The Gila National Forest covers about 3.3 million acres in southwest New Mexico. During the dry summer season, wildfires pose a serious threat to the area. To spot wildfires in this vast landscape as soon as they start, the U.S. Forest Service relies on fire towers spread throughout the area that are each manned by a lone individual. My guest today wrote a memoir about the unique experience this job offers. His name is Philip Connors, he’s a writer and one of the country’s few remaining fire watchers. Today on the show we discuss what the life of a fire watcher is like and what it’s taught him about nature, solitude, and time. Along the way, Phillip describes the virtues of listening to baseball games by radio and the value of slowing down in an increasingly rushed world.

Show Highlights

- The history of fire towers in the West

- The decline of these towers (and why they aren’t used as much anymore)

- Why some environs still require fire watchers, and what drew Philip to the job

- What happens when a fire is spotted?

- Philip’s day-to-day routine as a watcher

- Is the solitude unnerving?

- On balancing solitude with community/sociability

- The changes over the years in how Philip perceives nature

- How fires themselves have changed over the years

- Does Philip get bored? How does he pass the time?

- Why Philip writes in longhand when he’s at the fire tower

- The virtues of listening to baseball on the radio

- The biggest fire Philip has seen

- Takeaways on life and nature that Philip has gleaned from his decades as a watcher

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

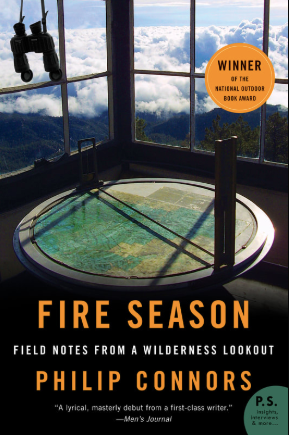

- Fire Season: Field Notes from a Wilderness Lookout (Philip’s book about being a fire watcher)

- The Big Burn by Timothy Egan

- Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It

- Jack Kerouac’s 63 days on Desolation Peak

- Gila National Forest

- Osborne Fire Finder

- The Adventure of Silence

- Lessons on Solitude From an Antarctic Explorer

- How to Score a Baseball Game With Pencil and Paper

- Megafire by Michael Kodas

Connect With Philip

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Podcast Sponsors

ZipRecruiter. Find the best job candidates by posting your job on over 100+ of the top job recruitment sites with just a click at ZipRecruiter. Visit ZipRecruiter.com/manliness to learn more.

Proper Cloth. Stop wearing shirts that don’t fit. Start looking your best with a custom fitted shirt. Go to propercloth.com/manliness, and enter gift code “MANLINESS†to save $20 on your first shirt.

Art of Manliness Store. From t-shirts, to mugs, to posters, and other unique items, the Art of Manliness store has something for everyone. Use code “aompodcast” for 10% off your first purchase.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. The Gila National Forest covers about 3.3 million acres in Southwest New Mexico. During the dry summer season, wildfires pose a serious threat to that area. To spot wildfires in this vast landscape as soon as they start, the US Forest Service relies on fire towers spread throughout the area that are each manned by a lone individual.

My guest today wrote a memoir about the unique experience this job offers. His name is Phillip Connors. He’s a writer and one of the country’s few remaining fire watchers.

Today on the show, we discuss what the life of a fire watcher is like and what it’s taught them about nature, solitude, and time. Along the way, Phil describes the virtues of listening to baseball games by radio and the value of slowing down in an increasingly rushed world. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/firewatch. Philip joins me now via clearcast.io. Here we go. Philip Connors, welcome to the show.

Philip Connors: Thanks. It’s great to be with you.

Brett McKay: So, you’re a writer, but you found yourself in an interesting seasonal career as well a couple of years ago as a fire watcher on a fire tower in the Gila National Wilderness area in New Mexico. Before we get to your experience, I don’t think a lot of people know about fire towers in America and like what they do. So, can you give us a brief history of fire towers in the American West?

