For the past few decades, there’s been an intense focus on getting more women in the workplace and helping them thrive and succeed. At the same time, however, a silent problem has emerged that could have serious repercussions on our economy and society: more and more men have been dropping out of the workforce.

My guest today is an economist with the American Enterprise Institute who has written a book highlighting what he calls an “invisible crisis.†His name is Nicholas Eberstadt and his book is Men Without Work. Today on the show, Nicholas delves into the research that shows that while unemployment is down, the number of men actually working or looking for work is lower than a generation ago. We then delve into some of the possible causes of the disappearance of men from the workforce, what these non-working men are doing while they’re not working, and how they’re supporting themselves without a job. Nicholas then discusses the possible economic and societal problems that this growing number of non-working men create, and what we can do on a micro and macro level to encourage men to be self-reliant and industrious.

Show Highlights

- Why the topic of men in the workplace is what Nick calls “an invisible crisis”

- The difference between employed, unemployed, and out of the labor force

- Where unemployment statistics come from, and their reporting history

- How many men of prime working wage aren’t working?

- Is this problem unique to America?

- What is going on in America that’s taking men out of the workforce?

- How convicted felons who are no longer in prison impact the workforce

- What are non-working men doing with their time?

- The economic and social ramifications of a disengaged population of men

- The education level of men not in the labor force

- How are these men supporting themselves? What does their living situation look like?

- Is this a solvable problem?

- Why Nick decided not to include many solution ideas in his book (and the few that he did)

- The role of faith and family in helping out these men who aren’t in the workforce

- Is there anything the individual listener can do?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Bureau of Labor Statistics “Not in Labor Force” charts

- American Time Use Surveys

- Millions of people are neither working nor learning

- Americans taking prescription pain relievers

- Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century

- Is College for Everyone?

- Reviving Blue Collar Work

- Podcast with Mike Rowe about the trades

- The Decline of Empathy

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Saxx Underwear. Everything you didn’t know you needed in a pair of underwear. Get 20% off your first purchase by visiting SaxxUnderwear.com/manliness.

Proper Cloth. Stop wearing shirts that don’t fit. Start looking your best with a custom fitted shirt. Go to propercloth.com/MANLINESS and enter gift code MANLINESS to save $20 on your first shirt.

Grasshopper. The entrepreneur’s phone system. Have a separate number that you can call and text from by going to grasshopper.com/manliness and get $20 off your first month.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For the past few decades, there’s been an intense focus on getting more women in the workplace and helping them thrive and succeed there. At the same time, however, a silent problem has emerged that could have serious repercussions on our economy and society. More and more men have been dropping out of the workforce completely.

My guest today is an economist who has written a book highlighting what he calls an invisible crisis. His name is Nicholas Eberstadt, and his book is Men Without Work. Today on the show, Nicholas delves into the research that shows that while unemployment is down, the number of men actually working or looking for work is lower than a generation ago. We then delve into some of the possible causes of the disappearance of men from the workforce, what these nonworking men are doing while they’re not working, and how they’re supporting themselves without a job. Nicholas then discusses the possible economic societal problems that this growing number of nonworking men create and what we can do on a micro and macro level to encourage men to be self-reliant and industrious.

After the show’s over, check out the show notes at aom.is/menwithoutwork where you can delve deeper into this topic, and now, Nicholas joins me via ClearCast.io.

Nicholas Eberstadt, welcome to the show.

Nicholas Eberstadt: Hey, thank you for inviting me.

Brett McKay: You’re an economist, and you wrote a book last year called Men Without Work, and it highlights research that shows that there are fewer and fewer working-age men who could work and aren’t working, and you say this is an invisible crisis. Why is this issue of men, labor force participation an unknown or invisible crisis?

Nicholas Eberstadt: That’s a really good question. I kind of wondered about that while I was doing my homework for this. Maybe it’s little bit less invisible since the 2016 presidential election, but we have to ask why a problem that was gathering for half a century was basically outside the radar screen of the decision makers in Washington, the new media, academia for the most part. I have some guesses, but I don’t know the answer to this.

