This article series is now available as a professionally formatted, distraction-free book to read offline at your leisure. Available as an ebook or a paperback.

A history of depression? Doesn’t depression just exist, like cancer? You can’t really write a history of cancer; perhaps how it’s been treated or diagnosed, but you can’t write a history of a disease in and of itself. It just is, right?

In the West, we commonly think of depression as just another biological illness like any physical malady (and how we got to this perspective is what we’ll explore today!). The comparison is tempting, as it diminishes the stigma around mental illness; you wouldn’t feel bad about treating a tumor on your spleen, so you shouldn’t feel bad about getting help for the invisible tumor on your brain, either.

And yet, as much as we’d like it to be, mental illness in general, and depression in particular, is not quite that simple. It’s a mix of the genetic and the environmental, the physical and the mental, the biological and the psychological. It’s also both individual and cultural.

This is to say that how we experience depression, and how we make sense of what’s happening to us, arises not only from our inner feelings, but what our culture says those feelings should mean. And that prism of interpretation has varied widely through time and place, and continues to diverge today. It’s important to know how and why this is.

Why You Should Understand the History of Depression

I’ll be honest at the outset in admitting that this article, while quite interesting (I think!), is a little dry and long. You may be tempted to skip it, and wait for our subsequent articles on depression’s causes and treatments, but I hope you decide to wade into today’s piece anyway.

Learning about the cultural history of depression in the West put my own bouts with it into a new perspective. For starters, it’s somewhat comforting to know that depression is something humans have dealt with for thousands of years. A common cognitive bias that pops up in individuals in the throes of deep depression is the feeling that their situation is unique and no one knows what they’re experiencing. But when you read accounts of Abraham Lincoln’s severe melancholy or Samuel Johnson’s diary entries agonizing over his despondent moods, the illusion of your depression’s uniqueness fades away.

What’s more, the history of depression provides a much more nuanced view of this mental and emotional state that us moderns call a disease. For much of Western history, depression was a Janus-faced condition that could be both a curse and a blessing.

Finally, studying the history of depression illuminates competing schools of thought about its causes and cures that have existed since Ancient Greece and continue to exist today. Rather than a steady march of progress, our understanding of depression has moved more like a pendulum, with different approaches and philosophies waxing and waning over the centuries.

I hope by the end of this crash course through the history of melancholy, you’ll gain a new perspective on depression. It will also lay the groundwork for our further exploration on how to leash the black dog in our own lives.

Let’s get started.

Ancient Greece and Rome

Some of the first accounts of what we today call depression, and what was then called melancholia, come from Ancient Greece. One such portrayal can be found on a vase from 400 BC that depicts a downtrodden and gloomy Orestes taking part in a purification ceremony to get rid of the Furies — injustice-avenging spirits — that hounded him after killing his mother. In Orestes, Euripides depicts the tragedy’s protagonist as exhibiting many of the telltale symptoms of depression: loss of appetite, excess sleeping, lack of motivation to even bathe, constant weeping, chronic exhaustion, and a sense of helplessness.

We can find further descriptions of melancholic individuals in other popular Greek works as well. For example, Jason the Argonaut was a great Homeric hero who you’d expect to demonstrate nothing but action and resolve in the face of adversity. Yet when he shipwrecks on the coast of Libya, his mighty mantle falls away and he becomes absolutely helpless and sullen.

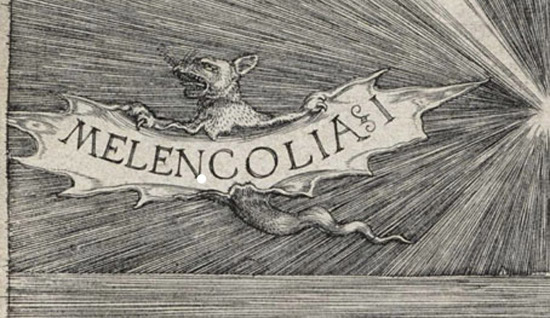

In the Greeks’ more scientific texts, melancholia emerges as an illness in the 4th century writings of Hippocrates. For the ancient physician, melancholia constituted a depressive temperament brought on by an imbalance of the bodily “humors” or fluids. Hippocrates believed that the human body was composed of four substances: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. Any sickness or disease in the body was the result of an excess amount of one of these fluids, and the doctor’s job was to bring the humors back into balance by purging, bloodletting, and/or medications.

