One criticism that is occasionally leveled at this site is that we are “overly nostalgic.” The critic will say that we are promoting the false idea that everything was better in the past.

Now you won’t find anywhere on the entire site where we argue that everything was better in the “good old days.” Anyone who’s not a fan of the plague, slavery, or World Wars understands the fallacy of such an argument. What we do argue is that the last few generations, eager to break away from what was wrong with the past, ended up throwing out the baby with the bathwater. The mission of the Art of Manliness then is to let that which was wrong with the past remain in the past, while recovering the positive things that could benefit today’s men.

Still, there will be those that say even this sort of nostalgia is misplaced. They argue that every generation looks back on the past as a golden age, and that every era was really just as good and just as bad as every other, and if anything, we live in the best period in all history. Nostalgia seems to be taking a beating lately, so I’d like to mount a defense for it. I will argue that some ages were better than others, and that not only is nostalgia not misplaced, but that a healthy dose of it, even if you already think the world is a grand place, is the key to making things even better.

What Is Nostalgia?

When putting forth a thesis, it’s best to first define your terms. While I’m not a fan of citing Wikipedia as a source, it can be a good place to look for succinct definitions. Here’s the entry for nostalgia:

“The term nostalgia describes a longing for the past, often in idealized form. The word is a learned formation of a Greek compound, consisting of νόστος, nóstos, “returning home,” a Homeric word, and ἄλγος, álgos, “pain” or “ache.”

So let’s say that nostalgia is an aching for the past, a longing to return “home,” to a place or time where we feel things were better. So now let’s proceed.

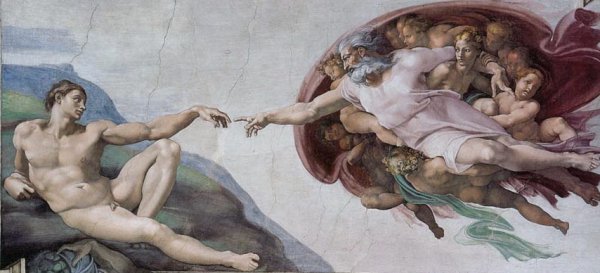

Nostalgia as the Catalyst for Progress: The Example of the Renaissance

Some would argue that looking back and idealizing the past is unproductive, but history has shown that the opposite is true. This can be clearly seen in the origins of the Renaissance period. We have to get through some history to understand how this is so, so bear with me; I promise I have a point.

The Crises of the 14th Century

At the dawn of the 15th century, Europe was in a foul mood. The 1300s had been a tumultuous and ghastly period.

The English invaded France in 1337, setting off the Hundred Years War. But it was only one of the long, protracted wars of the 14th century, each leaving corpses strewn across bloody battlefields.

In addition to the sword, people were being mowed down by disease. The Black Death wiped out a mind-boggling 1/3 to 1/2 of the population. The plague was not only disastrous to people’s health but also decimated the economy, leading to a depression that would last nearly a century (and you thought the current recession was bad!).

The final blow to the people of the 14th century was a schism that developed in the Catholic Church. Between 1378 and 1417 there were 2, and for a time 3 different popes, each claiming to be the legitimate head of the Church. The popes excommunicated all the people under the opposing pope’s control, thus cutting them off from salvation.

There is much to be said about each of these three crises, but suffice it to say that at the end of the 14th century, the people of Europe (if they weren’t dead) were bitterly disillusioned and greatly pessimistic about the future. People’s faith in government, in the church, and in their fellow man was badly shaken. Apocalyptic thinking reigned and many believed they were living in the last days.

At this point Europeans could have given in to the hopelessness, resigning themselves to the idea that the world was going to hell in a hand-basket.

But instead, they decided to proactively and courageously meet the challenges of this crisis of confidence; they sought a revival, a rebirth and renewal of society. They idealistically believed that they could build a new world.

There have been moments like this at other times in history, most recently the 1960’s where idealistic hippies believed they could form a new world where peace and love ruled the day. That project was largely unsuccessful and in many ways led to the cultural excess and stagnation we are currently experiencing. But the result of the European project was one of the greatest cultural flourishings in world history: the Renaissance period. The difference? While the movement of the 1960’s was built on the idea of starting with a clean slate, the Renaissance was founded on….yup, you guessed it, nostalgia.

Nostalgia and the Birth of the Renaissance

The intellectuals of the 15th century came to see the Middle Ages as universally a time of disaster, decay, and corruption. This was not actually true; despite what you heard in your history class, the Dark Ages were not a complete wash. Yet they knew that many aspects of their society had declined and regressed and that their culture had stagnated.