Partly, I think it is what my friend and AEI colleague Charles Murray referring to as the bubble effect. This is something that has been occurring outside the bubble, and people inside the bubble haven’t paid as much attention to it as they should. Partly, it’s because the flight from work, this exodus from the labor force by working-age men didn’t turn out to cause riots or other sorts of public security problems, so it could be ignored little bit more easily that way.

It’s also perhaps true that working-age men are not a designated victim class for the academy and for the media. They’re supposed to be self-sufficient, they’re supposed to be supporting other people, they’re not obviously a vulnerable group, and so maybe a little bit less attention was paid to their plight than would have been wanted. For whatever reason though, this problem has hidden in plain sight for two generations as it has almost steadily worsened.

Brett McKay: We’ll talk about its origins. I think a lot of people think that this is a recent phenomenon, but we’ll talk about how it’s, no, this started, as you said, two generations ago, but let’s get to definitions because I think for the layman who hears unemployed, they think, “Oh, they’re just, these guys are just unemployed, and they can’t get a job,” but what you’re looking at, no, they’re not just unemployed. They’re also not even just, they’re not even looking for work.

Nicholas Eberstadt: Yeah, I’m glad you framed it that way. We’ve got three classifications. You can be employed. You may only be employed for an hour a week, but you’re getting paid work. That means you’re classified as employed. You can be unemployed. That means you don’t have any paid work but you’re looking for paid work. Then there’s a third category: You’re out of the labor force altogether. You’re neither working nor looking for work.

Nowadays, in America for every prime-age guy, let’s say prime age is defined by the Labor Statistics folks as 25-54 years of age. For every prime-age guy who is unemployed, there are another three who are neither working nor looking for work. They’re totally outside the unemployment statistics, and if you just look at the unemployment statistics, you’re missing three-quarters of the problem.

Brett McKay: How do economists figure out exactly how many men are there out there who are unemployed but neither looking for work because unemployed, yeah, statistics, you can go to, you can look at people going to the unemployment office looking for benefits, but that’s not going to happen with a man who’s not even looking for work.

Nicholas Eberstadt: Well, so we have a national jobs report, which was devised as a consequence of The Great Depression. When The Great Depression hit, we didn’t have any national apparatus for gathering labor statistics. We just had the decennial population census so we know what it looked like in 1930 and we noticed what it looked like in 1940, but we didn’t know exactly how bad it was in like 1932 or ’33, so starting in 1940, the US government pulled together a system for cracking labor trends. We were about to launch it in 1941, but instead, we did a little thing called World War II, and so it had to be postponed until after we won the war and things calmed down a little bit.

This was launched in 1947. It’s a monthly report conducted by the Census Bureau for the labor department. It tracks people all over the nation in a way that’s supposed to be random and representative in the civilian non-institutional population if you want to get really nerdy. As to their existence and then their employment status, it depends upon asking people questions and upon relative accurate responses to those questions, although there are some ways of checking on it, but that’s the bread and butter for our post-war employment statistics, unemployment statistics, and also for finding out about people who are neither working nor looking for work but are of prime working age.

Brett McKay: Roughly based on these statistics, how many men in the prime working age are not working today?

Nicholas Eberstadt: Round number, today, 7 million between the ages of 25 and 54.

Brett McKay: 7 million, man.

