Ol’ Blue Eyes, the Chairman of the Board, the Voice.

Frank Sinatra has been an icon of masculine coolness and swagger for decades. During his lifetime, he was able to create a myth and legend around himself that continues to exist today. But, like all legends, when you look closer at them, you discover that the reality is much more complex than the story.

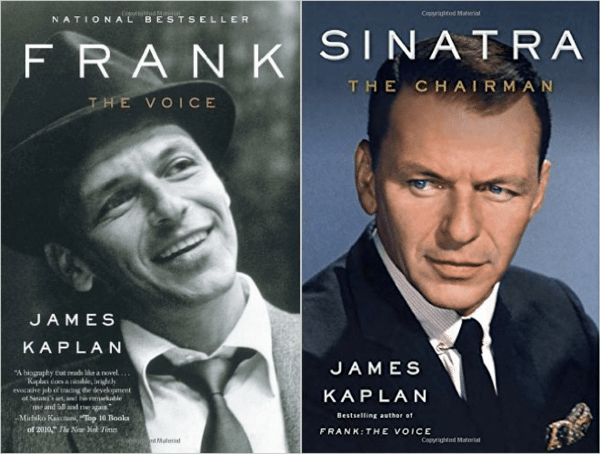

Today on the podcast, I talk to James Kaplan about Sinatra’s complex life. Kaplan is the author of a definitive two-book biography of Sinatra and recently published the concluding volume: Sinatra: The Chairman. On the show, James and I discuss how Sinatra’s career went in the tank after World War II, and what he did to not only revitalize it, but catapult himself into legendary status. We also get into Frank’s foibles, his incessant drive for power, and his enduring appeal as an icon of American masculinity.

Show Highlights

- Why Frank Sinatra was both the most popular and most despised man in the military during WWII (04:00)

- Why music in America got really terrible after the war (06:00)

- How Frank Sinatra went from being one of the biggest stars in America to not being recognized in Times Square (07:00)

- How Frank Sinatra revolutionized American music, created the pop standard, and catapulted himself to legendary status (12:00)

- The music arranger that helped Frank create some of his biggest hits (15:00)

- How Sinatra was different from other crooners of his era (18:00)

- The source of Sinatra’s personal demons and the problems they caused in his life (22:00)

- Why Sinatra was drawn to the mob (26:00)

- The time Frank Sinatra started a fight with John Wayne while dressed up like a Native American woman (28:00)

- Why Sinatra was so power hungry and how it ruined his life (32:00)

- What drew Sinatra and JFK together (37:00)

- Sinatra, Kennedy, and the mob (42:00)

- How the Rat Pack got its start at the Sands Hotel (47:00)

- Why Sinatra will always be an enduring icon of masculinity (54:00)

- And much more!

Resources/People Mentioned in Podcast

- Kaplan’s first volume on Sinatra — Sinatra: The Voice

- Goodbye, Darkness by William Manchester

- Westbrook Pegler, the Hearst columnist that went after Sinatra for his links to the mob

- Ava Gardner, Sinatra’s second wife and on-again, off again lover

- Nelson Riddle, the music arranger responsible for many of Sinatra’s hits

- Dolly Sinatra, Frank’s mother

- Sam Giacana, Chicago mob boss

- Judy Campbell, mistress of both JFK and Giacana. Sinatra introduced her to both men

- From Here to Eternity (Sinatra won a Best Supporting Oscar for it)

- The Rat Pack

- Sammy Davis, Jr.

James Kaplan’s Essential Frank Sinatra List

James was kind enough to put together his list of essential Sinatra albums along with the best song from each. If you’ve never listened to Sinatra, start off with these.

- In the Wee Small Hours (1955): “What Is This Thing Called Love?â€

- Songs for Swingin’ Lovers (1956): “I’ve Got You Under My Skinâ€

- Come Fly With Me (1958): “Come Fly With Meâ€

- Ring-a-Ding Ding (1960): “Ring-a-Ding Ding”

- Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim (1967): “Dindiâ€

Sinatra: The Chairman is an engaging and nuanced look at a fascinating and complicated man. Besides learning about the life of Sinatra, you’ll get a good dose of mid-century American pop-culture history as well.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Ol’ Blue Eyes, the Chairman of the Board, the voice. Frank Sinatra has been an icon of masculine coolness and swagger for decades. During his lifetime, he was able to create a myth and legend around himself that continues to exist today. But, like all legends, when you look closer at them, you discover that the reality is much more complex than the story we like to tell ourselves. In reality, Frank Sinatra’s life, very, very complex.

Today on the podcast, I talk to James Kaplan about his concluding volume of his definitive biography on Frank Sinatra. It’s entitled Sinatra, the Chairman, and on the show, James and I discuss how Frank Sinatra’s career went in the tank after World War II, and what he did to, not only revitalize it, but catapult himself into legendary status. We, also, get into Frank’s foibles, his incessant drive for power, and how that connected JFK and the Mob together, and we talked about Frank’s enduring appeal as an icon of American masculinity. A great show.