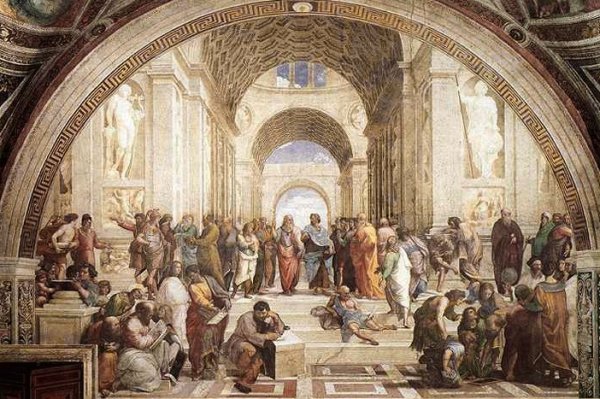

These intellectuals began to look back on Ancient Greece and Rome as the golden age of world history, a great period of culture, joy, and learning. Those were the “good old days!” they said. With this new historical vision, they began to work out a plan to revive their society, using the golden age of antiquity as their template and inspiration.

Italian scholars began to rediscover and pore over texts from ancient Greek and Roman authors. As they studied the ancient sophists, they digested the Greek idea that truth was relative when it came to rhetoric, that if someone is convinced by an argument , then it is true for that person. As they thought through the idea that there could be different truths for different people, they began to apply it to the subject of history and discarded the idea that all history could fit under one overarching plot and could be measured by the same rubric. They concluded instead that every era was unique and different, each with its own characteristics and circumstances.

This led them to understand that bringing back the classical period wholesale would be impossible, that you couldn’t simply replicate an entire age. While they still saw antiquity as a golden age, these new humanists realized that the ancient era would not match up exactly with theirs and instead decided to resurrect antiquity in a modified version, taking what was best about the Greek and Roman societies and adapting them to their age and circumstances.

The humanists’ vision of this remade world was to be something both ancient and modern. They looked back to the past while moving forward into the future. It was both historical and progressive, and this brilliant combination led to a profound cultural flowering in art, architecture, music, and writing, the cultural outpouring that many still consider second to none in world history. The “Dark Ages” were left behind and a new world was born.

Applying the Lessons of the Renaissance to Our Modern Age

So anyone see where I’m going with this? By romanticizing a period as a “golden age” and yet being flexible enough to understand that not everything from the past should be brought back, the Renaissance was born.

These days we’re in need of a Menaissance. And we can bring one about with a healthy dose of nostalgia-idealizing a golden age while modifying it to fit the modern age.

Like the late 14th century, we’ve woken up from a bad period, and many are feeling pretty depressed about the state of things. Now I know some people think the world is in total decline and some think we’re getting better and better-but bright minds can disagree on this issue, and I’m not particularly interested in that debate.

What I don’t think can be argued against is that cultures do rise and fall-you either believe that cultures rise and fall while the world as a whole gets better, or as the world as a whole gets worse. And no matter whether you think we’re currently going uphill or downhill, I believe that the ability to look back in history and take lessons from the cultural peaks of the past is essential to the continued progress and health of our society. While our problems might be small compared to the plague, our age does struggle with serious issues and our confidence is pretty dang shaky these days.

We’ve been in this kind of place many times in history, and we can either sink into cynicism and despair, or we can courageously rise to the challenges of our age by looking to the past and resurrecting what was best about it.

Moving Forward by Looking Back to Another Golden Age

While it’s true that every generation romanticizes the past, it’s not true that every age is equally romanticized. Who gets very nostalgic for the 70s and 80s (the pang you feel in your heart when you hear Journey notwithstanding)? When’s the last time you heard someone wax poetic for the 1910s or 1890s? And surely no one in the future will look back on the “oughts” with longing in their heart.

And there’s a reason for this! While some things, maybe most things, get better with the progression of time, some things, even if only a few things, get worse and become utterly lost. And the period we get nostalgic for typically represents that which we feel is missing in our current culture. It’s not as if we wish to return wholesale to that period, but that we wish to bring back those characteristics which were most salient about that time and which seem absent in ours. The intellectuals of the 15th century longed for the intellectualism, the philosophical reasoning, the political participation, the elevation of the human form and the rhetoric of classical antiquity, the things which had largely gone missing during the Middle Ages.

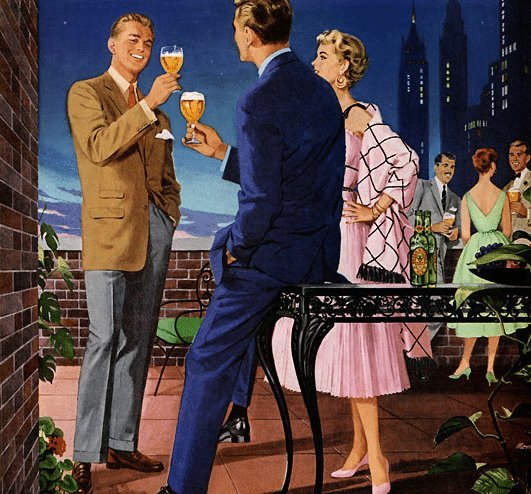

These days we “ache” for our last “golden age,” the 1940s and 50s. Postwar prosperity created a tide that lifted nearly every boat, a man could make a middle-class living with a blue collar job, corporations looked out for their employees (back then the ratio of CEO pay to the average worker was 24:1, it is now 275:1!), and people still believed in the importance of dressing well, having manners, and respecting others. It was a classy time. And it was a stylish time. On TV, Father Knew Best and on the silver screen Cary Grant was suave manliness incarnate. Look at any old photo from the time, and the men look back with confidence and purpose.