Hippocrates and other ancient Greek physicians posited that depressive melancholy was the result of an excess of cold black bile in the body (hot black bile caused mania or madness). The greater the overabundance of cold black bile, the more severe the depressive state. To cure a patient of his illness, his black bile simply had to be reduced.

While it’s easy to laugh at this theory, Hippocrates did get something right: he concluded that mental illnesses, like severe melancholia, had something to do with the brain: “It is the brain which makes us mad or delirious, inspires us with dread and fear, whether by night or by day, brings sleeplessness, inopportune mistakes, aimless anxieties, absentmindedness, and acts that are contrary to habit. These things that we suffer all come from the brain when it is not healthy, but becomes abnormally hot, cold, moist, or dry.”

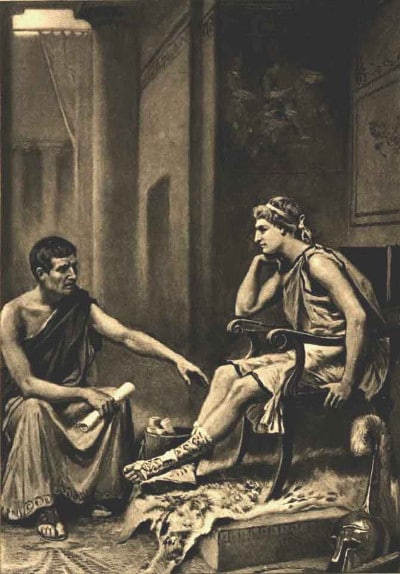

The ancient Greeks believed that depression was caused by an overabundance of cold black bile (one of the fluids that made up the human body), and that it had both drawbacks and advantages. Aristotle pondered: “Why is it that all men who have become outstanding in philosophy, statesmanship, poetry, and the arts are melancholic?”

Implicit in this humor-driven approach to melancholia is that one could have varying degrees of it. Someone could have just a slight excess of black bile and experience mild melancholia, or a severe pile-up that bred serious mental illness. Greek thinkers believed that the mild version was linked to genius and creativity. In Problematic 30, a work attributed to Aristotle, the philosopher posits that heroes like Lysander, Ajax, Plato, and Socrates had a mild melancholic temperament, and that it was their blue moods that allowed them to do great deeds and think lofty thoughts.

Ancient Roman doctors continued the study and treatment of melancholia. Galen, a second century Roman doctor, would have a particularly lasting influence on its treatment. Like Hippocrates, Galen believed that melancholia and other related mental illnesses were the result of a humoral imbalance, but he also theorized that some individuals are simply born with a temperament that makes them prone to the condition and that medicine could do very little for these individuals.

Competing against the humor-based, biological approach to depression were more spiritual and philosophical theories. Greek temple priests believed depression or mania was a spiritual curse from the gods; only by petitioning the deities for relief could one be cured. Plato, on the other hand, unsurprisingly had a more philosophical take on the matter. For him, depression was a sickness of the soul that could be remedied by bringing into balance the three parts of a man’s psyche: reason, desire, and thumos.

The Roman Stoics also took a philosophical approach to melancholia and argued that mental and emotional disturbances were caused by having a faulty perception of one’s experiences and situation. These philosophers believed that how you mentally framed disastrous or stressful events could heighten or quell your anxiety (and consequently your melancholia). Thus, they argued that simply changing your cognitive perception of your circumstances could alleviate your mental anguish.

Treatments of melancholia proliferated in Greece for the next 400 years, and many of them were used up through the Renaissance. Potions, prayer, philosophical reflection, walking, sleeping in hammocks, and drinking human breast milk were all remedies doctors prescribed for centuries to patients with depressive moods.

Medieval Times

The Middle Ages carried on the classical idea of depression being rooted in one’s disfavor with the gods, but this time the gods were those of Christianity, rather than the Greek pantheon. For clerics in Medieval Europe, melancholy was a sign that one was living sinfully and in need of repentance. In fact, severe melancholy was sometimes seen as a sign of demonic possession. John Cassian, a monk known for his mystical writings, called melancholy the “noonday demon,” in reference to Psalm 91. He recommended that melancholics withdraw from family and friends and perform hard manual labor in solitude as punishment for their sins.