Philip Connors: Yeah. They really took off as a phenomenon early in the 20th century with the advent of the US Forest Service, and there were some massive wildfires in the Northern Rockies around 1910 that kind of encoded in the DNA of the early forest service, a desire to stamp out forest fires as quickly as possible. So one of the ways of doing that, of course is early detection.

So, fire towers were built on many a mountaintop in the American West. Some had already been in place in the East even before then, but by 1940 or so, there were probably about 8,000 fire towers across the country, and the idea was you place a human being up on a mountaintop with a 360 degree view, and that person, by staying vigilant, will give you quick detection of a forest fire and allow firefighters to jump on it right away and stamp it out.

Brett McKay: So, they pretty much lived up there for months at a time by themselves.

Philip Connors: Right. The early fire lookouts would typically go to a mountain well away from a road and just stay there for the duration of fire season, from when the snow melted in the spring and until weather changed in the late summer or fall that fire danger would finally be lessened.

You know, there’s some great writing that’s come out of the job, Norman Maclean, in his book of stories, A River Runs Through It, wrote about being a fire lookout in 1919 in Montana, and he basically went up and lived in a tent, climbed a tree several times a day for a look around. And that was the job. And he would use a crank telephone to call in fires to the ranger station below.

Brett McKay: And Jack Kerouac also did that, right?

Philip Connors: He did. He spent one season in the North Cascades, Washington State, and he made much of that experience in multiple books of his. He’s probably the most famous literary fire lookout of all, even though he only spent 63 days on Desolation Peak and seemed to find it a disagreeable experience, too much solitude.

Brett McKay: Right. We’ll talk about the solitude here in a bit and your experience with it.

Another interesting … I remember reading through … I collect old men’s magazines from the 50’s and 60’s. I think it was True magazine. They had a feature about one thing that some newlywed couples would do back in the 50’s was for their honeymoon or shortly after they got married, was they would go and just do a firewatch for a couple months, and that was their honeymoon. I thought that was an interesting article.

Philip Connors: Yeah. You know, I met someone who did that on the mountain where I work back in the early 50’s. I just happened to run into her in a restaurant in a very small town in Southern New Mexico, and she started talking to me, and I told her where I was working. I was just on days off from the fire tower, and she said, “Oh my husband and I spent our honeymoon there back in 1953.” When she was 17 or something, and he was 20 years old. So yeah. It was a thing.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it’ be funny. “Hey honey, we’re going to go be alone for three months or four months on a mountain.”

Philip Connors: If you want to test the strength in their relationship, I guess that would be one way to do it.

Brett McKay: That’s the way to do it.

So, there were 8,000 of these towers at one point, but they’ve been declining. How many are there in existence today, and why are there so few?

Philip Connors: So, the numbers that I’ve been hearing in the last few years are that somewhere between 400 and 500 are still staffed, mostly in the American West. There are other countries, of course, that used them too, Australia and places in South America, but in the United States it’s a few hundred, and there’s a variety of reasons why the number has declined. Partly, it’s just development into formerly forested areas.

Once upon a time, it was … Only a lookout could see a fire in certain places in say California, but with home construction and development into those areas, it’s just as likely that someone standing on their back deck will see the fire as quickly as a lookout would, and in other places, they’ve just gone to different detection methods like overflights with airplanes, and there’s just a continual push to use more technology in place of actual human beings. I mean, we see that across our entire society, but it’s also true for lookouts that people dream of using infrared cameras linked with pattern recognition software or satellites, maybe unmanned aerial vehicles, drones. So all of those things have pushed lookouts, not to the brink of extinction, but we are definitely a dwindling, threatened species.

Brett McKay: Well, let’s talk about how you got connected with this. When did you start working a fire tower in New Mexico? How did that happen?