When you’re done, be sure to check out the show notes for this podcast at AOM.IS/Sinatra. You’ll find links to people and stories mentioned in this episode, as well as a suggested Frank Sinatra playlist from James Kaplan, Frank Sinatra’s biography.

James Kaplan, welcome to the show.

James Kaplan: Delighted to be here, Brett. Thanks so much for having me.

Brett McKay: Your second biography, your biography of Frank Sinatra came out last year. It’s called the Chairman, the subtitle, and it picks up right after Frank Sinatra won the Academy Award for best supporting actor for From Here to Eternity. You talk about in the book that before he won this award, Sinatra’s career was pretty much in the tank. I’m curious, can you give us a little back story? How did Frank Sinatra, going from making thousands of bobby soxers faint during World War II, to people couldn’t even recognize him on the streets in New York City?

James Kaplan: Yeah. Well, the book that just came out was the second volume of my biography of Sinatra, second and final. The first volume was called Frank, the Voice, and covered his rise to incredible superstardom, mainly during World War II.

World War II was really what jet propelled Frank Sinatra’s career to its apex during those years, because, in that time, he was singing these ballads of yearning that so rhymed with the way the country was feeling, feelings of gentle sadness and missing the boys who were away fighting overseas. Of course, Frank was not away fighting overseas. He had been classified 4-F. A lot of people suspected that, and called him a draft dodger.

William Manchester, who wrote a great history of the Armed Forces in the South Pacific in World War II, where he, also, served very bravely as a Marine, said that Sinatra was the most despised man in the Armed Forces, because all the guys fighting overseas felt that Sinatra, the draft dodger, was back at home fooling around with their women, and, in many cases, they were right. He wasn’t a draft dodger. He really did have a punctured ear drum, but the perception lingered.

Despite the perception though, he sold a ton of records in World War II. After the war, very, very quickly things changed in America. The political climate became very conservative, and the popular culture of America really became extremely conservative after World War II, and tastes in popular music shifted gears just like that overnight. Suddenly, people were no longer interested in the ballads of yearning. Suddenly, the Big Band era, which had begun ten years previously in about 1935, began fading away very quickly, and America was in this odd state of jubilation and fear. Jubilation because the war was over, and fear because of the rise of the Soviet Union. That accounts for the political conservatism, and, also, I think the popular culture, too.

Popular music really got pretty terrible in the wake of World War II very quickly. There are all kinds of novelty songs. People wanted escape after World War II, so they were listening to stuff like How Much is that Doggie in the Window, and Sinatra, who was still recording for Columbia at that point, but, unlike every other popular singer, had enough power to dictate what he could record. Still, he decided to go along with the tide. He did record a number of these crummy novelty numbers, Tennessee Newsboy, most infamously the worst record he ever made, Mama Will Bark.

His career, after World War II, went down the tubes for a few reasons. It wasn’t just that tastes in popular music had changed. It was really a multi-determined problem, and a lot of the problems Frank created for himself. He was, in 1947, early 1947, he went to Havana, Cuba to attend a Mafia Summit Conference. Officially he went because he was there to entertain all these top mobsters. It’s, also, been alleged over the years, that he brought a suitcase packed with cash for Lucky Luciano, as tribute, and he was sighted in Havana by a columnist for the Hearst papers, and this columnist began to write disparaging columns about Sinatra’s affection for the Mob. The Hearst papers were very politically conservative. Again, chiming with the times. Frank was a dyed in the wool liberal Democrat. He was an FDR Democrat. The Hearst papers hated him for that, and, suddenly, they had something to call him out for.

That wasn’t enough for Frank. He, also, from the day he set foot in Hollywood, he began stepping out on his young wife, Nancy, with all kinds of Hollywood starlets, and in 1948, ’49, he stepped that up. He was sighted with Lana Turner, and then he began this famous affair with Ava Gardner, and in 1951, his wife changed the locks on the house and divorced him.

That wasn’t all. His record label, Columbia, dropped him, because he wasn’t selling records. His movie studio, MGM, dropped him for various reasons, but they had gotten tired of him at that point. His agents dropped him. He wasn’t selling records. He wasn’t really making movies.

He married Ava in 1951, but his career was sinking just as fast as her career was rising, and, as crazy as they were for each other, Frank and Ava, she began to get sick of his moping around, and so his marriage wasn’t even working well then. It was a perfect storm of events, and, again, Frank himself had a lot to do with almost all of them.

Brett McKay: He’s at the bottom of his career, the lowest of lows. From what you’ve read and researched about him, did he purposely think, “I got to do something about this. I got to do something to kick start my career.” I mean did he deliberately start thinking about how he could catapult himself back into …

James Kaplan: Constantly, constantly. The most important thing to Frank Sinatra throughout his entire working life, from the time he first started singing professionally in his very early twenties, then went on the road with Harry James and then Tommy Dorsey, then went out on his own as a singer, through his decline, into his comeback, and until the very end of his singing career … The last concert he ever sang was in February 1995, after an incredible sixty year career. Every minute of every day, Frank Sinatra was thinking about his singing and about his career. That was his priority, and so you can bet that during those years of decline, he was obsessing every waking minute about how he could come back.

Easier said than done though. Easier thought about than done. He was incredibly frustrated, incredibly depressed. This is a period when he made a couple of the first of his three suicide attempts. He was as low as you could get, and, yes, as you said before, this is a point when he could walk through Times Square in New York, where in 1944, he had created a mob scene around the Paramount Theater with those fabled bobby soxers. He could walk unnoticed, unrecognized. Sammy Davis, Jr. Happened to be in Times Square and saw Frank walking through with his collar up, and nobody recognized him.

Brett McKay: Wow. You said that after World War II, the music taste changed during the 1950s, but during the ’50s, this is where a lot of the albums that we listen to today came out, a lot of the songs that he recorded. It’s kind of weird time, because, like you said, the Big Band era was over, but, yet, rock and roll was just starting. What did Frank Sinatra tap into, into the American taste in music that people were like, “Yeah, this is great. We like what he’s doing.” How as it different from the Big Band stuff, but how was it, also, different from rock and roll?

James Kaplan: Well, Sinatra did more than tap into. Sinatra really created a revolution in popular music. Rock and roll, of course, was its own revolution in popular music. Rocket 88, that historic cut, was recorded in 1951, and rock and roll was on its way, headed straight up. Elvis would be walking down the street in just a couple of years after Rocket 88, and meeting Sam Phillips historically at Sun Records in Memphis, but Sinatra created his own revolution in popular music. It wasn’t so much a tapping into.

Let’s step back a couple of years, and remember that between the end of World War II and around 1952 or 1953, people were just buying a lot of junk. It was all this very transitory, transient, ephemeral music, that just kind of feel good, Doggie in the Window.

Brett McKay: Hokey Pokey.

James Kaplan: And Mitch Miller over at Columbia had Sinatra recording these crummy novelty numbers, and he had other great artists like Rosemary Clooney, was recording Mambo Italiano and Come On-a My House. It was all honky tonk, hurky jerky silly music.

Sinatra was dropped by Columbia Records. They failed to renew his contract in 1951, and he drifted without a label for a couple of years. In 1953, and the importance of this cannot be over estimated, an incredibly far sighted young executive at Capital Records out in Hollywood, a young guy named Alan Livingston, decided to sign Sinatra. He signed Sinatra because he knew how talented, incredibly talented Sinatra was, and he had some ideas, Alan Livingston did. He signed Sinatra to a standard artist, beginning artist contract for a sum in the three figures, low three figures. We’re talking a couple of hundred dollars, and when Alan Livingston told his Capital Records sales force that he had just signed Frank Sinatra, a room full of a couple hundred salesman for Capital Records, they all groaned.

This guy was such a drug on the market at that point, but Livingston’s idea was he wanted to team this incredibly talented singer, whose talent Livingston recognized, despite how down on his luck Frank was. He wanted to team Sinatra with a young, totally unknown arranger, a guy named Nelson Riddle, who I’m sure many of your listeners have heard of, but then nobody knew who he was. Frank Sinatra didn’t know who he was. He teamed up Sinatra with Nelson Riddle, and they recorded a number very early in their collaboration together called I Got the World on a String, and when Sinatra heard the playback of that number that he had just recorded with Riddle’s incredible arrangement, because this guy could arrange like nobody else, Sinatra said, “I’m back, baby. I’m back.” He knew it. He knew it, and he knew he had it with Nelson Riddle, and he and Riddle began to turn out these singles and these albums that created, as I said, a revolution in popular music.

Let me just say one more thing about that revolution, because this is very important to understand. We talk today about the great standards, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, the Gershwins, the great American songbook, all these amazing numbers that stand the test of time, so beautifully constructed that modern artists keep recording them over, Lady Gaga, Buble, and people will continue to record them for decades and centuries to come, because they are great and they’re classic.

Sinatra was the one who really created the idea of the standard. These songs were not being recorded before Sinatra insisted. At the end of his Columbia Records career and at the beginning of his Capital Records career in 1953, Sinatra insisted on recording them. When he performed them in concert, he would always credit the great songwriters.

It’s a long winded answer, Brett, to your question, but I do want to say that it wasn’t Sinatra feeling the pulse of America. Sinatra was creating the pulse of America. This was a great transformative artist, who had ears, who had a musical understanding on a Mozartian level, and knew what he wanted to do with popular music, and created a revolution.

Brett McKay: Yeah. That leads to my next question, because I thought it was interesting. What I love about your book, James, is that you take us into these recording sessions, and talk about the dynamic between Sinatra and the arranger and the orchestra. I think it’s interesting, because I think maybe a lot of people today think of Sinatra as pop stars of today, that he had a nice voice, and he just goes in and sings the songs that the musicians wrote, and that’s it, but the way you describe the recording sessions is like Sinatra was almost a conductor, almost, and he was making these little improvisations, and he could just tell right away that the violins need to do this. Was he different from some of the other popular crooners during the time, because of his musical ability?

