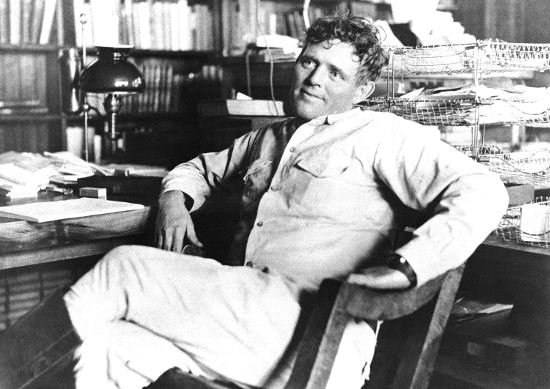

Imagine, if you will, a day in the life of Jack London — fascinating adventurer and author of hundreds of short stories and more than 50 books, including classics like Call of the Wild and White Fang.

Come into his room on a typical morning, and see him propped up against a pile of pillows in bed. A mound of cigarettes sits on a plate on his nightstand. Notes hang from a clothesline strung across a corner of the room. The author is writing his latest story in longhand on a pad resting on his lap.

What’s London’s state of mind as he brings to life another of his muscular tales of the Klondike? Is he glowing with the vigor and inspiration that comes from laboring at the very vocation he was born to do? Do the muses descend upon his keen mind and practically compel his hand across the paper? Is he animated by passion, lost in the reverie of creative work?

Decidedly not.

Rather, London describes his work this way: “I go each day to my daily task as a slave would go to his task. I detest writing.” And on another occasion: “I am nothing more than a fairly good artisan. I hate my profession. I detest the profession I have chosen. I hate it, I tell you, I hate it!”

If London disliked writing so much, why did he pursue this career? Simply because it was “the best way [he] had ever found to make a very good living.” London had a knack for writing, and it paid well, allowing him to support his family and expand his ranch, so he struggled through it nearly every single day for the last decade and a half of his life.

London may not have liked his profession, but he pursued it as an absolute professional.

Are You a Professional or an Amateur?

“Inspiration is for amateurs; the rest of us just show up and get to work.†–Chuck Close

We’re used to thinking of the word “professional†in terms of someone meeting the skill-level and standards of a certain career, or as a member of a particular class of well-educated, well-paid workers.

But the origin of the word traces to the Latin professionem — meaning “to declare openly.†In the Middle Ages, this became the Old French profession, which was used to describe the vows taken upon entering a religious order, and then became a term for any kind of solemn declaration.

I would like to suggest reviving this perspective on professionalism — viewing it as an attitude, a mindset, an ironclad commitment towards the labors before you. Perhaps you don’t detest your job as much as London did, but even in a job one loves, there are invariably tasks that are dull, difficult, and irritating, and must be muscled through with willpower. While “amateurs†wait until they feel like doing such work, “professionals†have vowed to get a job done, no matter their mood. This vow might be based on a commitment to creating something of beauty and importance in the world, or simply providing for one’s family.

In some ways, adopting a professional mindset is actually easier in jobs that are straightforward and tedious all the way through than ones which include a mix of the imaginative and the boring; with the former, it can be easier to detach yourself from the work and think, “I’ve got to do x, y, and z and then I get to clock out.â€

But with work that involves a degree of autonomy and creativity, there is a cultural expectation that passion and inspiration must be prerequisites to the work. Artists, craftsmen, and entrepreneurs who labor in the absence of this motivation can be seen as inauthentic hacks.

But despite the popular picture of passion-filled creative work often presented in movies and books, in reality it’s usually only go-nowhere amateurs who wait for inspiration to tackle a task. Professionals (in the sense of vow-takers), on the other hand, take action, knowing that inspiration will follow. Since action breeds feelings more effectively than feelings lead to action, professionals ultimately end up with more, and more consistent, inspiration than amateurs, and make more progress on their goals. As London exhorts: “Don’t loaf and invite inspiration; light out after it with a club, and if you didn’t get it you will nonetheless get something that looks remarkably like it.â€

Of course, the call to adopt the mindset of a professional sets up something of a catch-22: you want to work even when you don’t feel like working, but how do you start working if you don’t feel like it? The solution to this dilemma lies in adopting a thoroughly professional daily routine.