Philip Connors: So, my first year was 2002, 16 years ago, and I just got lucky. I got a note from a friend of mine, an old friend from the University of Montana, and she wrote to me and said that she had got a gig as a summer lookout down in the Gila in New Mexico and that I should come visit. At the time, I was working as a copy editor in New York City at the Wall Street Journal. So, she sort of teased me and said, “Get your flabby white keester out of that cubicle and escape the canyons of Lower Manhattan for a view from a mountain in New Mexico.”

So naturally, I couldn’t resist that invitation. I flew to Albuquerque and drove south from there a couple of hours and met up with my friend, and we hiked in to this fire tower many miles from the nearest road. She was on days off when we met up, and I spent 72 hours there and just absolutely fell in love with the view, the landscape, the lifestyle, the essence of the job.

And she had been there, by then, for months and was kind of itching for more action than one typically sees just living on a mountaintop. She wanted to go fight a fire. So, she talked her boss into letting her do that and allowing me to slot in as her replacement for what remained of that season, and the rest is history. I’ve gone back every summer since 2002.

Brett McKay: How long … So you start in the summer, how long are you there? How long does a fire season last?

Philip Connors: So, our fire season starts pretty early because we’re so far south. We typically kickoff with fires in April, and I’ll be on the mountain typically until sometime in August. Every year we get a monsoon rain weather pattern that puts an end to fire danger here, usually starting sometime in July and extending into August. So, most seasons I’ll work from early April to at least mid August.

Brett McKay: And so, you’re in the Gila National Wilderness Area, correct?

Philip Connors: Yeah. It’s the Gila National Forest, which is 3.3 million acres, and inside of that is a protected roadless wilderness area of half a million acres.

Brett McKay: Gotcha. And why are there still towers there? Is it just because it’s so large or is it more susceptible to fires?

Philip Connors: Actually both. It’s a very large landscape, like I said, 3.3 million acres. The Gila National Forest is as large as some small eastern states, and it is very susceptible to lightning-caused wildfires. The nature of the landscape, it’s very dry. It’s very arid forest, and it gets hit by lightning than any other landscape in America aside from the Gulf Coast Region. So, combine those two things, very arid, flammable fuels and lots of lightning, and so every season we see typically hundreds of wildfire starts in the Gila, and because it’s not very settled, there aren’t many towns nearby or within the forest, it still does require eyes in the sky to detect wildfires there.

Brett McKay: So, you’re not the only tower there. There’s other towers in the area.

Philip Connors: That’s correct. There are 10 of us actually still staffed in the Gila, which probably is more than any other forest in the lower 48.

Brett McKay: So whenever you see a wildfire … So, I imagined you see the smoke first, what goes on? How do you all triangulate where the fire’s at? How does that work?

Philip Connors: So we’re all equipped with two essential tools. One is a two-way VHF radio so we can communicate with other lookouts and with dispatchers and with firefighters on the ground. And we have this tool that really hasn’t changed in 100 years called the Osborne Fire Finder, which is essentially a sighting device. It’s almost like a gun sight, and what you do with it as you zero in on the precise location of the smoke, and you’re right, it is typically smoke you see first, not flames. And when you do that, it’ll give you a compass reading expressed in degrees from zero to 360. That is what we call the azimuth, which is basically a straight line between your location and the smoke.

And then what we can do with that is talk to other lookouts and say, my azimuth is say 90 degrees from my location. That other lookout, if he or she can see the smoke will also come up with an azimuth reading, and then we turn to these maps of the forest, which are typically on a dropdown board on hinges within our fire tower, and we just cross our lines on those maps using compass rosettes that are affixed to the map, and it’s a simple case of triangulation, and if we have at least two lines from two different locations to the smoke, then we can pinpoint it with great accuracy.

Brett McKay: So you said you see a couple hundred of these lightning-started wildfires, do you get like an adrenaline rush still? Like anytime you see smoke, like you get excited and you feel your heart go fast or have you gotten used to it where it’s just like part of the job?