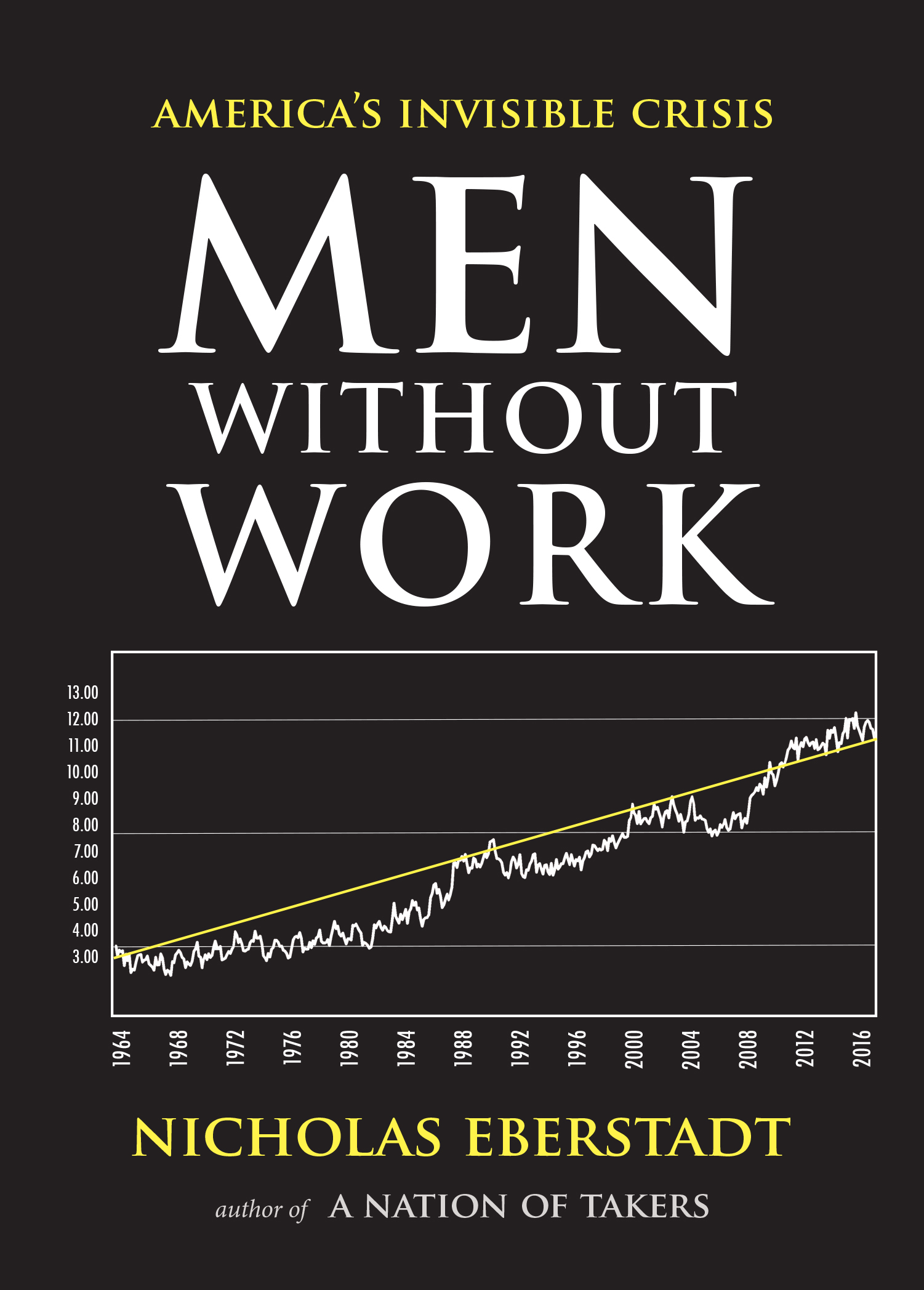

Nicholas Eberstadt: It’s an enormous army. This army of men who are neither working nor looking for work in prime-work ages has been growing three times as fast as the total population of prime-age men for fully half a century. If you do anything three times as fast as something for half a century, you change the world. At this point in time, more than a tenth of all civilian non-institutional prime-age men are out of the workforce altogether, neither working nor looking for work. That’s in addition to those who are formally unemployed.

Brett McKay: This isn’t a recent phenomenon. This, as you argue in the book, this began in the 1960s?

Nicholas Eberstadt: Yeah. From the first months of the jobs reports in the late 1940s until the mid 1960s, there was really no trend. The proportion of men not that work kind of bounced around without any sort of real direction to it. It was kind of seemingly stable over this long period.

Around the mid-1960s, there’s a breaking point, and since then, the proportion of guys who are neither working nor looking for work has grown exponentially. If you flip it around the other way, if you look at the percentage of guys who have paid work, you can see a real collapse. The percentage of guys with paid work in the United States has dropped from almost 96% in the mid-60s to about 85% today. It’s dropped by more than 10 percentage points.