James Kaplan: Yes. He was absolutely different. This was a musical genius. This was a guy who knew exactly how he wanted those recordings to sound. We talk about record producers. The great George Martin just died a couple of days ago, and a great, great producer, and producers today, people like Nile Rogers and Pharrell Williams, these are people who go into a studio and shape every bar of every song, every second of every track that’s recorded.

Sinatra had people who were called producers, but Sinatra really produced all his own albums and all his own singles. He was the guy who knew exactly how he wanted these records to sound. He was the guy who had such incredible ears that if the third violin in his orchestra, and Sinatra, by the way, was a guy who revered musicians. He never wanted to be in an isolation booth singing when he was recording. He always wanted to be out there with the musicians. If the third violinist was a half note off, he would look. He would stop the music, and freeze the guy with a glare from those electric blue eyes, and say, “Where are you working next week?” Sinatra knew exactly how he wanted these songs to sound, and despite the fact that this was a guy who really couldn’t read music, he couldn’t read, he still knew his way around a score, and so he could say, “Bar forty-five, shouldn’t that be maybe an F natural instead of an F sharp.” He knew stuff like that.

We, also, have to remember that these songs he was recording, unlike the songs of today, all came from written arrangements. These were charts. These were very detailed arrangements that were written by great arrangers, such as Riddle, and Billy May, and Sinatra worked with dozens of terrific arrangers, up to Quincy Jones, and Claus Ogerman, and Don Costa, and Gordon [Shankins 00:20:25]. These were all brilliant men, with whom Sinatra purposely allied himself. He hired these guys, because he knew what they could do for him, but Sinatra was the boss.

Brett McKay: Right. I mean I love Sinatra’s music. I listen to Sirius Sinatra on Sirius XM radio all the time, but the thing that I’ve always been conflicted about the guys, because he’s an extremely complex character. Super talented, I love his music, but then you do such a great job in the book painting the complexities of Sinatra. The man had a lot of paradoxes about him, and as you said earlier, some of these … The darker side of Sinatra, caused him problems with, not only his family life, his love life, but, also, his career, so can you talk about some of these personality paradoxes, and how that affected friendships, business associates, and even his lovers, and his wife, and ex-wives.

James Kaplan: Yeah. There are a few things you have to talk about when you’re talking about Sinatra’s personality. As you say, this was a musical genius, but he was, also, a guy who, also, had a genius for making himself dislikable, and I spent ten years writing these two books about Sinatra, and there were a lot of times when I disliked him when I was writing about him, but I never got bored with him. He was never boring.

There are a few things you need to talk about when you talk about the demons that were inside Sinatra. One big one was his mother. His mother was named Dolly Sinatra. She was a volcano. She was under five feet tall, a little tiny woman, who was brilliant. Swore like a sailor. She was a Democratic Party organizer in Hoboken, New Jersey, where Frank grew up. She spoke every dialect of Italian when she went around Hoboken getting out the vote for Franklin Delano Roosevelt. She had a volcanic temper. She was pathologically impatient, and Sinatra, in many ways, was the same person as his mother.

This was a mother who Sinatra later said he never knew whether she was going to hug him or hit him, and that was literally true. He was never certain of his mother’s love for him, and that really conditioned his relationships for the rest of his life, especially with women. His younger daughter, Tina Sinatra, wrote a wonderful memoir, and wrote in her book, “My father was a deeply feeling man, who was unable to attain an intimate relationship with another human being,” and that included all the many hundreds, if not thousands, of love affairs he had. He loved women in a lot of ways, but he never really loved. It was very, very difficult, if not impossible, for him to be intimate with somebody else.

Then you have to add all that, all that that I just said, to the fact that this was a kid who was a musical genius. He said in later life that when he was walking around as a kid, he heard the music of the spheres. Well, that sounds very high flown and exaggerated, but I think it was literally true. This is a guy who heard sounds in his head that other people didn’t hear. There he is, walking around Hoboken, New Jersey in the 1920s and the 1930s, a very tough town, where if an Italian kid walked across the wrong street into the Irish neighborhood, he would get the crap beaten out of him, and this was a kid who was a genius. That was not easy to walk around with, so he had to keep that hidden. He was a highly strung guy, very over sensitive. He had to keep that hidden. He always wanted to seem tough. That was important in Hoboken when he was a kid. It was important when he had grown up.

The toughest guys of all, when he was growing up in Hoboken in the ’20s and ’30s, as an Italian American kid, when Italian Americans … One of the things I learned writing these books, it’s easy sometimes to feel this reflexive nostalgia for the way America used to be. “Oh, things were better in the old days when men were men and women were women,” and some of that’s true. There was a lot that was very bad in this country in the old days, and the very worst thing that I found was this very easy reflexive racism that existed in this country, and there’s still a lot of it around, but it wasn’t even questioned in those days. If you were a white Anglo-Saxon protestant male and you had some money, you could be in the ruling class. If you didn’t, you were out of luck, and Italian Americans were just a half a step above African Americans on the social scale. Italian Americans, like African Americans, were looked on as happy, singing, dancing people, and, also, who now and then murdered people. They were either clowns or they were mobsters.