Philip Connors: Yeah, you’d think after 16 seasons and many dozens of fires called in from my location, it would kind of get to be old hat, but it is the case that, for me anyway, I still do get that adrenaline rush. Partly it’s just knowing that I’m the only person in the world seeing this natural phenomenon, and I’m about to sound the alarm and give the fire a name. All of those play into the adrenaline rush, and sometimes you can go weeks, maybe even a couple months, staying vigilant and nothing happens, and then all of a sudden one day it’s there. So yeah, it never does fail to be thrilling.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that was an other thing I didn’t know, that fires get names, and the person who sees it first gets to name it, sort of like a hurricane gets a name.

Philip Connors: Right. Yeah. We typically try to give it a name that’s based on a local landmark, so you know, a river or canyon or the name of a peak or some other prominent local landmark. So, usually when you hear fires in the news it’s because someone spotted it, and a lot of places where there aren’t lookouts, it’ll be the firefighters or the dispatch center that gives it a name, but still here on the Gila, it’s the lookouts that name the fires.

Brett McKay: So, let’s talk about … I think the thing that I found most fascinating about this was your experience with solitude in nature because this is something that I think a lot of people today don’t experience. So, before we get to the specific instances of that, let’s talk about your accommodations to give people an idea of what your day to day was like.

So, there’s a fire tower, like where did you sleep? Is there like a cabin on top of the tower that you slept in?

Philip Connors: At my mountain, there’s a cabin down below the tower, unconnected with the tower. A lot of lookouts have living towers that are roomier. They’re say 12 by 12 or 14 by 14 feet, often with a catwalk around the exterior. My tower is one of those bare bones utilitarian spaces that’s seven by seven feet and not really a livable space. It’s just big enough to hold the Osborne Fire Finder and allow one person to walk around the outside of it.

So, there’s a cabin that’s been there for many, many decades where I live, and it’s just right below the tower.

Brett McKay: Okay. And so when you went there, like how far away were you from like humanity? I mean, was it hundreds of miles away? I mean, how alone were you?

Philip Connors: Not quite that extreme. I’m five miles from the nearest road, and that road will take you to a town with adult beverages and a lunch spot in about a 40 minute drive. So, it’s relatively isolated just because of the distance from automobiles, but if I hike real fast down the hill to my truck and speed off away, I can be having … I could leave my tower and be drinking a beer in like two and a half hours.

Brett McKay: Gotcha. So how long did you go without seeing or talking to anyone when you’re up on a season?

Philip Connors: It varies quite a bit. I’m there for 10-day stretches at a time, and then I get four days off. So during those 10 days I live there, stay there, sleep there. During the four days off I hike out and go home. But during those 10 days, I might see nobody for 10 days. It’s pretty rare that that happens, but it has happened, and other times I’ll see day hikers when the weather’s nice in the summer. I might see day hikers three or four days in a row, maybe a couple one day and three or four people the next day, and then I’ll go four or five days without seeing anybody. So it’s pretty variable. It often depends on just how good the weather is and how much people decide they want to get out and take a walk. But it is still possible for me to go 10 days without seeing anybody, which is always rather delightful for me.

Brett McKay: Yeah that was something I was going to ask you. Was that unnerving? But, it sounds like you actually enjoyed that solitude.

Philip Connors: Yeah. On the contrary, for years and years, every time I heard hikers coming up to hill having a conversation with each other, or maybe just saw them appear through the trees at the edge of the meadow, my heart would sink because I’d think, “Ah, Jeez, I got to exercise my vocal cords and give my little public relations speech about wildfire and what this place is all about.” But over the years, I found that if you’re willing to hike five miles uphill for the sheer pleasure of it, you’re typically a quality human being. So, I’ve come to treasure my interactions with strangers who show up there unannounced and just accept that that’s part of the deal. You know, I’m lucky I get to live for months each year on a piece of public land that’s owned by all of us. And so I don’t need to get all possessive about it. It’s owned by every other American too. So if they want to come and enjoy it, take a hike, see the view from a mountain, they should absolutely do that, and I’ll try to be as welcoming as I can while they’re there.

