When Kate was in her mid-20s, she noticed that her beloved nana was starting to slow down and get more frail. Having heard that studies had shown that taking just a short walk a day could help the elderly stay healthy and avoid disability, and wanting Nana to stick around as long as possible, Kate often encouraged her to take regular strolls — advice which, to Kate’s frustration, she rarely took. “It’s so easy to take a short walk,” Kate would muse to me. “I wonder why she doesn’t do it?â€

Fast forward a decade or so, and to another conversation between Kate and I. “Boy,†she said, “it sure seems to be getting harder to want to move rather than sit now that I’m in my 30s. I wonder if it just keeps getting harder to get up and go with every decade of your life, so that by the time you’re in your 80s, the inertia is super strong. That’s probably why Nana didn’t do her walks.â€

I thought of this exchange recently when I heard about a recent study which showed that daily moderate to vigorous physical activity significantly cut the risk of mortality — even if accumulated in chunks of ten minutes or less. Basically, that cliché advice to park far away from the store entrance or to take the stairs instead of an elevator turns out to be dead-on, and potentially life-saving.

Movement staves off death because it’s good for the ticker, good for the waistline, and good for the mind.

People often use age as an excuse for gradual (and sometimes not-so-gradual) weight gain over the years. But while metabolism does decrease about 10% each decade, that slowdown is largely not a function of age, but a result of the loss of muscle mass. People get fatter not because they get older, but because as they get older, they stop moving. They get more and more inert. They slow down, their lifestyle becomes more sedentary, their muscles deteriorate, their metabolism declines, and fat accumulates.

At the same time, physical activity wards off depression and anxiety, so that a lack of movement sickens the mind as it weakens the body.

A sedentary life thus easily turns into a cycle of greater and greater passivity. Once you stop moving, you gain weight/get frailer, and feel more depressed, which makes you less motivated to move, and when you do move, it feels harder, more uncomfortable, and less pleasurable. This only makes you less likely to move, which makes you gain more weight, become more decrepit, and get more depressed, which drives you deeper into the chair and the couch.

On the flip side, movement (especially that which involves some resistance) preserves your mood, your muscle mass, and thus your metabolism. The more you move, the easier it is to stay moving — a positive cycle is created: your body stays leaner and your joints stay limber; your mind stays more positive and motivated; you want to move more, and it feels good when you do.

The rolling stone gathers no moss; the moving man gathers less fat.

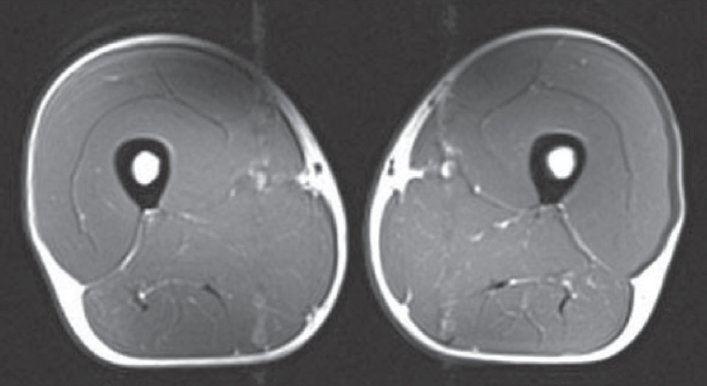

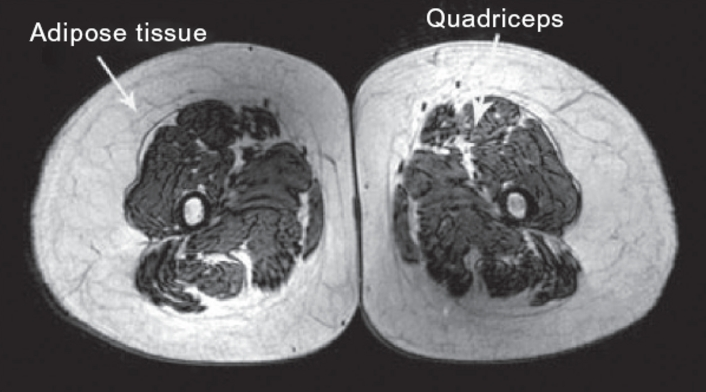

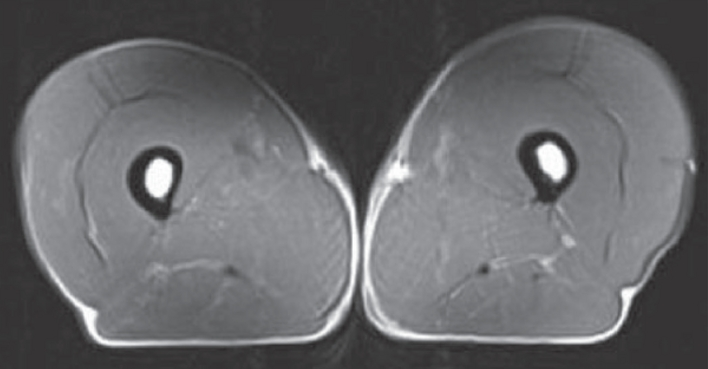

Look at this MRI scan of the quadriceps of a 40-year-old triathlete, and then compare the stark visual difference in fat/muscle composition that can be seen in scans of two 70-something men — one who is sedentary and the other who is a competitive triathlete:

40-Year-Old Triathlete

74-Year-Old Sedentary Man

70-Year-Old Triathlete

As the authors of the study for which these scans were made conclude: “It is commonly believed that with aging comes an inevitable decline from vitality to frailty . . . This study . . . show[s] that we are capable of preserving both muscle mass and strength with lifelong physical activity.”

Be the Shark

Bodies at rest, stay at rest; bodies in motion, stay in motion.

The easiest way to keep moving, is to stay moving.

Picture your body, mind, and spirit like one of those exercise bikes they have at science museums, where you have to keep pedaling to keep a light bulb lit.

Or better yet, picture yourself as a shark. Some sharks have to swim almost constantly in order to breathe. Same thing with you. You got to keep moving to “breathe†— to maintain the vitality of both your body and mind. If you don’t keep moving, you’ll die. Not right away, but slowly. And quicker than you otherwise would.

While you wouldn’t believe it in your 20s, it does get harder to want to move as you get older. Who knows why. Less motivating dopamine in the brain? Less novelty and more boredom with routine? The cumulative effects of earth’s gravity? Whatever it is, know you’re going to have to intentionally maintain the will to move.

Remember that daily physical activity doesn’t have to be a full workout (though dedicated exercise is excellent, of course).

Do actually take the stairs. Carry a suitcase rather than wheeling one around. Take short breaks from work to walk or perform the Daily Dozen Exercises.

Keep swimming. Keep breathing, Keep moving. Keep living.