That was rough for Frank to live with, but as soon as he began performing in clubs, he began running into these guys, who ran the nightclubs in those days, and they were the Mafia. The Mafia ran the nightclubs, and a lot of them were Italian American, the mobsters, and Frank idolized these guys. They were men of power. They were men of strength, and he saw them, incorrectly, but he felt they were men of honor, too.

This is a guy who was full of demons, and this is a guy who is highly strung, and over sensitive, and a musical genius, and whose mother didn’t really love him, and boo hoo, that sounds sad, but if it happens to you, it’s real, and it happened to him. He couldn’t really form an intimate relationship. He was too highly strung, and once Ava threw him over … Ava Gardner threw him over in the early fifties, he began to drink pretty seriously. Alcohol became a big part of his life, and he was a mean drunk. He was an angry drunk, and he had all these demons inside, and when he drank, the demons would come out.

There is an answer to your question. There are an awful lot of things inside Sinatra that were bugging him and they could make him behave very badly.

Brett McKay: Right. I mean going back to the volatility, you had these … You describe encounters where he would go after men who were like twice his size. There was an encounter where he went after John Wayne in the parking lot …

James Kaplan: Yeah, unbelievable. Frank Sinatra was five foot seven, five foot seven in his stocking feet, and until he put on some weight in his fifties, he was a guy who weighed maybe in the one twenties, one thirties. He’s a little man with thin wrists and delicate hands, but he had this volcanic temper, same as his mother did. He was pretty fearless, and when he was in his cups, when he had a couple of drinks in him and he was feeling angry about something, yeah. He went right up against John Wayne, and you’re talking about a guy who was six foot four, and who was a genuine tough guy. Frank wasn’t afraid for a second standing in front of John Wayne, and John Wayne didn’t want to fight Frank Sinatra. It wasn’t that he was scared, he just didn’t want to fight him, to his credit.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I thought it was funny. The circumstances of the fight, there’s a dose of irony to it, because it was like at a party in Vegas.

James Kaplan: A benefit.

Brett McKay: And Sinatra was dressed like an Indian squaw.

James Kaplan: Yes, he was. This in the old politically incorrect terminology, yes. We’re not allowed to say that anymore, but that was how he was dressed.

Brett McKay: That’s how he was dressed. That’s how you would say he was dressed.

James Kaplan: As an Indian woman, a Native American woman, and there is Wayne, the Duke. He’s six foot four in his stocking feet, and he’s got on the cowboy hat, which makes him about six foot nine, and there they are facing off in a parking lot.

Brett McKay: Yeah. This personality of Sinatra’s … You had the issues with his mother, and he’s volatile. He seems like he had a chip on his shoulder.

James Kaplan: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Being an Italian American, and he was talented and he knew it. The theme that you see throughout the book, and I think all these three things come together with it, is that Sinatra was very interested in power, not only in business, but it, also, carried over into he wanted to get into the political arena. We can talk a little bit more about his relationship with JFK, but why was he so obsessed with power? Did he have some common tactics for power pulls that he would use on people to get what he wanted?

James Kaplan: Well, power was always important to him from the beginning. Again, this is a guy who, as a kid, had felt himself to be weak, had felt himself to be one down as a small person, as an Italian American, as a guy who knew he had the goods to become the best popular singer of all time, but, at first, nobody knew it but him. This is a guy who had to learn to throw his weight around. Power was very important to him, commercial power, the power of his career. When he first broke through after he went out on his own as a popular singer, and became a superstar, and then went out to Hollywood and signed with MGM, and quickly became one of the hottest stars around Hollywood in the ’40s, he knew he had power, and that power meant an enormous amount to him.

When his career declined after World War II for that terrible period between about 1946 and 1953, when he signed with Capital Records and began shooting From Here to Eternity, the movie that would win him the Oscar, and that Oscar would begin his comeback. During that terrible period, that seven years of bad luck, when he said it felt like every day was Monday, he felt acutely what it was like not to have power, to lose power, to be powerless, to have had it … I mean it’s one thing to have never had power and to yearn for it, but imagine having the kind of power he had, then completely losing it and being looked on by everybody as a loser, a failure, a has been.

It was very important for him to get it back when he began to get it back, when he began making those sublime albums with Nelson Riddle, when he began shooting that great movie, From Here to Eternity, and then, suddenly, he went from zero to sixty, and, suddenly, the offers were all pouring in again, and movie offers, singing offers, TV offers, everything. Very, very quickly, as the offers poured in, the money came in, and the power began to increase. He held onto to everything he could grasp, and he relished the acquisition of power.

The paradox of it, Brett, is that the more power he got, and it’s really kind of like the legend of Midas, the fabled king, everything he touched turned to gold, but then he had nothing to eat. He had nobody to love, because it was all just gold. Sinatra was very much like that. He acquired all this enormous power, financial power, power in popular music, power as one of the top movie stars around, and, yet, he couldn’t really get close to anybody else. It was a source of terrible sadness to him, and it was a sadness that he tried to drink away, that he tried to party away, that he tried to sing away, but it was a sadness that he really couldn’t banish. The power was enormous, and it was very important to him, and, as I said, he loved it, but he couldn’t figure out how to hold onto the power and be truly happy at the same time.