Brett McKay: I’m curious, do you notice. Do you like go through a transition from there’s a you that is you before you fire season where you’re interacting with people, probably more regularly than you do when you’re on a fire season. Like is there a difference between that you and then as you go further, further, deeper into the season where you’re more and more alone, like do you change at all? Do you notice a change in your brain? Do you know what I’m trying to ask here?

Philip Connors: Yeah. You know, I do. My wife would probably tell you that come late February, early March of every year, I start to get a little anxious, maybe even a little unpleasant to be around, and it’s because I’m looking forward to this incredible experience that I keep having summer after summer and keep loving more and more the more I do it.

It’s interesting because I have that 10-day stretch of work there and then four days off. It’s not like I unplug so radically from the world for a really long stretch of time. I come to treasure that balance between solitude and sociability. So, on my days off every other weekend, it’s kinda fun to get together with friends and catch up and sit down and gossip or have a couple beers, and then I get to escape again and go hang out by myself for 10 days.

At the end of the season, I do always find it’s really hard to let go. The season is always too short, no matter how long it extends. I’d probably prefer to be there about 10 months a year instead of five, but it’s just part of the deal. It’s a seasonal job. Living there in the winter would probably be really brutal anyway because it’d be really cold up above 10,000 feet. So I try to just remember all things in moderation and all things in balance. The solitude and the social mobility, the high country bliss and the neon plastic valleys. It’s all part of my life and I try to remain pretty balanced about it.

Brett McKay: How has your connection to nature changed since working as a fire watcher? Because you’re an interesting position because you’re observing nature from a very macro level. It’s not like you’re like looking at an individual leaf like a botanist, but like you’re looking at an entire landscape. So, I imagine that’s changed the way you perceive nature in some way.

Philip Connors: Yeah, it has. It’s interesting because I get to spend more than 100 days there every year. I can spend a whole afternoon like down on my hands and knees if it’s a cloudy day and fire danger is really low, like geeking out on short horned lizards and salamanders poking out of their holes in the metal below my tower. So I can spend time focused on the micro world and the micro life that I share the mountain with.

And at the same time, I’m mostly looking at a piece of country that’s really big. From from my tower, I can see … Oh, if you went to the horizon and drew it out on a map and lined it, you’d probably encompass an area of close to 20,000 square miles. I mean it’s a phenomenal view. You can see forever, and one of the interesting things about the experience of being there as long as I have is I’ve seen changes, changes that are happening on a landscape scale. The fires keep getting bigger and hotter. A lot of the old growth forest that has been there since who knows, it’s probably been there in some form or another, burning and regenerating for 10,000 years, a lot of it’s going away now, and it doesn’t seem like it’s going to come back because of climate change.

So yeah, I toggle back and forth between that real closeup, micro attention to the world around me up there and the big picture view, which, to me, is rather scary watching it change on a landscape scale relatively quickly.

Brett McKay: Besides the sight, is there something about the sound? Like is it just like supremely quiet up there or is it actually pretty loud with the wind?

Philip Connors: It depends on the season and the day. The springtime tends to be very windy there, and the noise of that can be deafening and actually challenging for one’s mental health to live amid that howl day after day. I’ve measured wind gusts above 80 miles an hour there, and so you can imagine hanging out in a metal tower built in the late 1930’s maybe not being the most pleasant way to while away your work day.

And then, later in the season, the wind dies down. We get towards June and July and into August, and there are days of just supreme silence, nothing but bird calls. So, I see that place in many different moods and weathers, and some I prefer more than others, but it’s kind of an interesting experience to see the range of moods and weathers in a place if you just root yourself there and sit and watch for awhile.