Daily Routines: The Powerful Lynchpin of Creative Professionalism

“My experience has been that most really serious creative people I know have very, very routine and not particularly glamorous work habits.†–John C. Adams (composer)

When author Mason Currey set out to discover how the world’s foremost creative types managed their work and day-to-day lives, what he found was an ample diversity in their habits. Some rose early, while others slept in (though it’s interesting to note that amongst the 161 lives Currey surveyed, the early birds outnumbered the night owls more than 2:1!). Some stood while working, some sat at a desk, and others lounged in bed. Many liked absolute solitude and silence, while a few didn’t mind interruptions. Some authors dictated; some typed; some wrote in longhand.

Yet despite the ways in which the routines of these writers, thinkers, and artists differed, there was one near universal among them: they made and stuck to a daily routine! While a few did their creative work before or after 9-5 jobs, most could have spent their days however they liked — making each one different than the last. Yet instead, the vast majority of the most creative folks in history labored not in spontaneous, passion-filled bouts, but rather much like London did: by keeping to daily, workaday, unalterable routines, whether they felt like it or not. In the absence of any externally imposed schedule or structure, they imposed their own, and often kept it for years, even decades. Charles Dickens’ son, for example, remembered his father’s writing habits as more methodical and orderly than that of a city clerk: “no humdrum, monotonous, conventional task could ever have been discharged with more punctuality or with more business-like regularity, than he gave to the work of his imagination and fancy.â€

Why do such creative people, who enjoy far more freedom in how to structure their lives than most of us, still bind themselves to a workaday schedule?

In order to effectively and consistently unleash their genius.

A routine acts as a hedge against one’s fluctuating feelings; as Currey explains, it serves as the fulcrum that helps the professional fulfill his vow to get the job done:

“In the right hands, it can be a finely calibrated mechanism for taking advantage of a range of limited resources: time (the most limited resource of all) as well as willpower, self-discipline, optimism. A solid routine fosters a well-worn groove for one’s mental energies and helps stave off the tyranny of moods.â€

Routines make the daily choice to get to work more automatic; you don’t have to continually gauge your feelings and decide again and again whether or not you’re going to get going on your tasks. When you hit walls, or have to accomplish the less glamorous aspects of your work, a routine keeps you moving.

Just as importantly, routines set up the conditions by which a man can discover, rather than wait for, inspiration. In his memoir, On Writing, Stephen King compares the way in which a bedtime routine can prepare someone for a good night’s rest, to the way in which a solid daily routine can prime the pump for “waking dreams†and “creative sleepâ€:

“Like your bedroom, your writing room should be private, a place where you go to dream. Your schedule — in at about the same time every day, out when your thousand words are on paper or disk — exists in order to habituate yourself, to make yourself ready to dream just as you make yourself ready to sleep by going to bed at roughly the same time each night and following the same ritual as you go. In both writing and sleeping, we learn to be physically still at the same time we are encouraging our minds to unlock from the humdrum rational thinking of our daytime lives. And as your mind and body grow accustomed to a certain amount of sleep each night — six hours, seven, maybe the recommended eight — so can you train your waking mind to sleep creatively and work out the vividly imagined waking dreams which are successful works of fiction.â€

In other words, creativity is a habit like any other — one you can cultivate by “clocking†in and out of a consistent, professional, daily routine.

The 4 Keys to a Professional Daily Routine

“Routine, in an intelligent man, is a sign of ambition…A modern stoic knows that the surest way to discipline passion is to discipline time: decide what you want or ought to do during the day, then always do it at exactly the same moment every day, and passion will give you no trouble.†–W. H. Auden

Even though the work habits of the artists Currey covers in Daily Rituals were diverse, most shared several common traits that together add up to a thoroughly professional, productive routine:

1. Do your most important work first. Nearly all the artists Currey surveyed would jump right into their most important tasks at the start of their routine. This allowed them to apply their freshness to their most vital and demanding work. As Johann Wolfgang von Goethe observed, a man labors best when “feeling revived and strengthened by sleep and not yet harassed by the absurd trivialities of everyday life.†It’s the “big rocks†principle: it’s much easier to fit in all of your lesser to-dos after your foundational work has been done, than it is to structure your priorities the other way around.

