In the modern day, it’s conceivable that a man might never find occasion, outside a wedding, to propose a toast. And even when called upon to give one in the role of best man, he is very likely, despite being given plenty of lead time to practice, to bumble through a largely forgettable tribute.

Yet throughout history, and amongst cultures around the world, the picture couldn’t have been more different. From the banquets of ancient Greece to the business luncheons of the early 20th century, a man could hardly attend any meal or gathering without witnessing, and initiating, countless toasts.

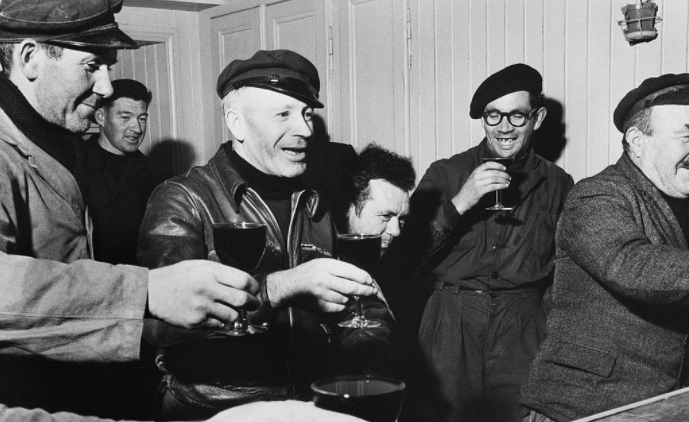

For thousands of years, toasting was in fact a central and exclusive part of men’s classical honor culture. It was a ritual that, if often taken to excess, was animated by the ethos of competition, tested the masculine quality of improvisation, required the risk inherent to performance, and built bonds of brotherly camaraderie.

In more modern times, giving a good toast became a mark of a real gentleman — someone who was adept at oratory, agile with improvising rhetoric, and knew just what to say to enhance any holiday or social occasion.

Toasting not only has a long, storied history, but remains a useful ritual, providing a singular way to express sincere and affectionate sentiments, show off a bit of your personality, bring people together, and make special events even more special.

So here at AoM we say it’s high time to bring back the toast in all its glory. Today we’ll dive more into why, beginning with a brief look at the tradition’s fascinating (and often manly) history.

A Brief History of Toasting

The act of toasting may very well date to prehistoric times, and we know with certainty that it existed amongst many early peoples, including the Hebrews, Egyptians, Persians, Saxons, and Huns.

Toasting’s origins in the West most directly trace to ancient Greece. It likely began with the Homeric age ritual of showing obeisance to the gods; the supplicant would take a vessel of wine in the right hand, pour out a portion of the drink in sacrifice, lift both hands above the head in prayer, and then drink of the cup himself. This ritual of raising a toast to Hermes, the Graces, and Zeus, naturally evolved to raising a drink to one’s fellow man.

Ancient toasters might choose a classic, set toast that had been passed down for ages or decide to improvise one on the spot. The Greeks proposed short toasts to fallen comrades, to war, to peace, to leaders, to beautiful women, and most common of all, to their companions’ health — as Odysseus does to Achilles in the Odyssey. This practice continued in ancient Rome, and was even perpetuated via legislation; the Senate issued a decree that all citizens were to toast to the health of Emperor Augustus during every meal. But it was largely an act designed to honor one’s personal comrades or to assess the intentions and “gameness†of one’s guests.

Indeed, amongst both the Greeks and Romans, toasting could not only serve as a declaration of well wishes (and an excuse for copious drinking!), but also a provocation — a challenge. Being able to hold one’s liquor was considered a form of toughness and discipline, and a night of toasting surely tested a man’s capaciousness. Just as the Greeks who pledged their drinks to the gods expected blessings in return for their sacrifice, toasts made to one’s fellow mortals were expected to be reciprocated. One toast would beget another, and back and forth the tributes went. With each, the vessel would have to be entirely drained of its intoxicating contents; as we’ll see, merely sipping one’s drink after a toast is a modern refinement. Thus, offering a toast was sometimes a way of throwing down the gauntlet — an invitation to competition and a kind of duel; could the others match you cup for cup? Unsurprisingly, a night of toasting frequently found participants passed out in a stupor by its end.

