A lot of ink has been spilled over the past several years about the dismal financial situation that Millennials (individuals born roughly between the early 1980s and late 1990s) find themselves in. Statistics show that my generation is debt-laden, underemployed, and has less money than our Baby Boomer parents did at the same age.

Articles written about the financial woes of Generation Y tend to follow one of two pervading narratives:

1) Millennials are lazy, entitled narcissists who have brought their problems on themselves by not being ambitious, hard-working, and independent enough.

Or

2) Millennials came of age during the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression (caused by the hubris of entitled, narcissistic Baby Boomers, of course), are saddled with massive student loans, and thus have the deck impossibly stacked against them. (And if they are a little coddled, well, who raised them to be that way?)

The first narrative places the blame solely on Millennials, while the second largely extricates them from any culpability.

While these tidy explanations might make for good click-bait, and the satisfying disgorging of righteous indignation, like all narratives, they leave out a lot of nuance for the sake of a good story.

And, they miss some important (and more hopeful) possibilities.

Generation Y does have the deck stacked against it. But that can be both a curse and a blessing.

In fact, rather than being a crop of peers who will be remembered for their indolence and indulgence, Millennials could very well be the next Greatest Generation of personal finance.

The Great Depression, the Great Recession, and a Generational Cycle Turned Round

According to the Strauss-Howe theory of history, similar geopolitical and economic events, as well as generational archetypes, repeat themselves roughly every 80 years.

Within that 80-year cycle (or “saeculumâ€) are 20-year mini-cycles (or “turningsâ€) which each witness distinct sets of events as well as cultural moods. They are most easily thought of like the seasons of the year: The first turning (“springâ€) is a “High†period in which institutions, optimism, unity, and progress are strong. The second turning (“summerâ€) is the “Awakening†period, which seeks a rejuvenation of the inner worlds of art, religion, and values. The third, “fall,†is called the “Unraveling,†as the culture fragments and institutions become dysfunctional. The fourth turning is a historical winter — a “Crisis†period in which there is typically economic turmoil and war. Then, spring comes once more.

Moving through these four seasons are four generational archetypes (Artist, Prophet, Nomad, and Hero) whose characteristics are shaped by the turning they pass through as they come of age. For example, during a fourth turning, those of the Artist generation are little children, those of the Hero generation are young adults who serve as “foot soldiers†in the fight, middle-age Nomads lead Heroes, and older Prophets impart vision and values for navigating the Crisis.

The last Crisis began in 1929, ran through the 1940s, and was driven by the Great Depression and WWII. The young adults who grew up in financial straits and fought the war on the ground were the last Hero generation.

Over the past eight decades the wheel has spun round once more, so that we again find ourselves in a fourth turning. This one, according to Neil Howe, co-formulator of the generational cycle theory, began with the financial crisis of 2008.

The cohort coming of age during this Crisis period are, of course, Millennials, who find themselves in the position of being the new Hero generation.

Seeing Gen Y as “heroic†may seem like quite a stretch to some. But as Howe pointed out in my interview with him, “Remember that no one said anything about the GIs being the Greatest Generation until the very end of the last fourth turning.†No one thought the last Hero generation was anything special at the time either; it was only in retrospect, after they had fully risen to the challenge of their age, that they were venerated.

While the recession of 2008, the effects of which continue to linger on, wasn’t as severe as the Great Depression, it has still proved a significant economic challenge to Millennials — one that may ultimately inculcate the same kind of responsible values and solid frugality their grandparents became so famous for.

The Economic “Big One†Millennials Are Facing Down

It can be easy to minimize the economic challenges Generation Y has been burdened with; certainly some pundits have chalked up our financial problems to unresilient bellyaching.

But the reality is that Generation Y is facing an uphill economic climb. Here’s the not-so-rosy lay of the land:

Millennial income is stagnant…The recession of 2008 not only hit Millennials hardest, but the recovery has benefited them least. Research shows that they’re still earning as much as 20% less than both Baby Boomers and Gen Xers did at the same age.

For young men especially, inflation-adjusted wages have been falling since long before the 2008 recession, beginning their decline in the 1970s. This deterioration in well-paying jobs has led to less and less male participation in the workforce. In 1960, 80% of men ages 18-34 were employed; today, that number is just 71%

…and will likely remain stagnant for two decades. According to research done by Lisa Kahn at Yale University, the negative financial effects of coming of age during a recession aren’t just short-term, but rather remain stubbornly persistent and can last up to twenty years. As an article on the study explained, men who graduate from college during an economic downturn “earn 6 to 8 percent less in their first year on the job for each percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate.â€

Men who graduate during an economic boom time are able to get hired to a higher-level, better-paid job right out the gate, and this positions them for steady progress up their desired career ladder. They get more opportunities to improve their skills and more experience in their profession right from the get go, and when they make raises and bonuses, the increases are based on their higher original starting salary. It becomes a positive feedback loop.

The unlucky men who graduate during an economic downturn, on the other hand, not only make less money from the start, but over the next two decades, they end up making an average of $100,000 less than those who graduate at more opportune times. Theirs is a negative feedback loop: having graduated in a tight job market, they are more likely to be forced to take a lower-level, lower-paying job, that’s often unrelated to their desired career path. Unfortunately, even when/if these detoured folks later do get back on track, they’ve already fallen behind in their field, and the raises they earn are smaller, because their original starting salary was smaller.

The psychological effect of coming of age during a recession also dampens an individual’s economic prospects. Those who graduate during a downturn tend to be more risk-averse, so that even as the economy recovers, they’re more likely to hold on to their current job and less apt to look around for possibly better and higher-paying opportunities.

Millennials are laden with debt. Thanks to skyrocketing education costs, Millennials are beginning adulthood as one of the most debt-burdened generations in American history. The debt of graduates doubled between 1996 and 2006, and an average college-educated Millennial starts adulthood with an albatross of $35,000 worth. That number can increase several times over if they went to a private school or pursued a post-graduate degree.

According a survey conducted by PwC, student loans not only drag down Millennials’ finances, but also weigh on their psyches: 54% are concerned about their ability to repay their debt.

Members of Generation Y took on that debt in the hopes of converting their degree into a well-paying job; instead, many crossed the graduation stage to enter the worst recession in eighty years. While the statistics show that, in the long-run, a college education still significantly increases earning potential, beginning life with that much financial baggage has prompted many Millennials to postpone life goals like getting married or buying a home.

Millennials are financially dependent on parents. Despite being in their 20s and 30s, many Millennials still rely on their mom and dad for housing and other necessities. Recent data from Pew Research shows that more young adults ages 18-35 (including a full 35% of young men) are living with their parents than at any time since the 1940s.

Millennials are financially fragile. With stagnant income and heavy debt, many Millennials lack a financial safety cushion. According to a Washington Post survey, 63% would have difficulty covering an unexpected $500 expense. In the survey conducted by PwC, nearly 30% of Millennial respondents reported that they were regularly overdrawing their checking accounts, suggesting they’re falling short of even living paycheck to paycheck.

Because not all members of Generation Y can rely on financial help from their parents, more and more are turning to alternative financial services like payday loans and pawn shops to cover unexpected expenses. While the heaviest users of such services are individuals with a high school degree or less, even college-educated Millennials are increasingly using payday loans to get by.

Upward economic mobility is decreasing. Research last year by a team of economists led by Stanford University’s Raj Chetty found that people born in 1950 had a 79% chance of making more money than their parents. That figure has steadily slipped over the past several decades, such that those born in 1980 had just a 50% chance of out-earning their folks. Economists suggest that declining economic mobility is due in large part to a decrease in the absolute value of a college degree. Median earnings are lower for Millennial college graduates than they were for Generation X grads, even though the cost of a college education has skyrocketed.

Hopeful Signs of the Emergence of a New Heroic Personal Finance Generation

Given the daunting challenges outlined above, some Millennials have reacted with pessimism, hopelessness, and even bitterness towards the older generations who have bequeathed this pockmarked economic landscape to us.

But while no one would surely wish to come of age during an economic downturn, being forced into such a position is not without some conciliatory advantages.

While many have long admired the way members of the Greatest Generation embodied values like responsibility, foresight, and thrift, they weren’t made out of an inherently different, better, stock than us. Rather, they were simply shaped by circumstances that brought forth these virtues — they lived through a particularly difficult period of history, and rose to meet the challenges thrust upon them.

My fellow Millennials have been presented with a similar opportunity, and there’s already emerging evidence that it’s likewise shaping us in a backbone-strengthening way.

Millennials are savings more than other generations. 66% of Generation Y men describe themselves as savers, and a recent survey by Bankrate shows that Millennials are walking the walk and actually saving more than other age groups. Fewer young people ages 18-29 report saving nothing, while more Millennials say they’re saving up to a tenth of their income, compared to older age groups. And keep in mind, they’re saving more despite the financial challenges that are hitting this generation particularly hard.

According to another study, half of Millennials report that they’ve started to save for retirement (and almost half of these savers are socking away at least 6% of their income). The most popular reason these savers gave for doing so, was that “they realized starting early can result in a bigger nest egg down the road.â€

While half may not seem like much, the number seems quite healthy when contrasted with the fact that 40% of Baby Boomers — who are several decades closer to actually retiring — still haven’t saved anything for retirement.

According to Bankrate’s chief financial analyst, Greg McBride, “Millennials have a greater inclination toward saving, for both emergencies and retirement, than we’ve seen from previous generations.â€

Millennials are more careful about credit card debt. Members of Generation Y may often regret the amount of debt they took on to pay for college, but the experience of that burden has seemingly chastened them about taking on other kinds of debt. While household debt increased overall (and now sits at $12.29 trillion) in 2016, according to the Federal Reserve, the percentage of Americans under 35 who are carrying credit card debt has fallen to its lowest level since 1989. As an analysis of this data by the New York Times noted:

“for no other age group has the decline in the proportion holding credit card debt been more rapid than it has been for young Americans…Only 37 percent of American households headed by someone aged 35 and under held credit card debt in 2013, the most recent year for which data from the Survey of Consumer Finances is available, down by nearly a quarter from immediately before the financial crisis.â€

Millennials are also taking out less car and mortgage loans, a sign that points to their struggle with getting ahead, but also a commitment to living within their means.

The NYT article notes that it’s not only college debt that has made young adults wary of credit cards, but seeing family members and friends misuse them and suffer the consequences, especially when the recession hit. As David Robertson, publisher of The Nilson Report, a newsletter that tracks the payment industry, told the NYT: “It’s pretty clear that young people are not interested in becoming indebted in the way that their parents are or were.â€

Millennials themselves who were interviewed for the piece seconded this explanation, expressing the desire to avoid the temptation to use their money irresponsibly. Said one, “I don’t want to go out and buy, buy, buy, even though that’s what society wants me to do. I want to save and invest for the long term.â€

Millennial entrepreneurs have a committed, long-term, legacy-minded view of their business. Members of Generation Y are often knocked for being flighty. But according to a survey done by Wells Fargo, Millennial business owners want to build something that will last, and are more likely than older business owners to say they hope to pass down their business to their children one day, despite the fact that many of the respondents don’t even have children yet. Only 20% were hoping to sell their biz in order to move on to something new.

Millennials are less interested in traditional status symbols. Unlike their Generation X and Baby Boomer predecessors, Millennials aren’t as keen on spending money on traditional status symbols like cars, big homes, and designer clothing. For example, they’re 29% less likely than Gen Xers to buy a car. What’s more, the brands of those traditional status symbols aren’t as important to them either, and they don’t like logos on their swag.

Members of Generation Y are also finding cheaper ways to entertain themselves like staying home to watch Netflix (which only costs $8.99 a month) and cooking a homemade meal they found on Pinterest.

Overall, Millennials are happy with what they’ve got; 9 in 10 say they currently have a sufficient amount of money.

In other words, modesty and thrift have become cool again.

Will Millennials Become the New Greatest Generation of Personal Finance?

Where we are in the current fourth turning roughly parallels (turnings can be longer/shorter; slower/faster; less or more severe) 1937-1939 of the last one. (It’s worth noting that while production, profits, and wages had recovered to pre-1929 crash levels by 1937, this period saw another plunge back into recession). By this time, many young adults had made great sacrifices — being farmed out to live with relatives, quitting school to take jobs to support their family, joining the Civilian Conversation Corps to blaze trails and lay roads to earn pay that was all sent back home. Today’s “Hero†generation hasn’t had to give up as much, and truth be told, there still probably remains too many pockets in our ranks of those who have chosen to deal with economic challenges with fruitless whining and blame.

But then, our recession has not been as severe, less has been asked of us, and fewer opportunities have been given to step up and serve like the CCCers of old. So too, there are less cultural mores these days that dictate a stoic and resilient approach to hardship.

Yet, though the circumstances differ, and a resolute response has been more muted, I am hopeful that my generation will use our challenges not as an excuse for cynicism and apathy but as a chance to restore soberness and maturity to our personal finances, as well as the economy as a whole. There are signs we’re already moving in that direction, and we can accelerate that movement by intentionally choosing to deepen our commitment to these (re)emerging values.

Because ultimately, while the Greatest Generation’s commitment to prudence and frugality was born from the conditions forced upon them, the way in which they shouldered these burdens, rather than being crushed by them, was a matter of choice. Virtue doesn’t automatically come from necessity, but virtue can be made from it.

Despite the economic challenges they face, Millennials remains stubbornly optimistic about the future. As one study found, 67% “believe they will achieve a greater standard of living than their parents†and 72% “say they feel in control of their future and believe they can achieve their goals.†(It should be noted that Strauss and Howe predicted this characteristic optimism of Generation Y more than twenty years ago.) That may sound naive, but they actually have great reason to hold such hopes. If the Strauss-Howe theory turns out to be true, and if we are able to navigate successfully through this Crisis period, in about a decade or so we’ll find ourselves in the midst of another High. An economic boom period like the 1950s that the last Heroes enjoyed after twenty years of hardship and strife.

That doesn’t mean though that we should just sit on our hands and wait for 2028 to roll around. Developing and deepening a commitment to the principles of sound personal finance now will not only help us weather the current storm, but prepare us to deal with what is in many ways an even greater challenge: robust prosperity.

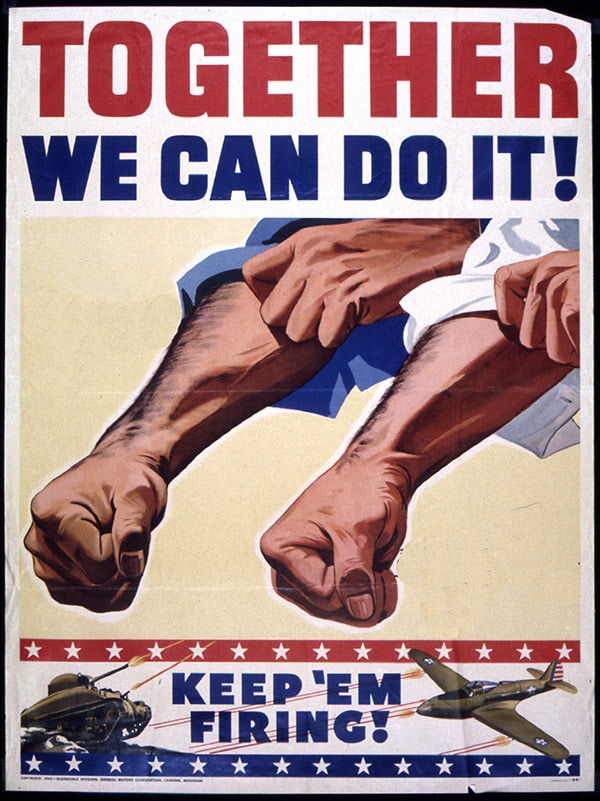

Next month we’ll lay out suggestions for how our generation can do just that, and surmount the challenges laid out above. ‘Til then, keep living simply and saving your dollars, and remember the motto that helped our grandparents endure their winter, and advance towards spring: We did it before and we can do it again.