In the Middle Ages, melancholy was associated with sloth, which was considered a sin.

Not only was melancholy seen as a sign of sinfulness, being in a depressed state was considered sinful in and of itself; the Latin word for the deadly sin of sloth, acedia, was broadly defined and included everything from laziness to melancholy. In fact, many of the clerics who wrote about individuals beset with acedia described them as being in the throws of depression. For example, Cassian describes a fellow “slothful” monk this way:

“He looks about anxiously this way and that, and sighs that none of the brethren come to see him, and often goes in and out of his cell, and frequently gazes up at the sun, as if it was too slow in setting, and so a kind of unreasonable confusion of mind takes possession of him like some foul darkness.”

The Canterbury Tales, written in the 14th century, similarly describes the slothful person as one who is filled with despair, loss of hope, and “outrageous sorrow.” This excessive low mood is followed by sluggishness and general apathy towards life, which in turn prevents the slothful person from performing good works. If not repented of, sloth becomes a sin against the Holy Ghost. Andrew Solomon, author of The Noonday Demon, suggests that this connection between melancholy and the sin of sloth may have given rise to much of the stigma that surrounds depression today.

Renaissance

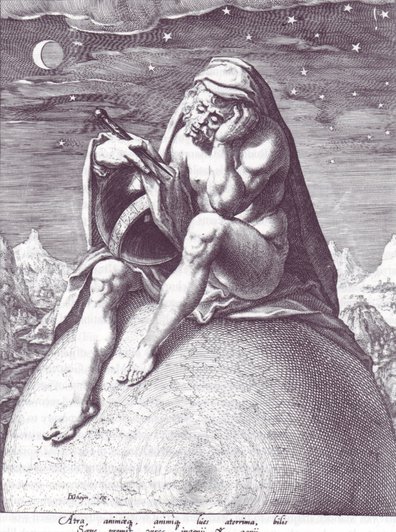

Some Renaissance thinkers believed melancholy was caused by contemplating the gap between humans’ divine potential and how far mortals could actually reach.

Along with looking back to ancient Greece to inform their art and philosophy, Renaissance thinkers did so to inform their view of melancholy as well. Instead of seeing it as a sign of sin, Renaissance writers and philosophers viewed depressive moods through the Aristotelian lens — as a possible catalyst of genius and greatness. Italian Renaissance philosopher Marsilio Ficino posited that the melancholics were such because they strived to understand the mystery and glory of God, but realized that they’d never be able to obtain it here on Earth; the gap between their lofty potential and their leaden feet left them in despair. Wrote Ficino: “As long as we are representatives of God on earth, we are continually troubled by nostalgia for the celestial fatherland.” For Renaissance Europeans, melancholy became a badge of honor that signified depth, soulfulness, and intellectual complexity.

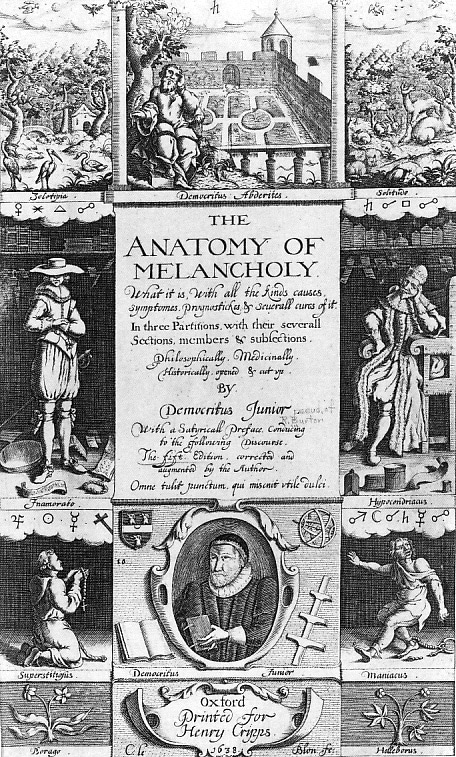

With this new (again) view of melancholy as the origin of genius, being depressed became somewhat fashionable in Renaissance Europe. Aristocrats and intellectuals took great pride in describing themselves with a touch of melancholic temperament and some devoted essays and whole books to the Janus-faced state of mind. For example, 15th century English scholar and melancholic Robert Burton’s 1,000+ page tome, The Anatomy of Melancholy, takes a look at the history, causes, and possible treatments of the condition. While Burton did provide antidotes for melancholy, he also emphasized the creative blessings that come with it.