The popularity of toasting continued through the Middle Ages and beyond, becoming so ubiquitous by the 1600s that, according to one Englishman, “To drink at a table without drinking to the health of some one special, would be considered drinking on the sly, and as an act of incivility.â€

Formerly, and during this time, toasting was largely considered an activity for men only; after a meal, the sexes would separate, and the men would begin their endless rounds of toasts. Getting thoroughly sotted was considered unbecoming for a lady, as was overhearing the salty language with which men typically surrounded the ritual. Toasts were also used to solidify the bonds of male honor groups, not only through the competitive element of drinking, but by way of the pledges of loyalty that often accompanied them. For example, bands of early warriors took to not only wishing for their comrades’ good health, but promising to protect that health themselves. When various European peoples clashed during the Middle Ages, raiders would often storm their foes’ dining halls, cutting their enemies’ throats as they feasted. For this reason, the Anglo-Saxons began swearing protection to a brother while he engaged in the vulnerable act of drinking.

The tradition of toasting remained widespread for several centuries more — again, particularly among men and when ladies weren’t present. In fact, the first temperance societies (established in the 16th century) were formed by groups of women who wanted to abolish toasting since it was the cause of so much excessive imbibing. Yet, although anti-toasting crusades gathered steam and some laws and decrees were issued to abolish the practice, toasting’s popularity continued unabashed; for example, during a dinner in America in 1770 that brought together 45 male friends, no less than 45 toasts were given (presumably one for each man in attendance). In fact, it was during the 18th century that the role of toastmaster was created to function as a sober referee who ensured everyone who wanted to toast got the chance.

Even among those who recognized toasting’s excesses, there were some who saw its potential for good. For example, in his toast anthology published in 1791, The Royal Toast Master: Containing Many Thousands of the Best Toasts Old and New, to Give Brilliancy to Mirth and Make the Joys of the Glass Supremely Agreeable, J. Roach argued:

“A Toast or Sentiment very frequently excites good humor, and revives languid conversation; often does it, when properly applied, cool the heat of resentment, and blunt the edge of animosity. A well-applied Toast is acknowledged, universally, to sooth the flame of acrimony, when season and reason oft used their efforts to no purpose.â€

Roach called for toasts to be made to virtuous sentiments, like “Confusion to the minions of vice!†and “May reason be the pilot when passion blows the gale!â€

Toasts did indeed take a turn during this time to the more high-minded — though they could still be as cheeky as ever. During the Revolutionary War, Americans’ toasts often took the form of vexes on the British: “To the enemies of our country! May they have cobweb breeches, a porcupine saddle, a hard-trotting horse, and an eternal journey!†After the war, Fourth of July celebrations were always accompanied by toasts to the signers of the Declaration of Independence, as well as thirteen toasts in honor of each of the thirteen states.

With the overall revival of the art of oratory in the 18th century, toasts could become masterful pieces of rhetoric (if sometimes morphing into long-winded speeches) and studded with sharp political commentary and wit. When Benjamin Franklin was acting as the American emissary to France and attending a government dinner there, he listened as the British ambassador introduced a toast to “George III, who, like the sun in its meridian, spreads a luster throughout and enlightens the world.†Then a French diplomat offered his own toast to “The illustrious Louis XVI, who, like the moon, sheds his mild and benevolent rays on and influences the globe.†At last it was Franklin’s turn to pay tribute to his boss. Raising his glass, he proposed a toast to “George Washington, commander of the American armies, who, like Joshua of old, commanded the sun and the moon to stand still, and both obeyed.â€

During the Victorian age, an ascendant honor culture that focused on character virtues and good manners curbed the excesses of toasting and further refined the ritual. It became more common in mixed company, and simply sipping the drink after a toast replaced the tradition of draining one’s vessel dry. A kind of competitive element to toasting remained, but came to center on the quality of one’s toast, rather than on how much alcohol one could imbibe.

This ushered in a “golden age†in the rhetoric of toasting which lasted from about 1875 to 1920. During this time, men worked hard to compose toasts that deftly combined the right mix of wisdom, wit, and solemnity, according to whatever the occasion called for. Newspapers printed columns of toasts, book anthologies offered readers thousands of ideas for them, and comic writers made their reputations on a knack for penning humorous tributes. As Paul Dickson notes in Toasts, almost nothing and nobody could escape this particular kind of commemoration:

“Toasts were written for every imaginable institution, situation, and type of person— cities, colleges, states, holidays, baseball teams, fools, failures, short people, and fat people. A British collection contained a toast, several pages in length, written for ‘The Opening of an Electric Generating Station.’ Occupational toasts were very popular, and some clubs and fraternal organizations opened their dinners with a toast to each of the professions represented at the table.â€

Of course, in the United States, Prohibition put a severe damper on the tradition of toasting. For over a decade, booze was hard to come by, and though toasting was naturally still engaged in, its popularity declined when it could only be done in dark, secret gatherings (or with a glass of root beer in public).