In fact, if you look at the latest figures that came out last month for the percentage of prime-age guys with paid work, even an hour of paid work a week, it’s slightly worse than it was in 1940, in the 1940s census, which is to say at the end tail end of The Great Depression when the national unemployment rate was over 14%, so the scale of the problem we’re looking at today is kind of Great Depression scale.

Brett McKay: Wow. Is this a uniquely American problem, or are other Western industrialized countries seeing the same issue?

Nicholas Eberstadt: Well, all rich Western democracies have seen some decline in the percentage of prime-age guys in the workforce over the past, let’s say, two generations, but our decline is by far the worst. Ours is the steepest and the largest. We have to wonder why is that? I mean, there are a bunch of other rich countries around the world who’ve had economies that have been a lot more moribund than ours over the last 50 years. I mean, look at what’s happened in Japan over the last generation. It’s been pretty flat in the water, but Japan’s performance, it’s a lot better than ours.

You take a look at a place like France, which has got a famously rigid set of rules on the labor market. It’s got a great big expensive welfare state. Their labor force participation for guys is a bunch above ours. I mean, Greece is in extremis kind of perennially, but its performance is also more favorable than ours, so there’s something, how would you say. We’ve won a race that we don’t want to win, and we’re exceptional in a way that we shouldn’t want to be exceptional.

Brett McKay: Why is that? I mean, what is going on in America. Are there fewer well-paying jobs, is it a cultural thing? What do you suspect? I know there’s no definitive answers but what are your hunches?

Nicholas Eberstadt: Well, of course, like any other great big historical change, I don’t think we can have a one-factor theory of history. It’s probably a bunch of different things. In the USA, like other rich industrial democracies, we’ve had a big, you might call a structural economic change. We’ve had the decline of manufacturing. We’ve had more trade competition, China and the world trade organization, outsourcing, decline and demand for less skilled work, all of that’s a very big factor in this.

We’ve also clearly had some changes in the way that our social welfare state works, our social welfare state is, I’m constantly reminded when I go to other affluent societies, is a very stingy one compared to theirs, so it’s not the scale of generosity, perhaps, of our social welfare state, but maybe some of the perverse incentives. We have a sort of a disability archipelago, which plays a very important role in providing alternative income to men who are neither working nor looking for work in this prime age of life.

We also have something which is kind of invisible, and I think terribly sad and overlooked in our society, which is quite different from almost any other country on earth, and this is the enormous, invisible population of felons, of people who have been sentenced to a felony who are not behind bars. Uncle Sam does not collect information on this, I think, to our shame, but others who have attempted to estimate the size of this population suggest that as of the year 2010, there are over 19 million adults in America with a felony in the background.

Now, they’re, obviously, overwhelmingly, guys. If you do the arithmetic and look at flows and stocks, today, there are most likely over 20 million Americans not behind bars in society as a whole who have a felony in their background, overwhelmingly, guys. This means that today, whether or not we discuss it in general in public, something like one in eight adult guys not behind bars has a felony in his background, and probably a somewhat higher proportion for the men of prime working age. This is one thing that is very different in America from any other rich country, and I have to think that this is part of the tableau we’re looking at as well.

Brett McKay: Right, because on most job applications, they ask you if you have committed a felony, and that might be a reason people don’t hire them.

Nicholas Eberstadt: Well, that’s one of the reasons. I mean, it’s kind of ironic. There’s a movement in different places around the country called Ban the Box, which is supposed to mean that employers are not allowed to ask about that, and ironically, in the places where this initiative has succeeded, people are much more likely not to hire ex-cons because they presume that everybody’s an ex-con, so it has the opposite of its intended effect, but it’s certainly true that if you’ve committed a felony there are a whole bunch of things you can’t do. You can’t work in financial services. I mean, you could just think about all the different things you can’t do, but there are other aspects, which I don’t think we really understand enough.