This idea of fashionable melancholy manifested itself in popular culture as well. Plays would often feature sullen, downcast, and moody characters as individuals who had great insight into the human condition, the most famous of whom was perhaps Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Enlightenment

Alongside the advances of science and technology birthed during the Enlightenment era came changing ideas about melancholy. The rise of steam-powered machines in the 18th century inspired mechanistic analogies as to how the human body and mind worked; doctors of this period saw melancholy as a malfunction of the human machine. Theories were advanced that the cause could be found in faulty hydraulics (blood flow) or a failure in the elasticity of the body’s fibers or by “untuned” nerves. The idea that this disorder could be passed on from parent to child also came into vogue.

18th century English physician George Cheyne forwarded the theory that melancholy was caused by the increasing comforts and luxuries made possible by industrialization. To counteract the sickening effects of this rising decadence, Cheyne prescribed a spartan vegetarian diet (though he himself had a hard time abiding by it; the man loved to eat meat). Other thinkers and scientists agreed with Cheyne’s theory, and it found particularly strong purchase among the aristocratic class, for whom luxury was both a source of enjoyment and some discomfort. Edmund Burke stated that “melancholy, dejection, despair, and often self-murder, is the consequence of the gloomy view we take of things in this relaxed state of body. The best remedy for all these evils is exercise or labour.” Samuel Johnson, a melancholic himself, believed that rugged, rural living produced hearty and emotionally robust people, while city life sapped their resilience and made them vulnerable to depression.

Enlightenment philosophers and scientists elevated reason and spurned melancholy as a state arising from irrational thinking.

The other important development in the West’s view of melancholy to come out of the Enlightenment can be traced to the period’s emphasis on reason. Enlightenment thinkers prized the rational, and eschewed the melancholic mindset as anything but; somewhat like the Stoics, they saw the state as resulting from wrong thinking. Depression was not, as some Renaissance philosophers had seen it, a source of creativity, but only an illogical madness.

Romanticism

Just as it seemed a view of melancholy as wholly bad had thoroughly taken hold of Western culture, the Romantics turned the tide once again in the first half of the 19th century, reviving the idea that dark moods were the soil for creative genius and perceptive wisdom.

In what Emerson dubbed “The Age of Introversion,” gloomy temperament was seen as just one inborn personality among several, and that each had its advantages and drawbacks. In Lincoln’s Melancholy, Joshua Wolf Shenk notes that the melancholic disposition was “characterized by not only gloominess, asceticism, and misanthropy, but also deep reflection, perseverance, and great energy of action…To be grave and sensitive—to feel acutely the agony and sweat of the human spirit was admired—even glorified.” Lincoln’s own severe, lifelong melancholy (at age 32 he declared himself “the most miserable man living”) spurred him into public service, and drew citizens to him “as a person,” Shenk writes, with “access to the deep channels of the soul—the waters of sadness, the bedrock of constancy, the gold of mirth.” He was a man of sorrows who understood the travails of the everyday man.

Embracing and making the most of one’s melancholic disposition, rather than combatively fighting against it, was thus part of living authentically. Properly harnessed, Romantics felt it could lead to heroic action, and also of course to artistic output. Poets like John Keats and Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote odes to melancholy and dejection. Lord Byron called his dark moods “a fearful gift,” and philosophers like Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard likewise took comfort, and even delight, in their despair and anxiety. Wrote the latter: “In my great melancholy, I loved life, for I loved my melancholy.”

Romantics saw melancholy as a desirable state that inspired creativity and reflection. They sought out dreary literature, art, and landscapes to induce a gloomy mood within themselves.

Romantics celebrated emotion and intuition, and felt both could be found not only in joy, but in plumbing the depths and dark corners of the soul. Purposefully inducing a gloomy mood by reading sad poetry or wandering in a bleak and dreary place was felt to be a beneficial exercise for discovering self-knowledge.

While melancholy-as-insight once again experienced a revival, it was short lived. Developments in psychology and biology in the mid and late 19th century would lay the foundation for our modern conception of depression as a mental illness that impeded, rather than facilitated, being one’s true self.

Victorian Era: The Rise of Neurasthenia

Some Victorians thought low moods grew out of “neurasthenia” — an over-taxation of the nervous system brought on by the increasing pace of modern life.