Brett McKay: Was that desire for power, is that one of the things that drew him to the mob?

James Kaplan: Yes. It was certainly one of the things that drew him to the mob. He saw these guys as powerful guys, and he saw them really as America’s … Kind of a shadow power in America. You had the government. You had the corporations, and the Mob had an awful lot to do with running American in the 1920s, ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s. They’re still around today, but in a more complicated more, and there are more different kinds of mobs, but, back then, it was the Italian mob, and to a somewhat lesser extent, the Jewish mob, and they ran the nightclubs. They ran the record business. They ran a lot of businesses.

Sinatra, as I said before, idolized them, and loved to hang out with them, and, in some corner of his soul, kind of would have loved to have been one of them. He wasn’t. He was who he was. It was the same attraction to power that drew him to Jack Kennedy the first time he ran into him in 1955.

Brett McKay: The power was what drew Sinatra to Kennedy, but the feelings were not completely mutual. We’ll talk about how Sinatra was really obsessed with Kennedy, and Kennedy was a little more aloof, but why was Kennedy attracted to Frank Sinatra?

James Kaplan: Well, how are we rated here? I’ll try to be discrete. I’ll try to stay PG. Jack Kennedy, from an early age, Jack Kennedy was a brilliantly gifted man in his own right, but he was a prince. His father, Joe Kennedy, had become a mogul in Hollywood in the 1920s. Bought into RKO Studios, and, as a young prince, even before he went off to World War II, Jack Kennedy began going out to Hollywood, and what he loved about Hollywood was women. Hollywood was the center of the universe, the world capital of freakishly beautiful women, and John Kennedy, from an early age, wanted to score with every last one of them, much as Frank Sinatra did.

When they met in the mid ’50s, Jack Kennedy was a politician on his way up. He was, also, married. He had been married for a couple of years to Jacqueline Bouvier, and he was delighted to be married, and, in many ways, took delight in his wife, but Kennedy had a complete double standard, and still saw fit to try to bed every beautiful woman he can. He saw Sinatra as a magnet for beautiful women, and beautiful women were always around Sinatra, because Sinatra had this power in Hollywood, and power and popular music and the nightclubs, and in Las Vegas, and Kennedy found it intensely glamorous, and intensely attractive.

This was his pull to Sinatra. Sinatra had his own rather different reasons for being pulled toward Jack Kennedy.

Brett McKay: Yeah. The way you describe it … Yeah. Like you, I was reading the book, there was moments in the book where I was like, yeah, this is gross, kind of repulsive. I thought it was interesting. In America today, we kind of venerate Kennedy, sort of the whole Camelot thing, but I thought it was interesting that whenever Kennedy came out Hollywood, he’d always shift the direction to Hollywood gossip. He read the gossip rags. You want to know who is sleeping with who, and I thought that was really interesting.

James Kaplan: Yeah. Well, it’s very hard to find really any figure of great stature who is an unmixed blessing. You read about Lyndon Johnson. You read about Franklin Roosevelt. Even Dwight Eisenhower, right. Dwight Eisenhower, the king of the boring fifties, he famously had a mistress during World War II, Kay Summersby. It’s very hard to find figures of great power who are just purely good, and Jack Kennedy was a complicated guy. There is something, I think, to venerate about Jack Kennedy, although his legacy was very tragically incomplete. This is a guy who was a great leader, and who was brilliantly articulate and witty, and, in many ways, could have been a wonderful president, but he was, also, a deeply flawed man, and sex had a great deal to do with it.

Brett McKay: Right. That’s where the mob, like the women, and the connection of women and Sinatra and Kennedy, and that’s where the intersection of the mob came in. That’s where Kennedy got in trouble a little bit, because there was one woman in particular that was, also, seen … One of the top ranking mobsters of the time, and I guess J. Edgar Hoover was really after the Kennedys and had all this evidence. I guess that was the cause of the split between Sinatra and Kennedy, correct?

James Kaplan: Yeah, although the fischer began earlier than that. It even began in the campaign year of 1960, when Kennedy was campaigning against Nixon for the presidency. Kennedy’s family had a lot of misgivings about Frank Sinatra and about their candidate and their golden knight, JFK, associating with Frank Sinatra. Kennedy’s family didn’t like Frank Sinatra’s associations. They knew about his criminal associations, but even more pressingly for the Kennedy family, Frank Sinatra was a guy who was … He wasn’t high class. He was the king of Vegas. He wasn’t a guy that they wanted their candidate associated with, but Jack Kennedy kept associating with him. He clung to Sinatra, because he had … JFK really had this precocious understanding of how important show business could be in politics, of how show business figures could help political figures gain the power that they wanted. It was very smart of him, but his family rebelled against it.

Then once he got into office, a couple of things happened that were very bad and very troubling, and, yes, they centered around one young woman named Judy Campbell, a girlfriend of Sinatra’s, whom he introduced to Jack Kennedy in Las Vegas in 1960, and then very soon afterwards, introduced to his friend, the Chicago mobster, the head of the Chicago mob, Sam Giancana.

In short order, Jack Kennedy was in office as the leader of the free world, the President of the United States, and sleeping with a woman who was, also, sleeping with the head of the Chicago mob. J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI, found out about this, and told the Attorney General, Robert Kennedy, Jack’s brother, about it, and Jack Kennedy, who had been on his way out for some fun and sun at Frank’s place, Frank Sinatra’s place in Palm Springs, very quickly changed his plans when his brother, the Attorney General, told him, “You can’t. You may not stay at Frank Sinatra’s house. You have to cut the cord. No more hanging out with this guy.”

Brett McKay: Yeah. How did that affect Sinatra’s political life afterwards? Was he still heavily in the Democratic Party?

James Kaplan: It was a horrible humiliation for him, that the President, who had been going to stay at his Palm Springs house, stayed instead of Bing Crosby’s house in Palm Springs. Humiliation was always a hair trigger. It was always a point of volatility for Sinatra. It really set him off, any hint of being humiliated. This was a huge public humiliation, and Sinatra never, oddly enough, never blamed Jack Kennedy for it. He blamed Bobby Kennedy for it, but that was really the beginning of the end of his relationship with the Kennedys, and it was the very beginning of the end of Frank Sinatra’s life as a liberal Democrat. He stayed a Democrat through most of the sixties, but by 1968, when Jack Kennedy was gone, Sinatra began to campaign for Hubert Humphrey, who was running against Nixon that year, but Humphrey’s people very quickly found out about Frank’s unfortunate friendships with certain parties in organized crime, and Humphrey dropped him, much as Jack Kennedy had dropped him.

In 1970, Ronald Reagan was running for governor of California, and to the horror of Frank Sinatra’s Democratic friends, his liberal pals, Sinatra supported Ronald Reagan, and that was the beginning of Frank Sinatra, Republican, instead of Democrat.

Brett McKay: Interesting. We can’t talk about this part of Frank Sinatra’s life without talking about the Rat Pack, because I think if were a boy in college, you probably had that famous Sands poster of the Rat Pack in front of the famous Sand sign. It’s a legend, but you’ve talked about the creation of the Rat Pack, that it was almost accidental. Can you tell us a little bit about how that formed, and what went on in the shows, and why did people resonate so much with these impromptu shows that happened in the Sands Hotel?

James Kaplan: It was impromptu, and it was kind of accidental. Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., Peter Lawford, Joey Bishop, were shooting a movie called Oceans Eleven, which became the seminal primary Rat Pack movie. They were shooting that movie in Vegas in early 1960. That was, also, a time when Jack Kennedy loved to … He stopped through Vegas a couple of times during that period, January, February of 1960, because it was just so much fun.

All the guys I mentioned, well the three primary guys, Frank, and Dean, and Sammy, were all booked to open at the Sands Hotel Casino in Las Vegas sequentially in that month of January 1960, but what happened instead, because they were having such a blast shooting this movie, that really was not a very good movie. In fact, it’s a terrible movie, but hugely influential, and it’s kind of like a car wreck, that movie. You can’t quite take your eyes off of it. It’s so influential. Not a good movie, and probably not a good movie because of all the fun they were having shooting it.

Sinatra was the first one booked at the Sands in January ’60, and one night, Dean Martin started heckling him from off stage. Frank, who took his act very seriously, his singing very seriously, Dean Martin always thought too seriously, first was taken aback, but then he laughed, and from that laugh, Dean Martin jumped up on stage, and the Rat Pack was born.

Soon they were all interrupting each other’s act, and soon they were all performing together on stage, and this was at a point, Vegas 1960 is very hard to imagine. You have to imagine your way back into a different time, a different place, a different state of mind. This was a time when a woman couldn’t have a credit card. When women were meant to be wives and mothers, and nothing else. This was a time when smoking, and drinking, and saying naughty words on stage was seen as very fun, and Vegas was the capital of naughtiness, and these guys created in their breaking each other’s acts up, and going on stage, and making all these drunk jokes, and these racial jokes about Sammy Davis, Jr. They were the naughtiest thing going, and the crowds in Vegas loved it, and the Rat Pack became a legend.

You look at it today, people feel different ways about it. I happen to think from my perspective many years later, that almost everything they did on stage doesn’t hold up very well. Unlike Sinatra’s singing, it doesn’t hold up. You had to be there. You had to be there at that time when everything naughty was fun. Everything that was naughty then, it’s not naughty anymore, and so the humor isn’t funny. The racial humor is kind of offensive, and, yet, the image of these guys in their tuxedos, with the ties loosened, on stage, looking so handsome, and acting so silly, and in such a stylish way, people, men and women, are very willing to overlook the silliness, the offensiveness of a lot of the material, overlook that, and really just look at the style instead. This is why the myth of the Rat Pack endures.

Brett McKay: Yeah. When you talked about some the jokes at Sammy Davis, Jr.’s expense, man, I felt that punched in the gut. I felt bad for the guy.