I mean, in my book, using non-government data, I show that no matter what a guy’s age or his ethnicity or his educational level, he’s way more likely to be out of the workforce if he’s been to prison than if he’s just been arrested, and way more likely to be out of the workforce if he’s just been arrested than if he’s never had any trouble with the law.

Now, I can’t tell you why that is. I mean, one reason might be discrimination against felons. Another might be that people who go to prison lose their skills somehow while they’re in. Another hypothesis might be that employers just aren’t all that interested in the type of people who tend to get in trouble, or there may be something else, or there may be other things, or it may be some combination of these but as long as we have this glaring lack of information about this now enormous share of our adult male population, we don’t know. We can’t know.

Brett McKay: Right. Well, give us a snapshot. I mean, what does this disengaged male worker look like? I mean, what, average age, I guess the average is between 25 and 50, but where do they live, primarily, what do they do with all their spare time? If they’re not working, what are they doing?

Nicholas Eberstadt: Well, let’s start with that. We can tell about that aspect of life from information the government regularly collects in what are called Time Use Surveys. These are things which the labor department collects to get an idea of when people are working and what they’re doing, getting to work and stuff like that, but they also ask people who aren’t employed about this, adults who aren’t employed.

Of the 7 million neither working nor looking for work between the ages of 25 and 54, a little bit more than a tenth are adult students. They’re studying, they’re trying to gain skills, presumably to get back in the game and get a better job. Their time-use looks pretty much like employed men. The overwhelming majority, though, of guys in this “out of the labor force” pool are in what is called the NEET category, N-E-E-T, neither employed nor in education or training. For them, the picture is pretty grim. I mean, for one thing, and this is all self-reported, people in this group basically don’t seem to do civil society: not much volunteering, not much charitable work, not much worship. You might think they have nothing but time on their hands, but they do relatively little in the way of childcare or caring for other people in their household, family, and not that much in the way of household chores.

What they do, what they report doing is watching, and the surveys don’t ask whether it’s watching a TV or a handheld device or a laptop or whatever but it’s watching stuff about 2,100 hours a year, which is akin to a full-tie job. The same Time Use Surveys suggest that these guys are getting out less and less, that they’re not leaving the house, not traveling outside the house as much today as they used to in the past.

Now, some other work that was done since I published this book suggest that a very large proportion of these men not in the labor force are taking pain pills. Maybe something like almost half taking pain pills every day according to self-reported survey data. This tableau is not just of guys sitting at home playing World of Warcraft, it’s playing World of Warcraft while stoned. It’s a very grim picture.

Brett McKay: That is grim. I mean, what are, I mean, that, for the individual, it’s grim, but let’s talk about a societal ramification. What are some of the economic and social ramifications of having so many disengaged men from the workforce?

Nicholas Eberstadt: More or less exactly what you’d imagine, and none of it good. What does it mean? You have this enormous chunk of prime-age male manpower sidelined in this sort of way. Well, slower economic growth, bigger income gaps, bigger wealth gaps in society, more social welfare dependence, probably higher budget deficits, and thus, higher public debt, obviously, more pressure on fragile families, less social mobility, less healthy civil society. I mean, just go through the whole thing. There’s nothing good in that. It’s all bad. I mean, I wish I could figure out a good thing in it, but it’s a problem for the individuals, it’s a problem for their families, for their communities, and for our nation.

Brett McKay: Do they, I mean, I guess the individuals are having … They’re taking pain medication, which they probably might not even have physical pain. It might be a way to sooth the psychological pain, but I think when guys hear like, “Oh, you just get to watch TV and play video games all day,” and it sounds like the dream life, are there some men who are like that? They’re like, “Yeah, just, I have no desire to get back into work. Even though I could, this is great for me. I want to keep doing this.”