It was not necessarily a more moral time-there was still crime, babies born out of wedlock, and adultery galore. But there was an enormous difference in the celebration of ideals, in the idea that being good and doing good was, if not totally attainable, still a worthy pursuit. This is in contrast to our age, the Age of Irony and Cynicism, the motto of which may be, “Why bother?” The corrosive effect that cynicism has had on our culture and on men is so important that we’ll be devoting a whole post to it in the future, but for now all I can say is thank you Conan, for saying cynicism is your least favorite quality. It’s mine too (even though I struggle with it myself).

Now again, the idea is not that 40s and 50’s were perfect; they weren’t. No the idea is to take inspiration from the period in order to create a revival of modern society. The idea is to admit that it doesn’t make sense to be relativistic about everything, to be willing to admit that some things, even if only a few things, really were better in the past.

Three years ago, Tulsa unearthed a 1957 Belvedere that had been buried as a time capsule 5 decades before. The unearthing of the car was news around the world and people were fairly giddy with excitement to see this beautiful automobile reemerge from the ground (unfortunately, water had gotten into the vault and rusted it out). Tulsa buried another car that year, this one to be unearthed in another five decades. What car? A Dodge Prowler. A Dodge Prowler! Who will give a crap in 2057, will have an aching, a longing to see the Prowler lifted from the ground? Very few. Why? Because the cars of the 1950s were beauties and we haven’t produced anything since then that inspires the love and devotion that those long lines and beautiful styling did.

All of which is to say again, that some things in the past really were better. And if we want to move forward, what we should do is embrace and resurrect those things. Not necessarily to bring back cars with fins, of course. But things with quality. Things that were made to last and that you wanted to take care of.

This sturdy, lasting quality was not simply present in products. It was an a by-product of a culture that meant something, a culture with rules. I think Matt Higgins explains this best in his article, “The Comeback of Construction“:

“Mad Men” never forgets to show us that this culture was socially and behaviorally homogenized, racist, sexist, and severely limited opportunity for many. But it was something. A shared something hanging over everything, inflecting life by its mere presence, inescapably shaping you by your relationship to it. It was constructed and agreed upon and provided a stable narrative and worldview based on shared mythologies, dreams, and values.

And in the midst of our aggressively egalitarian politically correct efforts to erase society as our grandparents knew it, people are finding that they miss something about the good old days. The sophistication of a man in a suit and top hat, the elegance of a lady in an evening gown, the chivalry of a traditional date. The cultural codes that shaped our world for so long have been replaced by a one-size fits all code of jeans and whatever-you-want. A deconstructed, post-modern, supply-your-own meaning culture.

And it works. To an extent. Because it offers people ample freedom to do their own thing. But people are finding that they miss some of the benefits of construction. We are living in an age of overwhelming and disorienting freedom. Freedom is a great thing, but like music without measures there comes a point when the absence of structure leads to the dissolution of meaning. Music becomes noise.

And as a society we’re getting tired of the noise. Young people shaping culture today are making important efforts to bring back rhythm and meter from the void. Costumes, customs, ways of standing and moving and speaking, a return of construction is in progress all around us.”

Conclusion

An unhealthy nostalgia thinks everything was better in the past, and impedes cultural progress with constant hand wringing about the modern age. Healthy nostalgia is grateful for the modern advances that have made life better, but misses some things from the past and works to bring them back.

For the last few decades, every generation has wanted to reinvent the wheel, wiping the slate clean to make society new from scratch. But just as dangerous as hyper-nostalgia is hyper-presentism. This postmodern world sees only the current moment with no sense of history and of what came before. We’ve thrown out all the old rules but failed to make any new ones.

Scrapping the project every decade in favor of building on the latest societal fads and winds of change only results in a ramshackle shell of a culture, one which shivers in the wind until the next generation knocks it down and gets to work on its own shaky edifice.

Ideally, what should happen is that each generation should take what was best from the generation before it and add it as a brick in the foundation of the culture, discarding the dross and ever stacking together the lessons we’ve learned, the things that have really worked best. This way the culture becomes stronger and stronger over time.

So I say that I unapologetically get nostalgic for the postwar period and that I believe it can be a source of inspiration for us today. And I humbly submit that when you’re seeking a revival, a renewal, a real renaissance, looking back is the best way to move forward.

Listen to our podcast on nostalgia: