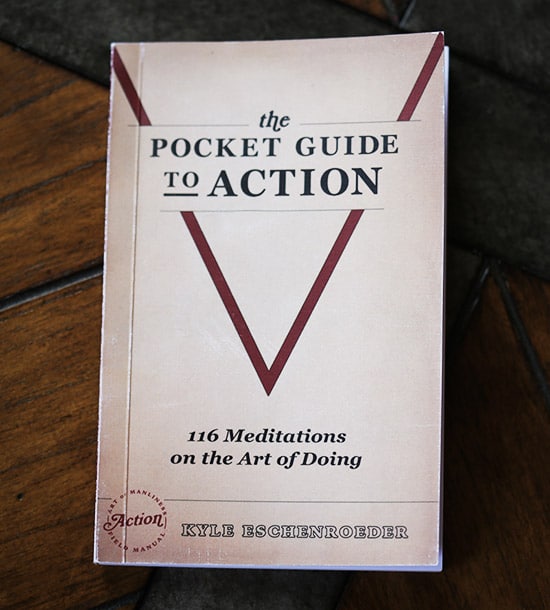

Last year, AoM contributor Kyle Eschenroeder published a piece on the site called “Meditations on the Wisdom of Action.“ It contained 116 short, punchy devotional-esque passages on the nature and importance of action. It was my favorite piece of content in 2016, and I still find myself continually thinking about its principles, and utilizing them in my life. The feedback we’ve received from readers has been similarly enthusiastic. At over 16,000 words, this longform article was about the length of a short book. So we decided to turn it into one, and titled it The Pocket Guide to Action: 116 Meditations on the Art of Doing.

Today on the show, I’ve brought Kyle on to dig deep into his philosophy on action. He shares why inaction can be expensive, how action can sometimes mean not doing anything, and why taking action is the best way to find courage and passion in life. Along the way, he shares tactics you can take today to help shift yourself into a more action-oriented mindset.

If you’ve been struggling to get started on a project or have just been feeling unmotivated, this podcast will light a fire under your rear!

Show Highlights

- Kyle’s posture towards action that runs counter-culture of the rah-rah motivation movement

- How Kyle came to formulate his philosophy of action

- How non-action can be action

- Why is inaction expensive?

- How do you get yourself to do the thing you need to do? How do you take the first step?

- The beauty of cold showers

- Balancing book learning with experiential learning

- Actions that have more leverage than others in setting you up for better future actions

- Creating habits towards action

- Why right action is proactive and not reactive

- Constraints you can set for yourself in order to focus on right actions

- Are probabilities useful to look at when deciding on whether or not to take action?

- Action’s magnetic effect

- The bad questions people ask that keep them from getting going

- The negative side effects that action can bring with it

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Meditations on the Wisdom of Action

- 10 Overlooked Truths About Action

- My podcast with Steven Pressfield about overcoming Resistance

- My podcast with Edward Slingerland about the idea of trying not to try

- The James Bond Shower: A Shot of Cold Water for Health and Vitality

- How to Create Habits That Stick

- Charlie Munger

- How to Hack the Habit Loop

- My podcast with Charles Duhigg about habits

- What Do You Want to Want?

- My podcast with Ian Bogost about setting up constraints for yourself

- The plugin that removes your Facebook news feed

- Ben Horowitz

- Edward Thorp

- Lessons in Manliness from Viktor Frankl

- Why Every Man Should Put Skin in the Game

- A Call for a New Strenuous Age

Yes, Art of Manliness published this book, but it’s a good one. Kyle’s insight about action is something that I find myself returning to again and again when I’m feeling a lag in my motivation. Pick up a copy in the AoM Store today. If you buy 3, you’ll get a free Take Action poster. If you buy 6, you’ll get free access to Kyle’s action course.

Connect With Kyle Eschenroeder

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Bouqs. Secure a Mother’s Day gift now, with Bouqs. Go to Bouqs.com and use promo code “Manliness†at checkout for 20% off your order.

ZipRecruiter. Find the best job candidates by posting your job on over 100+ of the top job recruitment sites with just a click at ZipRecruiter. Do it free by visiting ZipRecruiter.com/manliness.

Recorded on ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. Well, last year, Art of Manliness contributor Kyle Eschenroeder published a piece on the side called Meditations on the Wisdom of Action. It contained 116 short, punchy devotional-esque passages on the nature and importance of action. It was one of my favorite pieces of content in 2016, and I still find myself continually thinking about its principles and trying to utilize them in my life. The feedback we receive from readers has been similarly enthusiastic. At over 16,000 words, this long-form article was about the length of a short book, so we decided to turn it into one and self-publish it and call it The Pocket Guide to Action: 116 Meditations on the Art of Doing.