Nicholas Eberstadt: Well, if you look in particular at what has happened to the Anglos, the non-Hispanic whites, at working-age men. It’s true of working-age women too, I guess, but if you look at the men in particular, there’s been a noticeable increase in death rates for lower-skilled prime-age Anglo men over the past two decades, let’s say. A lot of these are from what the Princeton economist, Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Angus won the Nobel Prize in economics a couple of years ago, a lot of these deaths are from what they call deaths of despair, from cirrhosis of the liver and from drug overdoses and from suicide. That aspect of it doesn’t look like such a happy picture. Now, this isn’t only men not in the workforce. I hasten to say that they weren’t focusing just on that group, but that’s part of it, and the consumption of pain medication looks to be a lot higher for those who are out of the labor force altogether than for unemployed or employed guys.

Brett McKay: Going back to what this demographic looks like, are education level, is it just primarily just high school grads? Are there college grads, or is it primarily a lower education demographic?

Nicholas Eberstadt: I’m glad you asked that. If you have, let’s say, 7 million people in the group, you’re going to have some of everybody, most likely, but as you indicate, some groups are over represented, and some are underrepresented. To start with the ethnic thing, African Americans are decidedly overrepresented in this group, but among what’s called persons of color, both Asian and Latinos are underrepresented. They’re more likely to be in the labor force than the national average.

With education, it’s just like you said. High school dropout’s way more likely to be in this group than the national average. College grads and people with graduate degrees, way less likely. Turns out that marital status is a big predictor. No matter what your educational background or ethnicity, if you’re married, you’re less likely to be in this group. If you’ve never been married, you’re way more likely to be in this group, no matter if you have kids or not. Having a kid at home, by the way. All of the things being equal means you’re less likely to be out of the labor force, more likely to be in the game, in the labor force looking for work or getting work.

Then there’s finally this category that the Census Bureau awkwardly calls nativity, and it doesn’t mean Christmas scenes. It means whether you were born in the USA or not. Guys who are born in America are more likely to be out of the workforce altogether than guys who are born abroad, and it doesn’t matter, again, about your ethnicity. Asian, Anglo, African American, Latino, immigrants of all flavors are more likely to be in the workforce than their native-born counterparts.

That’s kind of the broader picture of how different social categories look in this respect.

Brett McKay: How are these men supporting themselves, and what’s their living standard like? You mentioned disability payments is one source.

Nicholas Eberstadt: From what we can divine from government information on spending patterns, which I think are the important numbers in trying to understand consumption and standards of living. The men who are out of the workforce altogether are not in the bottom fifth of our income distribution. People who are in the bottom fifth of our income distribution and our spending patterns are single mothers. They’re the ones who are in the most disadvantaged positions. These men without work, without workforce participation are in the quintile above that.

Ironically, they’re kind of in the group that used to be the status for people who are called working class, except these are guys who are neither working nor looking for work. They clearly have lower standards of living than men who are at work. They are drawing their sustenance off of their families, other family members, off of their girlfriends, and off of their uncle, and that uncle would be Uncle Sam.

According to one government survey done by the Census Bureau, almost three in five of the guys who are neither working nor looking for work in this critical group, the 25 to 54s, almost three in five receive benefits from at least one government disability program. If you qualify for benefits from disability programs, by convention, then are eligible for other benefits as well: low-income, health care, Medicaid, SNAP, which we used to call food stamps, and other things like that.

It is clear that men who are out of the workforce don’t live like princes, but on the other hand, they are not at the bottom of US society, either.

Brett McKay: What do you think we can do about this? I know you’re primarily describing the problem and don’t get too much in the prescriptions, but what could we do to solve this issue, or is it solvable?

Nicholas Eberstadt: Well, it’s a big, long-term historical trend, so I tend to think that big, long-term historical trends take a while to turn around. Doesn’t mean they can’t be turned around. Of course, we have to try to turn them around. I was very light on recommendations in this book, partly because I didn’t want to bigfoot this. It seemed to me it was much more important to get people talking about the problem and offering discussions from all around the public square than to have Mick come in with his, I don’t know, Ten-Point Program or whatever to show us the tablets from the mountain. For what it is worth, I would talk about things that government can do and things that government can’t do, and then a couple of things that maybe government should be looking at among things that it possibly might be able to do.

