A few weeks ago, I had futurist Kevin Kelly on the podcast to discuss the technological trends that are shaping our future. From driverless cars to artificial intelligence that will make new scientific discoveries, Kevin paints a fairly rosy picture of what’s to come.

My guest today sees a different side of the coin, and argues that the future envisioned by many in Silicon Valley is, well, kind of creepy.

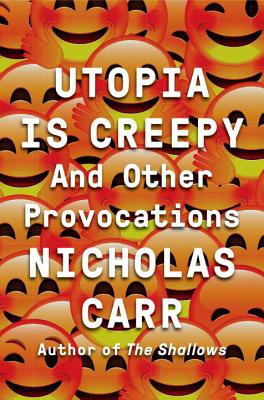

His name is Nicholas Carr, and he’s the author of several books that critique the wide-eyed utopianism of technologists. In his book The Shallows, he reported on the research that shows how Google is making us dumber; in The Glass Cage he explored the science on why outsourcing our work and chores to computers and robots might actually make us miserable and unsatisfied in life; and in his latest book, Utopia is Creepy, Carr pulls together all the essays he’s written over the years on how the rapid changes in technology we’ve seen in the past few decades might be robbing us of the very things that make us human.

Today on the show, Nicholas and I discuss why he thinks our utopian future is creepy, how the internet is making us dumber, and why doing mundane tasks that we otherwise would outsource to robots or computers is actually a source of satisfaction and human flourishing. We finish our discussion by outlining a middle path approach to technology — one that doesn’t reject it fully but simultaneously seeks to mitigate its potential downsides.

Show Highlights

- Why the ideology that Silicon Valley is promoting and selling is bad for human flourishing

- How the frictionless ideal of tech companies isn’t all it’s cracked up to be

- Why is the idea of utopia so creepy?

- Why don’t tech companies see that what they’re doing can be perceived as creepy?

- The illusion of freedom and autonomy on the internet

- What “digital sharecropping” is and why it exploits content creators

- The myth of participation and the pleasures of being an audience member

- Information gathering vs developing knowledge

- Why Nicholas doesn’t use social media

- The real danger that AI present humanity (and it’s not necessarily the singularity)

- Is virtual reality going to catch on? Does it present any problems for society?

- How can we opt out of the ideology that Silicon Valley is trying to sell?

- How to ask questions of our technology

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- My podcast with Kevin Kelly about the technological forces shaping our world

- My podcast with Matthew Crawford

- The uncanny valley

- How to Quit Mindlessly Surfing the Internet

- How to Break Your Smartphone Habit

- My podcast with Bill Deresiewicz on solitude and friendship

- Digital Sharecropping

- How to Read a Book

- 4 Questions That Will Cruch FOMO

- My podcast with Christina Crook about the joy of missing out

- The singularity

- Idleness Kills Manliness

- 5 Reasons Google Glass Failed

If you’re a bit leery of technology like myself, then you’ll definitely enjoy all of Nicholas’ books. Utopia Is Creepy gives you a big picture look at all of Nick’s ideas on the often overlooked downsides of our unquestioned adoption of digital technology. Pick up a copy on Amazon.

Connect With Nicholas Carr

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Playing With Science Podcast. A new sports and science show from StarTalk, the people behind Neil deGrasse Tyson’s hit science podcast StarTalk Radio. Subscribe in iTunes, Stitcher, or Google Play, or whatever you use to get your podcasts.

Bouqs. Valentine’s Day is right around the corner, so stop procrastinating. Secure a gift for your loved one now, with Bouqs. Go to Bouqs.com and use promo code “Manliness” at checkout for 20% off your order.

And thanks to Creative Audio Lab in Tulsa, OK for editing our podcast!

Recorded on ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. A few weeks ago, I had futurist Kevin Kelly on the podcast to discuss the technological trends that are shaping our future, from driverless cars to artificial intelligence that will make new scientific discoveries. Kevin paints a pretty rosy picture of what’s to come. My guest today sees a different side of the coin, and argues that the future envisioned by many in Silicon Valley is, well, kind of creepy. His name is Nicholas Carr, and he’s the author of several books that critique the wide-eyed utopianism of technologists. In his book The Shallows, he reported on the research that shows how Google is making us dumber. In The Glass Cage, he explored the science in why outsourcing our work and chores to computers and robots might actually make us miserable and unsatisfied in life. In his latest book, Utopia is Creepy, Carr pulls together all the essays he’s written over the years on how the rapid changes in technology we’ve seen in the past few decades might be robbing us of the very things that make us human.

