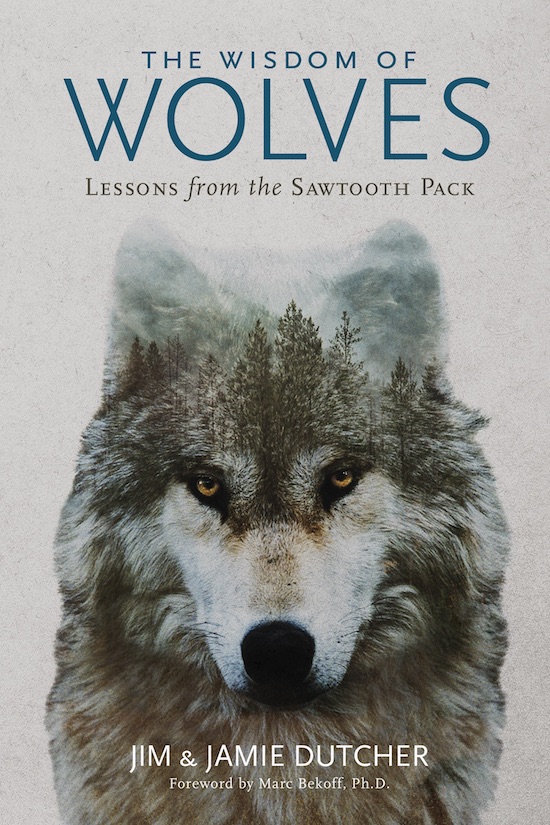

Between 1991 and 1996, Jim and Jamie Dutcher lived with and filmed a pack of wolves in Idaho. From this intensive field work came the award-winning documentary, Wolves at Our Door. The husband and wife team are out with a new book that highlights some of the things they learned on living a flourishing life from the wolf pack they were embedded within. It’s called The Wisdom of Wolves: Lessons from the Sawtooth Pack.

Jim and Jamie share what wolves can teach us about family, respecting your elders, play, the importance of belonging to a group, leadership, and what it really means to be an alpha wolf. Tune in for a fascinating conversation on a fascinating creature that has much to teach us humans.

Show Highlights

- How Jim and Jamie ended up spending time studying wolves

- Why research on wolves needs to be conducted in captivity

- How earlier studies on wolves ended up being somewhat misleading

- Why the term “alpha” is a misconception

- Other misconceptions about social hierarchies in wolf packs

- Why being a “lone wolf” is a very temporary situation

- Are wolf pack leaders domineering and aggressive?

- What’s the role of the “omega” wolf?

- How wolf personalities manifest in packs

- How the pups of a pack were reared

- The importance of play and why wolves play so much

- The culture of learning in wolf packs

- How wolves care for the elderly of their pack

- Why do wolves howl at the moon?

- What happens when wolf packs encounter one another?

- The relationship between wolves and ravens

- What happened to the Sawtooth Pack after the Dutchers finished their study?

- How wolves respond to the death of a pack member

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- How to Really Be Alpha Like the Wolf

- The Myth of the Alpha Male

- Wolves at Our Door

- Play It Away

- The Importance of Roughhousing With Your Kids

- AoM series on status

Connect With the Dutchers

Living With Wolves on Facebook

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Slow Mag. A daily magnesium supplement with magnesium chloride + calcium for proper muscle function. Visit SlowMag.com/manliness for more information.

The Great Courses Plus. Better yourself this year by learning new things. I’m doing that by watching and listening to ​The Great Courses Plus. Get one month free by visiting thegreatcoursesplus.com/manliness.