Brett McKay: Do you get bored up there? Like you’re just staring out thousands of acres, and you’re trying to … I mean, I’m sure … Does your mind wander? Like, what do you think about? What do you do to while the way the time?

Philip Connors: Yeah. People ask me that a lot, and it is just the case that I can’t remember a moment there when I was ever bored. The view is so interesting for one thing. There’s plenty to do just from a logistical perspective. You know, I wash my clothes by hand and hang them on the clothes line. I chop wood for warmth because the nights get cold in April. It sometimes gets down into the teens, and so I need a fairly large stack of wood there every season. So, there’s also just facilities maintenance that I have to do: Painting, roof repair, keeping the gutters tight because they catch rainwater that filters into my cistern, and is my drinking water source.

And then it’s also the case I like to read and write. So, I’m blessed I have a job where if I look out the window every 10 or 15 minutes and do a 360 scan, I am pretty much performing the basics of my job, and I can multitask by tapping away on the typewriter or reading a book in the tower and just staying vigilant while I’m doing that, toggling back and forth between these activities.

So. there’s plenty to see, plenty to do and enough to keep me busy that I can’t remember a time where I thought, “Yeah, I wish I were not here. I wish or were somewhere else where there was more stimulation,” because there’s plenty enough for me there.

Brett McKay: Have you noticed that your writing changes when you’re up there or is it pretty much the same?

Philip Connors: Yeah, it interesting because I use different tools at different times, and I think that does affect the writing. Over the years, I’ve done a lot of writing by hand there in notebooks, and I’ve also done a fair amount of writing on an old Olivetti Latera typewriter, and that feels different than when I come home and use my laptop. And I think it’s good for me actually because, especially the longhand, slows me down, and I really treasure the ability to actually work and think that way because it seems like most of the pressure in our culture is to do everything faster, and I just find I’m a slow thinker, a slow talker, as you’re probably finding in this interview, and I think better and more clearly if I slow things down, and it’s not a luxury most of us have in our jobs, I don’t think anymore, but in mine, I have that luxury, and I try to cherish it and use it to the best of my ability in my writing to maybe give a different flavor to my writing then you might find elsewhere.

Brett McKay: So, another thing you do, you wrote like an addendum to your first book, Fire Season, at least about you listen to baseball games on the radio. Tell us about the virtues of listening to a game via radio instead of watching it on TV.

Philip Connors: Yeah, it’s a habit for me that goes way back to my childhood growing up on a farm in Southern Minnesota where we were often working in the fields, in the tractor or working in the livestock barns, and we’d just have a game on the radio all summer long. So, it felt kind of natural to revert to that habit when I’m up there on a mountain and most of my connection to the outside world there happens aside from my VHF radio, which is a Forest Service Agency radio where we just talk business, it happens via FM radio and AM radio because I can pick up signals from long distance.

So yeah, over the years, I made a habit of tuning in games that I could find on the AM radio, often out of Denver or Phoenix, the Rockies, the Diamondbacks, and it kind of seems to fit with the throwback nature of the job. Yeah. Most people who geek out on baseball are watching it on television. Maybe they have the MLB Network package or whatever, and I certainly enjoy doing that from time to time, but I have always liked having a picture painted in words for me and imagining the game playing out in my head because it takes me back to the late 70’s in southern Minnesota where I would stay up late with a radio under my pillow listening to Twins games on the West Coast after I was supposed to be in bed. Just one of those delightful, a kind of antiquey things about our culture that you can thankfully still do.

Brett McKay: You can still do. Yeah, I listen to football games on the radio and yeah, it’s mentally or cognitively taxing because it’s not something … You have to imagine, with your brain, without seeing it, what’s going on based on what some guys describing, and that can be hard.

Philip Connors: Yeah. I think it’s a more active, mental experience than watching on TV. TV seems to allow you a passively because it’s just coming at you in images. Whereas, if you’re listening, you’ve got to create the images. They’re not there right in front of your eyeballs.