Today on the show, Nicholas and I discuss why he thinks our utopian future is creepy, how the internet is making us dumber, and why doing mundane tasks that we otherwise would outsource to robots or computers is actually a source of satisfaction and human flourishing. We finish our discussion by outlining a middle path approach to technology, one that doesn’t reject it fully, but simultaneously seeks to mitigate its potential downsides. After the show is over, check out the show notes at AoM.is/UtopiaisCreepy where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Nicholas Carr, welcome to the show.

Nicholas Carr: Thanks very much.

Brett McKay: I’ve long been a fan of your work, The Shallows, The Glass Cage. Your new book is Utopia is Creepy, which is a collection of blog posts slash essays you’ve written over the years about technology’s influence on our cognition, how we think, our culture, our autonomy, the gamut. Let’s start with this broad question. One of the criticisms you make at Silicon Valley in particular is that they’re not just selling us gadgets and software. That’s what we think they’re selling us, but you argue they’re also selling an ideology. What is that ideology, and why do you think it’s bad for human flourishing?

Nicholas Carr: It’s an ideology that has deep roots in American culture and American history. There’s a strain of technological utopianism that runs through United States thinking, going back a couple of hundred years. It assumes a couple of things. One is that technological progress will bring us to … Will solve all our problems and bring us to some kind of paradise on earth. Second, and more insidious I think, it assumes that we should define progress as technological progress, rather than, and I think this is a better way to do it, rather than looking at technology as a tool that gets us to some broader … That moves us forward to some broader definition of progress. Cultural, social, economic, or whatever.

With Silicon Valley, I think it gives this long tradition of techno-utopianism a new twist, and kind of a new ideology that is all about venerating the virtual over the real. I think on the one hand, Silicon Valley is very materialistic. It wants to measure everything, and what can’t be measured is kind of not even worth keeping track of or giving any value to. At the same time, it hates the materiality of the world, and even the materiality of the human body. It believes that by virtualizing everything, by running the world with software and perhaps even creating a new virtual world out of software, we’ll solve the kind of messiness, the emotionalism and so forth that characterizes human beings, and also the messiness that characterizes the physical world.

I think Silicon Valley has this kind of misanthropic ideal that physicality is the problem that we need to solve, and if we can turn everything into algorithms and even turn ourselves into artificial intelligence, we’ll be better off.

Brett McKay: Right. They’re all about making things frictionless.

Nicholas Carr: Right. It turns out I would argue that friction is what gives interest and fulfillment and satisfaction to our lives. It’s coming up against the world, and figuring it out. Figuring how to act with agency and autonomy, gaining talents and skills. All these things that emerge from coming up against hard challenges and coming up against friction. I think this is what gives interest to our lives, and I think the tech industry sees all of this as something to get rid of. That the less friction there is, the more everything will run efficiently, and we won’t come up against challenges or hard work or things that might make us fail. It seems to me that that’s a recipe for removing satisfaction and fulfillment from our lives.

Brett McKay: Right. That’s why you think utopia is creepy, or at least how Silicon Valley envisions it?

Nicholas Carr: Well, I think beyond Silicon Valley, I would argue that all kind of visions of utopia tend to be creepy. There’s this famous concept of the uncanny valley in robots, and what that says is that the more humanoid a robot becomes, the creepier it becomes, because we’re very, very good at … We’re social beings, we humans. We’re very good at picking up signals from other living things, and it becomes immediately clear when there’s a robotic attempt to mimic a human being, that this is not a human being. We get creeped out, and that’s one of the big problems that roboticists have as they cry to create humanoid robots, is that these always seem creepy to us, and that’s the uncanny valley, that it’s very hard for roboticists to cross.

I think something very similar happens in portrayals of utopias, because almost by definition, there’s no tension in a utopia. No friction. Everybody behaves very well. Everybody’s on their best behavior all the time, and when you see that, all of a sudden you realize that, you know, people begin in utopias … People act very robotically. They’re very efficient. They have no messy emotions. They don’t get angry. I think that characterizes utopias in general, which is one of the reasons that in science fiction, we’re much more drawn to dystopian portrayals of the future as this horrible mess, whereas attempts in fiction or in movies or whatever to create a vision of utopia always turns out to be more repellent than the dystopia is, because we don’t see any human qualities there.

I think the ideal that Silicon Valley has, the utopian ideal where everything is very efficient and runs on software, is very much this kind of creepy ideal, that in order to achieve it you have to drain human beings of what makes them human.

Brett McKay: Why do you think they still have that drive? I mean, why don’t they see the creepiness of it? I look at them like, “Man, that’s weird.” Why don’t they see it?

Nicholas Carr: Well, you know, I think some of it comes from their personalities. That I don’t think … This is a generalization, but I think it’s to some extent true. A lot of the leaders in Silicon Valley have spent most of their lives interacting with the world through computer screens, and that suits their personality. They’re not necessarily open to ambiguity or to messy emotions, or the kind of social conflicts that come whenever you engage with people face to face and with the world. I think they come from … You know, I think their ideals reflect a personality that is very comfortable with computers, and very comfortable with software and programming, but when things aren’t programmed, and things happen unexpectedly and perhaps inefficiently and ambiguously, they draw away from those things.

I think in some sense, what the world that Silicon Valley wants to create, and to me it’s a very robotic world, is the world that these people actually want to live in.

Brett McKay: That’s interesting. Which is strange, because you know, the internet, one of the promises of the internet would be like it would be this sort of … It would be a sort of utopia where you have different types of viewpoints, different types of ideals, all together that anyone can access, but the way it’s worked out is we have these people at the top who are actually structuring the internet in a way that suits their personality and the way they like things, and we have to go along with it.

Nicholas Carr: Right. One of the things I try to … When I put together Utopia is Creepy, this collection, one of the things I did is read through my blog going back a dozen years, and I realized that a lot of the dreams about the internet, and ones that a lot of us held when we first started going online, not only haven’t panned out, but in many cases the opposite has happened. We thought that by going online, we’d bypass centralized hubs of power, whether it’s political power or media power or economic power, and we’d have this great democratization where everyone would have their own voice, and we’d listen to lots of different viewpoints. What’s happened is we’ve really seen an incredible centralization of power, power over information, so you get a handful of companies like Google, and Facebook, and Amazon, and so forth that control now huge amounts of the time people spend online, and huge amounts of the information that they get.

More and more of our experience is being filtered by these companies, and needless to say, they’re motivated not only by their ideology, but by their desire to make money. These are profit-making companies, of course. I think a lot of the feelings about democratization of information, about people broadening their viewpoints, has not panned out, and I think what we’re learning is that when we’re bombarded by information the way we are these days, we actually become less open-minded and more polarized, and more extreme in our views. I think we saw that in the recent election, and I think we see it in political discourse, that our hopes about how society and ourselves would adapt to having this constant bombardment of information just haven’t panned out, and now we have to struggle with consequences that we didn’t foresee.

Brett McKay: Right. I think one of the insidious things about the internet, or at least the way it’s structured, is that it gives us the illusion that we have freedom, right? Like we can spout our opinion on Facebook or Twitter, and we think we’re participating in democracy, and that we’re expanding our viewpoints, but you argue … I mean, I think you just made the point that it actually is an illusion. Like, it actually reduces our autonomy and it reduces our agency.

Nicholas Carr: I think that’s right. Some of that is simply because we become more reflexive when we have to process so much information, so many notifications and alerts and messages so quickly that we have to deal with it in a superficial fashion. We may think we’re being participative if we click a “like” button or Retweet something, but really this is a very superficial way of being involved and participating, and it’s on the terms determined by the technology companies, by the social media platforms. It’s in their interest to get us kind of superficially taking in as much information as possible, because that’s how they collect behavioral information. That’s how they get opportunities to show us ads.