While there was a short resurgence of toasting after Prohibition was repealed in 1933, it remained in a general decline for the rest of the 20th century. Toasting’s expressive, sincere nature clashed with the age’s more closed-off, circumspect, cynical tone, and it seemed like just another stuffy tradition that took up too much time and detracted from having an “efficient†meal.

Nowadays, the tradition of toasting has largely disappeared (at least in the States; it continues on more strongly in some other countries) and become something we primarily only see at weddings . Which, frankly, is a real shame.

Why We Should Bring Back Toasting

“[Toasting’s] use is well-known to all ranks, as a stimulative to hilarity, and an incentive to innocent mirth, to loyal truth, to pure morality and to mutual affection.†–J. Roach, The Royal Toastmaster, 1791

While we certainly aren’t advocating a return to the overflowing competitive drinking and toasting of centuries past, nor of trotting out long-winded toasts for every event, toasting really should be engaged in a bit more often than it is. Here are a bunch of reasons why:

Requires risk and courage. While toasting doesn’t have much of the competitive element these days (if you give a toast, you’ll likely be the only one who does, and thus won’t be compared to anyone else), it still does require a dose of courage to attempt. It’s a mini performance, one that requires facing the chance of achieving great success, or stumbling over what you say. Your toast may bomb or soar — that’s the wonderful, heart-enlivening risk of it!

Requires practicing the art of oratory. A toast is nothing more than a very short speech. As such, you’ve got to be adept in how to arrange and convey rhetoric for maximum effect. We get too little practice in public speaking as a whole these days; toasting gives you a chance to exercise your chops.

Involves the manly art of improvisation. While you may prepare a toast beforehand, part of it should always be improvisational — you tweak the toast according to the mood and needs of the particular event and crowd at hand. And you may find yourself in a spot where you didn’t realize you’d be making a toast, but are asked to do so, or just unexpectedly stumble into what seems like a fitting moment to volunteer one. Toasting thus requires you to be able to think fast on your feet.

Injects a bit of dramatic anticipation into an event. When you give a toast, not only will you be feeling some nerves, but your audience will experience a bit of compelling tension as well. They’ll be interested in hearing what you’ll say and how you’ll say it — whether you’ll flounder or succeed. There’s a little anticipation and suspense — a bit of drama in the best sense — that adds to the interest of the occasion.

Prompts you to share sincere feelings you might otherwise not. We often think of nice things we’d like to say to others, but have a hard time finding an appropriate moment to express them — one in which it won’t sound awkward or out of place. The established ritual of toasting facilitates the sharing of these hard-to-express feelings. As Dickson puts it, “toasts are so useful. They are a medium through which deep feelings of love, hope, high spirits, and admiration can be quickly, conveniently, and sincerely expressed.†Since people are already expecting something a little more sentimental with a toast, it gives you an excuse to be so.

Plus, not only does the structure of toasting allow you to get away with expressing things you might otherwise have a hard time articulating, it also ensures you actually follow through with getting them out; once you rise to your feet and raise your glass, there’s no turning back!

Enhances the mood of an occasion. At a going-away party, a toast that wistfully recalls wonderful memories of the soon-to-be-leaving can stir up poignant feelings of nostalgia. At a birthday party, a witty toast can put the attendees in stitches. At a holiday feast, a sentimental toast can evoke a warm sense of gratitude amongst the company present. Toasting can provoke, heighten, and even change the mood of an event; it adds a special something to a special occasion.

Dickson perfectly describes toasts as a “verbal souvenir†of a time together well spent.

Inspires feelings of togetherness and camaraderie. If you combine the toaster’s performative risk and the audience’s sympathy for it, the shared feelings of anticipation and mood, and the common witness to publicly shared sentiments, you’ve got a recipe for building closer bonds. There’s something about all that, and especially about a communal, embodied ritual, that really brings people together. In mixed company, such togetherness evokes feelings of warm affection; in groups of all men, it takes on that particular tinge of masculine camaraderie.

All in all, giving a toast is an excellent challenge for the individual who initiates one, and makes for a more memorable occasion for all those who witness and receive it. Toasting is an excellent platform for eliciting laughter, dispensing well wishes, and offering sincere veneration for worthy people and events. Doesn’t the world need much more of all of these things? Indeed it does. So let’s bring toasting back.

Next time, we’ll talk about how.

___________________________________

Sources:

Toasts by Paul Dickson.

The Rituals of Dinner by Margaret Visser