James Kaplan: Yeah. One of the very many people I interviewed for the second volume of my Sinatra biography was the great Quincy Jones, the African American musician and arranger, a brilliant, brilliant man, and he arranged the great Count Basie album, a Count Basie Sinatra album, and he conducted and arranged Sinatra’s famous shows at the Sands a few years after the Rat Pack shows in 1965, 1966. Sinatra used to stand up on the stage in the show room of the Sands, the Copa Room, and he would make these silly racial jokes. I asked Quincy Jones, “What did you think when you’re there on the podium conducting the great Count Basie Band, and then there’s Sinatra making these Amos and Andy jokes. What did you think?” Quincy Jones said, “I didn’t like very much,” and why should he have? They don’t sound very good today. I don’t like them very much either.

But, back then, back then, it was a different time and a different place, and I’m not saying those jokes were right, but the audiences then thought they were just hilarious, and, of course, they were white audiences.

Brett McKay: Right. That’s the other paradox about Sinatra though, is even though he would make these politically incorrect jokes at the expense of Sammy Davis, Jr., he was a really good friend to him. They had some falling outs, but he stuck out his neck. One time he stood as a best man at Sammy Davis’ wedding to the white model.

James Kaplan: When Sinatra was in his late teens, and just beginning to sing, and before anybody had a clue who Frank Sinatra was, he used to go to West 52nd Street in Manhattan. This was a block between 5th Avenue and 6th Avenue in Manhattan. Today, it’s all glass office towers. Back in those days, it was all brownstones, three story buildings, and in the basement of every building was a jazz club. You could walk down this block, and there were fifty jazz clubs, and in the basement of every one of these buildings, there was a great jazz club, and these geniuses. You could see Count Basie. You could see Duke Ellington. You could listen to Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, and Sinatra stopped in every one of those jazz clubs, and he idolized these. He knew great musicians, great musicianship when he heard it. He knew these African American artists were geniuses, and they carried themselves like royalty, and that’s how Sinatra regarded them.

As a liberal Democrat from the beginning of his life, and even though he switched to a more conservative political stance, Sinatra was always a passionate advocate of tolerance, and he walked the walk as much as he talked the talk, and even though he this disagreeable side to him, he had this paradox that he could make the silly racial jokes, he stood behind his feelings.

Brett McKay: Yeah. This is the Art of Manliness podcast. We got to ask this. Why is Sinatra still such a potent icon of American masculinity, even today, and what was it about him that … There’s that famous quote, women wanted him and men wanted to be him.

James Kaplan: Yeah.

Brett McKay: What’s going on there?

James Kaplan: I think you have to look deep underneath everything. Yes, we can look at the aura, the mystique, the style of the Rat Pack. I think that will go on for a long time. Young people love that. Young people love to think about it, drink the martinis, smoke the cigarettes, imagine how fun it would have been to be in the Rat Pack, but I think long after all that has faded, all that mystique from the ’60s has faded, what’s going to endure is Sinatra’s singing voice. This is a voice for the ages, for the centuries. I think that people will still be listening to Sinatra centuries from now, and why will they be listening? Because Sinatra, unlike … Listen, there are a lot of great voices, a lot of great voices, on record, and even today, many wonderful voices, but Sinatra had and still has in recording, this absolutely unique ability to make you feel that he was feeling these feelings, as in the instant that he was singing these songs. Nobody else can really do that.

It is an intensely, a definitely masculine voice, and it is a voice that is filled with … And this is the key to the whole thing, a completely acceptable … Frank made it acceptable, vulnerability. Frank created acceptability for vulnerability in a man. He was a guy who could sing a torch song, and really sell it, because you thought he was feeling it. He was really feeling it while he was singing it, and so it’s not just macho. It’s not just swagger. Frank had plenty of that, and he can swagger with the best of them, but it’s this vulnerability, and, again, this genius at conveying the feelings of these great songs that he sang, that make men feel that it’s okay to be vulnerable and make women feel this is a superbly masculine man, but this is a man who is not afraid of his feelings, and that, too women, of course, is a very, very sexy combination.

Brett McKay: James Kaplan, this has been a great conversation. Before we go, where can people find out more about your books?

James Kaplan: On my wonderful website, JamesKaplan.net. They can read everything about my two Sinatra biographies, my other books as well. Of course, both books are on Amazon. I really want to thank you, Brett. It’s very seldom that I get to speak for so long about this great artist, and about this music that I love, and it’s clear you have a lot of the same feelings for him, and so it’s terrific to talk with you.

Brett McKay: Thank you so much, James.

James Kaplan: Thank you, Brett.

Brett McKay: My guest was James Kaplan. He is the author of the book, Sinatra, the Chairman, and that’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. A really great read. You can find out more information about his work at JamesKaplan.com, and, like I said at the beginning of the show, if you want the show notes for this podcast, if you go to AOM.IS/Sinatra, you’ll find highlights, links to people, stories you mentioned, as well as a suggested Frank Sinatra playlist from James himself.

That wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at ArtofManliness.com, and if you enjoyed this podcast and have gotten something out of it, I’d really appreciate it if, one, you could tell your friends about it. Spread the word about the show, but, also, give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. That helps us out a lot.

As always, I appreciate your continued support, and, until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.