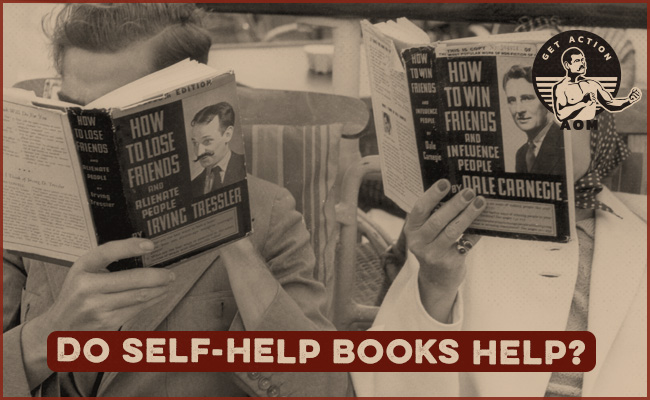

Self-help books — which aim to help individuals independently improve some or all aspects of their lives — have a long history. In the 19th century, such literature focused on strengthening one’s character. Classics of the early 20th century like Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends & Influence People offered advice on how to be more likeable. In recent years, self-help books have proliferated on topics like forming habits, reaching goals, losing weight, increasing productivity, overcoming anxiety, and generally living one’s best life.

The popularity of “bibliotherapy†has only grown over the last decade, with sales of self-help books reaching over 18 million annually in the United States alone. You’ve probably picked up a self-help book, or several, over the past year.

The demand for self-help books isn’t hard to understand: life can be confusing, frustrating, and obstacle-ridden, and yet also full of potential and possibilities. People are thus hungry for guidance on how to surmount the former and seize the latter. They want to better themselves.

But hovering over this quest is a question that’s rarely asked: Do self-help books actually help?

(When) Do Self-Help Books Help?

Given that a lot of self-help books are written by academic psychologists, you might think they wouldn’t pump them out so voraciously unless there was real research backing up the idea that such books actually help people improve and change their lives.

But you’d be wrong on that count. In fact, very little research exists on the efficacy of self-help books overall, and in some areas of the subject, no studies have been conducted whatsoever.

The one primary research paper to have been done on the question of the helpfulness of self-help books was authored by Dutch social scientist Ad Bergsma. Entitled “Do Self-Help Books Help?” the paper explores what we do and do not know about whether bibliotherapy really works. Bergsma concludes that it can, but likely only when the following criteria are met:

When the book is problem-focused. While the themes of self-help literature run the gamut from improving relationships to becoming more productive, Bergsma says they can be roughly categorized into two types: problem-focused and growth-oriented.

Problem-focused self-help books offer advice on how to overcome specific issues like insomnia, stress, addiction, anxiety, and depression.

Growth-oriented books focus on broader, more holistic topics like finding happiness, discovering your purpose, setting goals, developing your career, and improving relationships.

In the case of problem-focused self-help books, empirical evidence does exist which demonstrates their efficacy. For example, in a meta-analysis on bibliotherapy’s effectiveness in treating depression, researchers concluded that reading books on the subject can be just as effective as individual or group therapy. Similar studies have found that there are similar benefits to reading self-help books in order to treat anxiety and mild alcohol abuse.

When it comes to growth-oriented self-help books, however, no empirical research (amazingly enough) has yet been done on their efficacy. That doesn’t mean they don’t work, but as Bergsma says, you have to look at other, more tentative pointers — outlined below — in order to assess whether reading a particular book is likely to have a positive effect.

When the book’s advice is sound and up-to-date. Many self-help books keep parroting advice that has become embedded in the popular culture, but has in fact been disproven by recent research. One example Bergsma gives of this phenomenon is the way many relationship books still push the idea that “active listening†is crucial in healthy relationships, despite the fact that “research shows that even happy, loving couples don’t use the technique.†(It’s fine to argue and fight as long as you have more positive interactions than negative ones.) Naturally, if a book is serving up bad advice, it’s unlikely to have a good effect.

When the book’s advice correlates with empirically-proven routes to happiness. There’s no empirical evidence to back the general efficacy of growth-oriented self-help books in achieving greater happiness, but there is empirical evidence to back the efficacy of certain behaviors and aims in achieving greater happiness, and when a book epouses these behaviors and aims, it is more likely to have a positive effect on the reader. As Bergsma explains:

If a self-help author recommends seeking happiness in a higher income, that advice is unlikely to work out well for most readers, since research has found little relation between happiness and income . . . If, however, the advice is to optimize personal relationships, an effective book has a good chance to enhance happiness, because good relationships appear to be an important condition for happiness.