2. Strive for continuous consistency. You might think that strict daily routines were only adopted by writers and artists who were already a bit square and pedestrian in their habits. But even those inclined to partying, irregular sleep, and indulging in various vices still stuck to their daily routine — hangovers be damned. Ernest Hemingway, for example, would wake up at the first light of day and start writing, even if he had been up late drinking the night before.

The problem with letting circumstances dictate whether or not you’ll do your routine, is that there are always excuses to be found and reasons you deserve a break that day. Once you start taking breaks, it gets harder and harder to get back into the swing of things. As author John Updike mused: “I’ve never believed that one should wait until one is inspired because I think that the pleasures of not writing are so great that if you ever start indulging them you will never write again. So, I try to be a regular sort of fellow — much like a dentist drilling his teeth every morning.â€

It seems like it’s an article of faith that everyone must regularly take complete breaks from their work in order to fully refresh their minds and spirit. But in my own life I have actually found such total breaks to be counterproductive. I’ll be so tired of working that I can’t wait to take an entire week off from all things AoM; but then when the vacation is over, getting back into the groove proves quite difficult. After noticing that nearly every great man I studied, from Jack London to Winston Churchill, kept on writing, even while on holiday, I now do a little work-related writing and reading each day while I’m on vacation. When the break is over, I’m refreshed but also ready to hit the ground running. I concur with the composer John C. Adams, who said: “I find basically that if I do things regularly, I don’t have writer’s block or come into terrible crises.â€

Continuous consistency keeps you ever in fighting shape; or as another composer, George Gershwin, put it: “Like the pugilist, the songwriter must always keep in training.â€

3. Keep yourself accountable with clear, quantifiable goals. Simply sitting at a desk for an allotted number of hours does not an effective routine make. Even with creative pursuits, one should have a tangible goal for what will constitute a successful, productive use of time. Many writers, for example, set themselves a certain word count they must reach before knocking off for the day. King aims for a quota of 2,000 words a day, and keeps at it from 8:00 or 8:30 in the morning until that goal is reached — whether that’s 11:30 or into the afternoon. Hemingway would track his daily output on a chart, “so as not to kid myself.†London wrote 1,000 words every day whether he was at home or seasick at the bottom of a boat in the South Pacific; “Set yourself a ‘stint,’ and see that you do that ‘stint’ every day,†he recommended.

By setting small, reasonable, but consistent daily goals, one’s progress will slowly add up, and accumulate into remarkable results. Many famous writers, even those with 9-5 office jobs, found that by simply penning even just a few good pages a day, they could write a new book or novel every year.

4. Be in it for the long haul. What’s so remarkable about many of the eminent folks profiled in Daily Rituals, is that they weren’t just consistent about keeping with their routine every day for weeks, months, or even years, but in fact often kept at it for decades. For instance, Charles Schultz, the creator of Peanuts, worked alone seven hours a day, 5 days a week for almost 50 years. The reward of his professional working habits? Nearly 18,000 original comic strips and a legacy that continues to this day.

The overall effect of keeping a daily routine is that it enforces a certain regularity on the otherwise flighty currents of inspiration. You don’t wait for it to show up; you show up to it. Or as William Faulkner put it: “I write when the spirit moves me, and the spirit moves me every day.â€

Conclusion: Becoming a Creative Professional

When it comes to your life’s work, you can approach it either as an amateur or as a professional. You can decide to get to work only when you feel like it, or you can tackle your goals day in and day out, regardless of your mood. You can govern your feelings by establishing an invariable daily routine, or you can let your feelings govern you.

Many who wish to pursue more creative careers dream of throwing off the rigid schedule of the office worker for what they envision as a life of freedom and imaginative autonomy. Yet ironically, the ones who ultimately find success as entrepreneurs or artists of any kind, are typically those who pursue their craft with the same kind of structured, business-like routine! This is as true for the creative who is already making a full-time career of his art, as it is for those who wish to quit their 9-5 and transition to doing so; if you cannot yet work on your craft during a daily routine, you must moonlight with a structured, professional morning and/or evening routine that will move you towards your goal.

As part of that morning routine, consider reciting the little poem Jack London included as an epigraph to one of his short stories:

“Now I wake me up to work;

I pray the Lord I may not shirk.

If I should die before the night,

I pray the Lord my work’s all right.

Amen.â€