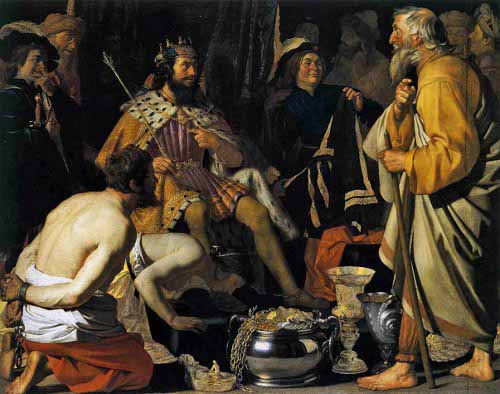

As Herodotus tells it, Croesus, the ancient king of Lydia, was once visited at his palace by Solon, a wise sage and Athenian lawgiver. The king was delighted to have the itinerant philosopher in residence, and welcomed him with warm hospitality. For several days, Croesus instructed his servants to show off the full measure of the king’s enormous power and wealth.

Once he felt Solon had been sufficiently awed by his riches, Croesus said to him:

“Well, my Athenian friend, I have heard a great deal about your wisdom, and how widely you have travelled in the pursuit of knowledge. I cannot resist my desire to ask you a question: who is the happiest man you have ever seen?â€

King Croesus was already certain that he was in fact the happiest man in the world, but wanted to enjoy the satisfaction of hearing his name parroted back to him from such a venerated sage.

But Solon, who was not one for flattery, answered: “Tellus the Athenian.â€

The king was quite taken aback and demanded to know how such a common man might be considered the happiest of all.

Tellus, Solon replied, had lived in a city with a government that allowed him to prosper and born fine sons, who had in turn given him many grandchildren who all survived into youth. After enjoying a contented life, he fought with his countrymen, bravely died on the battlefield while routing the enemy, and was given the honor of a public funeral by his fellow Athenians.

Croesus was perplexed by this explanation but pushed on to inquire as to who the next happiest man was, sure that if he wasn’t first, he had to be second.

But again Solon answered not with the king’s name, but with a pair of strapping young Argives: Cleobis and Biton.

Known for their devotion to family and athletic prowess, when their mother needed to be conveyed to the temple of Hera to celebrate the goddess’ festival, but did not have any oxen to pull her there, these brothers harnessed themselves to the incredibly heavy ox cart and dragged it over six miles with their mother aboard. When they arrived at the temple, an assembled crowd congratulated the young men on their astounding feat of strength, and complimented their mother on raising such fine sons. In gratitude for bestowing such honor upon her, the mother of these dutiful lads prayed to Hera to bestow upon them “the greatest blessing that can befall mortal men.†After the sacrifices and feasting, the young brothers laid down in the temple for a nap, and Hera granted their mother’s prayer by allowing them to die in their sleep. “The Argives,†Solon finished the tale, “considering them to be the best of men, had statues made of them, which they sent to Delphi.â€

Now King Croesus was livid. Three relative nobodies, three dead men were happier than he was with his magnificent palace and an entire kingdom of his own to rule over? Surely the old sage had lost his marbles. Croesus snapped at Solon:

“That’s all very well, my Athenian friend; but what of my own happiness? Is it so utterly contemptible that you won’t even compare me with mere common folk like those you have mentioned?â€

Solon explained that while the rich did have two advantages over the poor – “the means to bear calamity and satisfy their appetites†– they had no monopoly on the things that were truly valuable in life: civic service, raising healthy children, being self-sufficient, having a sound body, and honoring the gods and one’s family. Plus, riches tend to create more issues for their bearers – more money, more problems.

More importantly, Solon continued, if you live to be 70 years old, by the ancient calendar you will experience 26,250 days of mortal life, “and not a single one of them is like the next in what it brings.†In other words, just because things are going swimmingly today, doesn’t mean you won’t be hit with a calamity tomorrow. Thus a man who experiences good fortune can be called lucky, Solon explained, but the label of happy must be held in reserve until it is seen whether or not his good fortune lasts until his death.

“This is why,†Solon finally concludes to Croesus, “I cannot answer the question you asked me until I know the manner of your death. Count no man happy until the end is known.â€

Croesus was now sure Solon was a fool, “for what could be more stupid†he thought, than being told he must “look to the ‘end’ of everything, without regard for present prosperity?†And so he dismissed the philosopher from his court.

While the king quickly put Solon’s admonitions out of his mind, the truth of it would soon be revealed to him in the most personal and painful way.

First, Croesus’ beloved son died in a hunting accident. Then, blinded by hubris (excessive pride), he misinterpreted the counsel of the oracles at Delphi and began an ill-advised attempt to conquer King Cyrus’ Persian Empire. As a result, the Persians laid siege to his home city of Sardis, captured the humbled ruler, and placed him in chains on top of a giant funeral pyre. As the flames began to lick at his feet, Croesus cried out, “Oh Solon! Oh Solon! Oh Solon! Count no man happy until the end is known!â€

Count No Man Happy Until the End Is Known

What did Solon mean by his seemingly cryptic statement?

Can a fulfilled life truly only be measured after all is said and done? This seems to fly in the face of modern Western thought. We see happiness as a subjective mood, a feeling that can fluctuate from day to day and be boosted by a pill or a bottle or a romp in the hay. For the ancient Greeks, however, happiness was encapsulated by the concept of eudaimonia, a word we do not have a modern equivalent for, but best translates as human flourishing. Happiness was not seen as an emotional state, but rather an assessment as to whether a man had attained virtue and excellence, achieved his aims, and truly made the most of his life. A man’s life might start well, and continue in prosperity through middle age, but if it ended poorly? His eudaimonia was not complete.

Thus, Solon was not arguing that men like Tellus and Biton were happier in death than in life; he was not referring to the afterlife. Rather, he argues that a man’s happiness can only be measured by a full accounting of it from start to finish, a measurement that cannot be taken until after he draws his last breath.

“Whoever has the greatest number of the good things I have mentioned [family, health, sufficiency, honor], and keeps them to the end, and dies a peaceful death,†that man, Solon argues, “deserves to be called happy.†Simply living a long life or attaining fine things does not make one happy; happiness is a label solely reserved for he who “dies as he has lived.â€

The truth of this observation was not only lived out by Croesus (although his “end†upon the pyre was ultimately postponed by the mercy of Cyrus who decided to spare his life, and by the god Apollo who put out the flames), but in the lives of more modern men as well.

Ulysses S. Grant achieved one of the greatest degrees of success a man can possibly hope for: winning a war and then the White House. But after the presidency, he invested almost all of his assets in a banking firm his son had founded with a partner. The partner turned out to be a swindler, the firm went belly up, and Grant was left destitute, forcing him to sell his Civil War mementos to repay his loans. That same year, Grant, who had long had a habit of chain-smoking cigars, was diagnosed with throat cancer. In an attempt to pay off his debts, he worked on writing his memoirs until his death at age 63, only one year later.

William C. Durant became incredibly wealthy as he moved from lumberyard worker, to door-to-door cigar salesman, to founder of both General Motors and Chevrolet. Durant became a mover and shaker on Wall Street during the 1920s, and in the aftermath of the crash of ’29, though his friends advised against it, he joined with Rockefeller and others in buying large quantities of stock to shore up public confidence in the market. Durant subsequently lost his shirt and became bankrupt at age 75. A stroke in 1942 weakened his physical and cognitive abilities, and he lived out his days managing a bowling alley in Flint, Michigan until his death five years later.

Most recently, Joe Paterno could not more clearly embody Solon’s admonition to count no man happy until the end is known. For decades Paterno was revered as not just a football coach, but as an upstanding mentor who emphasized the importance of character to his players. Students bought shirts with his name emblazoned upon them and a statue of his energetic likeness was erected on the Penn State campus. But a luminous half-century long career ended not with adulation and fanfare, but a dismissal for his role in the Sandusky sex abuse scandal. He died two months later of cancer. A posthumous investigation heightened the blame for his role in the scandal, erased his record of achievements, crippled his beloved football program, and resulted in the removal of his statue. Truly, a tragedy of Greek proportions.

Four Lessons from the Tale of Solon & Croesus

Solon’s counsel may sound rather bleak – no one wants to think about the fact that each day could bring disaster and ruin our happiness – but Croesus’ cry of “Oh Solon! Oh Solon! Oh Solon!†has come to me quite often since hearing Herodotus’ tale, and has served to remind me of several important truths:

Don’t take things for granted. Solon’s forecast for life may be gloomy, but it’s realistic. Nobody knows if the things they enjoy today might be taken from them tomorrow. It’s important to be grateful for what you have each day – soak it in, make the most of it, don’t leave things unsaid and undone.

Focus on what matters most. Unfortunately, some of the wealthy concentrate on their riches to the exclusion of everything else. And yet, money can be so fleeting and contributes so little to “the good lifeâ€; if it disappears, they are left with nothing else from which to draw satisfaction. Solon argues that the man who dies with the most “things†that truly matter — self-sufficiency, health, virtue, family, piety, honor — is happiest. Concentrate on the things which last – that which remains after all else passes way.

Stay vigilant and beware of pride. Some calamities come to us by chance – disease and accidents can cause unforeseen reversals in our fortunes. We can only prepare for them by living providentially in our finances and cultivating the virtues of resiliency and calmness. But oftentimes, a man’s downfall could have been prevented through vigilance and humility. When men like Tiger Woods and John Edwards reflected on their downfall post-scandal, both said they had gotten to the point where they no longer believed the ordinary rules applied to them. When men become successful, they often get sloppy in their decision-making, less circumspect about with whom they associate, and indulge in vices that lead to ruin. A man who seeks eudaimonia can never afford to let down his guard.

Endure to the end. As soon as you think you’ve “made it,†you’ve already begun to decline. It’s easier, and a great deal more fun, to find success…much harder to maintain it over the long haul. But there’s no coasting in life – you’re either moving forward or backward. To attain happiness, a man must follow Solon’s counsel to look to the end, while also having the discipline to do the dull, unglamorous day-to-day tasks required to reach that end.