When the book recommends looking not just at dreams but obstacles. Part of the potential efficacy of self-help books is the way in which they impart the message that anyone can change, anyone can get better. They’re a hedge against the paralzying passivity of learned helplessness. As psychologist Steven Starker observed in his book Oracle at the Supermarket: The American Preoccupation With Self-Help Books:

Of what value is an inspirational message to those in need of health, beauty, happiness, success, and creativity? In general, it lifts the spirit, engenders and supports hope, and keeps people striving towards their goals; it also fends off . . . hopelessness, despair, and depression. This constitutes [self-help books’] greatest service.

Yet the potential boon of hope that self-help books offer can also backfire, if this optimism is overly rosy and pie-in-the-sky, and not tempered with an honest, realistic assessment of the effort and obstacles that are required to reach one’s goals. Research shows that people who only concentrate on their dreams, and their attendant rewards, are apt to give up once they face some resistance en route to them. A good self-help book is thus one that both pumps you up, and splashes you with cold water.

When you’re already self-motivated. While research has shown that problem-focused self-help programs and books can be effective, that’s only the case when people actually implement and stick with the given recommendations. As Bergsma reports, “Self-help has greatest success with people with high motivation, resourcefulness, and positive attitudes toward self-help treatments.â€

This is incredibly unsurprising, but self-help advice of every kind only works when put into practice. If you’re already motivated to make a change, self-help books can give you an extra boost and some needed direction, amplifying a trajectory you’re already on. But if you’re turning to self-help books for motivation, they’re unlikely to deliver; you’d probably be better served by seeking external help — with its accompanying layer of accountability — than trying to do things entirely on your own.

How to Get the Most Out of Your Self-Help Reading

So self-help books can help. But their effectiveness depends on their alignment with the guidelines above. Here’s how to implement them, along with other tips for getting the most out of your own bibliotherapy:

Be discerning in the books you choose. Pick self-help books that are written by experts or drawn from the research of experts, epouse principles and aims that actually lead to happiness, and temper optimism with realism.

Manage expectations. A lot of self-help books make exaggerated claims about their benefits:

“Learn THE secret to losing weight and keeping it off forever!”

“Increase your confidence overnight!”

“Never be distracted again!”

That’s good marketing copy, but not realistic.

Most personal change is slow and hard. There will be setbacks.

Also, most personal change requires a multi-faceted approach. There are no silver bullets.

When people read a book that promises amazing results, but then fail to achieve those results, it could result in demoralization and learned helplessness. They start to think, “If this amazing book didn’t work, nothing will.”

For this reason, Bergsma recommends that as you read self-help books, you do so with realistic expectations. Don’t expect you’ll find an insight that will change your life overnight because that’s not how change happens.

Pick and choose what you implement; experiment. One of the flaws of self-help books, Bergsma says, is that they often take a one-size-fits-all approach to personal improvement. General advice doesn’t map neatly onto people’s varied particularities.

It’s natural to want someone to tell you exactly what to do. But, rather than looking to a self-help book for a step-by step blueprint to follow, Bergsma suggests using it the same way you would a travel guide:

Most readers will not follow [a travel guide] page by page, but will study parts of the book and will select some travel options they would have never heard of without the book. In a similar way self-help books . . . show options for thinking and acting from the psychological toolkit of the individual that are underdeveloped or could be used more often.

You don’t have to try everything you read in a self-help book. What works for someone else might not work for you and vice versa. Take what resonates with your unique personality, lifestyle, schedule, and limitations, and experiment with it. If something doesn’t work, stop doing it, and don’t feel bad about it.

Get action! This point can’t be hit home enough. It doesn’t matter how sound or research-backed the principles are in a self-help book; if you don’t put them into practice, they won’t work!

As Bergsma notes, this isn’t any different from a person getting help from a professional therapist. Therapists can offer their patient advice, but if the patient never takes action on the advice, they won’t make any progress.

Ultimately then, the effectiveness of self-help books depends primarily on the reader, leaving Bergsma to cheekily conclude: “if a self-help therapy works, we should first congratulate the ‘client’ not the ‘therapist.’â€