You know, I would argue that on the one hand, there’s the great benefit of the internet, which is that it does give us access to information and to people that used to be hard to access or impossible to access. On the other hand, what it’s stolen from us is kind of the contemplative mind, the calm mind that takes this information, takes our experiences and our conversations, and quietly makes sense of them. I think that ultimately, you know, you need that space in which to think by yourself, and without interruption, without distraction, in order to develop a rich point of view, and hence express yourself and communicate yourself in a rich way, rather than this reflexive way that we’ve adapted to online, which does give us this illusion that we’re constantly participating, constantly part of the conversation, but really kind of ends up narrowing our perspective, makes us more polarized, makes us quicker to reject information that doesn’t fit with our existing worldview.

I do think there’s this kind of illusion of thinking and illusion of participation that often isn’t the reality of what’s going on.

Brett McKay: Right. Along that lines of participation, one of the benefits that technologists tout about the internet is that it democratizes the ability to create content, right? We’re no longer just consumers. We’re also creators, but what people forget is that, like, you’re creating that for the company. You’re kind of working for the company for free, right? When you create Amazon reviews, or create YouTube videos, or create content on Facebook or Twitter.

Nicholas Carr: That’s right, and this is something I coined a term, “digital sharecropping.” Kind of an ugly term, but I think it describes this. That whether it’s Google search engine, or whether it’s Amazon reviews, or whether it’s the entirety of Facebook or Twitter, essentially the content that these companies use to make money off of is the content we create. Similar to a sharecropping system where a plantation owner would give a poor farmer a little plot of land and some tools and then would take most of the economic value of any crops that were grown, we’re given by these social media platforms these little plots of land to express ourselves and to develop our profiles, and to share and so forth, but all of that creativity that goes into that is monetized by the company, so we become these people who create the content without getting any compensation for it, any monetary compensation for it, that allows companies like Facebook and Google to become enormously rich.

That’s not to dismiss some of the opportunities that the web does really give us to express ourselves. I mean, as I say, I’ve written a blog for a long time, and I enjoy that, and I feel like I’ve been able to clarify my own thoughts as well as speak to an audience that I might not have, but I do think we need to recognize the kind of economic dynamic that underlies a lot of what we do online, and how in a very real sense, even though we don’t notice it, we are being exploited and manipulated, and kind of outside of our own consciousness sometimes, we’re kind of employed without pay to create these huge, very, very powerful and very rich companies, as well as very rich owners of them.

Brett McKay: Right. I thought another point you made was funny, is that the idea that, “Oh, if you democratize that, we’ll suddenly have all this great stuff. This great content.” But, like, most of the content that’s amateur created is crap. I mean, I know it’s mean to say, but like Instagram comedians are the worst. I don’t understand why people think that’s funny, but apparently it’s a thing.

Nicholas Carr: Yeah, and it kind of … Sometimes it shows that the audience, you know, when they get free stuff, they’ll look for the most superficial kind of buzz, and that will be enough because nobody’s encouraged to spend time kind of developing taste or thinking too carefully about things. You know, this kind of dream that everybody is going to be a great writer or a great filmmaker or a great musician, unfortunately it’s just not true. I think a lot of people understand that. I certainly understand that I’m not going to be a great songwriter and so forth.

Again, this is another illusion that the web sometimes gives us, that it’s always better … What the web tells us is this kind of myth of participation, that if you’re just passively reading something or watching a movie or a TV show, or listening to a podcast, that there’s something wrong with that. I would argue that that’s exactly the opposite. That a lot of the greatest satisfactions come from being a member of an audience of good stuff, and that we shouldn’t feel that if we’re not … We shouldn’t mistake kind of a rich experience of other people’s creative work as a passive experience. It’s actually very active, as anybody who’s read a great novel or watched a great play or anything knows. The web and a lot of the companies on the web kind of encourage us to think that we have to be active and participative and creative all the time. Well, that’s very important, but let’s not lose sight of the great pleasures of being an audience of really good stuff.