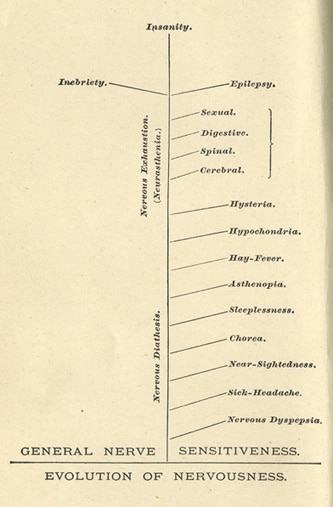

By the middle of the 19th century, psychology had become an established field of study, separate from biological medicine. Emergent shrinks forwarded the theory that melancholy was caused by an over-taxed nervous system. Many people were reporting feeling restless, lethargic, and depressed, and American neurologist George Miller Beard attributed these symptoms to the increasing pace of industrialization and the rise of new technology. He coined the term “neurasthenia” to describe this seemingly new condition that had arisen from the “nervous excitement” of modern life.

To avoid succumbing to neurasthenia, mid and late 19th century Americans and Europeans were advised to manage their “nerve force” lest it be over-taxed, and followed by a collapse into severe melancholy. Sufferers were told to avoid alcohol and meat consumption, late hours, and bad company. Walks and good conversation were also deemed beneficial in keeping one’s psyche in fine fiddle.

Men, particularly those working in white collar jobs, were believed to be more prone to neurasthenic shocks and breakdowns because, Beard posited, they were “more exposed to numerous sources of cerebral excitement in the worry and turmoil of the world.” Because blue collar men already engaged in physical labor on a daily basis, they were thought to be immune. Male office workers were told to reduce their sexual activity, including masturbation (women, on the other hand, might be prescribed sexual release, administered by her physician). They were also counseled not to tax their brain too much in order to avoid depleting their nerve forces, and to engage in physical sports and exercise to channel their energy in a healthy way.

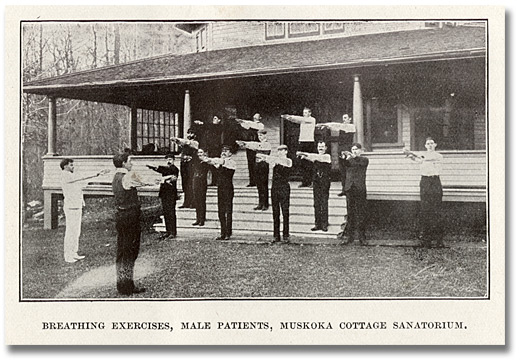

Sufferers of neurasthenia would sometimes check into a sanitarium, in the hope that a regimen of fresh air, healthy food, and exercise would cure their anxiety and restore balance to their nervous system.

In extreme cases of neurasthenia, the sufferer would check into a sanitarium, where they were put on a regimen of healthy eating, exercise, fresh air, and plenty of enemas to replenish their nerve force. Snake oil hucksters, seeing an opportunity to make a quick buck, even concocted “brain and nerve” pills to sell to those afflicted by the modern malady.

The Victorian emphasis on neurasthenia was part of a larger shift in thinking about the nature of melancholy. Up until this point, the condition was seen as a defect of the intellect, the brain, or the body. But beginning in the middle part of the 19th century, it began to be seen as disorder of the emotions. While at first blush this change in emphasis may appear subtle, it’s actually pretty significant. This new viewpoint fundamentally changed how doctors and psychologists approached the treatment of depression; instead of just the body and mind affecting emotions, or more accurately moods, one’s emotions were seen as affecting the body and mind. This perspective would give rise to “mood science” in the 20th century and had a significant influence on the modern approach to depression.

Alongside this shift to viewing melancholy as a mood disorder, came a change in the nomenclature used to describe its manifestations. During the 19th century, one of the symptoms of melancholy (and its closely related sister, neurasthenia) was “depressed spirits” or “depressed emotions.” Gradually, doctors began describing a person suffering from melancholy as experiencing mental or emotional depression. While “depression” didn’t replace melancholy as a way to describe the mental disorder until the middle of the 20th century, the process got underway a century prior.

