Sometimes I wonder what life would be like without the Internet. Firstly, I’d be out of a job. And after writing this series on reviving the trades, I romantically think about how fun it might be to become an electrician. The problem, when I think of this hypothetical scenario, is that I know nothing about electricity. I know how to read a power meter (perhaps there’s an AoM article about that in the future!), how to change a simple lighting fixture, and how to flip my breaker switches. I don’t know anything about currents, wiring, where my electricity actually comes from, etc. I’m obviously not qualified enough to just apply with the local electrician in town and expect to be hired. So if I actually wanted to pursue the dream of becoming an electrician, what steps would I need to take to become a tradesman?

Maybe you’ve had more serious thoughts about learning a trade, but you don’t know where to begin either. You may be a high schooler trying to figure out what to do with your life. Or you could be a nice middle-aged fella who’s been in a cubicle his whole life and wants to do something different. No matter the circumstance, let this article serve as your guide to starting a new career in the trades.

To get some help understanding the world of tradesmen and unions, I spoke with some experts in the field, including folks from Emily Griffith Technical College and Pickens Technical College here in Denver; I also spoke with the IBEW (International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers — the electrician’s union) and North America’s Building Trades Unions, which is a combo governing body and lobbying organization for 14 different building/construction-related trades.

First, Start at Home

If you’re thinking about the trades, take up a hobby (or a chore). Many blue collar jobs are actually things you can at least start out doing as hobbies/chores/household projects in the comfort of your own home or garage. Want to be a carpenter? You better know the basics of woodworking and how to operate power tools. Fancy yourself as a construction worker? Learn how to put up a wall in your unfinished basement. Do you see being a mechanic in your future? Tinker with your car, learn how to change your own oil . . . you get the picture.

You can learn the basics of anything online. While the trades require more hands-on skills than a lot of other jobs, there are textbooks and YouTube tutorials on any trade you may want to pursue. While not necessarily a must, knowing the basics of your trade will definitely give you an advantage when you start at a tech school.

Dipping your toes into the waters of trade work will also help you figure out if working with your hands is something you find satisfying, have a competence for, and want to pursue further.

The Path to Becoming a Tradesman

Although it may look a little different depending on the trade and even the state you’re working in, there is a general path to trades work that we can take a look at:

1. Have a high school diploma.

First, you need to graduate high school or have earned your GED. Without a high school diploma, there are very few jobs one can hold outside of retail and food service. Also important, although it may not seem like it, is taking the SAT or ACT. While those scores won’t be used for your entrance into a 4-year college, they can and will be looked at when applying for apprenticeships (more on that a little later). Particularly, math and science scores will be assessed, and although it probably won’t make or break your acceptance into a program, it could elevate you above other candidates in competitive fields and get you better apprenticeships.

If you’re lucky enough to attend a high school that offers shop class, take advantage of that opportunity. It will help you determine if you enjoy working with your hands, and give you a foundational knowledge of DIY work. Even if you don’t end up going into the trades, it’ll make you more handy as a grown man!

Just because you’re looking at blue collar work doesn’t mean you can slack off in high school. This rings especially true in dense metropolitan areas, where unions will have lines out the door for apprenticeship applications. You can bet in those instances that higher GPAs and test scores will set you apart.

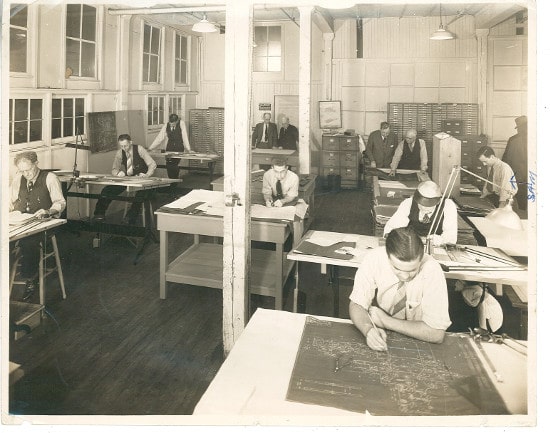

2. Receive formal training in your field.

After graduating high school, most tradesmen will attend some sort of schooling for a year or two, be it a community college or technical school. Community college is in many ways just a pared down version of a 4-year liberal arts school. You’ll get training in a specific field, but also often be required to take classes that aren’t related to your area of study in order to earn an associate degree. Community college will also cost more, as you’re getting those additional credits. With a technical school (also sometimes called trade school or vocational school), your training is dedicated entirely to your field of study. This often makes technical school a shorter program, and you’re only earning a certificate rather than a degree. In many cases that doesn’t matter with trade work, but it might be beneficial to get that associate degree for the sake of having a well-rounded education. It really just depends on your goals, educational desires, and budget as an individual.

While formal training like this may not be required for apprenticeships, these beginner’s courses will give you a leg up on other candidates (as mentioned above, especially in urban areas). In the plumbing world, for instance, you’d learn about water supply and drainage systems, as well as the basics of piping, fittings, valves, etc. If I was looking to become an electrician, I’d learn about currents, power grids, and how not to die by electric shock.

In more rural areas, or in places where there is a shortage of workers — such as the Gulf Coast — you may be able to go right from high school to an apprenticeship program. It may also be the case that an apprenticeship has a relationship with a local school, and you’d earn your associate degree through getting your work experience.

So while there are exceptions, this class work is highly recommended by employers and by unions and will get you better apprenticeships, which leads to the next and most important step for the aspiring tradesman…

3. The apprenticeship.

Apprenticeships are most often run by a local union chapter, but could possibly also be run by non-union contractors. The non-union variety are few and far between, so do your due diligence about the quality of the program if going that route (more on unions below). You can call your state’s labor department or even local tech schools to get more info about non-union certification/apprenticeships.

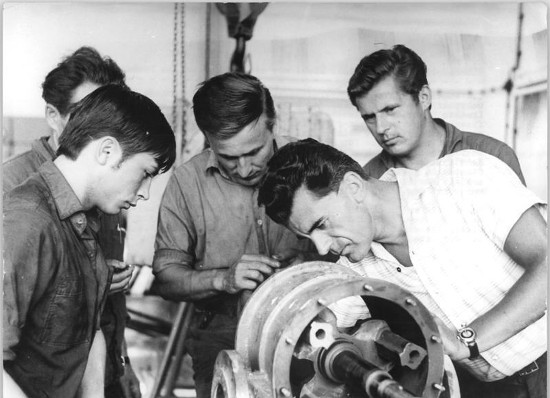

The apprenticeship phase of your trade career is 4-5 years of paid on-the-job training, as well as continued classroom work (which may or may not be paid). You’ll apply via a written application, as well as take an aptitude test (you can see why some formal schooling would be helpful). In most cases you’d be working under a Master tradesman, who would then sign off on your hours worked, allowing you to move into the next phase of your career.

During the apprenticeship, you can expect to start out getting paid about half of what you’ll make as a certified tradesman, and each year you’ll earn little bit more. In year one, this is often between $10 and $20 per hour. Not only is that a decent wage for someone just starting out in a career, these are years when many young men are attending a four-year college, and paying five figures a year to do so.

Listen to our podcast with Mike Rowe about the trades:

4. Becoming a Journeyman or Master.

You’ll have to complete a certain amount of apprenticeship hours before applying and testing to be a Journeyman. That title just means you’ve completed your apprenticeship, have passed a test on your skills and knowledge, no longer have to work under someone else’s license, and are then a certified tradesman.

In most trade fields, once you’ve spent 3-6 years as a Journeyman, you can work towards becoming a Master. This requires additional classroom training as well as a certification test. Passing the test and becoming a Master is much like the promotion from General Manager to Regional Manager – there’s better pay and benefits, but also more responsibility and people working under you. A Master Tradesman is often responsible for securing permits, designing systems and blueprints (rather than just implementing them), and training apprentices and Journeymen.

5. Find your niche and acquire more certifications.

Just as with white collar work, being a Mr. T (having a breadth of knowledge, but also an expertise in a single area or two) is beneficial to your career. With my electrician example, once I became a Journeyman, I’d likely find a specialty as a residential electrician, a research electrician, a hospital electrician, heck even a marine electrician is a possibility. The niches in the trades are endless, and once certified you’re sure to find something that calls out to you.

To recap, the path to becoming a tradesman is generally as follows:

- Earn a high school diploma (or GED)

- Take courses at a community college or technical/vocational school

- Obtain an apprenticeship, which will last for anywhere from 2 to 5 years

- Become licensed through a union or trade association, generally with the title of Journeyman or Master

- Continue to hone your skills and earn more niche certifications

Know that some of the trades do have shortened routes. For instance, to become an aircraft mechanic, you enter an FAA-certified school, get classroom and practical training for 1-2 years, take a test, and come away certified to work on airplanes. It’s a similar path for auto mechanics, as well as less technical trades like commercial painters. From there, as with most blue collar fields, you can earn additional certifications.

With so many trades and specializations out there, it’s important to do your own research on what your desired field of work requires. This is where Google comes in real handy; you can simply search for “How to become a …†and you’ll often get results straight from government regulation pages or union/trade organization pages. Mike Rowe’s website is another great resource for finding schools in your area, getting scholarships and financial aid, and contact information for trades organizations (don’t hesitate to call — all the folks I talked with were extremely helpful and delighted that someone wanted to talk about the trades!).

If You’re a Vet

If you’re a U.S. military veteran, you may have had (or are having) a hard time finding a job that fits you. You may not be up-to-date with changes to the modern workforce, or perhaps you just realized that being in an office isn’t what you’re cut out for. It was with those folks in mind that the non-profit organization Helmets to Hardhats was created. It seeks to connect vets with training, apprenticeships, and ultimately, long-term careers specifically in the construction industry.

What’s great about this program is that no experience or prior training is necessary. The military will cover all of that at no charge to you, and you can even use Montgomery GI Bill benefits to supplement your apprenticeship income. They also have a relationship with Wounded Warriors to provide these same opportunities to disabled vets.

Getting a Job: A Very Short Primer on Unions

Unions can be hard to figure out if you aren’t in one. Office dwellers likely only know of what they read in the papers, which is often politically driven. To clear some things up about how unions work, I spoke with Tom Owens from North America’s Building Trades Unions.

In about 3/4 of cases, tradesmen are part of a union. The ones who aren’t have found certification through another route, and have the freedom to work wherever they want and for how much they want — provided they can find that work, of course. While the merits of unions are hotly debated, they’re a reality of our work economy (no need to get into the pros and cons of unions here!). In most cases, there are truly benefits and downsides to being part of one.

The most basic definition of a union is that it is an organization that lobbies for its members’ pay, benefits, hours, working conditions, etc. They’re based around particular trades — electrical, construction, aircraft maintenance, etc — and negotiate directly with employers.

As noted above, most tradesmen have been certified through a union. Once your apprenticeship is complete and you’re certified, you can go one of two common routes: 1) use the union’s referral program to get placed at a job with a contractor or 2) be an entrepreneur and start your own business (in which case you’ll also likely receive union assistance with business training and support). If going the first route, as most do, your pay, benefits, work conditions, etc. are determined by what the union has negotiated. This is all put together in a contract called a Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA). These agreements will be for a set term, and then negotiated again once the term is up. When you see strikes in the news, it’s because a union and an employer can’t agree on the conditions of the CBA. Being in a union obviously takes away some autonomy, but independent research shows that most union workers make more money than they would striking out on their own. If you’re in a union, your path to getting a job will be fairly easy, especially if in a metropolitan area. If you live in a rural location, you may need to travel a bit to work. If you aren’t part of a union, you apply and pitch your merits and negotiate for jobs just like you would for an office position.

Another factor in determining whether to be part of a union or not is whether you work in a state with a Right To Work law. These laws, passed in 24 states, prohibit union security agreements. In layman’s terms, this means a union cannot require an employee’s membership in said union. For instance, if someone wants to work at a UPS loading facility and there’s a union in place, a Right To Work statute means that person doesn’t have to join the union in order to work at that job. In states without a Right To Work law, the union could have a provision in the CBA stating that all employees must be part of the union.

To see which states have Right To Work laws, click here. If your state doesn’t have this law on the books, it may be harder to find a job as a non-union worker, as unions/employers can pretty much require union participation (at least in terms of paying dues).

The waters are still a little muddy for me when it comes to unions, especially since each one has different bylaws, and there are various governing bodies as well. Readers, please feel free to add your insights and more info about unions (or your particular union) and how they operate in the comments.

Reviving Blue Collar Work Series Conclusion

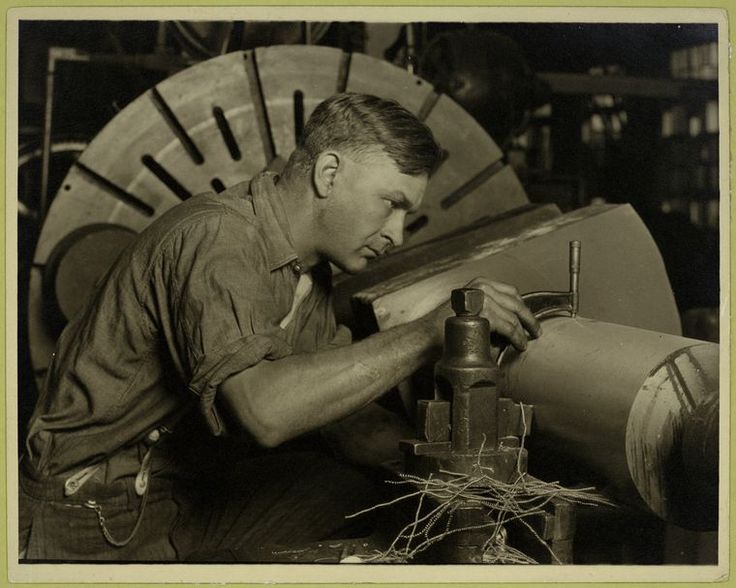

The quintessential American worker used to conjure up images of greased elbows, blue oxford work shirts, and bulky ironworkers with a hard hat on the noggin and hammer in hand. Today, it’s a skinny guy with a Mac in one hand and Starbucks in the other, driving to an office park full of cubicles. While that shift isn’t all bad, it’s certainly affected our culture in some negative ways. We’re fatter and more out of shape than ever before, we have more stress in our lives, we’re more bored at work and switch jobs more frequently, and in general people describe themselves as less happy than they did 50 years ago.

In today’s society, the diagnosis and solution to these ailments seem to take only one form: you must not be in the job you were “meant” to do, and everything will simply fall into place once you find your true passion. Yet while folks have been trying to follow this advice for several decades now, guys don’t seem any happier than they used to be.

It’s time to replace the endless and often fruitless search for one’s passion, with the search for satisfaction and fulfillment, and to acknowledge that it’s quite possible to find those rewards outside of white collar work.

For the better part of 70 years, it’s been the assumption that top students would go to a 4-year university, get a bachelor’s degree (at minimum), then continue on in an office environment, working their way up the ranks until they’re in the corner office on the highest floor. Only the students who can’t hack it end up in trade school, and blue collar work is seen as a dead end path.

In truth, blue collar work has a multitude of benefits, and should be a serious consideration for any high school student thinking about what to do with his life, or any man currently in a job he hates. The pay is good, the job security is strong, and trades work comes with numerous intangible advantages — from greater autonomy to the satisfaction of working with one’s hands and solving concrete problems.

Blue collar work is ultimately deserving of much greater respect than we currently offer it. Tradesmen made America what it is. Our buildings, our roads, our homes, our cars, our infrastructure of abundant energy and clean water – all of these things were built by the calloused and greasy hands of blue collar workers. Our culture of hard work and hustle and daring was forged by bootstrapping men atop iron beams hundreds of feet in the air. While it may seem these careers belong in a museum in our techno-entrepreneur world, that couldn’t be further from the truth. America still needs new skyscrapers, abundant energy, updated roads and highways, and water systems that will save us from droughts. These are projects that are undertaken by the tradesman, not the white collar office man.

What I’ve tried to impart throughout this series is the absolute necessity of both types of work in our world. We need those who work deftly with their hands, and those who work primarily in front of a computer screen. So if life in a cubicle doesn’t seem like the right path for you, forget the old stereotypes and myths that the only good jobs are those that require a bachelor’s degree. Our world truly needs those willing to get their hands a little dirty (and you’ll be well compensated to boot!).

Throughout the year, as part of this series on reviving blue collar work, I’ll be doing So You Want My Job interviews with tradesmen in various fields. Plumbers, truckers, welders, mechanics, and even an elevator technician. Stay tuned!

Read the Entire Series

4 Myths About the Skilled Trades

5 Benefits of Working in the Skilled Trades

How to Start a Career in the Trades