Today on the show, I’ve brought Kyle on to dig deep into his philosophy on action. He shares why inaction can be expensive, how action can sometimes mean not doing anything, and why taking action is the best way to find courage and passion in your life. Along the way, he shares tactics you can take today to help shift yourself into a more action-oriented mindset. If you’ve been struggling to get started on a project or just feeling unmotivated, this podcast will light a fire under your rear. After the show is over, make sure you check out the show notes at aom.is/action, where you can find links to resources where we delve into this topic, and you can buy a copy of our book The Pocket Guide to Action: 116 Meditations on the Art of Doing by Kyle Eschenroeder.

Kyle Eschenroeder, welcome back to the show.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Thanks for having me again, Brett.

Brett McKay: All right, so it was a few months ago you wrote an ebook-long treatise. I wasn’t a treatise; it was these pithy meditations full of just awesome actionable information. It was called The Meditations on the Wisdom of Action. You took these 116 or so ideas about action and fleshed it out, but here’s the thing, it was really popular. Got a lot of great feedback from it and some of the other content you’ve published on the site about not hacking your life. You’ve also written about action before, but this one you fleshed it out some more. What’s interesting about your take on action, it’s not this sort of rah-rah motivation Instagram meme, like ‘I’m going to take over the world’ type action. It’s more of a lens by which to see the world, a posture you take. It’s really a philosophical look at life where it revolves around action. How is action its own prism and philosophy?

Kyle Eschenroeder: Yeah, this is my probably my favorite question because a lot of people read it and they kind of take it as this, like you said, an exhortation, just me yelling about doing more stuff, take action, take action, take action, when, in fact, what it is is a description of action as closely as I could witness it. What happened is I consumed a ton of those rah-rah blog posts and books that are just yelling at you to take action, take action, just do it. It’s all just an extension of ‘just do it,’ but I got exhausted from that. That kind of stuff might get me pumped for a day, then it got exhausted and then eventually kind of embarrassing to me. Like you said, I wanted to actually look at the world’s true actions, see if it’s a worthwhile goal.

Where I started from is I took what happens when I take action, and I tried to look at it as closely as possible to understand it as closely as possible. After working through this for a while, the more I understood action, the easier it became to take more bold actions, take action more consistently, but then I think even more important, and what I was not expecting, was that I was more discerning in my action. When we talk about taking action, we’re not using a dictionary definition because that’s just everything we do, right? What we’re talking about is taking right action, doing the things we know we want to do but are held back by maybe Steven Pressfield’s resistance or some other kind of internal or external force pushing against us. You become more discerning in the actions you take when you understand the nature of action. When you understand the nature of action, it also becomes easy to take the actions you know you should.

That was a long way of getting to the core idea, which is the lens of taking action is essentially prioritizing reality over stories about reality. That is also prioritizing execution over explainable understandings of the world. An example of that is we can walk more efficiently when we’re not thinking about how we’re walking. If somebody says, “Wow, you’re walking funny,” you’re definitely going to start walking funny because you start trying to understand it. You start trying to consciously bring to your consciousness something that you do automatically really, really well.

The implications of prioritizing reality over our stories about reality mean that we put our relationship to reality ahead of measuring reality. We put what’s important to us over what others tell us should be important. We put predictions and commitments ahead of justifications and explanations. Actually, Nassim Taleb puts it really, really well. He says, “Suckers try to win arguments. Nonsuckers try to win.” Again, overall, the prism is that everything flows from prioritizing action over explanation.

Brett McKay: Got you. Read less blog posts, business books, and spend more time just doing stuff that you’re reading about.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Right. Yeah, exactly. If you read a how-to book, you’re going to feel like you’re learning how to do something when you probably would have learned more and gotten further if you actually tried doing that thing.

Brett McKay: Right. I thought it’s interesting, too, this definition you have of action. It’s not this typical definition. You argue in the article that action can also mean being passive sometimes, but passive in an active way, if that makes sense, deliberately being passive. That can be action, as well.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Right. Yeah. I think in the book I use the example of the Spartans. Spartan warriors were known for waiting for the other army to come charging at them, lose their composure, and basically start flailing around, things that we would traditionally see as action, when, in fact, they were just losing control of themselves, whereas the Spartans were waiting as an action. If we’re waiting out of fear or out of laziness, that’s inaction. That’s something that works against us, while waiting attentively, waiting for a certain moment, is one of the most powerful moments we can take.

A more modern example is Warren Buffett. He makes investment moves very, very rarely. He’s always waiting, always watching, always attentive to find the most powerful, most leveraged move he can make. He’s actively waiting. He’s not waiting because he’s fearful of the markets or he’s scared. He’s waiting to pounce, kind of thing.

Brett McKay: Right. Speaking of inaction, there’s a type of an inaction that can be productive, in the case of Warren Buffett or the Spartans, but there’s also an inaction you say that … You say inaction is expensive. Why is inaction expensive? Why don’t we often realize it’s the cost of not taking action?