Finally, in 1895 German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin made significant and lasting contributions to the approach and treatment of mental health by becoming the first to separate manic depression and schizophrenia as well as formally categorize types of melancholy based on severity. He also proposed a biological and genetic basis for the “depressive state” and argued that treating melancholy required medical intervention.

Early 20th Century Freudianism

Psychoanalytic therapists posited that the source of depression and anxiety was found in the unconscious, and could be managed by talking about one’s childhood experiences and other events that had shaped the individual.

Competing with Kraepelin’s psychobiological view of melancholy was Freud’s psychoanalytical approach. In his essay “Mourning and Melancholia,” Sigmund Freud argued that while mourning (defined as the grief following loss) and melancholy had the same symptoms of depressed mood, melancholy was a depressed mood without a cause, or at least an unknown, unconscious cause. Mourning could be recovered from without intervention by allowing the person to go through the natural grieving process. Melancholy, on the other hand, required psychoanalysis to suss out its subliminal roots.

Other Freudian psychoanalysts argued that melancholy at its core was a type of narcissism. Sandor Rado believed that melancholics were simply seeking approval and affection from various “love objects,” and that melancholy resulted when that love wasn’t reciprocated. Melanie Klein and others hypothesized that melancholy was the result of rejection by the mother; the more intense the hostility from the mother, the more intense the depression.

Bridging the gap between Freud’s psychoanalytical view of depression and Kraepelin’s psychobiological view was Adolf Meyer. Meyer proposed that early childhood experiences as well as genetics could make someone more prone to melancholy. However, he also believed that past experience and genetics weren’t destiny; a person could live their life so they were less prone to mental illness. He also made the case that depression and not melancholy should be used to describe the condition of severe and prolonged low-mood. So thanks to Meyer, “depression” became the clinical term that is used today.

Mid-20th Century to Today

By the middle of the twentieth century, advances in neuroscience had given psychiatrists and psychologists unprecedented insights into how the mind works. For example, they learned that both chemicals and electricity make up brain activity, that different parts of the brain are responsible for different behaviors, and that modifying these things could change how a person acted and felt. With this understanding, treatments like electro-shock therapy and lobotomies were performed in the hope of curing, or at least dampening, depressive moods.

Another major development of the 20th century was the creation of formal categories to classify various mental illnesses. To help standardize and treat mental illness as more akin to biological disease, psychologists and psychiatrists put together the American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1952. In the first edition of the DSM, the term melancholy was replaced with depressive reaction to describe a severe low mood resulting from an internal conflict or an identifiable event like job loss or divorce.

At the same time psychologists were classifying mental illnesses, pharmaceutical companies were stumbling upon drugs that could alter mood. During the 1950s, tranquilizers became a popular treatment for anxiety, and Miltown and Valium became cultural touchstones in mid-century America. The idea that drugs could be used to alter undesirable mental states would pave the way for their development and acceptance in treating depression.

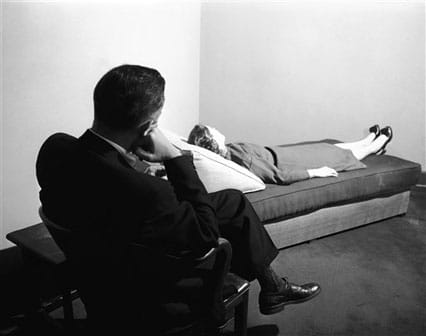

Until such pharmaceutical discoveries could be realized, however, Freudian psychoanalysis remained the predominant approach to mental illness. Up through the 1970s, if you were having trouble with depression, you’d go lay on the stereotypical psychologist’s couch and engage in talk therapy.

Running concurrently in the culture of the postwar period was a resurgence, at least among artistic types, of the idea that depression was not something that needed to be “cured” with either drugs or therapy but was instead an authentic, legitimate part of one’s identity — a vehicle for inspiration and self-discovery. Mid-century writers like Sylvia Plath, Thomas Szasz, R. D. Laing, and Michel Foucault rejected the idea that mental illness represented an unhealthy deviation that needed to be flattened into a culturally acceptable standard of normalcy.

The development of mood-altering drugs shifted the cultural conception of depression to a disease with biological roots, little different than a physical ailment like diabetes.