Brett McKay: In The Shallows, you take a look at how the web has changed our brains. You talked about, you began the book talking about how you’ve noticed your brain change over the years. Like you can’t focus as much, it’s hard to sit through and read a book for a long period of time. One of the arguments you make in that book is that every information technology … We’re talking the alphabet, the book itself, and the internet, carries with it intellectual ethic. What’s the ethic of the internet?

Nicholas Carr: Yeah. What I mean by that is that all of these media technologies encourage us to think in a particular way, and also not to think in other ways that they don’t support, and that this is the ethic. I think what the digital technologies in general, and the internet specifically, it values information gathering as an end in itself. What it says is the more information that we have access to, the faster that we are able to process it, the more intensively it bombards us, the better. That more information is always better. What’s lost in that, I think, is what everyone used to understand, which is that information gathering, very, very important, but it’s only the first stage in developing knowledge, and certainly the first, an early stage in developing wisdom, if we ever get to that. But knowledge isn’t about just gathering information. It’s about making sense of information. Going out, having experiences, learning stuff, reading the news, taking in information, but then backing away from the flow of information in order to weave what you’ve learned together into personal knowledge.

This is what’s lost, I think, in the ethic, the intellectual ethic of the internet. This sense that there are times when you have to back away from the act of information gathering if you’re going to think deeply, and if you’re going to develop a rich point of view, if you’re going to develop a rich store of knowledge. You can’t do it when you’re actively distracted and interrupted by incoming information. I think the internet is very very good as a tool for information gathering, but what it encourages us to do is to think that we should always be in the process of gathering information, and I think that’s the danger that the web presents.

Brett McKay: How do you counter that?

Nicholas Carr: Not very well, sometimes. I mean, this is also something I talk about in The Shallows. I think as human beings, we have this primitive instinct to want to know everything that’s going on around us, and I think this goes back to, you know, caveman and cave woman days when you wanted to scan the environment all the time, because that’s how you survived. We bring this deep information gathering compulsion into this new digital world where there’s no end to information, and as a result, and I think all of us see this in ourselves, we become very compulsive about wanting to know everything that’s going on on Facebook, or in news feeds, or through notifications and so forth. We kind of constantly pull our our phone or our computer and look at it, even if it’s completely trivial information. I think there’s this deep instinct that the net and technology companies tap in to that can become kind of counterproductive, that keeps us gathering information and glued to the screen.

To me, the only way I’ve found to combat this is to resist some technology. For instance, I don’t have … I’m not active on Facebook or on most social media, and it’s not because I don’t see the benefits of social media. It’s because I know that these systems are designed to tap into this instinct I have to want to be distracted and interrupted all the time, and in order to avoid that I just have to say, “No.” I’m going to lose the benefits of Facebook. I mean, one thing you realize when you’re not on Facebook is, for instance, nobody wishes you Happy Birthday anymore because you’re not on Facebook, but nevertheless it does seem to me that in order … If you value kind of the contemplative mind, the introspective mind, the ability to follow your own train of thought without being interrupted sometimes, then you have to shut down some of these services and make the social sacrifices that are inherent in shutting down services that increasingly are central to people’s social lives.

At this point, it’s a very difficult challenge to kind of bring more balance into your behavior, into your mind, into your intellect. But to me, at least my hope is that I can raise awareness that there are sacrifices that are being made here, and we should be a little more diligent, I hope, in figuring out which of these technologies are really good for us, are making us more intelligent and happier and more fulfilled, and which are simply tapping into this compulsive behavior that we often evidence.

Brett McKay: One assumption that technologists have is that we’ll be able to find technology to fix problems, even problems caused by technology. I mean, do you think someone in Silicon Valley will come up with something to fix the problem of the distractibility of the internet?

Nicholas Carr: I think there are technologists who are trying to do that. I mean, I think we’ve seen an increasing awareness among the public and among people in Silicon Valley, or in other technology companies outside of Silicon Valley, that this is a problem. That we have created a system that has huge benefits and huge potential, but increasingly it is keeping people distracted and thinking superficially, and often polarized and unable to give credence to people’s points of view that don’t fit their own. I think you see kind of attempts to create apps or other software programs that reduce the intensity of the flow of information, that kind of vary the flow of information, turn off some feeds at times when people might get more out of thinking without distraction and being alone with their thoughts than looking into a screen, kind of creating a more unitasking environment where there aren’t lots of windows and lots of tabs and lots of notifications going.

The problem is that these are a hard sell, because we’ve adapted ourselves very very quickly to this kind of constant bombardment of information, and this sense that we’re missing out if we’re not on top of everything that’s happening all the time, so I do think, and I think we see this historically, that often technology rushes ahead and creates problems that were unforeseen, and you can solve some of those problems with new technology. We certainly see it in driving, for instance, with the creation of seatbelts and all sorts of technologies that kind of make cars safer and so forth. But it can be … There’s always this kind of tension between the momentum a technology gains as it moves ahead and as we adapt ourselves to it, and the need to sometimes back up a little bit to redesign things to better fit with what makes us interesting, well-rounded people.

I think there are ways to deal with some of these problems technologically through better design of systems, better design of software. The question is, will we, as the public, accept those? Those technological advances? Or are we stuck in this pattern of behavior that has been inspired by the technology and the companies that are dominant in the technology?

Brett McKay: Right. The other issue is, there’s really no money in that, right?

Nicholas Carr: Yeah. As long as … I mean, one of the big issues is that we have set up the web and social media and so forth as an advertising-based system. If we were paying for these things … You know, there was a time in the era of the personal computer, where if you wanted to do something with your PC or your Mac or whatever, you’d go out and you’d buy a piece of software, and you’d install it, and then you’d use it for whatever you wanted to accomplish, and that was actually a pretty good model. We’ve abandoned that model for a model of, you know, “Give it to me for free but distract me with ads and collect information about me.” Getting away from that would mean actually having to pay for stuff, and we’ve so adapted ourselves to the idea that everything is free, that, boy, getting people to pay for something that they could get for free is a really, really hard sell.

Brett McKay: Hard sell. In The Glass Cage, you take a look at artificial intelligence. This is the stuff that creeps me out the most, is AI. I had Kevin Kelly on the podcast last week, talked to him, and he’s pretty … He’s gung-ho about this, and it’s great, but AI gives you pause. Why is that?

Nicholas Carr: For a number of reasons. And again, I don’t want to come off as just reactively against progress in computing and progress in AI, because I think there are ways that we can apply artificial intelligence that would be very good, and that would help us out, and would help us avoid some of the flaws in our own thinking and our own perspectives. First of all, the definition of AI has gotten really fuzzy. It’s hard to know … These days technology companies call pretty much everything AI, but where I see the problem with artificial intelligence as it begins to substitute for human intelligence, in analyzing situations, making judgements about situations, making decisions about it, is that it begins to steal from us our autonomy, our agency, and also steals from us opportunities to build rich talents of our own.

I think we can see this in a simple way with navigational technologies. You know, Google Maps, or GPS systems in your car. That on the one hand they make it very, very easy and kind of mindless to get from one place to another, but as a result we don’t develop our own navigational skills, and also we don’t pay attention to our surroundings and so don’t develop a sense of place. It turns out that those types of things, the ability to make sense of space and of place and to be attuned to your surroundings, is really pretty important to us. I mean, we are physical creatures in a physical world, and we have evolved to be part of that world. What we don’t … In our drive to make everything more convenient and easier, often we sacrifice the things we take for granted, which are all about learning to navigate the world and have agency in the world and have autonomy in the world. We kind of take those for granted, and so we’re very quick to lose them in order to gain a little bit more efficiency or a little bit more convenience.

It does strike me that, you know, beyond the kind of doomsday scenarios or the utopian scenarios of the singularity, and you know, computers overtaking human intelligence, at a practical level the danger is that as computers become more able to sense the environment, to analyze things, to make decisions, that we’ll simply become dependent on them, and we’ll lose our own skills and our own talents in those regards. You know, our own ability to make sense of the world and to overcome difficult challenges. We’ll simply turn on the machine and let the machine do it. Unfortunately, that’s a scenario that gives us great convenience and great ease, but also I think, and this goes back to something we talked about earlier, also steals from us the opportunity to be fulfilled as human creatures in a physical world.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Like with self-driving cars, like I still don’t get it, because I enjoy driving. I don’t know why I’d want to give that up. Everyone says, “Oh, well it’s safer. You can be more productive.” It’s like, “I actually enjoy driving.”

Nicholas Carr: That’s true of … I completely agree with you, and the last thing, even though I realize that there are ways, and this has been a long story with automobiles. There are ways for technology to make driving safer, and I think that’s very, very important. The fact is that, you know, most people, and it’s like 70% to 80% of people, actually enjoy driving. It’s not like they’re blind to the dangers and to traffic jams and to road rage and all the horrible things that come with driving, but there’s something very pleasant about driving, about being in … It’s actually one of the rare times that we as individuals are actually in control of a very sophisticated machine, and there’s pleasure that comes with that, and there’s this sense of autonomy, and a sense of agency. In some ways, this is kind of a microcosm of the Silicon Valley view.

Silicon Valley dismisses … I think Silicon Valley is totally unaware of the pleasure that people get from things like driving, and so that leads them to simply see driving as a problem that needs to be solved, because there are accidents, because there are inefficiencies, because there are traffic jams. All of that is what they focus on, and so their desire is to relieve us of what to them is this horrible chore of driving a car, and so they don’t realize that for a lot of people, that driving is really a great pleasure, and owning a car, and all of that. To me, that kind of puts in a nutshell the tension between the Silicon Valley ideal and how people actually live, and how they get some satisfaction out of life.

Brett McKay: Right. Again, it’s this idea that they’re giving us freedom, but in the process, we have to give up freedom to get that freedom.

Nicholas Carr: Right. They’re giving us freedom … They’re freeing us from that which makes us feel free, I think you could say.

Brett McKay: Then we find out we actually enjoyed those burdens, when it’s finally taken away. We feel existentially empty. We’re like, “Oh, I don’t do anything.”

Nicholas Carr: Right, and I do think that there is some evidence, and I think this both comes from psychological studies, but also from our own experience, that when we’re freed of labor and freed of effort, we actually become more anxious and more nervous and more unhappy, and it turns out that it’s the chores that software frees us from that are often the things that bring us satisfaction, that in our life, that the experience of facing a difficult challenge and developing the talents required to overcome that challenge, that’s very deeply satisfying, and yet if you look at the goal of software programmers these days, it’s to find any place where human beings come up against hard challenges and have to spend lots of time overcoming them, and kind of automating that process. That’s why in many cases we think our lives are going to be better when we hand over something, some chore, some task or some job to a machine, but actually we just become more nervous and anxious and unhappy.

Brett McKay: Right. What’s your take on virtual reality? I mean, it’s crazy. Like, I remember back in the 90s, like, I’d go to the science museum and they had the VR thing. You could go through the human digestive system. That was the thing. Then I thought, “This is the future. This is amazing.” Then, like, it died. It didn’t go anywhere. Now we’re seeing this resurgence. Does virtual reality give you pause? Do you think it’s going to catch on this time?

Nicholas Carr: I mean, there’s the kind of physical question of, “How long can people be in a virtual environment without getting nauseous or dizzy or whatever?” Let’s assume that that will be solved, that we’ll figure out how to create systems of virtual reality that are actually pleasant to be in. Well, I think it will have successful applications. I mean, I can see it in gaming. I can see it in certain marketing aspects, you know? If you’re looking to buy a house or something, or rent an apartment, you’ll be able to put on your virtual reality goggles and walk through the space. You can certainly see applications in pornography, which will probably be one of the first to come along.

What I don’t think will happen … I think there’s this belief Mark Zuckerberg, I think, from Facebook has stated it, that virtual reality goggles will become kind of the next interface for computing, so we’ll spend lots of time with our goggles on, or in some kind of virtual reality, in order to socialize. That’s what social media will become, and what personal computing will become. I don’t think that that’s going to happen, because … And I think you see signs of this from, like, the failure of Google Glass, that there’s something about … I think there’s some deep instinct within us, and within probably all animals, that resists having something else control our senses, something else control … Something get in the way of our field of vision. I think we can do it for brief periods. We can do it when we’re playing a game, or when we want to accomplish a particular task that can be accomplished through virtualization of space or whatever, but I don’t think we’re going to see people walking around with virtual reality goggles or even with simpler device, projection devices. I’m very dubious about kind of smartphones being replaced, for instance, by virtual reality systems.

Brett McKay: Right, because it looks goofy. It looks creepy.

Nicholas Carr: It looks goofy, and it looks creepy, and it also … You feel vulnerable. You feel weird, when you’re seeing something that some … When you’re cut off from the actual real world and embedded in a world that somebody else is manipulating. I mean, it’s disorienting, and it’s also I think, we’re repulsed by it after a while.

Brett McKay: Nicholas, there are people who are listening to this and they agree with you. Like, “Yeah, utopia is creepy.” Like, “I’ll take some of this utopia that they’re offering, because there’s some benefits to it, but there’s parts of it I just know I don’t want to go …” Is it possible to opt out? I guess it is possible. You don’t do social media.

Nicholas Carr: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Any other ways to opt out?

Nicholas Carr: I mean, I do a little. For instance, I’m on Instagram, but I have a private account with a handful of close friends and family members, and it’s really good. I mean, if you restrict … If you place certain restrictions on social media, I think it can be very, very valuable and very fun. I’m not arguing for total opting out, as if that were even possible. I mean, I think one thing we know about the internet and computers and smartphones is that it’s actually very, very hard to live these days without those kind of tools, because society as a whole, our social systems, our work systems, our educational systems, have rebuilt themselves around the assumption that everybody’s pretty much always connected or at least has the ability to connect very frequently.

I don’t think … Some people will opt out totally, just as some people opted out of television totally and so forth, but I think those will be people on the margins. For most people, I think it’s really, the challenge is really more about developing a sensibility of resistance, rather than a sensibility of rejection. Often, techies will quote Star Trek, say, “Resistance is futile.” You know, “The Borg of the internet is going to take us all over, so just give in to it.” I think that’s absolutely the wrong approach. I think it’s valuable to resist these kind of powerful technologies, and this is a powerful technology. It’s a media technology that wants to become the environment in which we exist, and I think it’s important to resist, and by “resist” I mean, instead of being attracted to whatever’s new, to the latest novelty, to the latest gadget, to the latest app, always pause and say, “How am I going to use this? How do other people use this? Is this going to make my life better? Am I going to be happier? Am I going to feel more fulfilled and more satisfied if I adopt this technology, or am I just going to be more distracted, more dependent on technology companies? Less able to follow my own train of thought? Less well-rounded?”

I think if we just start asking these questions, and everybody’s going to have different answers to these, but if we start asking these questions, I think we can become more rational and more thoughtful in what technologies we adopt, and what technologies we reject, and ultimately I think that’s the only way to kind of balance the benefits and the good aspects of the net and all related technologies with the bad effects. By now I think we all know that there are bad effects, that this isn’t just a story of, you know, everything getting better. It’s a story about costs and benefits, and we have to become better at balancing those, and that really does mean becoming more resistant and more skeptical about the technology and the promise that’s being made about the technology.

Brett McKay: Well, Nicholas, this has been a great conversation. Where can people learn more about your book and your work?

Nicholas Carr: Well, you can go online. Yeah, my personal site is NicholasCarr.com, where you can find out information about my books and links to my articles and essays that I’ve written. My blog, which I still write, though not as intensively as I used to, is called Rough Type, and you can find that at RoughType.com.

Brett McKay: Awesome. Nicholas Carr, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Nicholas Carr: The pleasure was all mine. Thank you.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Nicholas Carr. He’s the author of several books including The Shallows, The Glass Cage, and Utopia is Creepy. All of them are available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find more information about Nicholas’ work at NicholasCarr.com. That’s “Carr” with two Rs, C-A-R-R.

Also check out our show notes at AoM.is/UtopiaisCreepy, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at ArtofManliness.com. This show was recorded on Clearcast.io. If you’re a podcaster who does remote interviews, it’s a product that I’ve created to help avoid the skips and static noises that come with using interviews on Skype. Check it out at Clearcast.io. As always, we appreciate your continued support, and until next time, this is Brett McKay, telling you to stay manly.