say I think the genders are identical. In the Code of Man, Dr. Waller Newell argues:

“We need to aim for the highest fulfillment of which all people are capable-moral and intellectual virtues that are the same for men and women at their peaks-while recognizing the diverse qualities that men and women contribute to this common human endeavor for excellence. We need a sympathetic reengagement with traditional teachings that stress that while men and women share a capacity for the highest virtues, their passions, temperaments, and sentiments can differ, resulting in different paths to those common pinnacles.”

Which is to say that women and men strive for the same virtues, but often attain them and express them in different ways. The virtues will be lived and manifested differently in the lives of sisters, mothers, and wives than in brothers, husbands, and fathers. Two different musical instruments, playing the exact same notes, will produce two different sounds. The difference in the sounds is one of those ineffable things that’s hard to describe with words, but easy to discern. Neither instrument is better than the other; in the hands of the diligent and dedicated, each instrument plays music which fills the spirit and adds beauty to the world.

Manhood and the Culture of Manhood

So how does all this connect with last week’s post about the “culture of manhood?â€

While I think that men and women can aim for the same goal of virtuous excellence, I don’t think we have identical weaknesses in that journey.

One of the weaknesses unique to men is that we have a hard time moving from boyhood into manhood. Yes, it’s a generalization, but women seems to have an easier and more natural transition into mature adulthood. Men, on the other hand, often need a push to leave adolescence behind. It’s easier to remain dependent, to stay as a consumer instead of a creator, to live for self instead of others.

Cultures across the world have recognized this. And as we talked about last week, the culture of manhood was designed to address the problem and to make manhood a desirable goal, something men would desperately want to attain. Immaturity was stigmatized. What the culture of manhood did was provide an external pull which drew as many men as possible into manhood-it was a wide net, a tide that lifted many boats and motivated the many men who would have otherwise been content to hide in the background and live safe, mediocre lives.

We see this played out in modern society where there no longer exists a strong culture of manhood-many men today are struggling to grow up and into honorable manhood. They’re never sure when they’ve crossed that threshold and have left behind the boy and taken on the mantle of manliness.

But even though we no longer have a strong culture of manhood, this does not mean there aren’t still individuals who seek out manhood on their own. These men are far fewer in number and are self-motivated. Their desire for manhood comes from within, from an internal drive.

But the attainment of manhood does not happen in a private vacuum. The men I admire today, the men who have attained manhood despite the odds, all have one thing in common: They sought and completed a rite-of-passage. They went looking for a challenge when others hid from it.

While last time we mentioned that opportunities to prove one’s manhood and experience a rite-of-passage were almost non-existent, this was meant to describe the state of things on a cultural level. Society has become so niche-fied and fragmented, that there no longer exists rites-of-passage that are recognized by the entire “tribe.â€

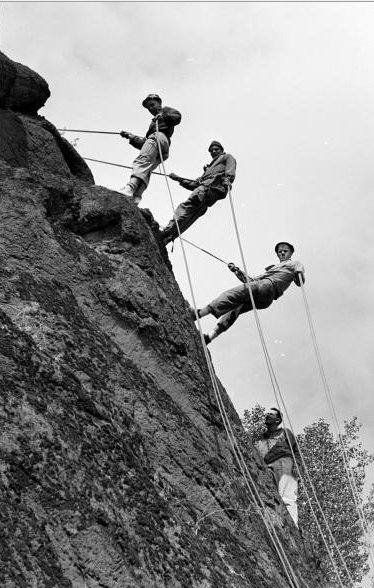

The challenge for today’s man is to become part of the little tribes that still offer this invaluable rite-of-passage. The military, churches, fraternal organizations, and adventures of other sorts can still help men cross the bridge into manhood. Or the passage may come to a man by accident, through the strong and resilient handling of the death of a father or the contraction of a disease. By whatever means it comes, the rite-of-passage breaks the gravitational pull of the path of least resistance, the path trod by so many, and propels a man onto the road to true manliness.

The loss of a culture of manhood surely has its downsides-the biggest being that fewer men will be prodded into mature manhood. But for the men with courage to still seek it out, the upside is that the manliness they find will not be born of outward pressures or cultural expectations but from inner values, conscience, truth, and heart.

The bottom line? True manhood still exists for those who seek it.