This countervailing view, and psychoanalysis as well, however, was soon eclipsed by the ascendancy of the psychobiological approach to mental illness. Drug companies and psychological researchers began putting forth evidence that depression was simply a chemical imbalance in the brain that targeted drugs could remedy. They often analogized depression to a physical disease like diabetes. The problem was biological and clear-cut; just as a diabetic needs to take insulin to balance their blood sugar, so too must the depressed individual take drugs to balance their brain.

Advocates for the psychoanalytical and psychobiological camps found themselves in increasing conflict, and the debate between them was particularly fierce leading up to the release of the DSM-III in 1980. The DSM-III was intended to improve the uniformity and validity of psychiatric diagnosis as well as make it more symptom-based rather than cause-based. The Freudians were more interested in treating the underlying psychological causes of mental illness, while the psychobiological camp argued that they could treat the symptoms with drugs. Each side wanted to see the DSM emphasize their approach.

Also debated were the new categories of mental illness that were created to assist clinicians in making clear diagnoses for insurance purposes. Drug companies pushed for the new categories because under FDA regulations, pharmaceutical companies could only market and sell drugs that targeted a specific disease. With more categories recognized as a disease, pharmaceutical companies could make and sell more drugs. And that was indeed the result: drugs targeting serotonin in the brain proliferated after the release of the DSM-III. Prozac began selling in the U.S. just seven years after its publication; Zoloft in 1991, Paxil in 1992, and Celexa in 1998. In just over 30 years, the number of Americans taking anti-depressants went from around 2.5 million in 1980 to forty million today. That’s a 1500% increase.

The final version of the DSM-III is often seen by psychology historians as a victory for psychobiologists and a huge defeat for psychoanalysts. Major Depressive Disorder was added as something separate and distinct from anxiety or neurosis. To be diagnosed with MDD a patient had to satisfy three criteria: 1) dysphoric mood (sad, feeling hopeless), 2) at least four symptoms from a list that included things like lack of hunger, sleepiness, low energy, loss of interest in normal activities, and excessive guilt, and 3) the symptoms had to last at least two weeks (in the original draft symptoms needed to last for a month, it was changed to two weeks without explanation). In addition to MDD, other depressive categories were adopted including dysthymic disorder, which is characterized by a light, but prolonged low mood.

The DSM created lists of criteria for mental disorders and made them easier to classify and diagnose. It may have also led to over-diagnosis and an emphasis on the symptoms of depression rather the causes.

With the DSM-III, the diagnosis of depression became a matter of simply checking off the listed criteria. Patients could now go to their family doctor (instead of a psychiatrist) and be diagnosed with depression and walk out with a prescription to help alleviate the symptoms. But while diagnosing depression became easier, it may have become too easy. DSM-III didn’t strongly distinguish between normal sadness and depression, and it didn’t take into account life situations like divorce or loss of a job that would typically put someone into a funk. As a result, many people began seeking treatment for depression who might otherwise have chalked up their low mood to “normal” sadness. Even with the clearer diagnostic criteria, research has shown that doctors still reach different conclusions on how to diagnose a patient in experimental settings (in which doctors are given a hypothetical list of symptoms and asked to reach a diagnosis).

Ultimately, while the medicalization of depression helped reduce some of the stigma surrounding the “black dog,” it may have inadvertently pathologized normal emotions and behavior and gotten millions of Americans on drugs who perhaps don’t need to be. (In our last post on possible treatments for depression, we’ll go more in-depth about the effectiveness of anti-depressants; short answer: it works for some people, but not everyone.)

Along with the rise of pharmaceuticals to treat depression, new forms of therapy developed during this time as well. Instead of the more drawn-out and abstract psychoanalytical approach that often took years, the new theories emerging in the late 20th century were more concise and geared towards immediate results. The most prominent new therapy was developed by University of Pennsylvania psychiatrist Aaron Beck in the 1960s. Called cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), this form of talk therapy is based on the premise that depression is caused by faulty, negative cognitions. The goal of CBT is to help the depressed individual challenge those faulty thoughts and replace them with ones that line up more closely with reality. While CBT and other talk therapies have gained awareness in the public, few Americans suffering from depression seek them out as they’re costly from a time and monetary perspective. For many people, drugs are just more convenient and efficient.