Wurkin Stiffs. The only magnetic collar stays. Fix your collar today — your shirts will thank you. Go to wurkinstiffs.com, enter my code “manliness” and get 25% off.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Between 1991 and 1996 Jim and Jamie Dutcher lived with and filmed a pack of wolves in Idaho. From this intensive field work came the award-winning documentary Wolves at Our Door. The husband and wife team are out with a new book that highlights some of the things they learned living a flourishing life in the wolf pack they were embedded within, it’s called The Wisdom of Wolves. Jim and Jamie share what wolves can teach us about family, respecting your elders, play, the importance of belonging to a group, leadership, and what it really means to be an alpha wolf. Tune in for a fascinating conversation on a fascinating creature that has much to teach us humans. After the show is over check out the show notes at aom.is/wisdomofwolves. And Jim and Jamie join me now via Skype.

Jim and Jamie Dutcher, welcome to the show.

Jamie Dutcher: Well thank you so much for having us, Brett.

Jim Dutcher: Yes, thank you very much.

Brett McKay: So you two recently published a book, The Wisdom of Wolves, and this is based on a project you all did back in the ’90s. You filmed from 1991 to 1996 a pack of wolves and it’s call Sawtooth pack. But let’s start from the background of that. What was the impetus behind the project of filming a pack of wolves, for such a long time too?

Jim Dutcher: Well, I’ve been a filmmaker that specializes in animals that you just don’t get see in the wild: mountain lions, beavers, undersea subjects. And after finishing a successful film on mountain lions we put together a proposal with ABC Television to do a special on wolves. But you just can’t go out and find a pack of wolves and film them in a meaningful way. I mean you can, but they’re so far away, they’re so intelligent that they change their behavior and run away. We wanted to be able to get into their social lives. So we set this project up with puppies – bottle-fed them from the moment they opened their eyes and camped with them for six years afterwards. But we gained their trust by being with them from the moment their realized they were here on this planet.

Brett McKay: And where did you all get the wolf pups from, the initial wolf pups?

Jim Dutcher: Well, there is a woman up in Montana that inherited or just took over a pack of wolves, they were being experimented with and they were in Alaska. And she said, “If you give me the pack I’ll take care of them, please don’t euthanize them.” The project was finished and they were going to put them all to sleep. So she had also seen the mountain lion film and thought we could do a lot of good for wolves and she gave us puppies. So we started the Sawtooth pack with a pack of puppies, four of them.

Brett McKay: Wolves, we’ll talk about this later on, but they explore and their territories can be large and they’ll move from territory to territory. How did you keep them contained within a certain area so you could film them?

Jamie Dutcher: Well, they were in an enclosed situation and we actually had the largest wolf enclosure in the world, it was 25 acres. And it’s important to note that all behavior studies that have been done on wolves have to be done in captivity because you can’t get close enough to them. But most of these studies had been in very small enclosures of one to three acres. So we had the largest enclosure in the world, 25 acres. And it’s true that wolves do have huge territories, but since the pack basically grew up in this area they were very content, they didn’t pace the fence. You could lose a wolf for days in this area. We had a very mix terrain, we were at the foot of the Sawtooth mountains, we had alpine meadow, we had forests, we had streams, it was quite varied and they were very comfortable in that location because, of course, their family was there.

Brett McKay: As you just mentioned, a lot of previous studies on wolves were done on captive wolves and in a really small area. How did those studies maybe mislead us about … What are some of the things that we maybe got wrong about wolves by studying captive wolves and putting them in such a small area?

Jamie Dutcher: Well, I don’t want to speak for every study but I know that there were some researchers that would enter enclosures and would dominate the wolves. And by doing that, by making the wolves submit you’ve changed their behavior, you’ve just altered things going on. And I think also being in a smaller situation can lead towards maybe some unnecessary aggression.

We made sure that even though we bottle-fed these wolves from pups just as they were opening their eyes so they would trust us, we never treated them as pets and we never tried to dominate or be submissive to them, we were very, very neutral. And I think that allowed us access to this intimate behavior without really affecting the way they lived their lives. We would have our film gear and our sound gear and we would be out with the pack and we wouldn’t miss a beat because we were basically like the furniture, they wouldn’t just stop and go, “Oh, who’s here?”

I think also having this larger area gave us an opportunity to really see these wolves’ lives unfold to us. And they revealed to us how compassionate and caring they are for one another. And even though the great apes are more closely related DNA-wise – and wolves also created the dog – wolves’ social behavior is really so much like our own. You can watch wolves and you can see your colleagues at work, you could see kids on the school playground. It was a really wonderful way to observe them and learn a lot more.

Jim Dutcher: One another reason for approaching this project the way we did with captive wolves. If you go out into the wild and you habituate a pack of wolves and gain their trust, wolves are hunted in the three western states where they mostly live: Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho, and if you gain the wolves’ trust then maybe the next time a wolf sees someone it may not be a camera being pointed at them, it’ll be a gun. So we didn’t want that to happen. That was the reason we approached the project the way we did.

Brett McKay: Jamie, you just talked about the social life of wolves. Wolves are famous for their social hierarchies, there is an alpha wolf, a beta wolf. But I think there’s a lot of misconceptions about how wolf hierarchies work. What do you all think are the main misconceptions about wolves’ social hierarchies that people might have?

Jamie Dutcher: I think one of the biggest misconceptions is the term “alpha”. And alpha seems to be falling out of favor with a lot of people. But we still use it to describe the leader of the pack. The alpha is generally the father of the pack, the alpha male and female are the parents of the pack, generally, and so they would be the parents in your own family, and they are the ones that really determine how the day-to-day operations of the family work. And I think a lot of people have this idea, “Oh, the alpha, it must be this tough, strong, aggressive …” We use it in a very negative way nowadays, where really the alpha, our alpha, was a very benevolent leader, he led with kindness, he was a very caring leader and father of the pack. And it really showed us that there is more to being an alpha than just strength. They take care of the family, they decide who is going to eat first and last. It’s a very sensitive, caring thing.

Another interesting point that they have been discovering actually in Yellowstone since the wolf reintroduction is that … It was always thought that it must be the alpha male that leads the pack. There have been sightings where people have been watching the wolves and the alpha male would get up and stretch and get ready to go somewhere and the rest of the pack doesn’t pay attention. But if the alpha female gets up everyone stands to attention, they know something is going on.

Jim Dutcher: We’re going some place.

Jamie Dutcher: Yeah, we’re going some place, we need to be ready. So the female has a lot of to with it as well. So I think one of the major misconceptions is that this alpha is this tough, lead with an iron fist kind of leader, and it really isn’t that way. Wolves, they’re individuals and all families are different, but generally they don’t need to lead with an iron fist.

Jim Dutcher: Brett, another misconception is that the pack, that it’s just this mob that got together in the forest and went out to make a killing. It really isn’t, it’s a family. It’s mother, father, aunts and uncles, grandchildren, grandparents. They may adopt another wolf, another wolf could join them, sometimes not. But by and large it’s a family.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I learned that just recently. I thought wolves just got together and they sort of fought it out to see who is the alpha and that was it. But no, it’s a family and it’s the mom and the dad, they’re the leaders.

Jamie Dutcher: Yeah, boy meets girl and they have a family and then it all goes from there.

Jim Dutcher: Another misconception is the lone wolf. That’s a disperser, that’s a wolf that wants to go out and find another wolf. It’s a very temporary situation. Perhaps the wolf sort of outgrew the family it was in or had aspirations of being the leader and yet there was a strong leader so he or she goes off and looks for a mate, another disperser, and they form another pack. But they have to do this pretty quickly because it’s very difficult for a wolf in the winter time to feed itself because the smaller animals are under the snow and hibernating but elk and deer and animals that they feed upon, you need teamwork to bring them down.

Jamie Dutcher: Yeah, and this misconception of people saying, “Oh, I’m a lone wolf, I don’t need anybody.” Wolves need each other, they need a family and they need to belong. So it’s a very temporary situation in which a wolf doesn’t want to be in for a very long time.

Brett McKay: Right, so there’s some wisdom we can get right there just on leadership.

Jamie Dutcher: Absolutely.

Brett McKay: I think if we all look at the leaders that inspired us the most, they weren’t domineering, they weren’t aggressive, they weren’t loud. And they could be if they need to be, but mostly they were just calmly leading the group.

Jamie Dutcher: Sure, lead with kindness.

Brett McKay: And with the lone wolf thing, in order for humans to survive and thrive we need each other as well, we need a group.

Jamie Dutcher: Absolutely, absolutely.

Brett McKay: So we talked about alpha wolves. There are omega wolves. So they’re sort of like the low man on the totem pole. But despite that, the you describe the omega in this pack, the wolves treated him … They kind of bullied him sometimes but they also saw that he had a role as well. So what is the role of an omega wolf in a wolf pack?

Jamie Dutcher: In our pack the omegas seemed to be the instigators of play, using play to diffuse pack tension. And they could always get the rest of the wolves in a light-hearted mood for a great game of tag. But like you had mentioned, they are also the focus of pack aggression, they’re the low man or woman on the totem pole, and they do get picked on. They generally are forced to eat last, they have to wait until everyone is finished. But they really have an important role to play within the pack.

For instance, when we were just talking about dispersing wolves, an omega wolf has a definite position. The omega wouldn’t generally be a disperser, he’s got a really definite spot in the pack and knows what that spot is. But all the same, the wolves still really cared for him. And in our pack there was a point where the omega seemed to be allowed to retire from the position and the rest of the wolves stopped picking on him. And unfortunately, they found another to pick on a little bit. And what was really great is that Lakota, the old omega, never picked on this new omega. It’s like he knew what had happened and just wasn’t going to pitch in on that.

But one really touching story with the omega had to do with another wolf in the pack which is the beta wolf or second in command, generally. And we started noticing when we would slow down our film and watch it in slow motion that Matsi, the beta wolf, if there was a dispute going on with the omega, he would actually run into the fray of the wolves and the dispute going on and break it up so the omega could get away. And after watching this more and more we started to notice that the two of them hung out together, they would sleep together, the beta wolf would let the omega wolf jump on his back, which another wolf would never let happen, and they really had an incredible friendship. And this beta wolf, the only way you could say it is really took him under his wing and just made sure things didn’t get out of hand, which was quite sweet and the way that we should be taking care of our weaker members of our family and community.

Brett McKay: How are omegas determined? Is it just personality, they’re just timid? How does that shake out?

Jamie Dutcher: Yeah, generally it seems to be their personality. Lakota was a very shy wolf. Although, interestingly he was bigger than the alpha. The alpha was actually his brother, but he was bigger than the alpha wolf. So it seems more to do with personality than it does just physical weakness.

Brett McKay: So going back to this idea of wolves and family being so important, one of the things I liked that was really touching was how much all the wolves were invested in the pups of a pack, and not just the parents. What do the other adult wolves do to help rear these wolf pups?

Jim Dutcher: As I said, we started with puppies but we had other pups given to us as the years went on, until finally our alpha pair, she dug a den and we had puppies of our own. But all along the way you could see these unrelated wolves caring for pups. And we would keep them separate for a while just so we could bond with them and nurture them and feed them with used milk bottles around the clock, and as they got older we would play with them a lot, just being with them. So they were fenced off. And the other wolves would sometimes bring presents and slip them through the chain-linked fence for the younger wolves. I always thought that was so sweet.

Jamie Dutcher: Little pieces of hide and bone, it was pretty cute. But all the members of the pack take care of the pups. They’re generally born to the alpha pair, but you’ll have one wolf that will step up to be the puppy sitter, you’ll have others that will help become teachers, and then there are others that are just generally playmates and nothing more than clowns for the pups. But they all … It’s really interesting how wolves just love pups, whether related or unrelated. They really take care of them.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I think you made the point that biologists have noted in wolves when pups are born into a pack the non-parent adult wolves kind of enter like a second pup phase and they become very playful. And to me, it reminded me of goofy uncles. That’s the job of a human uncle, right? You’re there to play with your nieces and nephews, do the things that the kids’ parents would be like, “No, don’t do that, it’s not safe.” Aunts and uncles are there like, “No, we’re going to do some crazy stuff. I got to teach you how to have fun.”

Jamie Dutcher: Oh, absolutely. And we absolutely had the goofy uncle. One of the mid-ranking wolves, Amani, was totally a complete clown and he had no interest in teaching the pups or nurturing them, he just wanted to play and they loved him.

Jim Dutcher: And in our book we have other stories of other wolves we have come to know. And one of them is from the wolf watchers out in Yellowstone watching a similar type of wolf, a goofy uncle, that went off on its probably looking for gophers and ground squirrels and such, and must have come upon a carcass of a huge bison and thought … I don’t know, what ever he thought. He picked up the skull, a monstrous skull, and carted it back, which would probably have been 10 or 15 minutes back to the rendezvous stop where the pups were, his younger brothers and sisters, and he gave that to them.

Jamie Dutcher: Yeah, it took hours to get it.

Jim Dutcher: It took him hours to do this and he had to put it down and lift it up. And we’re just, “Why he did that?” And he just seemed to care about the younger pups.

Brett McKay: I love that, that was some of my favorite stories from the book. Speaking of play, you highlighted in the book that wolves, they play all the time. Why do they play? Do biologists know why wolves play so much?

Jamie Dutcher: I think it’s not so different than humans, really. I mean we all play and we play to hone different skills. For wolves play helps them reinforce their bonds with each other but it also helps teach them hunting techniques, stalking, just all kinds of different skills, testing where they’re strong and where they might be a little weak. So play is a vital part of learning and becoming a stronger wolf. But also for the sheer joy of it. Wolves can be seen on sides of mountains just running like crazy and chasing each others’ tails, and they do it for the sheer joy of it. But there is also the education factor involved.

Brett McKay: And it does seem too that play, somehow it can flatten the social hierarchy temporarily. So you talk about Lakota was the omega, Kamots was the alpha, they’re brothers, and Lakota would instigate play and Kamots would play with Lakota but he would let Lakota win, which was interesting because Lakota is the omega.

Jim Dutcher: Yeah, role reversals where Lakota, the omega, would actually chase the alpha and the alpha would just let him catch him. And it was really touching to see. So you have to think about this. That wolf, the alpha, must have perceived what he meant to his brother to let him do that. So the perception of just being the leader but also being a friend, I thought that was really touching.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I think it’s very similar to humans in a rough housing.

Jim Dutcher: And they pass on knowledge. A wolf pack, they learn certain techniques. In Alaska there was a pack of wolves that specialized in feeding on Dall sheep on a mountain face. And if they climbed up the cliffs of the mountain to try to get to the sheep, well the sheep would just climb higher and get out of the way. But they learned a technique of going around the backside and coming down from above, and they were very successful at doing this. But sadly, if the wolves wander out of national parks they get trapped and hunted, and these wolves lost their alphas and the younger wolves never learned how to hunt sheep that way, so this culture of learning was broken up.

Jamie Dutcher: So these wolves never went back to hunting Dall sheep. It is quite sad.

Jim Dutcher: And we have hunting here in Idaho and Wyoming and Montana, and they hunt wolves and they break up packs. And when you break up a pack – a good sized pack would be maybe a dozen wolves – and if you start hunting them, and the younger ones are usually ones that get shot, but also the leaders, they stand up to the perceived danger. And if you kill this knowledge then the wolves that are left are broken up into smaller packs of twos and threes and they’re dramatically affected by this and they are desperate for food and so they go after what is easy, and that’s sometimes livestock. So hunting wolves actually makes it worse for ranchers.

Brett McKay: I think you also highlighted a story too where there was a pack that had developed a culture of hunting bison together as a team?

Jamie Dutcher: Yes.

Brett McKay: Right. And then they killed the elder wolves and then that culture stopped, they stopped hunting bison.

Jamie Dutcher: Right, same thing. In Yellowstone national park, bison, it’s very specialized. Most of the wolf packs hunt deer and elk, but there was one pack that really had honed its skills at hunting bison. They were a much bigger pack and they really worked as a team to bring them down. And losing that culture, that knowledge really devastates the family.

Brett McKay: And I think this is, again, the wisdom of wolves. There’s a role for elderly people in our own communities because they have knowledge that’s vital, that can help a family or a community thrive.

Jamie Dutcher: Yes, that’s very true. There’s a gal, Kira Cassidy, who’s been doing research in Yellowstone and she works with us. And she was studying the effect of older wolves on their packs. And it turns out that a wolf pack is two and half times more successful when older wolves are in the pack than not. So you can have a smaller pack with older wolves and then a larger pack with no older wolves, and the smaller pack with older wolves will do better. And that’s because these wolves, as in human culture, they’re the carriers of the knowledge, they’re the carriers of the history. They know where to cross the rivers. If they get into a dispute with another pack over, let’s say, territory, those older wolves have probably come across the other wolves before so they know the strategies, they know what works and what doesn’t work. They may not take place in the actual dispute or the disagreement, the argument, the fighting, but they are the ones that really guide the younger wolves on how to act and how to conduct themselves. It’s really important. And in today’s culture we tend to marginalize our elders, but we really have so much to learn from them.

Brett McKay: A wolf howling at the moon is this archetypal image, and you all filmed these. And they don’t just do it alone, they do it in unison, which I think is interesting. Do biologists know why wolves just howl together in unison?

Jamie Dutcher: Oh gosh, I did all the sound recording and I like to say that wolves howl for more reasons that we will ever know. They howl when they’re just happy, when they feel good, they’ll howl after a meal, they’ll howl to search for each other. There’s a thing called a pack rally where generally the alpha will start howling and then all the other wolves will come in and it’s this big, kind of jazzy, soulful, hysterical howl, and then all of a sudden it’ll start break into play and then it’ll die off. And so it really serves a huge purpose. Wolves will also howl by themselves we find to check in on each other. In the middle of the night you might get one wolf that’ll howl and it’s almost like he’s saying, “Hey, I’m here, I’m fine.” And then another wolf will howl off in the distance and it’s like, “Okay, I’m over here.” So it’s pretty spectacular.

But their array of communication is so varied that we’ve got howls, growls, whines, barks, these sounds that I like to call Chewbacca sounds because it sounds actually like the Star Wars character Chewbacca. It’s really a lot of fun.

Jim Dutcher: The way we had our camp set up, we were living in their territory and we built a platform, a yurt and a wall tent. But we circled the whole thing with chain link. And so when we go to sleep at night, our heads on our cots were very close to the canvas wall which was close to the chain link, and there was a wolf that always liked to hang out there. Wahots would have his little bed right there. I don’t know, during the day he seemed to be a little bit shy and aloof, but at night our muffled sounds reminded him of being bottle-fed as a youngster. But he would just stay right there and the other wolves would start to howl off in the distance and he would howl and just launch us out of bed. It was such a surprise in the middle of the night.

Brett McKay: So it sounds like howling, it’s sort of a social thing. It’s sort of like how we sing together. I think they’ve done studies on humans, when you sing together with other people it does all this stuff to your brain, it makes you feel good, connected, etc.

Jamie Dutcher: Yeah, it really does. And there’s a story in the book where we talk about … We were doing a presentation at a school in Connecticut. And as we walked into the auditorium and took the stage, in unison all the kids got up-

Jim Dutcher: 600 of them.

Jamie Dutcher: 600, and started howling. And we found out later that this was not planned, they all just did it. And you could just tell what a great time they were having howling, it was so social. And it took a bit to get them calmed down, but you could tell that they loved it just as much as wolves do.

Brett McKay: So maybe the tip: howl tonight with your family before you go to bed, or at least sing a song together, we can do that.

I know you all didn’t film this – or maybe you did and it just wasn’t in the book – but do we know what happens when a wolf pack encounters another wolf pack? Is there a conflict? Do they kind of mediate that conflict somehow? Do we know what goes on there?

Jamie Dutcher: Well we’ve not filmed it but it’s been observed in Yellowstone. And a lot of different things can happen and it depends upon the circumstances. Wolves will try to avoid each other and each others’ territory, but there’s times when wolves will have to move through another wolf’s territory. And if they come upon the other pack then there can be a pretty big dispute, a pretty big fight.

Jim Dutcher: But you have to realize, a lot of these packs in Yellowstone, they follow the elk out of the park and they get killed. And so they have to sort of stay in the park or they run the gauntlet of hunters outside the park, and they’re pretty effective.

Jamie Dutcher: So they do cross through each others’ territory quite a bit. It’s not often that there are serious problems but there can be conflicts. And that’s really not unlike early human cultures.

Brett McKay: Yeah. One of the interesting points you highlighted too was that unlike other animal species where, say, a wolf pack will take out all the adults, they won’t do that to the pups and they’ll actually adopt the pups. That’s interesting because I think gorillas, those kill all the baby gorillas, and then male lions do the same thing to lion cubs.

Jamie Dutcher: Yeah, and I think chimpanzees. And it’s really interesting. Certainly a young wolf or a pup could get caught up in the dispute and something could happen, but generally if one wolf pack takes over another pack after dispute, they will not kill the pups. Those pups are immediately taken into the family. And if you have a pregnant female, she’ll give birth and those pups are immediately taken in. It’s really a very culturally unique that I think we share. We adopt other offspring and it’s a really moving thing to see.

Brett McKay: That’s why dogs or canines and humans get along so well, the similarities are crazy.

The other super fascinating sort of tidbit in the book you guys highlight was the relationship between wolves and ravens.

Jim Dutcher: Oh yeah.

Brett McKay: What was going on there? What happens between these two?

Jim Dutcher: Well, the ravens would sort of tease certain members of the pack and fly real close or hop along on the ground and come up behind them and pull their tails. But ravens and wolves, they need each other symbolically. In the wild often ravens will lead wolves to a winter kill. And they’ll do this probably for a selfish reason because they can’t open the kill with their beaks and the wolves can. So they benefit from each other.

Jamie Dutcher: Yeah, so wolves will follow ravens to a winter kill and ravens will follow wolves on their hunt and there’s always little bits and scraps left over. And it was really fun to see that the ravens around us, they were scared to death of us, we could never get to them, but they would hang out with the wolves and as Jim said would pull their tails and try to get them to play and the wolves would sort of haphazardly snap at them and not really caring very much until they got irritated and walked away. But it was really as if the ravens were just kind of instigating some play like, “Come get me, come get me!” It was really great to see.

Jim Dutcher: But there was one time where we found a dead raven and it probably was killed by the wolf. And Jamie picked it up and kind of tossed it toward the wolves and the reaction was strange, because they would normally … If they killed a bird or a ground squirrel, rabbit, something like that, they would consume it or play with it and then eat it. But this, when Jamie threw the carcass to Matsi, the beta wolf, he kind of looked at it so sad and walked away. It’s like it was a mistake.

Jamie Dutcher: Yeah, like a tragic mistake.

Brett McKay: I thought that was really interesting and funny too, the picture of a raven picking up a wolf’s tail. I don’t know, I thought that was funny.

So what happened to the Sawtooth pack? You were filming then from 1991 to 1996. What happened to them after that?

Jim Dutcher: Well, we moved them to the Nez Perce reservation. Our permits with the forest service in the area that we lived in under the Sawtooth mountains, about an hour from our home here, that permit expired. And we renewed it as many times as we could, but we eventually had to find a permanent home so we moved them up to Winchester, Idaho, to the Nez Perce reservation and they lived out their lives there. One of them lived to be about 17 years old.

Jamie Dutcher: So they were in a similar situation because the one thing, we could not let them go free, they lost the one thing they needed to survive in the wild which, of course, was fear of humans. But that was never the plan. We had sort of hoped that by the time the Sawtooth pack no longer existed that there wouldn’t be a need for captive packs anymore. So they lived out their lives as ambassadors there.

Jim Dutcher: I’d like to mention one thing. One sort of breakout moment for me in the project came in the very first year of the project when we had another omega, a black female we called Mataki. And she would take and go off by herself because she would get picked on all the time so she just would be by herself some place in the territory. And a mountain lion spotted her and climbed the fence and killed her. But what was so amazing and changed me is when I watched how the wolves reacted to her death. They stopped playing. We talked about playing, it happens all the time. We didn’t see play for six weeks and they were very affected by being in the area where we found the carcass of this wolf, and we found fur way up in a tree and claw marks of a cougar up in the tree. But at the base of the tree we found claw marks of the wolves like they tried to chase this lion up the tree, and I guess she escaped somehow.

But they also howled differently. We talked about pack rallies, they would gather together and celebrate the solidarity of their pack. They stopped howling that way. They would howl separately and their howls were very searching, as if they were trying to call Mataki back.

Jamie Dutcher: And when they would walk through the area where she had been killed, their heads would go down, their ears would go back. They were clearly visibly upset. The only way to say it is that they were clearly mourning, they clearly missed her and were grieving her loss.

Jim Dutcher: And we’ve heard stories like this of wolves. In Alaska there was a famous pair that was being researched by Gordon Haber, and the alpha female stepped in a trap. And the pack and her mate stayed in the vicinity for a couple of weeks. And these traps don’t kill the wolves, they just linger there until they starve to death or perhaps a hunter comes along and finishes the job. But the hunter finally showed up two weeks later, the wolf was still alive, he shot the wolf. And the alpha male ran back into the park – and it was still winter – and he went back to the den site. And he dug up the den and cleared it all out for a litter that he would never father. And then after he finished that he ran back again to the trapping site. And when Gordon left him he was howling on a ridge over and over in the direction of the trapping site. So he was totally confused with what happened to his mate.

Brett McKay: That’s really sad. When did the last of the wolves die of the Sawtooth pack?

Jim Dutcher: I think it was 2014.

Brett McKay: Not too long ago.

Jamie Dutcher: Ripe old age of 17.

Jim Dutcher: Yeah, I think we got 98,000 emails. We have a nonprofit organization, we try to educate people about wolves. And people got to know about this wolf pack and so many stories, it was very touching.

Brett McKay: Jim And Jamie, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and the rest of your work?

Jamie Dutcher: Well thanks Brett. We invite everybody to visit our website livingwithwolves.org. There you can find a lot of information about wolves and our nonprofit. Living With Wolves is also on Facebook and Twitter. And also we just put out an interactive exhibit on our website which is a great educational tool for adults and kids to navigate and learn more about wolves.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well Jim and Jamie Dutcher, thank you so much for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

Jamie Dutcher: Thank you so much, Brett.

Jim Dutcher: Thanks, Brett.

Brett McKay: My guests today were Jim and Jamie Dutcher. They are they author of the book The Wisdom of Wolves, available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You’ll also find out more information about their work at livingwithwolves.org. And check out our show notes at aom.is/wisdomofwolves where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. And if you enjoyed the show and got something out of it I’d appreciate if you take one minute to gives us a review on iTunes or stitcher, it helps out a lot. As always, thank you for your continuous support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.