This problem clearly corresponds with the breakdown of the family in post-war America. That’s something I don’t think the government can fix, and I think I’d be kind of scared if the government set up a bureau for fixing the family in America because the unintended consequences of that would be unimaginable. It may be worse than anything positive they tried to do. The family is a huge aspect in here and probably outside of Washington’s purview. By the same token, religion and faith has some important role here, and I’m not sure we should want Uncle Sam to be monkeying around with that, either. That’s a civil society matter.

Among things that the government might be able to do, however, I would point to three or four in particular. One is skills. College is not for everybody, obviously, but nobody should graduate without having a skill. One of the awful things about education in America today is a lot of people graduate from high school without a marketable skill. We need to fix that broken aspect of our educational system and maybe destigmatize vocational training a little bit. That’s one thing that could be done, not necessarily in Washington, maybe in localities, but it’s something in general that should be examined.

Second thing: We’ve seen small businesses in America increasingly struggling. This is a trend that goes back decades. It’s happened under republican presidents, under democratic administrations, under red congresses, blue congresses. We’ve had a long-term trend of declining business startups. It’s not entirely clear why this is. I mean, I suspect it is related in part to the increasing difficulties that small businesses face in attracting finance and the growing hacks burden that they face and the growing regulatory burden, not just in Washington, in states and localities as well. If we have a healthier small-business environment, we’re going to have a much better job-creating engine than we enjoy right now. That’s the second thing I think worth looking at.

Third has to do has to do with our disability insurance programs. They were established for a very good purpose, which is to provide social insurance for people who can’t work. The programs, as a whole, have mutated away from their intended purpose, and there are a lot of people now who rely on disability programs as an alternative to employment. It’s hardly a princely life. It’s a penurious income, but it is an alternative to working life. We had a welfare reform 20 years ago that worked pretty well in transforming aid for families with dependent children into a temporary assistance for needy families. I think we should wholesale reform our national programs for disability benefits on a work-first principle. I realize that’s easier said than done, but that would be the objective.

Then finally, we’ve got this invisible population of 20 million people who are ex-felons, who are living in the shadows of society. I mean, that’s kind of appalling. We’re a government that set up the census in 1790 because our founders thought that information was important for public policy. That was more than two centuries ago. Can’t we really have some information about how people in this enormous group live, what their health is like, what their employment is like, what their incomes are like, what their government program dependence is like? We can’t have evidence-based policies for bringing people out of this pool and into the workforce unless we have the evidence. Those would be a couple of the direction that I think might be worth examining. Let’s put it that way.

Brett McKay: What do you think, for people who are listening to this podcast, sure, they could go and write a letter to their congressmen about these issues and vote for someone who’s got this on their platform, but what can individuals in civil society do-

Nicholas Eberstadt: Well-

Brett McKay: … to help with that program?

Nicholas Eberstadt: Well, I mean, of course, there’s, to begin with, what we might call the empathy barrier. In a time of increasingly gated communities and a decreasing contact between social strata, you might start by wanting to get out a little bit and seeing how the other half is living and what the real life circumstances of some of your fellow American citizens are like and then maybe you’d have a little bit more perspective on some of the problems which we are facing today because what’s happened in the US over the last decade or so is that the escalator has broken for a large fraction of our fellow citizens.

I guess I’d say the first thing we outta do is get out a little bit and recognize the reality. The information revolution has been wonderful in numerable ways, but it’s also balkanized us, and in a way, it’s kind of separated us from our fellow citizens because we all find self-validated, self-confirming sources of news, and in some ways, may retreat from the public square a bit. I think it would be really valuable for more contact between Americans. I realize that’s extraordinarily vague to say, but I think that might be a very positive starting point for self-informing approaches towards addressing really long-term problems in our country.

Brett McKay: Well, Nicholas Eberstadt, this has been a great conversation. Thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

My guest today was Nicholas Eberstadt. He’s the author of the book Men Without Work. It’s available on amazon.com. Also, check out our show notes at aom.is/menwithoutwork where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoyed the podcast and gotten something out of it, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us review on iTunes or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. If you’ve already done that, thank you. Please share the show with a few of your friends. Word of mouth is how this show expands its audience. The more, the merrier. As always, thank you for your continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.