Kyle Eschenroeder: This is, I think, another key. When we take action, the costs are immediate and obvious. The rejection we might face, the failure we might have to accept, the money we might lose, all those things are immediately painful and they’re very obvious to us, very measurable, while the benefits of action are delayed. The growth, the virility, the progress, the learning often come later. With inaction, it’s reversed. In action, costs or immediate benefits are delayed. With inaction, costs are delayed and benefits are immediate, benefits primarily being comfort. If we decide on inaction, we feel better right away and then later the costs come. Not only are the costs delayed, they’re also kind of hard to measure.

The costs of inaction tend to be decay, depression, and our life generally gets smaller. It’s hard to define, but we become smaller when we choose inaction too often. This plays great to a couple things, our need for instant gratification. We get the comfort right away, whereas action, we have to put in cost right away. It also plays to what gets measured gets managed. We can measure the costs of action. It’s very difficult to measure the costs of inaction, but they’re undeniable once they’ve had some time to compound. Your life is just, like you said, smaller, no virility. It’s the slow, gradual descent that makes it very difficult to see day-to-day, but year over year it’s painfully obvious.

Brett McKay: Right. Inaction, the benefits are immediate. That’s hard to get over, though. You have this line in your book … Just for people to know, we actually took Kyle’s thing he wrote … It’s not a post because it’s too long to be a post, but it’s like an ebook. We made it an actual book. We called it The Pocket Guide to Action. It’s available for pre-order. It’s fantastic. I love flipping through it. We’ll put a link in the site.

One of my favorite lines in The Pocket Guide to Action is this. It’s “I don’t feel like working out until I get my blood flowing. I’m too tired to have sex until we’ve begun. I don’t want to go to the party until I’m there. Motivation will follow you if you have the balls to go without them.” It’s true. I think we talked about this last time when you were on. We talked about action. The thing about action is that you usually don’t feel like doing the thing that you know you need to do until you start doing it.

That’s the question, though, is how do you bootstrap that. How do you get yourself to do the thing you know you need to do that you don’t feel like doing, but you know you’re going to start feel like doing it once you start doing it? How do you take that first step? I think that’s what holds a lot of people back. People know they need to work out, and they know once they start working out it’s not going to be so bad and they’re going to enjoy it, but they don’t feel like working out at that moment. Is it just brute force discipline, or do you have psychological ideas that can help you get over that hump or beat that resistance?

Kyle Eschenroeder: Yeah. I think there’s a million little tricks for this. I personally have to avoid relying on brute force discipline, just because I don’t feel like I’m incredibly disciplined. I mostly have to trick myself into doing something. Really, it’s whatever works for you. This is what I was saying. There’s a million blog posts out there, and they all give you a little trick to get going. I think just trusting in the quote that you just read, trusting that once you start, you’ll like it, you’ll gain momentum. I think knowing that … It take a little leap of faith each time, but just knowing that helps get the ball rolling. Probably the most consistently effective tactic that I use is to trick myself into minuscule steps towards the thing.

Something that I’m doing right now is getting back into cold showers, and it’s almost impossible for me to talk myself into getting into a cold shower because it’s just so uncomfortable right away. It immediately puts my body into shock. It’s not fun for the first 30 seconds at all. While my mind is running all of these negative things and making me flinch away from the water, I’m taking rebellious tiny steps in the direction that I decided on, which is cold showers. I’m turning on the water and I’m making it cold, I’m opening up the door, and each time I’m not committing to taking the shower; I’m just committing to a tiny step towards the thing. Then, finally, I’m there nude in front of a cold shower, and what am I going to do? Now I have to retreat. Now it takes more effort for me to turn on the hot water and I feel bad about myself. You get yourself set up so retreat feels bad.

Another example, going to the gym. If I’m just getting back into the habit of going to the gym, then I have to just put on my gym clothes or just show up at gym because once I’m there, I’m going to feel really guilty if I just walk in and walk out. I just commit to the tiniest, easiest possible thing that might have a chance of making me feel guilty for not doing the right thing. I think both of those things, working out and taking cold showers, once you do it, then you’re amazed that you ever had any kind of aversion to that thing. Of course, at the gym, you’re literally ripping your muscles apart, so it’s not pleasant if you’re not used to it, but once you get in the habit, then it feels great. My biggest trick is just lowering the bar so far that you can roll over it.

Brett McKay: Right. That’s a great point. We’ve had Ramit Sethi on the podcast. He talks a lot about breaking down your goals into micro steps. Tim Ferriss talked about when you’re trying to create a habit, if you’re having a hard time with it, you probably need to redesign it, how you’re approaching. That usually means making the habit smaller.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Yeah.

Brett McKay: A lot of great advice there. Okay, so you just said something when you were talking about action and your approach to action. You talked a lot about the importance of experiencing things firsthand; experience is the best teacher. I’m a big believer in that. I think the best way that I learn is when I get my hands dirty with something and mess up and learn from those mistakes, etc. At the same time … and I know you’ve read some Charlie Munger yourself. What I love about Charlie Munger is he’s a big believer in reading, and you read so you can learn from the mistakes of others. How do you balance that? How do you balance learning from experience, yet at the same time reading from and learning from the mistakes of others so you don’t commit those same mistakes?

Kyle Eschenroeder: Yeah, it’s so funny you mention Munger because when you said the question, the first thing that I thought of was a quote from Charlie Munger that he likes to repeat. By the way, I don’t know if you mentioned this, but Munger is Warren Buffett’s legendary investment partner that totally changed the way Buffett approached investing early on and allowed him to get as huge as he became. He has this thing that he’s been repeating for decades, and he says, “All I want to know is where I’m going to die, so I never go there.” That is some of the best advice you can get. Like you said, he’s looking for mistakes other people have made so he doesn’t have to make them.

I do think that we can avoid … Avoiding terrible things is the best way to a good life, more than anything positive. It’s this via negativa approach to a good life is if you avoid doing all of the terrible things people do to make life worse, you’re going to have a good life. At the same time, I believe that, to really grok something, to really understand something deeply, you have to experience it. I think what Munger is doing, and what we’re doing when we decide to avoid the mistakes of others, is we just decide that we don’t really need to understand everything. If I could’ve avoided touching a hot stove when I was a kid, my mom told me, and I trusted her, and I could’ve avoided it, I would’ve avoided getting burnt once, but I would never have a true understanding of why, what does it feel like to have your fingers burnt off. I think when we go with this, there are certain things that you don’t want to understand all the way.

There’s certain drugs that are so addictive, I don’t need to know the experience of having that drug because I know it’s going to end in a bad place. Now, that doesn’t mean I can have full empathy with people who have gone through addiction and suffered through these things, but I have a good-enough understanding that I need to move forward and to make decisions in my own life. We can avoid certain things, but I don’t even think … Certain mistakes have huge consequences. Other mistakes are completely avoidable, but the cost of making certain mistakes is worth making a mistake.

In my example, I used to trade money. I used to be a day trader. I used to run a small fund. When I made the transition from paper trading to trading real money, there was no … The theory was the same, and most of the practice was the same, but the psychological effects were completely different. I had to make a similar set of mistakes that I did with paper money with real money. I had to lose real money to really understand what trading method I needed to use. Then the same thing happened when I started trading other people’s money. First, I was trading mine. Then, when I started trading other people’s, again, same theory, but whole new set of mistakes psychologically that happened when you’re dealing with other people’s money. It’s a different texture of same mistakes, and you need to make those mistakes. You need to lose money, at least a little bit, in order to not lose a ton later on. Does that make sense …

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Kyle Eschenroeder: … in this context? Okay.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I think that makes sense. It’s about being smart about certain things. There’s some things you should just stay away from completely, but there’s some things that you need to figure out on your own because that’s the only way you’re going to learn. It’s basically taking an Aristotelian approach. Make the right mistakes for the right reason, the right time, that sort of moderation idea.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Exactly. Yeah, it’s like that Yogi Berra line “In theory, there’s no difference between theory and practice, but in practice there is.” You can have a great working map of your surroundings, but until you actually go and investigate the territory, you can’t fully understand what the map is saying.

Brett McKay: One of my favorite ideas you talk about in the book is that some actions have more leverage than others. What does it mean for a certain action to have extra leverage, and what are some examples of that?

Kyle Eschenroeder: I think even before we go into them, you say these are actions that should be prioritized. I consider leveraged actions to either automate or eliminate the need for future actions. A couple types of actions that automate actions are creating habits, the habit of working out, the habit of meditating. It’s something that you can do. It automates a habit. Another way is creating an environment. If you shape your environment in a way that shapes future actions, you’re essentially automating future actions.

An example of this I used recently is my girlfriend and I were eating out quite a lot just because we weren’t in the habit of cooking our own food for a while, so to ease us into cooking our own food, we subscribed to Blue Apron. Blue Apron, we’re paying for it, food is going to get here for the week. If we eat out too many times, then we’re going to waste a bunch of food that we already have in the fridge. That was a way of shaping our environment to shape and automate future actions.

Brett McKay: No, we’re fans of Blue Apron, too. By the way, they are-

Kyle Eschenroeder: Nice.

Brett McKay: They are a sponsor of the podcast.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Oh, I had no idea.

Brett McKay: Just so you know, Kyle was not paid to blurb this at all. It might just so happen …

Kyle Eschenroeder: No.

Brett McKay: … that they are one of the sponsors on this episode. Yeah, I love Blue Apron because, you’re right, it does create this habit of cooking when you don’t have it.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Right. Yeah. It makes it super easy. Then, for us, we were on it for two months and then started going to the store, and it was easy. It was easy to start cooking from total scratch. Those are two ways we can automate future actions. Then another great way to have a leveraged action is to eliminate future actions. You can do that with experiments. If you set up an experiment, then you’re paying attention to the results of a certain action or series of actions close enough that you’re going to minimize repetition. You won’t have to do the same or similar actions over and over again because you know that that’s not working. Another type of elimination would be hiring in a business. If you have a set of tasks or whatever, you can eliminate future actions by hiring.

Brett McKay: Right. No, it’s a very Aristotelian approach. Aristotle was all about you create habits … You not only want to be able to not have to think about doing the thing you’re wanting to do, but you want to make it even to get to the point where you enjoy it, right? You actually …

Kyle Eschenroeder: Yes.

Brett McKay: … enjoy doing the thing, and that takes work. It takes a lot of psychological, emotional, and mental, and sometimes physical, work to get to that point.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Amen. Yeah, but it’s interesting. Again, to me, that goes back to delayed … It’s what do you want up front and what do you want later. You want to want to do the hard thing, but in order to do that, you have to suffer through doing the hard thing when you don’t want to do it. You have to earn the right to want to do the hard thing.

Brett McKay: Another idea that I loved was that right action is not reactive, it’s proactive. I like this thought because it’s something I’ve thought about nearly every morning when I wake up and I look at my phone on my dresser and I think of checking it, and try to decide not to start the day in a reactive way where I’m reacting to my phone. What are some other ways that we set ourselves up for making reactive decisions, and why is that so detrimental to us?

Kyle Eschenroeder: I think the example you gave is so perfect for outlining this idea in total. If you think about it, you’re waking up, you’re reaching over to this … I don’t even know what … this source of information. You have no idea what you even want from it. You just want whatever is there. Then you open it up and you start scrolling through Twitter … I don’t know what your thing is … Instagram, Reddit. Mine are Reddit and Twitter. That’s where I go to. If my brain’s turned off and I just want to be fed random stuff, I go to Twitter, Reddit. You’re starting the day asking for the world to tell you what to think right now, essentially, instead of starting the day proactively doing the thing that you most need to get done today or thinking the thoughts that you most want to lead the day with. You’re going for a total crapshoot just by opening up your phone first thing in the morning.

I think, essentially, if we are taking a posture of action, part of that is being engaged enough with the thing that we’re doing to know whether or not that’s the thing we should be doing. If you have a priority, if you’re engaged in action, you’re automatically proactive, or at least will self-correct to being proactive. A couple very common examples of setting ourselves up for reactivity is checking your inbox with no purpose, or outside of a defined time frame. If you finish a task, if you know you have a task to do, but then you open up your inbox for some reason just to see what’s there, you’re asking for other people to demand your time. Again, super common. Nothing interesting here.

Another one is surfing the web with no aim. There’s a thousand companies that are A/B testing headlines to capture your attention, to, essentially, biologically force you to read their content and to trap you as long as they can with clickbait and whatever provocative headlines they have. You’re just setting yourself up for reactivity if you’re just going to go surf the web. Not that surfing the web is a terrible thing, we should just be conscious of, okay, I am submitting myself to these forces.

To me, the antidote for these things is just to ask myself what’s the best thing I can do right now. If I’m trying to get entertained and I want to spend time on Reddit, then I’m there, but I also should know that I’m setting myself up for reactivity. The opposite would be … The proactive use is I’m going to Reddit to get entertained or I’m reading this news story because I want to know this specific fact or if this specific thing is true. That’s a way of consuming as an act of action. It’s conscious. We’re engaged with it. It’s purposeful.

Brett McKay: One thing I’ve been thinking about, though, lately is that it’s hard … It takes a lot of mental bandwidth not to be reactive because it involves a lot of restraint. You see your phone. You want to grab it. You want to check it. You have to restrain yourself from checking your phone. You have to fight that urge. One thing I’ve been thinking a lot about lately, and it came into mind while you were talking, is a while back I had Ian Bogost on the podcast. I don’t know if you read his book Play Anything, but he had this idea about constraint versus restraint. He says we spend a lot of time restraining ourselves and it just backfires. We only have so much mental and emotional bandwidth in the day to say no to things, so instead of restraining ourselves, he argues for putting up constraints in our lives.

This goes along with what you were saying about shaping your environment to make action easier. He says instead of having to worry about restraining yourself, you offload that to your environment; you have these constraints you have to work within. That might mean you put some sort of blocker on your smartphone where you can only check certain apps at a certain time. You no longer have to think about restraining yourself. You have that constraint there. If you go to check your phone at not the right time, you can’t check your thing. It’s amazing when I do that, whenever I put constraints in my life, how much smoother things go, how much more I get done, compared to when I’m constantly trying to restrain myself from being reactive.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Oh yeah. Amen. Actually, I really like that podcast you had with Ian. It was a really fun conversation. Totally. I guess I should’ve mentioned that when I’m on Reddit, I also have StayFocused running, which is a program that I have set for 20 minutes a day. I have 20 minutes between Twitter and Reddit each day that I can scroll through and then it blocks me automatically. I used to have Facebook blocked, but I can’t because of business, so I removed my timeline. The distracting part of Facebook is seeing all the stories in the center. I don’t have that there anymore. Shaping-

Brett McKay: How do you do that?

Kyle Eschenroeder: It’s this app called … I can give you a link.

Brett McKay: Okay. I bet people would like to see that.

Kyle Eschenroeder: It’s just a plugin for Chrome. Yeah, man, it’s so good because you don’t see … The people that you actually care about, you hear about their life news in texts or emails, or through another friend or family member, but most of the stuff on Facebook, especially around election time and with politics as it is now, it’s not informative and really it makes you lose respect for a lot of the people you like.

Brett McKay: I had been off Facebook for a long time and I got back on for a reason. I needed to check something. Something was going on with a buddy. I got on the timeline and I was like, “Boy …” These are people, when I’m around them normally, these are great people, but you see the stuff they post, you’re like, “Man, I don’t know if I like you people anymore.”

Kyle Eschenroeder: Yeah, completely.

Brett McKay: I want to like these people because they’re good people. No, I hear you on that.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Yeah, absolutely. I’m 100% about shaping environments first before I even try to exert my willpower because I think my level of willpower is even lower than most.

Brett McKay: Yeah. All right, so let’s talk about this. You talk a little bit about this in the meditations on action. It’s about probabilities. A lot of people, the reason why they don’t take action, or they think they’re taking action but they really aren’t taking action, is they sit down, they plan things out, and they try to think of all the contingencies that could happen, the chances of these different contingencies happening. They’re basically trying to figure out how probable is success going to be, and if the probability is high, then they will take action. Do you think probabilities are useful to look at when deciding whether or not to take action?

Kyle Eschenroeder: This is a really good question, and I think statistics are getting more and more attention in the mainstream, which is I think really good, but as a general rule, we are terrible at predicting just about anything. The best mathematicians, the smartest people in the world, created systems that gave us probabilities that enabled actions that created the 2008 crisis, at least in part. There were incentives created primarily by bad probabilities. In our personal lives, we’re really, really bad at knowing the probability of something, especially the probability of success, because there’s so many factors in success.

To answer your question more directly, I think there’s certain domains in which probabilities are really useful. In health, for instance, if there is just overwhelming evidence that says cigarettes will cause health issues, then you shouldn’t probably smoke cigarettes. There’s just a lot of evidence that’s like 2% of people might live to 100 and smoke a cigarette every day, but 98% chance you’re going to fail your body by smoking a cigarette. There’s also studies that say that 80% of restaurants fail within the first five years. That does not mean that if you start a restaurant, you have an 80% chance of failing because that is taking all restaurants into consideration.

We don’t know what the economy was like at the time. We don’t know anything about the people that started. I mean, restaurants tend to be started … There’s a lot of people that just think it would be this ideal life and would be easy and fun to have a café. When the reality of actually running a restaurant hits them, they fold. It’s taking into account just all sorts of things. That statistic knows nothing about your network, your skills, your level of grit, and the current economic situation. You may have an 80% chance of succeeding if you start a restaurant.

Peter Thiel is a Silicon Valley investor, started PayPal, just very smart guy in most fronts, and he has this saying that is aimed at entrepreneurs. He says you are not a lottery ticket. You don’t start a business and then, once it’s started, you have X percent chance of winning. You have a million decisions to make every day. You have decisions about how much energy you invest, how safe you play it, how hard you hustle for sales. You’re never going to have a good probability. There’s also another investor and ex-startup guy named Ben Horowitz, one of the co-founders of a16z, Andreessen Horowitz, a big venture capital fund, has a saying. He basically says, as a startup founder, your job is the same whether you have 100% chance of success or a 1 in 1,000 percent chance of success. You have to find the path to winning. It doesn’t matter your chance at success.

An example that I think brings these two uses of probability together is shown in Edward Thorp. This is a guy who … he’s run hedge funds for 20 years, but he got really famous for being the first guy to really … He wrote the book Beat the Dealer, which is what inspired 21, all these blackjack movies and books. He used probabilities to beat the casino. He used statistics and learning about probability to learn how to beat the house in the actual game of blackjack, but then in deciding his path and deciding whether or not he should try to beat the house in blackjack, he could not use probabilities because everybody thought it was impossible. This was in 1950s, early 1960s. Everybody told him it was impossible to beat the casino because, otherwise, why would they exist? Why would they be so profitable? He didn’t even know his chance of success. He didn’t consider the probability that he could beat blackjack, but he used probability to beat the house.

Brett McKay: I love that, but particularly like the Peter Thiel quote, that you’re not a lottery ticket.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Yeah. Right?

Brett McKay: It’s empowering.

Kyle Eschenroeder: The sense of probability … Yeah, exactly. Exactly. I think what you were really getting at with the question is people use probability to rob themselves of agency in this world. They use a statistic as a reason to not try, and that is, in every case, bologna.

Brett McKay: You heard it here. It’s bologna. Okay. You also talk about action has a magnetic effect. It creates things like passion and courage. Once you start taking action, you start building this momentum. You even say it attracts forces bigger than ourselves. This sounds very much like Steven Pressfield territory. Can you tell a little bit more about what you mean by action creating this magnetic effect?

Kyle Eschenroeder: Absolutely. I think the whole action book, The Pocket Guide to Action, was really inspired by Pressfield, and some other people. Especially the format of the book, I almost see it now as the positive to his resistance. Steven Pressfield wrote in War of Art about the resistance, describing it, and, to me, action is focusing on the thing that overcomes it every time, not saying that this is on the same level as Pressfield, but this idea, yeah, absolutely. I think it is at the end of War of Art he talks about how action essentially calls down the assistance of angels and mysterious creative forces.

To me, you witness it. It’s the same idea that my mom was talking about when I was a kid when she said God helps those who help themselves, when people say the more I work, the more lucky I become. I think a big piece of this is that people respect those who take action and so are willing to help more often. If you’re confidently taking action, or if you’re just consistently taking action with a certain aim and you show grit, people will eventually begin to help you. A lot of times, these are the unseen forces. It’s just people that saw you trying, who you didn’t know saw you, who later show up with assistance.

Another thing that feels magic, but maybe isn’t, is that action allows for emergence of new perspectives. In an article, I use the example of walking in New York City. You’re walking down this grid of skyscrapers, and around each corner something new emerges and there’s a pattern. You go past one building; you look to the left; there’s just a bunch more buildings. Then, eventually, you walk past the skyscraper, you look to the left, and then you see trees. You see Central Park. You see nature. Up until that, the previous 90 blocks of walking, you should be able to extrapolate out from that and predict, “Okay, I’m just going to walk through skyscrapers the rest of my life,” but, no, now there’s this whole new potential.

The same thing happens when we’re taking action. There is a possibility when we take action for an entire new perspective, for an entire new piece of knowledge that helps us move to the next level in a way that was impossible for us before because we just saw the world differently or we’re missing this one piece of information. To me, those are just two examples of hidden benefits that happen when we take action that feel like they’re coming from the outside. They feel like it’s something bigger than us. That’s just me playing it safe.

There’s a lot of things … Anybody who has really gone for it, really committed to something, taking consistent action after it, has noticed new powers within themselves, inner commitment. Action is proof to yourself that you are willing to do what it takes. A lot of the self-defeating pieces of yourself fall away when you prove through action to yourself that you’re going to keep moving. That also feels like the sky is opening up, the angels coming to assist you, because parts of yourself that were not engaged before now are. It can absolutely feel like magic.

Brett McKay: That’s awesome. Going back to things that keep people from taking action … you talk about probabilities, using statistics to stop taking action … you argue in the book that another thing people do that prevents them from taking action is asking questions, particularly bad questions, the time wasters that keep them from getting going and actually doing something. What are some of these bad questions people waste their time on?

Kyle Eschenroeder: These are all based … We’re taught that if there’s a question, then there’s an answer. That may be true, but there’s certain questions that I think break logic or that we expect too much from. The four bad questions that I pose in the book belong to that category, the first one being “Am I happy?” I think happiness is something that is usually had obliquely. It’s something that follows when we’re taking action in a certain way. It’s not something that we can look at, identify, and say, “Okay, yeah, I’ve got it.” I think that is a bad question that ends badly for most people.

Another one that is answerable for a few people, but I don’t think honestly is answerable for many at all, is “What is my purpose in life?” I hate to bring in Taleb again. He’s been a big force in this conversation, but he has this perfect quote that deals with this. He says, “Life is more about execution than purpose.” At first, that seems kind of sterile or afraid of purpose or something, but in my experience, the only true purpose that I’ve ever experienced has been when I’m dedicated to taking action, when I’m focused on the actions that I’m taking. There was that book Start With Why. I think if you start with an abstract why, you’re going to end up with a really beautiful mission statement or a really beautiful poetic vision of your life, but it’s not something that’s going to hold up when you’re trying to take action. It’s not going to hold up when you’re struggling because you can argue against a beautiful written abstract sense of purpose. True purpose, to me, is something that is felt and probably only explained later.

Another bad question is “Do I love this person?” As soon as you try to answer that question, you’re not loving them. Love is a verb, in my view. Once you start to answer that question, you’re not taking the action of loving the person. You are separating from them and abstracting your relationship, which is a really easy way to talk yourself out of loving anybody. Then the fourth and probably the heaviest of them is “Why live? Why stay alive?” Albert Camus even said the only serious philosophical question is whether or not to commit suicide. If you want to take that challenge, you’re going to be really frustrated. People have been doing it for thousands of years and coming up with a lot of different answers. If you want to stick with logic, I don’t think anybody has come up with an airtight answer, but that doesn’t mean the question is relevant or hard to answer at all. It’s just hard to answer in the abstract.

When we pay attention to the actions we’re taking, when we’re taking earnest action, that question just can’t exist. That’s not a question that anybody asks that’s trying to do something. If you’re in the middle of playing a game of football or doing any kind of challenging task, you’re never going to ask yourself, “Why even live?” That only happens when you’re living in a purely abstract place. To me, action is always an obvious answer to the affirmative of that question. Like I said, all of those are just this breed of questions that ask too much from logic and don’t respect its limits.

Brett McKay: No, that question “What’s my purpose in life?” it made me think of Viktor Frankl. It’s been a while since I’ve read Viktor Frankl, but then … I forgot what I was listening to … made me want to revisit. I forgot that Frankl talked about this. He thought that asking about what your purpose in life was was a dumb question. He though it didn’t matter what we expected from life, but he said rather we should be focused on what life is expecting from us and then try to answer that question. That question is being asked to us daily, hourly, “What’s life?” His answer was you don’t respond with talk and meditation, but it’s right action, right conduct, in order to answer that question that life is asking you, what life is expecting from you at that moment, basically.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Yeah, and it’s never a romantic answer. It’s never going to sound world-changing. It’s never going to sound like something that you want on your bio. It’s going to be something really simple, really specific, probably, but it’s going to carry a lot of weight.

Brett McKay: That question can be like, “My purpose right now is to help my crying kid who’s being really annoying. I’m going to do this thing, get it done, but be patient and calm in the process.” That’s that thing. It’s very grounded in action.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Amen.

Brett McKay: You also say that action both makes things harder and easier. The way we’ve been talking about action makes it sound like, oh, it just opens these doors; you get these creative forces that come help you; you develop passion by taking action. How can action make things harder, as well?

Kyle Eschenroeder: There’s a trade-off here, and I think it’s one worth making. A lot of times, people say, “Well, here’s an answer. It’s obviously easier, and everything will work out if you take this stance.” I think what we’re talking about, there’s a whole host of benefits that make focusing on taking action worthwhile, but it also, I think, makes life significantly more difficult because you end up taking on more challenges, which means you end up taking on bigger challenges. Once you face the things that are immediately in front of you, your problems don’t usually get smaller. They tend to get larger in scope. You’re just growing enough to handle them.

You’re dealing with more pressing situations and putting more skin in the game. When you’re taking more action, when you’re focused on action, you generally have more immediately at risk. Your skin’s in the game, and you’re engaged in some version of the strenuous life that you wrote recently really beautifully about. Your article on the strenuous life, I think, in a lot of ways, talks about the harder aspects of a life of action. You’re under more strain. You’re under more pressure. You’re more committed. You’re more engaged. You’re more alive. You’re more virile. Life also becomes easier.

As you take on these bigger challenges, as you’re more engaged and pushing against more things, that means that you’re not ruminating. You’re not leaving as much space to drain yourself of energy while talking yourself in circles. You’re not justifying your decisions or your life to people who don’t matter. You’re acting, I think, more in line with nature because you get out of your head and into reality, where there’s ties between actions and consequences. You’re not breaking yourself to fit into a mold or checking off boxes that you think you’re supposed to. You’re becoming more self-reliant, I would say.

Things get harder, I would say, physically. Not strictly physically, but they get harder and there’s more strain probably. There’s more pressure, but easier in that more of that strain, more of that pressure, is coming from the outside, coming from challenging situations you’re putting yourself in and less self-harm and less respect for invisible obligations that society might be putting on us.

Brett McKay: Love it. Well, Kyle, there’s a lot more we could talk about. The Pocket Guide for Action is available for pre-order at The Art of Manliness Store. It’s pretty cool. Both Kyle and I have been working on this thing for months. We’ve self-published this thing, and that was some action that was hard, as Kyle can attest. We learned a lot in the process, but it turned out really great and we’re really excited about it. You can buy that on The Art of Manliness Store. Kyle, you’ve also set up an accompanying online course that people can take with The Pocket Guide to Action, right?

Kyle Eschenroeder: Yes. You can see some of the details at theactioncourse.com. The URL is in the book, I think on the book page. It takes the ideas from The Pocket Guide to Action and puts them in practices that you can apply immediately. There’s about 20 lessons that have 5 to 20 minute practices that will help you kickstart this habit of taking action.

Brett McKay: Awesome. Kyle Eschenroeder, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Kyle Eschenroeder: Thanks a lot, Brett.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Kyle Eschenroeder. He’s the author of The Pocket Guide to Action: 116 Meditations on the Art of Doing. It’s available at The Art of Manliness Store at store.artofmanliness.com. You can also find more information about Kyle’s work at kyleschen.com. That’s K-Y-L-E-S-C-H-E-N.com. Also, you can check out our show notes at aom.is/action, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out The Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy this show and have gotten something out of it, I’d appreciate it if you’d take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. That helps us out a lot. Another thing you can do is just share the podcast with a friend or family member, help spread the word, let more people know about what we’re doing here at The Art of Manliness. As always, thank you for continuing to support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.