The DSM-IV, released in 2000, made a few changes in the diagnosis of depression by adding grades. So one could be diagnosed with mild depressive disorder if they met two of the symptoms of major depression instead of four. It also explicitly excluded a person from being diagnosed with MDD who was reporting low mood caused by the loss of a loved one. DSM-V, published in 2013, did some re-categorizing to help mitigate possible over-diagnosis of depression, though critics say it failed in achieving that goal for a few reasons. For starters, the bereavement exclusion was removed so now individuals who are grieving the loss of a loved one could be diagnosed as clinically depressed (the idea of also including grief as a mental disorder in and of itself was suggested and debated, but ultimately not included). The DSM-V also re-categorized dysthymic disorder (low-grade, prolonged depression) as prescient depressive disorder.

And that is where we find ourselves today.

Conclusion

As you can see from our barnstorm through the history of depression in the West, society’s views of its nature and treatment have varied widely over time, and often moved back and forth like a pendulum. Balancing humors has turned into balancing neurotransmitters. Right thinking through Stoicism has become right thinking through cognitive behavioral therapy. The conception of depression as a vehicle for insight into the human condition, waxed and waned, and is now out again. Our understanding of depression has hardly been stable, definitive, or linearly progressive.

This doesn’t mean that depression is a cultural construct, but rather that culture affects how a society views and approaches depression. Research on the prevalence of depression in different parts of the world bears this out. For example, academic psychiatrist Nassir Ghaemi notes in his book On Depression, that “only 1 percent of the population in Taiwan can be diagnosed with major depressive disorder [using the standards set by DSM-IV], that is having had a major depressive episode at some point in life; almost 20 percent of the population in Paris meet that definition. It’s about 1 percent in Iran, about 5 percent in the United States, 10 percent in Canada.” This disparity is striking in and of itself, more so when you consider that other mental illnesses, like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, show up in 1% of the population no matter the country.

What’s more, the rate of depression in the U.S. has increased dramatically over the last century. In 1905, just 1% of Americans reported a major depressive episode by age 75. In 1955, 6% experienced a major depressive episode by age 24. Today, according to some reports, 10% of the adult American population, or about 30 million people, experience depression at some point during any given year. While there are several possible reasons for this uptick in depression (and we’ll unpack those in the next post), our culture’s changing approach towards the malady (and sad moods in general) certainly is a factor. Is new awareness about depression helping more people get the help they wouldn’t have gotten 100 years ago? Or is modern life just depressing? Is part of it simply that our culture’s emphasis on happiness and extroversion gives people the impression that they’re clinically depressed because they’re not gleefully ecstatic all the time?

The bottom line is that it appears something is going on at a cultural level that’s causing rates of reported depression to go up. And that’s partly because we’re still wrestling with the same questions people have grappled with for thousands of years. Is depression more biological or psychological or environmental? Can changing your thinking cure your depression? What’s the connection between mind, body, and spirit? Is depression an unmitigated bad or can it have its consolations? Is depression an intrinsic part of one’s true self, a tool to finding one’s true self, or an obstacle to being one’s true self?

These days we lean towards answers that emphasize the biological and genetic, and take the view that depression must be attacked and rooted out immediately as if it were an invading virus. But even as I write this, theories that have dominated the field for the last two decades are being upturned. We would do well then to remember that experts in every time period have felt as sure about their theories as we do about ours. In a thousand years, the idea of taking a pill or talking on a couch to alleviate depression may seem as laughable as balancing one’s black bile.

All of this uncertainty may seem, well, rather depressing. But it can also be quite liberating. Being told there’s one right way to view and handle your depression, and trying that approach without success — now that’s really depressing. Rather than being shackled to one path, and one perspective, might it not be better to take a multi-faceted approach, and to embrace the freedom to experiment with what works for you? To step outside the idea that everything that’s come before is wrong, and that how we see depression now is the only way to look at it?

Because it’s not that we don’t know anything, and that we’ve been groping along completely blind since antiquity. Right thinking, physical exercise, long walks, good conversation, rugged living, drugs, heck, even bloodletting(!), might be just what the doctor ordered; and the wisdom of the ancients coupled with modern insight might be the best way forward. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves aren’t we? For now let’s leave the black dog’s past behind us, and get ready to move into the current thinking on its possible origins next week.

Read the Rest of the Series:

My Struggle With Depression

What Causes Depression?

The Symptoms of Male Melancholy

How to Manage Depression

Also be sure to listen to my podcast with Dr. Jonathan Rottenberg on the origins of depression:

______________________

Sources and Further Reading: