500 years ago, St. Ignatius of Loyola, a soldier turned religious convert, created the Society of Jesus. My guest today argues that many of the principles Ignatius used to guide the Jesuit order are just as applicable to living a flourishing life today.

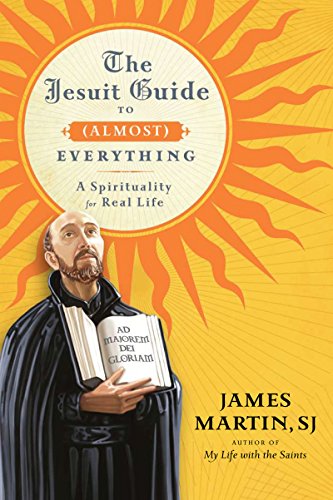

His name is Father James Martin, he became a Jesuit priest after a stint in corporate America, and he’s the author of The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything: A Spirituality for Real Life. Today Father Martin and I discuss why the insights of Ignatian spirituality have proven useful to people from various faiths and backgrounds, and what these insights can teach us citizens of modernity. We discuss why you should pay more attention to your desires, the benefits of living simply, and how to free yourself from what Ignatius called “disordered attachments.” We also explore how not to be disappointed with your friends, how to improve those relationships, and how to think the best of others and ourselves.

While Father Martin’s advice is obviously given in the context of faith, nonbelievers will also find plenty of insights in this show.

Show Highlights

- The story of Ignatius of Loyola and how the Society of Jesus came to be

- The sometimes humorous, but also tragic vanity of Ignatius

- How Fr. Martin found his way into the priesthood, and the Society of Jesus specifically

- 4 tenets of Ignatian spirituality

- The difference(s) between Christianity and Stoicism

- Why folks from all walks of life have appreciated the message of Fr. Martin’s book

- What is “the examen”? How does one practice it?

- Why should we pay attention to our desires?

- How do you learn to want to want the things you know are good?

- What are “disordered attachments”? How do they mess us up?

- How do we get over our disordered attachments?

- “Act like your best self would”

- How to live simply without becoming a monk

- What is the principle of the presupposition? How can it help our relationships?

- How to love people as they are

- Keeping and nurturing friendships in adulthood

- The virtue of obedience

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- AoM series on spiritual disciplines

- Thomas Merton

- What Do You Want to Want?

- You Can’t Return to Eden

- Agere contra — acting against

- Why You Should Go to Church — Even If You Aren’t Sure of Your Beliefs

- Want to Feel Like a Man? Then Act Like One

- Francis of Assisi

- Building Your Band of Brothers

- How Not to Be Disappointed With Your Friends

- On the Importance of Keeping in Touch With Old Friends

- 5 Types of Friends Every Man Needs

- Don’t Just Lead Well, Follow Well

- Doing Good vs. Doing Nothing

Connect With Fr. Martin

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Spotify. Spotify is making it easy for you to stream this podcast and many others like it on your mobile device, desktop app, and smart speaker. Open the app on your mobile device or desktop, click on the “browse†channel then click on the “podcast†section to find the Art of Manliness and many others.

Stitcher Premium. Marvel is unveiling their first scripted podcast ever, and it’s available exclusively on Stitcher Premium. In ​Wolverine: The Long Night​, you’ll be immersed in a murder investigation that explores a string of mysterious deaths in Burns, Alaska. To listen now, go to wolverinepodcast.com and use the code MARVEL for a free month of Stitcher Premium.

Proper Cloth. Stop wearing shirts that don’t fit. Start looking your best with a custom fitted shirt. Go to propercloth.com/MANLINESS, and enter gift code MANLINESS to save $20 on your first shirt.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. 500 years ago St Ignatius of Loyola, a soldier turned religious convert, created The Society of Jesus. My guest today argues that many of the principles Ignatius used to guide the Jesuit order are just as applicable to living a flourishing life today. His name is Father James Martin. He became a Jesuit priest after a stint in corporate America, and he’s the order of the book The Jesuit Guide to Almost Everything.

Today, Father Martin and I discuss why the insights of Ignatian spirituality have proven useful to people from various faiths, or lack of it, and backgrounds, and what these insights can teach us, citizens of modernity. We discuss why you should pay more attention to your desires, the benefits of living simply, and how to free yourself from what Ignatius called disordered attachment. We also explore how not to be disappointed with your friends, how to improve those relationships, and how to think the best of others and ourselves.

While Father Martin’s advice is obviously given in the context of Christian faith, he’s a Catholic priest after all, non-believers will also find plenty of insights in this show. After it’s over, check out the show notes at aom.is/jesuit. Father Martin joins me now via clearcast.io.

Reverend James Martin, welcome to the show.

Fr. Martin: My pleasure.

Brett McKay: You wrote a book, The Jesuit’s Guide to Almost Everything, and what you look at is, it’s sort of a layman’s explanation of the Jesuit order and their philosophy, and their founder Ignatius. How do you say his name?

Fr. Martin: Ignatius.

Brett McKay: Ignatius. All right, Ignatius. St Ignatius has a really interesting story. Tell us about him and how he started the Jesuit order.

Fr. Martin: Sure. He was born in 1491 in the Basque country of Spain. He started out as a page to a knight, and then became a soldier. He was kind of vain. He describes himself in his own autobiography as vain. He was very concerned with his hair by the way, he kept talking about that. He is injured in a battel in 1521 in Pamplona, and that prompts him to reconsider his life. He ends up recuperating and reading books about Jesus and about the saints.

He starts to have these experiences in prayer which make him realize that the former way of life that he was living, trying to impress people and doing great deeds, was not as satisfying as trying to live a holy life, and that leads him to, through a number of choices and turns found what’s called The Society of Jesus, or, which is better known as the Jesuit. That’s a thumbnail version of his life. He was a pretty headstrong guy. The old joke in the Jesuits is it took a cannonball to turn his life around, which is how he got injured.

Brett McKay: Yeah. It’s funny, his vanity, another instance of his vanity was he hid his leg, or something. He was worried about how his legs would look in stockings, so he wanted to do this surgery, and it just messed it up even more.

Fr. Martin: Yeah. The tights of the time I guess showed off your legs I guess, and he had the surgery done as you were saying, after the cannonball hit him, and it wasn’t good enough. There was a little bone protruding. Without anesthesia he had the doctor I think saw the bone off, which I can’t imagine how painful that must have been. The reason he puts that in the book is to show you how vain he was, and to say that he was a slave to his own appearance.

Later on he decides he needs to move away from that. He lets his hair grow long and his fingernails grow. He even says, “Well, that doesn’t make sense either,” because it scares people. So he opts for a kind of moderation, and that’s a very Jesuit thing to do, whatever works best in the situation.

Brett McKay: You also have an interesting story. How did you find your way into the priesthood? And why did you choose The Society of Jesus?

Fr. Martin: I went to the Wharton School of Business at Penn, graduated in 82, and then worked for six years in corporate America at GE, and really found myself miserable and not in the right place, square peg in a round hole. I came upon a book by a guy named Thomas Merton, who Trappist monk, and that got me thinking about doing something different. Funny enough, to answer your question, the Jesuits, I knew nothing about the Jesuits. I mean, most Catholics know them for their schools, like Georgetown and Fordham and BC. The old joke is, we started school so they could win basketball scholarships and tournaments. Gonzaga, places like that.

But I knew nothing about them, and someone suggested them as being congenial to me. I took one look and thought, “This is it. This is for me.” It’s a very accessible and friendly spirituality, and the guys I met were great and funny and smart and hard working. Yeah, it was a good fit. So I entered 30 years ago this year.

Brett McKay: Wow. So it didn’t take a cannonball for you.

Fr. Martin: It did not. Although, the job at GE was sufficiently difficult, not in terms of doing it but my distaste for it. I started to get stress related illnesses and headaches and migraines, so a different kind of cannonball. A kind of miserable life situation that prompted me to be more open. I think God really can enter into your life a little bit more when you’re vulnerable. That doesn’t mean God punishes us and makes us sick or something like that, but when I was down and out and feeling like I didn’t know where to go, my defenses were down and I think God was able to break in a little bit more easily.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about Ignitian spirituality and his philosophy. There’s four tenets, basic tenets. What are those four tenets?

Fr. Martin: Well, they’re four of my tenets I would say. First is finding God in all things. That means that God is not just confined to the walls of a church, or in scripture, or in personal prayer, but God can be found in your relationships, in work, in music, in your family. It’s a very broad-minded spirituality.

Second is this notion of being contemplative in action. Which means that most of us, and I would bet that most people who are listening to this podcast are pretty busy people. None of us are monks, or a few of us are monks. But can you have a contemplative stance in the world? Where you’re looking at things in a contemplative way. You’re not going, running from place to place without any sort of reflection. That’s another tenet.

Third, it’s incarnational. Which means that it trusts that God is present, and in terms of Jesus, that Jesus … God became human in Jesus. There’s a kind of comfort in that, and an ability to really connect with Jesus and connect with God. And then fourth, I would say it’s freedom. That’s a really important thing for a lot of people these days. Freedom and detachment.

For a lot of people who don’t know Ignitian spirituality, it’s very similar to Buddhism, the sense of detachment and freedom. You’re not so attached to something that you can’t respond to God’s will. Funny enough, I think if I were to do it again I’d just say three tenets, because the incarnation and finding God in all things are close. But hey, you know, my book’s not perfect.

Brett McKay: Right. The freedom and detachment, we’ll talk a little bit about that later, reminded me of stoicism too in a lot of ways.

Fr. Martin: A little bit. I think the difference between Ignatian spirituality, or more broadly Christian spirituality, and stoicism, is that it has an object. The freedom is freedom for something. The freedom for is responding to God’s voice in your life. Whereas stoicism, I think it’s less, I mean from what I remember about my philosophy courses, it’s not connected to God per se. But there are many overlaps between Ignatian spirituality, and you read Marcus Aurelius and it’s very similar.

Brett McKay: This book you wrote, The Jesuit’s Guide to Almost Everything, you’re coming at it from a Catholic perspective, from your background as a Jesuit. But what’s interesting, I’ve been reading the reviews about it, that people of all faiths and backgrounds, and even people who aren’t religious or don’t even believe in God, they’ve gotten something out of it. What do you think it is about the principles of Ignatian spirituality that makes it so attractive or useful to people from all walks of life?

Fr. Martin: For one thing, Ignatius himself dealt with people from all walks of life. It was someone who was just dealing with people in a monastery or sisters. He dealt with people who were, during the sixteenth century, working and politicians, and even royalty, so he wanted to make it accessible. But really, it’s that finding God in all things that I think really appeals to people, and even people who are seeking and agnostic or atheists. There’s a sense that Ignatian spirituality meets people where they are, which is what I try to do in the book.

But even if you don’t believe in God, I have plenty of friends who are agnostic and atheist, I think they like the idea of freedom. I think they like the idea of being able to, for example, review your day in a prayer called the examen, or the examination of conscience. There’s a lot, there’s a whole chapter on decision making, which is very helpful for a lot of people. I wrote it for everybody basically. Obviously as a Jesuit I want people to come to God and move closer to Jesus, but I recognize that that is not where everybody is at the moment.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about some of these practices. You mentioned the examination of conscience, or the examen. What is the purpose of this exercise? What are the steps? How can it be modified for people depending on their spiritual background, or lack of it?

Fr. Martin: Sure. The examen is basically a prayer that helps you review the day and see where God is active. I think if you’re not religious it could probably function as a review and kind of self-examination, which is certainly valuable. But it really, I think to be fully appreciated, needs to be understood in the context of our relationship to God.

What is it? Basically you start off with placing yourself in God’s presence. You would do this maybe at the end of the day for 15 minutes. By the way, if you go online, we have Examen Podcast at America to help lead people through it. . . easier if you’re being led through it. Anyway, you put yourself in God’s presence. Remember that it’s not just you plowing through the day, remembering things.

Second, you call to mind anything you’re grateful for. You call it mind. St Ignatius says you savor it, almost like you’re savoring a good meal or a fine wine. That could be big things. You got a promotion, you got engaged, bought a new car, something like that. Or it could be small things. You heard from a friend of yours that you hadn’t heard from for a while. You went out with a friend for a beer. Your favorite sports team won the world series, the Super Bowl, as mine did recently. You savor these things and give thanks to God. You just, “Thanks for a great thing happening today.”

The reason you do that is because we are generally problem solvers, and we move on to the problems very quickly. Ignatius wants to ground you. The next step is you review the day start to finish. You try to see where God has been active. Where did you notice God’s presence? Where was God active? Where did you turn away from God? That leads you to sorrow for your sins, your limitations. There’s a sense of being open about your limitations, and your failings, and your sinfulness.

And then, last stage is you ask for the grace to see God in the next day. It’s a very simple prayer. It takes about 15 minutes at the end of the day, which is when most people like to do it. But it really gets your spiritual house in order, because I think it’s a lot easier to see where God was than to see where God is frankly.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that’s interesting. As I was reading that, I thought it was … St Ignatius was sort of ahead of his time. You see psychology, positive psychology saying, because giving people like, “You should do this,” like show that you’re … Think about what you’re grateful for, review on how you can improve yourself and et cetera, et cetera.

Fr. Martin: Yeah. No, he is a brilliant psychologist frankly. He understands how the human mind works. Not only from going through tough times in his own life, but really counseling other people. He’s also great at helping people sort through where different feelings are coming from, and what’s leading you to something healthy, and what’s leading to something unhealthy. He really is, he is a master psychologist. I found that Ignatian spirituality has really … That’s an understatement, has really not only changed my life, but helped as a human being live a happier life and a more fulfilling life. Those are some of the things I wanted to communicate in the book to everybody.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Speaking of St Ignatius as this psychologist, he devotes a lot of time to desires and thinking about your desires. What’s going on there? He says you should pay attention to your desires. What does he mean by that? Because when I think, I think when most people hear desire they think, “I desire food. I desire sex. I desire all these other things that aren’t that great.” So what is he talking about when he’s talking about desire?

Fr. Martin: Yeah. Although I should say, there’s nothing wrong with food and sex and clothing and things like that. I think what he’s talking about are the deep desires that lead us to know what God wants for us. It’s a very basic thing. How does God call us to things? If you want to talk about say something like marriage or falling in love, God calls us through physical attraction, spiritual attraction, emotional attraction. Most people who are religious and are married or in love would say, “You know, I think God called us together.” That’s how it works.

God calls us to our different vocations through what we’re interested in. You desired to start this podcast. There’s a reason that you’re excited about it, that you’re interested in it. This is one way that God calls us to do the things we’re meant to do. And then on a more fundamental level, God calls us through our desires to be the kinds of people we’re meant to be.

I bet most of the people listening have a desire or an image in their minds of the person that they want to become. Like, more loving, move charitable, more relaxed, freer, less bothered by things. I would say that that image and that desire is one way that God calls us to be that kind of person. How else would God work?

There’s a sense that if you pay attention to your desires, and your deepest desires, and you can discern which are surface desire, like, “I want a new PC,” and which are the deep desires that really can help you move towards the person that God wants you to be. It’s very freeing. I think people have been told for so long not to pay attention to their desires, that they when they hear this it clicks, makes sense.

Brett McKay: What do you do about those, you talk about those higher level desires, of being charitable for example? You might desire that, but then you don’t desire to do the things that you have to do to be charitable. How do you learn to want, to want that thing that you know is good for you?

Fr. Martin: What a great question. That’s exactly what St Paul said. He said, “I don’t do the good that I want to do. I do the bad that I don’t want to do.” Yeah, I think first of all by recognizing that it is a call. That’s it’s not simply, “I have this interesting feeling to help that homeless guy.” That it is in fact coming from God, and that God’s going to help you. If you decide that you want to live a more charitable, or peaceful, or loving life, this feeling that that’s what’s being asked of you. To remember that, first of all that’s a call, so to reverence it in that way. It’s not just some fleeting feeling you have.

Second, that God’s going to help you. Why wouldn’t God want to help you to live more charitably? And frankly, third, that it might take some time before it feels natural. Fake until you make it. It may feel strange to start to be forgiving and let go of grudges and be more charitable, but that’s okay, because to trust that God is on your side and that God knows what’s best for you.

I often use the example of, this usually helps people, if you have some injury and you go to a physical therapist, and the PT guy says, “All right, what I want you to do is walk around on your foot in particular way.” At the beginning it might feel painful, but you trust the guy because he’s a PT guy. You will continue to do it because you trust it, you know it’s good for you, and you know that this guy has the best in mind for you. That’s the idea, that you follow these desires because you know where they’re coming from and you know that they’re going to lead your good, and everybody else’s good for that matter too.

Brett McKay: Another thing you talked about related to desires is this idea of disordered attachments. What are those, and how do they mess up people’s lives?

Fr. Martin: What Ignatius calls, it’s kind of a strange phrase, what Ignatius calls a disordered attachment, or you can also say an unfreedom, is anything that keeps you from becoming the person you want to be, or the person that God wants you to be and responding to God’s will in your life. For example, if you’re so attached to something that you can’t be a loving person, then it’s disordered.

The best example is, let’s say you’re in the hospital and you’re a good friend of mine, and I want to visit you. But I say to myself, “Oh my gosh, if I go to the hospital I’m going to get sick, because there’s all these sick people in the hospital.” Ignatius would say, “You are so attached to your own health, or your own desire for perfect health, that it’s disordered.” It’s actually preventing you from being a good friend, from being a good human being. He would say, “You need to really look at that, and you need to free yourself of those disordered attachments.” We all have them. We all have those unfreedoms in our life.

If you’re so attached to status, and power, and money, that you can’t be a good person, then that is a disordered attachment, and you need to let go of it. It’s hard to do but it’s essential.

Brett McKay: There’s that Buddhist sort of connection there a bit.

Fr. Martin: Yeah, sure. This sense of being free and not being tied down.

Brett McKay: Did Ignatius have any practices to help you, I don’t know, get over these disordered attachments, or do the things you know you should do? Did he have any mental or spiritual exercises he suggested?

Fr. Martin: He did. One of them is called agere contra. Agere means to act, and contra is obviously against. He means to start doing it even though it feels like it’s unnatural, to act against your natural for example selfish desire. For example, when I was a Jesuit novice I was very concerned with my health. I said to my novice director, “The last thing I want to do for my ministry is work in the hospital.” He said, “Why not?” I said, “Well, I don’t want to get sick, and kind of grossed out around people who are sick and all the sights and smells and sounds.” He said, “Good. You’ll be working in a hospital.”

That wasn’t to punish me. That wasn’t to make me feel bad about myself or to put me in my place. It was agere contra. It was to act against your natural inclination in order to free yourself up. When I went in and spent, gee, a couple months there, working in a hospital for seriously ill patients, this was in Cambridge, Mass, it did. It freed me of that. And also, what kind of a Jesuit priest would you be if you could never go into a hospital.

That’s agere contra. That’s working against or acting against your natural desire or your natural inclination, if it’s an unhealthy inclination or desire. The unhealthy inclination was to only care for my own health.

Brett McKay:I think this was your, I don’t know if this was Ignatius, but one that really hit home to me was, act like your best self would.

Fr. Martin: Yeah. That’s actually my addition to Ignatius. I like to say to people, “Imagine,” and this is also a good decision making tool, “Imagine the person that you really want to become.” I think we all, as I mentioned earlier, we all have an idea of the person we’d like to be in five years, 10 years. This is specially true for young people. If you’re right out of college, you know, “Okay. This is the kind of person I want to be.” Or you see someone, you say, “Boy, I’d like to be like that guy. He’s so kind and he’s so nice and he’s so confident,” whatever.

The trick, I think, is to say to yourself, “All right, in this particular situation in this decision making time, what would my best self do.” It’s very clarifying. Can I give you an example?

Brett McKay: Yeah, please.

Fr. Martin: A good of friend mine’s father died a few years ago. A very good friend of mine, a Jesuit. The funeral was in upstate New York, in Buffalo as I recall. I was very busy and there was this snow storm coming. It was really a tough week and I didn’t quite know what to do. It was very hard for me to figure out the right thing to do. On one hand I had work, on the other hand I had all sorts of desires to be with my friend.

In any event, I went back and forth, “What’s the right thing to do?” Finally, I used that tool. I said to myself, “What would my best self do?” I tell you, within a second I realized, “He’d go.” My best self, I want to be would go to his friend’s father’s funeral. No question. Just like that, it came. And so I did, and I was very happy I did. So, what would your best self do? And do it.

Brett McKay: What I like about that is that it gets, it makes … There’s that whole fake it till you make it, and people feel phony. But thinking about what your best self would do sort of reduces that cognitive dissonance, because you’d be like, “This is me. This is what I want. This is what I would do.”

Fr. Martin: That’s exactly right. It’s okay to feel like it’s unnatural. Of course it’s going to feel unnatural if you’ve been acting a particular way and you’re changing your life. It’s like going to the gym for the first time. If you’ve never been it’s going to feel odd. You’re going to feel funny in those clothes and maybe self-conscious, but eventually it will kick in and you’ll feel comfortable there. I think the fact that it feels unnatural is not a reason not to do it. It’s okay to admit that and to say, “I’m trying something new, but I know that this is going to help.”

Brett McKay: One of the things Jesuits do, like a lot of other orders, is they take a vow of poverty. Why is that? What’s the purpose of that?

Fr. Martin: Well, the real purpose of the vows, which is poverty, chastity, obedience, is to follow Jesus. Jesus lived poor, we know that, chaste, he didn’t get married, and obedient to the Father’s will. That’s the main reason, but it also is very freeing. I don’t own anything. Everything I get from my books and salary, I work at a Catholic magazine, goes to my Jesuit community. It’s very freeing. I don’t have to worry about my next job, even if you call it that. We have ministries in the Jesuits. It’s just great. I love it.

The Society of Jesus, the Jesuits, take care of me. As we say, “Three hots and a cot.” Anything that I would need in terms of clothes and things like that. But that is for me the easiest vow. When I worked at GE I was doing pretty well. I was making a good salary. I had a lot of suits and a lot of stuff, and a car. I love not having a lot of things. I really do. A friend of mine came into my room the other and said, I have books and clothes and stuff, obviously, he said, “Where’s all the rest of your stuff?” I said, “That’s it.” It’s great. You feel very light. It’s also a way to identify with the poor. We don’t live like homeless people, but we live very simply and we try to identify with people who are poor. Which is what Jesus did, he tried to live simply. His primary audience was the poor.

Brett McKay: How can ordinary people live this idea of poverty or simplicity without having to become a monk or whatever?

Fr. Martin: Sure. Yeah, most people aren’t going to become monks. By trying to live simply and looking at what you have with a critical eye, and saying, “Do I really need this?” At GE, of all places to learn spiritual advice, we used to talk about nice to have and need to have. How many sweaters do you need? How many sneakers do you need? Do you really need all that stuff? Can you get rid of them?

People always feel better when they do spring cleaning, when they get rid of a lot of crap. And then, to also say that it’s better to give it to the poor. One of the great lines from a Catholic, St Francis de Sales I think said, “That extra coat in your closet doesn’t belong to you, it belongs to the poor.” So there’s also a sense of giving away not only for your own sense of freedom, but for the poor.

Brett McKay: Going back to this idea, one of the big overarching themes in Ignitian spirituality is moderation. It seems like he was not keen on taking poverty to the extreme.

Fr. Martin: No, he wasn’t. He learned that early on in his life, when we mentioned his attention to his appearance. At once point he let his hair grow long, he let his fingernails grow long. He said, “I’m not going to take care of my health. I’m not going to eat well. I’m going to eat like a hermit.” It really screwed up with his health, or screwed up his health, and he realized that that’s not going to help him work. He needed to have a certain amount of health.

So he tried to have things in moderation. The Jesuits, we don’t live like homeless people, we don’t live like hermits. We have houses. We have beds and clothes and food, and things like that, in order to help us do our work. It’s a very practical spirituality. Now that might be different than Francis of Assisi, who did live extremely simply and didn’t want his brothers to have even a house. But for Ignatius, his way of discerning was that if we just try to live simply and do things in moderation, it’s a lot better for helping us do our work.

Brett McKay: Ignatius also had a lot to say about not just our relationship to God, but also about our relationship to other people. Can you talk about that, because I think that was the most interesting and probably useful things I got out of the book was our friendships and relationships.

Fr. Martin: Yeah, thanks. We, Jesuit, take a vow of chastity. Which means we don’t get married, we don’t have sex, we don’t have what we call exclusive relationships. That means that it’s a different way of loving. It’s a way of loving people deeply but also freely. A lot of it relies on friendships, very deep friendships. I talk in the book about the value of having close friends and what it means to be a good friend, and what it means to celebrate your friendship.

The way of chastity and the way of St Ignatius is not about being in your room all night and staring at the TV because you don’t have anyone in your life. It’s about celebrating your friends and really loving them deeply, and seeing in that love an expression of God’s love. That too can be very freeing. I often tell people I certainly miss one-on-one intimacy, and sex, and exclusivity in that way, but I have a ton of friends. This is not better or worse, I just simply have more time for them than people who are married. I just do. That would make sense I think to most people.

So, to have these great friends who you can love freely and deeply is really a blessing. I think part of the book is to remind people of the value of friendships, even people who are married. This is not just for single people or celibate or chaste people. It’s for people who are married too, because we tend to overlook that. We tend to overlook the value of friendship and that kind of love in our society.

Brett McKay: One overarching principle for friendship and all relationships that Ignatius taught was something called the presupposition. What is that principle? How can it improve relationships?

Fr. Martin: Yeah, that can improve … I think it can improve our country too, especially right now. The presupposition is something that he began what’s called his Spiritual Exercises with, which is his great manual on prayer. He said basically it’s giving people the benefit of the doubt. If someone says something that you don’t understand or don’t agree with, you ask them what they mean by it. If you still don’t understand, you give them the benefit of the doubt. You presume that the person is trying to act on his or her best interests, and you don’t critic them without listening to them.

And you know, boy, just go on social media, or Twitter, or Facebook, or even Instagram, and you can see people not giving one another the benefit of the doubt. Always taking someone’s words and twisting them, or assuming the worst. It’s interesting that, for me at least, that that is the beginning of his classic text on the spiritual life. Which is, it’s not some footnote. That is front and center. Give people the benefit of the doubt. As we say in the Jesuits, “Give them the plus sign.”

It frees you up from a lot of grudges, and resentment, and ridiculous anger that has nothing to do with the reality of the situation. It’s just your interpretation of it. It frees the other person. It lets them be who they are. I find that really helpful. So yeah, the presupposition is key for Ignatian spirituality. I wish more people in our political system used it too.

Brett McKay: Yeah. No, that one hit home hard for me because I often … because it’s so easy to do when someone, like a friend say snobs or you forgets you. You think, “What a jerk. He’s so thoughtless.” And then you think, “Well no, he’s probably really busy. He’s got something going on in his life.” Assume that instead of assuming the worst.

Fr. Martin: Exactly. They usually do, that’s the irony. When you dig a little deeper you find that people who are in those situations do, are struggling. You know, that old thing about be kind to people, everybody is fighting their own battle. I’m sure you’ve heard that expression, there’s a little of that. If someone snaps at you or shoves in front of you on the subway, I live in New York, can you say, “Boy, this person … maybe they’re rushing to visit their husband in the hospital.”

Instead of punching them in the face or wanting them to die, you say a prayer for that person. It’s a much better way to live, and it really frees you of a lot of really unnecessary anger. Now that’s not to say that people aren’t intentionally mean to us from time to time, but most of the time it’s not intentional and it’s good to give them the plus sign, as we say.

Brett McKay: Going back to that idea of being disappointed in our friends for not being better friends for X, Y, or Z reason, what do think, or what does Ignatius think is really behind these disappointments? Is it because we’re thinking of people as things, that they’re their to satisfy us, and our needs, and our desires?

Fr. Martin: I think that’s part of it, that we look at people as functional and they should be satisfying our desires. There’s a sense of, I’d say not all the time, but there can be a sense of selfishness that, “I need to be at the center of everybody’s life.” And there’s also a sense of proportion, that not everybody can always be attentive to you, and can always be at your beck and call. It’s loving your friends as they are.

I’ll tell you a funny story. One of my best friends is terrible at keeping in touch, just absolutely awful. I mean, I’ll text him and he’ll be like, “Yes. No.” I asked him once, he said, “I don’t like texting. I don’t like talking on the phone a whole lot. I love being together.” We take vacation together and we have tons of fun when we’re together. What’s the point of this long story? The point is, I need to let my friend be who he is. Right? I need to love him as he is, not as I would want him to be. You know, the person who calls me every week religiously, or text me.

We’ve talked about it. I said, “You know what … ” He said, “That’s just the way I am. I don’t like going on the phone. I don’t like … I never have, ever since I was little.” That’s who he is, so can I love him like that and not demand that he be the kind of friend that I want or think I need. Boy, I tell you, once you free yourself of that, you free yourself of the desire to make people in your own image, your life is a lot more pleasant.

Brett McKay: What does St Ignatius say about keeping friendships and nurturing them when we’re so busy and mobile? You’re not married, so you have more time for friends, but you’re also very busy, so you’re doing lots of stuff. What are your insights about that?

Fr. Martin: It takes work. I think that’s one of the most important things. They don’t just happen. I mean, friendships develop organically, but to keep them alive, it’s like a garden. You have to water them, and nourish them, and nurture them. That means time with people, and attention, and sacrificing your time, and really wanting the best for them.

I think it’s really important to say that even with distance it requires some energy and some effort, but it’s worth it. Ignatius says an expression called union of hearts and minds. That the Jesuits, especially early on, when there were few of them and they were all over the globe, people like St Francis Xavier, who was in India, in Africa, in Chine. They kept in touch with letters. That was the way that they did it back then.

Now, you can talk about obviously email and text and things like that, but it requires one-on-one time. It requires face time, and that’s an investment in friendship. We invest in our jobs and in our career. We would say, “Of course, I’ll take this time out to get an MBA, or work over time, because my career is really important to me.” Which is true, and great. Or, “I will sacrifice myself for my family.” Well, it’s also, you need to in a sense do the same kinds of things for relationships in your life, and friendships in your life, or you’ll find, since we’re talking about the art of manliness, like a lot of guys who are out of school for a couple of years and married, their friendships atrophy. I’m sure you know that.

A lot of my guy friends say, “How are you able to keep up?” One reason is I’m not married, but another reason is I really, I’m very attentive to that. I really spend time … Basically calling them from time to time and just keeping up. That is a great, I’m sure you know that is a great sadness among a lot of married men, that they don’t … And so that’s a real insight from Ignatius, union of hearts and minds and really spending time on it.

Brett McKay: There’s a practice you mentioned that Jesuits use to build friendship, called faith sharing. What is that?

Fr. Martin: Yeah, it’s pretty great. We get together, depends on the group of guys, with my friends once a month, and you talk about where God has been active in your daily life and in your prayer. Now, not everybody is going to be able to do it in that way, because they might not be religious or have religious friends, but can you get together with your guy friends, or if you’re … female friends, it doesn’t have to be just guys, and talk about things that I like to say are meaningful, significant, or important. That’s a nice way to start off. What’s meaningful, significant, or important that’s happened over the last month or couple weeks?

It’s really wonderful because not only from a religious point of view do you see how God is at work in each person’s life, but it really helps to in a sense be compassionate to your friend. Let’s take an example. Let’s say you have a group of three or four guy friends who get together, and one guy has been out of touch or has been a little distant, or aloof, and you don’t really share with him on any sort of deep level, or you haven’t for a while. When he sits and says, “You know, I have to tell you, my father’s going through a cancer treatment,” or, “I’m really struggling at my job,” you have this sense of understanding him better, such that you can be a better friend to him.

That doesn’t have to happen in a group but we find it’s really helpful when it does happen in a group, because there’s something about a group dynamic that when a person shares what’s going on, and people can respond in a gentle way, it also helps the person feel really supported. So yeah, face sharing is really important for personal support, but from a religious point of view it also helps to see where God has been at work. When it’s hard to see God at work in your life, it’s easier to see where God is at work in the other guy’s life.

Brett McKay: I’m sure that’s hard for a lot of men to open up like that though too.

Fr. Martin: Yeah, it is. Although, it’s funny, it is and it isn’t. I was just on a pilgrimage to the holy land, just two weeks ago. We had 100 people, and they were religious of course. But a lot of the people who were on the trip, probably most of them, were very successful, fairly wealthy adult men. It was men and women, kind of a mix. You had captains of industry, to use that old fashion term, and when they got in a group and once one person opened up about the death of a child, an illness, divorce, it gave permission for the other guys to do it.

It gave permission for people to be themselves and for people to talk about their desires, and for people to talk about where God was in their lives. So I’d say yes and no. I think that if it’s done in a way that is … How would I say it? That’s inviting, I think people respond to it, because I think there’s a deep need and a deep desire for people to be known, and for people to be open and transparent. I really do. Would you agree? Don’t you think that deep down-

Brett McKay: Yeah, I would think so. Yeah. People want to be known. People want to be recognized.

Fr. Martin: Yeah, and I think it would be hard to do at a bar, but maybe in a different setting, where people feel more comfortable. By the way, that’s not to say that those kinds of sharing don’t happen at bars and places like that, but I think to provide a space where people feel safe can be a real blessing for people.

Brett McKay: Right, and like you said, it just takes one person. Going biblical, it’s like the leaven. One little bit can have a big effect.

Fr. Martin: Yeah, and truth begets truth. I think that, as they say, heart speaks to heart too. There’s a recognition that, “Wow, we’re all human.” I think that’s one the lessons I learned when I was out of college, that I think most of my college years were spent trying to be cool and looking like I was on top of everything. But once you’re out of college, for some people earlier, you realize that everybody’s struggling, everybody’s facing their own battles, and it’s okay. To be able to support one another means that the first step is to be honest with one another.

Brett McKay: You mentioned, we talked about the vow of poverty. You’ve hit on the vow of chastity. Another vow that you take is the vow of obedience, but that’s a virtue or an ideal that’s pretty unpopular with the general public. Because when . . .

Fr. Martin: Yeah, no kidding.

Brett McKay: . . . When you view obedient it means like you’re a dog, or it makes you think of Nazis, or whatever. How does obedience work in the order? How much say do Jesuits get as to where and what they are assigned to?

Fr. Martin: That’s a good question. I never of the Nazi analogy too, but that is a good negative view of obedience. It’s obedience to God basically. It’s trying to understand where God’s at work. One of way of looking at obedience I talk about in the book is my dad died in 2001 of cancer. When the diagnosis was given to him and to us and the family, I had a choice. I could be a complete jerk, and say, “Well, I’m not going to really engage this. I’m not going to enter into this.” Or I could be, this where the word comes in, I could be obedient to what God wants me to do. Which is to really be a good son, and to step onto that path, and as a friend of mine likes to say, “surrender to the future God has in store for you.” It’s that kind of obedience.

For the Jesuit, obedience is to your religious superiors who ask you to do certain jobs. The idea is that they would have … They’re the highest level to be the head of all the Jesuits in Rome, who has a better of what the needs of the church are than you do, me in my little office in New York. So if he were to say, “Jim, we need you to do this job.” The idea is that he has a better idea of where the greater needs are, and also that God’s leading him. It’s that kind of obedience too.

But really, it’s obedience to God. It’s obedience to what God wants. And yeah, it’s not a popular idea right now, but I think it’s necessary, because if you’re in a sense disobedient to what God wants, then it’s all about you. Let’s say, to use the example of my dad who died. Let’s say I were to say, “Yeah, I’m too busy to visit him.” That’s a kind of disobedience. That’s a kind of freedom that I don’t think would be very helpful.

I could see a lot of people do that, who’d say, “Well, I’ll leave it … I’m not doctor, so I can’t really help,” or, “Yeah, I don’t want get too sentimental because I don’t know if I could there,” or there’s there’s a withdrawal from those difficult situations that I think we all feel. We don’t want to do it, but that’s the obedience. That’s the heart of obedience, and that’s the kind of stuff I talk about in the book.

Brett McKay: What if let’s say your desires and the desires of your superiors conflict? Let’s say your superior says, “This is what we need you to do,” but you’re like, “No. I really feel like this is what I should be doing.” What happens there?

Fr. Martin: That happens fairly frequently, and usually with assignments. Let’s say, here I am, I work at America Magazine, a Catholic magazine. Let’s say my superior says, “You know Jim, you’ve been there 20 years now. It was a good run. Now we need you to be pastor of this church.” Now, he would say, “Go pray about it. See what comes up. See what your desires are and where God might be leading you and how you feel about that. What does that do to you inside?” Usually the Jesuit come back and say, “Yeah, okay. I think that makes sense, and I trust that you’re praying about this, and that you’ve got my best interest at heart, and that you’ve got the best interest of the world and of God’s people and the church at heart. So yeah, I’ll do it.”

Now, a lot of times, or maybe sometimes, the guy would say, “You know what, I’m not feeling that. Really, the last I want to do is be a pastor. I’m really not good at organizing. I’m terrible at whatever.” The superior might say, “Okay. Thanks for … That’s good. Maybe you’re right, and I hear that, so stay at America.” Or he might say, “Yeah. You know what? We really need you.” That’s where you would say, “Okay. I guess I’m going.”

The idea is, again, that he has a better understanding in mind. For a lot of people that seems like, “Oh my gosh, I could never do that.” But that’s what we do at work. I worked at GE for six years. Let me tell you, I had a hell of a lot less say at GE about what I was going to do day to day than in the Jesuits. I often talk about obedience and remind people who are in the corporate world, “What do you do? You’re obedient to your boss.” It’s often not a communal discernment as we say. But the ultimate obedience is really to God.

Brett McKay: Right. For a regular person, what does that look like? It’s following those, I don’t know, those compulsions of conscious to do the the right thing, is that what it is?

Fr. Martin: I think that’s part of it. I think the idea of surrendering to the future that God has in store is really important. I think obedience … It’s easy to be obedient when something’s easy. Let’s say you get a promotion, or you’re going to get married, or your wife’s going to have a baby, or whatever. The obedience is, “Wow, I’m going to enjoy the new job and say yes to it and really jump into it,” or, “I’m going to get married and I’m going to really love it.” There is an obedience there. There’s a kind of ascent to what’s going on. That’s important.

But the hard part is when it’s suffering, and that’s where the real obedience comes in. That’s really, I think, the answer to your question. Which is to say yes to those things, even those things that you think are going to be difficult, because you feel that this is the right thing to do. So the example of going to my friends’ father’s funeral, which was a small thing, but the big thing of really caring for my father and entering into that. Because I’m sure you know, there’s a way … Wouldn’t you agree there’s a way of standing at arm’s length from some of those things?

Brett McKay: Yeah, for sure.

Fr. Martin: Yeah. You can say, “I’m just not going engage. It’s not going to … ” I know guys like that. It’s just, “I’m just not going to enter into that.” The obedience is to say yes, to say yes to those things.

Brett McKay: And then that requires too to be detached from outcomes or whatever.

Fr. Martin: That is exactly right, or be detached from the need to … For example, I think one of the hard things about when my dad died, was I knew that … I mean, I’m not an idiot. I knew that it was going to be tremendously sad, and difficult, and frightening, and disappointing, and confusing, to watch him go through the treatment, and to help my mother, and to eventually prepare for the funeral.

Now, there’s a way, particularly with guys, that we can say no to that. We can say no to that reality, and distance ourselves, and close ourselves down. I know guys like this. They’re not letting it in. They’re not saying yes to it, and it’s on their terms. “All right, I’ll go to the funeral but I’m not going to see him at a hospital, or I’m going to go to the hospital, I’m just going to keep myself at arm’s length.” So you’re right.

The obedience is saying yes to those things and doing the right thing, and even, to your point, to say, “Even if it’s something that I need to let go off.” Like, my attachment might be to my own emotional equanimity. Like, I don’t like to cry, or I don’t like to feel out of control, or I don’t want to be upset. That’s a disordered attachment there. So I’m not going to let myself feel. See what I’m saying?

Brett McKay: Yeah. I got you.

Fr. Martin: Yeah, so that’s the attachment. The, “I don’t want to be emotional.” You have to let go of that in order to really enter into the situation where you will find God.

Brett McKay: Reverend Martin, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book?

Fr. Martin: Well, The Jesuit Guide to Almost Everything is, as they say, available anywhere books are sold. I also have a Facebook page under Father James Martin SJ, and I’m under Twitter and Instagram under JamesMartinSJ. Anywhere online, you can find information about the The Jesuit Guide.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well Father James Martin, thank you so much for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

Fr. Martin: My pleasure.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Father James Martin. He’s the author of the book, The Jesuit Guide to Almost Everything. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/jesuit, where you can find link to resources, where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to checkout the of the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoyed the show, I’d appreciate if you gave us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, and if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the podcast with a friend who you think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for your continued support, and until next time, this is Brett McKay, telling you to stay manly.