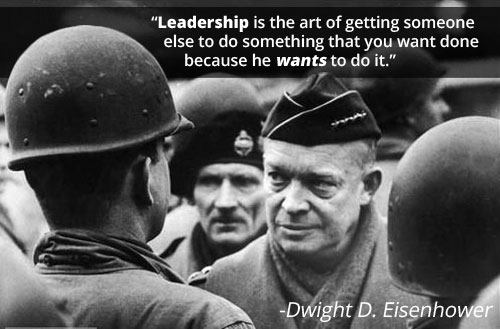

Dwight D. Eisenhower had unarguably one of the longest and most taxing leadership roles in American history. For two decades, the lives of thousands, sometimes millions, of people and the fate of great nations hung on his decisions.

As Supreme Allied Commander during World War II, Eisenhower oversaw the greatest amphibious assault in history, organizing the largest air and sea armadas ever assembled and commanding 160,000 men in the momentous Operation Overlord.

After the success of that mission helped bring the war to a close, Eisenhower dreamed of going home to a happy and peaceful retirement. Instead, he went on to serve in five more globally pivotal positions: Head of the American Occupation Zone in Germany, Chief of Staff, president of Columbia University, Supreme Commander of NATO, and President of the United States of America.

In each position, Eisenhower achieved great successes and also made mistakes. But whether he was navigating setbacks or achieving triumphs, he led. A self-described “simple Kansas farm boy,†his humor and congeniality—along with that famous lopsided grin—hid a keen and curious mind, an unyielding work ethic, and an ironclad sense of self-confidence. That confidence allowed him to stand tall with the weight of the world on his shoulders and boldly make critical decisions. The word his associates most often used to describe him was trust; people trusted Ike to make the right choices and shoot straight with them. His dedication to principle and his bounding vitality could inspire people to lofty visions, while his aw-shucks humility created a feeling of friendship and intimacy even with those he had never met. These qualities and more won him the affection, loyalty, and admiration of those who served both under him and over him.

“Morale is born of loyalty, patriotism, discipline, and efficiency, all of which breed confidence in self and in comrades…Morale is at one and the same time the strongest, and the most delicate of growths. It withstands shocks, even disasters of the battlefield, but can be destroyed utterly by favoritism, neglect, or injustice.” -DE

Truly, there is much to be learned from the life of Dwight D. Eisenhower, and so every other week for the next couple months, we’ll be taking an in-depth look at the many rock-solid leadership lessons that can be gleaned from his life, particularly his time in the military. While the rest of the articles in the series will be shorter, today we begin with a lengthier exploration of what was perhaps the cornerstone of Eisenhower’s success as a leader: his ability to build and sustain the morale of those under his command. Eisenhower worked his men hard each day, taught them not to cut corners, and pushed them to always do their best. At the same time, he listened to them, inspired them with his own example, and cared for them like a father.

Whether you’re a student body president, a corporate manager, or a coach, these principles will hopefully help you better inspire and bring out the best in those for whom you are responsible.

See and Care for Your Men as Individuals

“You must know every single one of your men. It is not enough that you are the best soldier in that unit, that you are the strongest, the toughest, the most durable, the best equipped, technically—you must be their leader, their father, their mentor, even if you’re half their age. You must understand their problems. You must keep them out of trouble; if they get in trouble, you must be the one who goes to their rescue. That cultivation of human understanding between you and your men is the one part that you must yet master, and you must master it quickly.†–Eisenhower in a speech to the graduating cadets at the Royal British Military Academy, 1944

Eisenhower loved life and he loved people. He believed in the latter’s strengths and was very sympathetic to their failings. Whether he was training a small unit or commanding thousands, he never saw the men as numbers, as push-pins to be moved across a map; rather, he always remembered that each man was an individual with hopes and aspirations of his own, with a family back home that loved him more than anything else in the world.

“I adopted a policy of circulating through the whole force to the full limit imposed by my physical considerations. I did my best to meet everyone from the general to private with a smile, a pat on the back and definite interest in his problems.â€

In order to keep this remembrance at the forefront of his mind, whenever he could Ike would slip away from his desk and the big shots who paraded through his office and make his way out to the front lines to meet with the men on the ground. He had a highly developed listening ability, and wherever he went he asked questions. He welcomed complaints, and if it was in his power, he worked to improve the situation. The men enjoyed meeting with the general, and Eisenhower always found himself rejuvenated by these conversations. “I belonged with the troops, he said. “With them I was always happy.”

In the months before D-Day, Eisenhower made these visits to the troops an even higher priority. He understood that once he issued the order for Operation Overlord to begin, he himself would become powerless; the success of the mission rested with the men who were storming the beaches of Normandy. If they bravely struggled through the Germans’ withering fire, the Allies’ aims would be achieved; if they cowered in the sand, the enemy would triumph. The level of the troops’ motivation could turn the tide.

And so, as June 6 approached, Eisenhower went out to meet as many of his men as possible, visiting 26 divisions, 24 airfields, 5 ships, and a dozen other military installations. He wanted as many of his sailors, airmen, and soldiers to see the man who would be sending them into battle as possible, and to personally speak with as many of his men as he could. When he arrived at a camp or airfield, he’d ask the men to break rank and circle around him. Then he’d offer some encouraging words, shake their hands, and talk to the men one-on-one. Eisenhower did not ask them just about their weapons or training as most generals did, but instead where they were from, what they hoped to do when they got home, and what life was like back in their home states.

Because Eisenhower was unwilling to let himself slip into seeing the men under his command as a faceless mass, their deaths pained him greatly. Some experts had estimated that the causalities of Operation Overlord could reach as high as 70%, and he could envision the news of those casualties reaching each man’s mother, father, wife. In the hours before D-Day was to begin, he was busy doing the job he thought most important to Overlord’s success: once again meeting with his men. He talked with and shook the hands of the paratroopers of the 101st Airborne, and then stood on the roof of the nearby headquarters to salute each plane as it took off en route to France. As the planes soared into the night sky, he thought of the dangers these brave men would soon be facing, and tears filled his eyes

The genuine tenderness Eisenhower felt for his men, and his acknowledgement of the very real, individual repercussions his decisions would cause, greatly increased his anxiety and the burden of his responsibilities. But while it wearied him, it also fueled the excellence of his leadership and the success of his command. Ike was the kind of commander both the men themselves, and their families, hoped they’d serve under. They knew that Eisenhower would not make a decision to send his men into battle if he had not thought long and hard about it and believed the action was absolutely necessary—that he would not play fast and loose with their lives, deciding their fate from inside an ivory tower.

A Leader Must Always Be Optimistic

Eisenhower was not only wearied by having to make decisions that would affect the lives of thousands of men—not to mention the fate of great nations—but also by the many logistical and political problems he had to grapple with every day in running a war. For a decade he worked 12-14 hour days, 7 days a week, keeping himself going with 4 packs of cigarettes and cup after cup of coffee each day. Very soon into that grinding schedule, Eisenhower “realized how inexorably and inescapably strain and tension wear away at the leader’s endurance, his judgment and his own confidence.†“The pressure becomes more acute,†he added, “because of the duty of a staff to present to the commander the worst side of an eventuality.”

But Eisenhower was committed to never revealing the strain he felt to others. Instead, he firmly believed it was necessary for a commander to “preserve optimism in himself and in his command.†“Without confidence, enthusiasm, and optimism in the command,†Eisenhower argued, “victory would scarcely be obtainable.â€

“I have developed almost an obsession as to the certainty with which you can judge a division, or any large unit, merely by knowing its commander intimately. Of course, we have had pounded into us all through our school courses that the exact level of a commander’s personality and ability is always reflected in his unit—but I did not realize, until opportunity came for comparisons on a rather large scale, how infallibly the commander and unit are almost one and the same thing.“

Eisenhower saw two powerful benefits to being a consistently optimistic leader. First, he was a big believer in the “act-to-become†principle; by acting hopeful around others, the “habit tends to minimize potentialities within the individual himself to become demoralized.” Second, it “has an extraordinary effect upon all with whom he comes in contact.†Reflecting on these benefits brought Eisenhower to a “clear realization:â€

“I firmly determined that my mannerisms and speech in public would always reflect the cheerful certainty of victory—that any pessimism and discouragement I might ever feel would be reserved for my pillow.â€

Never Esteem or Place Yourself Too Highly Above Your Men—on Whom You Rely

“In a war such as this, when high command invariably involves a president, a prime minister, six chiefs of staff, and a horde of lesser ‘planners,’ there has got to be a lot of patience—no one person can be a Napoleon or a Caesar.â€

While Eisenhower was the one man during the war who might have been tempted to put on Napoleon-esque airs, that was far from his style. He saw the whole undertaking as a team effort in which each person, from the lowly private to the Prime Minister, had a vital and indispensable role to play. His job was simply to fit the many disparate parts into one effective whole. It was a heavy job, but he did not feel it made him special. Eisenhower was a man of modesty and humility who hated being singled out for praise and loved to sincerely put the credit on others. It was “GI Joe,†who won the war, he said, not him.

Eisenhower believed that one of the things that destroyed morale was complaints of unfairness or injustice among the men—feelings that could be engendered by seeing that their leader did not give them enough credit and took too many privileges for himself.

“Humility must always be the portion of any man who receives acclaim earned in blood of his followers and sacrifices of his friends.â€

When Eisenhower was stationed in Italy, he took a cruise around the Isle of Capri with some colleagues. When they passed a large villa, he inquired as to whose it was. “Yours, sir,†someone answered. “And that?†Eisenhower asked, pointing to another stately villa. “That one belongs to General Spaatz,†was the answer. Eisenhower exploded: “Damn it, that’s not my villa! And that’s not General Spaatz’s villa! None of those will belong to any general as long as I’m Boss around here. This is supposed to be a rest center—for combat men—not a playground for the Brass!â€

These kinds of stories always got back to the troops, and helped win Eisenhower their affection and loyalty.

Keep Your Men Up and Doing

In 1918, during WWI, Eisenhower was assigned to run Camp Colt in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, with orders to “take in volunteers, equip, organize, and instruct them and have them ready for overseas shipment when called upon.†Because the men would go directly from the camp to a port to be shipped to the trenches of Europe, Eisenhower was “warned that no excuses for deficiencies in their records or equipment would be accepted;†when they left camp, the men had to be ready for battle.

The men were to be part of the newly-formed Tank Corps, and Eisenhower thought he’d get one group ready for a month, they’d ship out, and then a new group would arrive. But when the government put a temporary halt on shipping out any units except for infantry and machine gun battalions, none of the men at Camp Colt were called up, while new volunteers kept coming in. The number of men at the camp soon swelled to over 10,000, and Eisenhower worried about what all the waiting around would do to the men:

“Once they were competent in basic drill, they would have little to do. With time hanging heavy on the recruits’ hands we could be sure of one thing: morale would deteriorate quickly. I began to look around for a way to instruct the men in skills that would be valuable in combat and prevent the dry rot of tedious idleness.”

So without any orders from Washington, Eisenhower set up a telegraphy and motor school and obtained small caliber cannons on which to train his soldiers. He also got ahold of some machine guns and made the men get so familiar with them they could fire the guns from the back of a moving vehicle and could take the weapon apart and put it back together while blindfolded.

Later, although the brass had told him that the Tank Corps in Europe would have no need for men with training in telegraphy, the War Department requested 64 men with that skill; Eisenhower was ready to furnish them.

Give Your Men the Why Behind What You Ask Them to Do

Because Eisenhower made such frequent trips to the battlefront, he knew the challenging conditions his men were living and fighting under. And he knew that while duty and discipline were essential in keeping the men going, such things alone were insufficient in maintaining morale. There must also be a “deep-seated conviction in every individual’s mind that he is fighting for a cause worthy of any sacrifice he may make,†Eisenhower argued. In other words, the men needed to know the why behind their orders.

“You do not lead by hitting people over the head—that’s assault, not leadership.â€

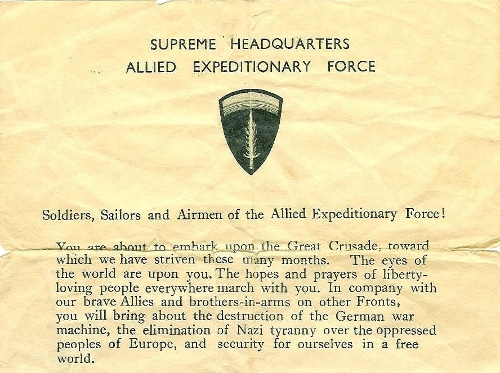

Eisenhower strongly believed that “In this war, more than any other in history, I think that we find the forces of evil arranged against those of decency and respect for human kind…We are on the side of decency, and democracy, and liberty.†And he asked his commanders to express this conviction to their men, to impress upon each individual soldier the idea that:

“The privileged life he has led is under direct threat. His right to speak his own mind, to engage in any profession of his own choosing, to belong to any religious denomination, to live in any locality where he can support himself and his family, and to be sure of fair treatment when he might be accused of any crime—all these would disappear if the forces opposed to us should, through carelessness or overconfidence on our part, succeed in winning this war.â€

You can see Eisenhower’s desire to only give his men orders, but the why behind their duty in the opening paragraph for his Order of the Day for June 6, 1944:

Leadership Lessons from Dwight D. Eisenhower Series:

How to Build and Sustain Morale

How to Not Let Anger and Criticism Get the Best of You

How to Make an Important Decision

Always Ready

__________

Sources:

Eisenhower: Soldier and President by Stephen E. Ambrose

At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends by Dwight D. Eisenhower