Brett McKay: So during these 16 years you’ve been watching fires, have you ever seen a massive wildfire on the Gila?

Philip Connors: Yeah, more than one. Really, starting in about 2011, we started to see larger fires. In 2012, I witnessed the largest fire in New Mexico state history, which was more than 500 square miles, almost 300,000 acres, burned up, most of a very large mountain range. And then the very next year, I had an experience where a similar fire, about half as large, burned most of the mountain range where I work and forced me to flee in a helicopter evacuation because it was clear that the fire was gonna burn over my mountain and all around it. So, I saw it when it was a single tree struck by lightning, putting up a little puff of white smoke, and then I watched from afar. I was actually re-reassigned to a different tower 20 miles away for the rest of the season and watched as it burned all around my mountain.

So, we’re seeing mega fires now on a scale we have not seen before certainly in recorded history anyway.

Brett McKay: What has been your biggest takeaway about life in the wilderness working the firewatch all these years? I mean, you’re coming on two decades of doing this.

Philip Connors: Oh, the biggest takeaway is probably that the healthiest land is the land with the least human impact to it. The Gila is a mix. Much of it is grazed. A lot of it has roads through it. Some of it as mining claims on it. There are very small human settlements here and there. And yet a lot of it is roadless wilderness where you can only travel by horseback or on foot, and the further you go into that part of the landscape, the wilder it is, the healthier it feels, the more wildlife you experience.

And I just love being out there because it’s so beautiful to experience that web of life that’s been existing there for millennia. It can be a challenge to come down off the mountain and drive back into a city like El Paso where I live now and see what we’ve done to the landscape there because it’s an urban planning catastrophe. We’re chewing evermore into the desert with new housing developments, and it’s a stark contrast to the beauty and complexity and biodiversity of a place like the center of the Gila wilderness, which feels probably about like it did when it was inhabited by the native culture a thousand years ago. And I love the feeling of being in that landscape, and I cherish it more and more all the time because it seems to be under threat everywhere, those types of landscapes.

Brett McKay: If there was someone listening to this podcast and they think, “I want to do that. I want to be a firewatch.” Are these jobs pretty competitive since there are so few of them now?

Philip Connors: Yeah, they’re extremely competitive. As mentioned, I’ve been doing it for 16 years, and I’ve found that I’m still the rookie in the Gila because all my colleagues started before me and have kept at it for, in many cases, decades. I have one colleague who, the upcoming season will be her 37th year, 37th and 38th, I can’t remember. Another colleague who’s been at it for 29 years.

So, once people get these jobs, they do find it hard to give up because they’re so precious and so groovy, and there just aren’t very many of them, and the ones that do open up, the battle for them as sort of competitive, and the Forest Service has a program where it privileges those with military experience. So, you have hiring preference if you’re coming out of a military background.

So, if you have that, you have an advantage in those jobs that do open up, but you have, just because there’s a few hundred of us and most of us are clinging to the jobs we have, it does make it really hard to break in.

Brett McKay: Well Philip, is there some place people can go to learn more about your work?

Philip Connors: Yeah. I have a website, www.philipconnors.com. I have some links there to my books and my other work, including photos from my location, so that’s a good place to start and branch off from there.

Brett McKay: Well Philip Connors, thanks for you time. It’s been a pleasure.

Philip Connors: Oh, the pleasure was mine. Thanks for having me on the podcast.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Phillip Connors. He’s the author of the book, Fire Season, Field Notes from a Wilderness Lookout. It’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about his work at PhilipConnors.com. Also, check out our show notes at aom.is/firewatch where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM Podcast. Check out our website, artofmanliness.com where you can find thousands of thorough, well researched articles about social skills, physical fitness, barbell training, personal finance, just life in general. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. It helps out a lot, and if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it.

Thank you for your continued support, and until next time, this is Brett McKay, encouraging you to not only listened to the AOM Podcast, but put what you’ve learned into action.